Referred to by some as “Thundersticks,” firearms were brought to the western hemisphere by European explorers and settlers. They quickly became incorporated into Native American life and from the 17th through the 19th centuries guns transformed life for Native Americans in a variety of ways and accounting for the rise and fall of many groups.

In this book, David Silverman seeks (and succeeds) to debunk the myth that the Native acquisition of arms accounted for their ultimate subjugation at the hands of Euro-American authority. In fact, that was overwhelmingly not the case, as he shows through displays of “Native economic power, business sense, and political savvy.”

The book progresses chronologically and geographically moving back and forth across the nation as it follows what Silverman calls the “gun frontier”— a place where Native groups fought rivals, seized control of various markets, and responded to expansionist powers. Each chapter focuses on a new gun frontier where Natives and Euro-Americans exchanged guns for a variety of furs and pelts, like sea otter in the Northwest and deerskin in the Southeast, as well as slaves. Although the body of the book remains focused primarily on the 17th – 19th centuries, the narrative continues to include contemporary Native use of guns, including the AIM (American Indian Movement) occupation of Wounded Knee in 1973.

|

| The image of a Thunderbird on top of a totem pole |

Silverman argues that American tribes developed political economies that would supply them with guns to be used against Euro-American powers, and, likewise, against other groups. Their “dependence” on guns did not prevent them from pursuing personal interests and defending their political and economic authority during the period covered in this book.

Indian groups had widespread success throughout these two centuries at building and maintaining large arsenals of firearms. If anything, Silverman offers that Natives had the upper hand in the inter-dependent gun trade relationship between them and Euro-Americans saying “Indian polities used commercial and military leverage to shape these relationships [of trade] to their advantage.” Dependence on guns did not mean political subservience to Euro-American governments.

So how were Indians able to keep their autonomy over the gun trade? During diplomatic negotiations it was common practice to receive gifts as a sign of brotherhood. While Anglo states remained unable to exploit Indian need for munitions to force them to cede land, they did use gift diplomacy to sway Native peoples towards or against one side during periods of conflict. Likewise, Indians used what many historians have come to call “play-off diplomacy” in the Southeast to seek favorable trade negotiations and gifts from the French, Spanish, and the English—who all had colonies or forts in the region that directly challenged Native claims.

To further keep Native trade interests satisfied and supplied, arms suppliers tailored their guns to the Indian market. The advantage in the arms trade came to suppliers who produced light, durable, smoothbore muskets with decorative elements, often depicting Native spiritual beings. For some Indians, these thundersticks were associated with the most fearsome of natural elements and embodied the awesome power of the Thunderbird and the Horned Underwater Serpent, revered Native spirits.

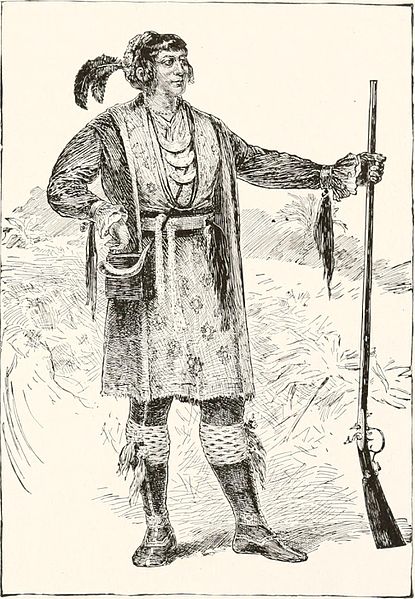

|

| Osceola, the Seminole, with a rifle |

Only recently have historians begun to write from the Native side, giving them increased agency in the formulation of their history. Silverman uses archaeological records to tally the staggering number of guns Natives possessed at their camps as well as the smithing tools used to repair and maintain their arms. But he also describes how their “growing self-sufficiency... spelled trouble for the English.” Silverman’s narrative insists on positioning Native Americans as the key players and influencers in this exchange.

The arrival of guns did create what we might call an Indians arms race that catapulted all indigenous groups into a new world of interactions with rival groups and European powers. The success of some Native groups in this new world did come at a price for others. Indian groups with less access to or unwilling to participate in the arms race were the first ones to be overpowered by their rivals or by Euro-American forces. The surrender of Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull represents the closing of the advancement of Native groups through the gun trade and an ominous start to a new chapter at the close of the nineteenth century.

Over the course of two centuries, guns re-shaped the indigenous world. Many Native groups embraced those changes. Guns were an essential feature in the colonial development of North America. But rather than assume that Indians plummeted into a state of death, land loss, and impoverishment at first contact with European forces, Silverman challenges that notion, providing 200 years of evidence across the nation of persistent and powerful Native groups.