At the turn of the 20th century, the concept of “blood” took a central role in determining Native American political status and personhood. Blood discourse can be added to the long list of assaults enacted on the Native American community, put alongside boarding schools, forbidden language and culture, land loss, and poverty. During the assimilation period (1887-1934), blood quantum served as an integral means by which white people became aware of Native American people.

It is curious, however, that “blood” terminology, like “half-blood” and “full blood” are not mentioned in the 1887 General Allotment Act, also referred as the Dawes Act, that provided the broad framework for the policy of assimilation. Only in 1934 did blood became a signifier in the official definition of Indian status through the Wheeler-Howard Act. Still, much is at stake in the language of blood. Blood was part a broader strategy of elimination, a tool used to efface Native American history, identity, and geography.

|

Katherine Ellinghaus is an Australian historian, familiar with Australian settler government legislation that contained blood-based terms of who was an “aborigine.” Her familiarity with the Australian context alerted her to the valences of this terminology in Native American assimilation policy and prompted her exploration into this topic. Few studies before hers have investigated the relationship between “blood” and policy in this period.

Three tropes of blood discourse existed during the assimilation period. With the first, those of mixed-descent (with one white parent) were considered smarter and more capable of life in the majoritarian society. The second trope carried the romanticized element of the pure, “noble savage,” and any non-Indian blood destabilized their authenticity as a Native American. that Indians with African American heritage constitute the third trope which Ellinghaus explores. These people suffered under existing prejudices and could have their Indian status nullified.

|

Ellinghaus examines these three tropes through multiple and diverse case studies which demonstrate the effects of blood discourse on government policy. Ellinghaus breaks this period up into three stages. In the first, before any “scientific” blood-based definitions existed, the U.S. government was already applying this discourse to artificially construct Native American groups. Stage 2 introduced a “competency” policy wherein those who were deemed “competent” were released from 25-year trust period on lands under the Dawes Act. This has devastating effects on Indian landholdings. The third stage defined “Indian” as belonging to one of three groups under the 1934 Indian Reorganization (Wheeler-Howard) Act. Blood was an immaterial measure of Indian status for those enrolled in a federally recognized nation; the others who were not "of one-half or more Indian blood" however, had a more tenuous path to becoming recognized as an Indian. Although the act, part of an "Indian New Deal" supposedly ending the assimilation period, continued the perception that mixed descent Indians could not receive tribal status or government protection.

The result, and perhaps the goal all along, was to use this blood classification of Indians to reduce the total number of them, and the number of those who could claim land and other Federal benefits. In the case of the Anishinaabeg of the White Earth Reservation in Minnesota, for example, Ellinghaus shows how Tribal membership was increasingly regulated by the U.S. government rather than the Anishinaabeg themselves once the allotment process began. The Dawes Commission declared as many of the Anishinaabeg as possible “mixed blood,” the enormous loss of land that resulted from this was dubbed the “White Earth Tragedy.”

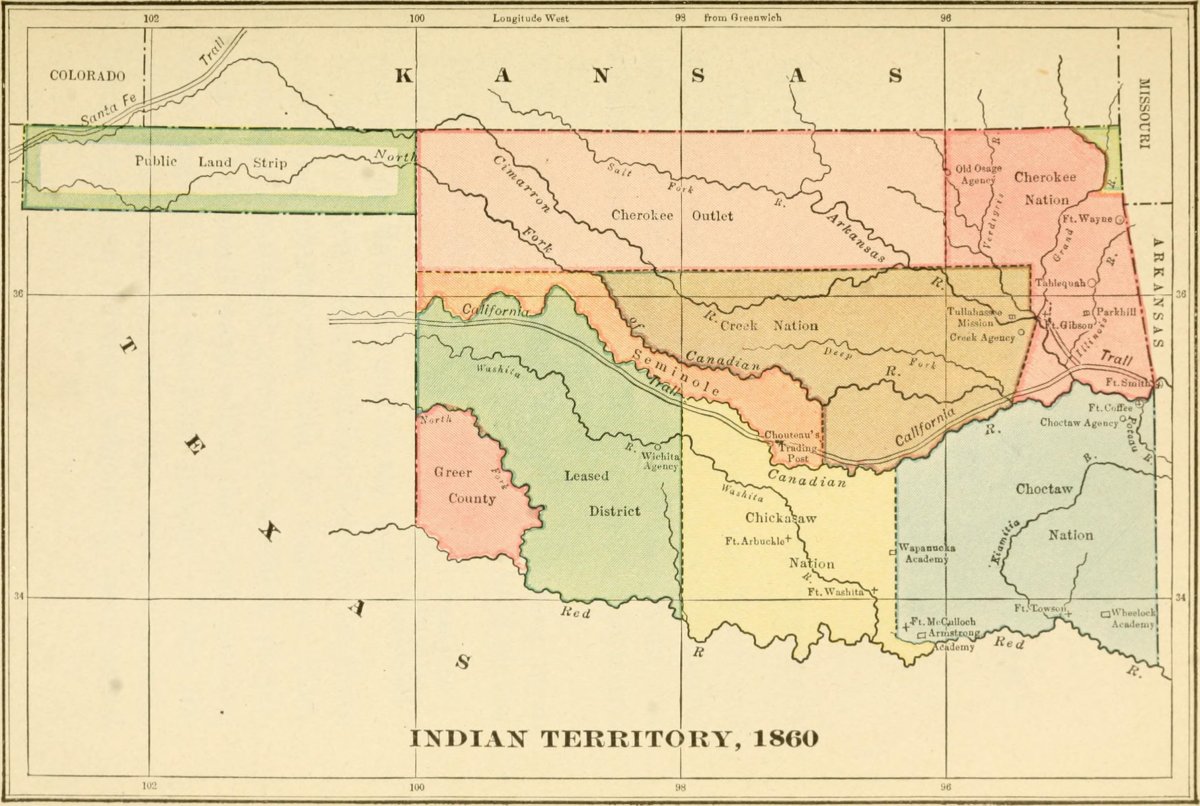

Similarly, when the Dawes Commission dealt with the Five Tribes of Oklahoma it assumed that there were three kinds of Indians. According to this typology, the commission believed that mixed white/Indians were taking advantage of the claim to indigeneity and were undeserving of the allotments that “full bloods” needed as “primitive and uneducated” victims. (27) Thus, any white ancestry was a factor that removed special privileges of indigeneity. This blood discourse reduced the number of Natives on tribal rolls who were entitled to land and benefits.

Blood discourse was also used as a solution for the “Indian problem.” Indians of mixed descent were said to be able to assimilate into society more easily than “full blooded” Indians, thereby negating the need for land or other resources that government promised Native Americans. In the early 20th century, the Office of Indian Affairs issued certificates of competency allowing individual Indians to sell, lease, or mortgage their land. Cato Sells, commissioner of Indian Affairs in 1913, emphasized competency as a means of solving the “Indian problem.” Releasing “white Indians” from governmental control was the beginning of the end of the problem. If fewer Native Americans were “on the books,” less money and administrative time could be spent on the seemingly unsolvable “Indian problem,” making it easier for their lands to be removed from their possession. This benign-sounding policy says Ellinghaus “was the catalyst for an enormous transferal of Native American land to non-Indians.”

Native Americans did not sit idly by while this happened to them. Resistance and refusal to adhere to the application of blood-based discourse policy cropped up throughout the assimilation period. The White Earth community and the Five Tribes of Oklahoma resisted through legal means. Many nations had their own laws for citizenship according to clan, kinship, and tribal law all of which existed before the Dawes Commission. Cherokee chief Oochalata wrote to President Grant in 1876 arguing that if their nation could not “define its own identity it can not determine its own destiny,” representing the underlying aspect of Indian agency and self-determination. (37)

Ellinghaus offers this book as a means for critiquing and analyzing the phenomenon of settler colonialism which allowed for tropes of authenticity to persist to today. It also adds to the story of Native Americans’ unrelenting resistance with racial science and white structures. In light of the semi-recent events at Standing Rock, Native American persistence throughout history is again highlighted by their ability to resist and act against their oppressors. Blood discourse is just one narrative that needs its recognition as central to indigenous history and Ellinghaus suggests that it should be handed back to Native American communities to decide who is an Indian and who isn’t.