Evolving patterns in global migration and changing U.S. laws have militarized the United States-Mexico border in recent years

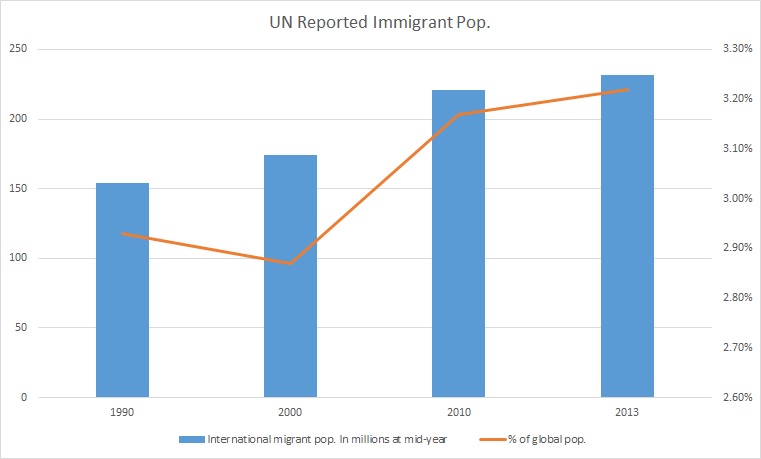

People all over the world are on the move. Some are seeking better economic opportunities; others are fleeing desperate circumstances in their country of origin. Either way, the United Nations classifies over 3% of the world's population as migrant—a staggering 230 million people. Of those, 11.5 million are living in the United States without authorization, most of them from Central and South America. This month historian Steven Hyland examines the current movement of people from south to north in the Americas—and the current U.S. debate over immigration. He reminds us that these processes are not only recent phenomena but are part of a much longer history of global migration to, within, and from Latin America.

Read and Listen to Origins for more on Latin America: Latin American Drug Trafficking; Rethinking Cuba Libre; Brazil’s Elections; Brazilian Politics; and Anti-Americanism in Latin America.

Read about U.S. Immigration Policy and Operation Wetback

This past summer the American public awoke to the spectacle of thousands of children from Central America, some as young as five, crossing into the United States without authorization. News accounts detailed these children’s treks: traveling on the tops of trains, sleeping in the open air, and navigating violent encounters with criminal gangs and corrupt officials.

The images of these children herded into detention centers in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas launched a public debate and stirred criticism of the Obama administration.

Responses to their arrival varied widely. Some towns, cities, and counties opened their doors and institutions while other jurisdictions declared these children unwelcome.

|

| A U.S. Border Patrol poster placed around the border with Mexico. It translates: "I thought that it would be easy for my son to get papers [e.g. legal status/work rights] in the North. It was not true. Our children are our future. Let’s protect them.” |

And those hoping for a dispassionate and sober discussion on immigration policy—what to do with the roughly 11.5 million people living here in the United States without authorization—have been disappointed.

Although the images of these children walking through the Americas are startling, they are part of a much older and more enduring story. Mass migration of humans across the globe is a signature feature of the modern world, and the Americas have long been at the forefront of these complex, worldwide dynamics.

The highly personal act of migration both in the past and today reveals much about the functioning of the world economy and how sending, receiving, and transit societies fit into it. As in the past, all regions of the world are involved in large-scale migration.

According to United Nations estimates today, 3.2% of the world’s population is migrant, defined as a person residing in a nation-state other than the one in which he or she was born. That percentage translates to a staggering 231 million people. Of this number, 15 million are classified as refugees, fleeing civil war and political unrest.

|

| A United Nations graph showing the immigrant population as a proportion of the total population |

A large share of current and past migrants found their way to the United States, long a destination for the adventurous, the fleeing, and slaves forcibly uprooted. Indeed, immigration is a key characteristic of how Americans view their national history and the evolution of U.S. society—an important part of the story of what it means to be an American.

Yet this story is not the sole province of the United States, and this nation’s experience is only one part of the larger global context. In the Americas, in addition to Canada, several Latin American nations have also received millions of immigrants from Africa, Asia, and Europe.

Immigration to these countries, especially Argentina, Brazil, and Cuba, transformed their societies, influenced their histories, and continues to shape understandings of their national identities. And the idea of Hacer América—the pursuit of one’s future and the achievement material wealth in the New World—has been, like the U.S. “American Dream,” tremendously important to the migration experience to Latin America in the era of mass migration.

The immigration of peoples from other continents to Latin America and the Caribbean began in the years after the arrival of Columbus in the 15th century. Most indigenous peoples were killed by colonizers or diseases, to be replaced by Europeans and large numbers of African slaves imported to the region.

In the past 200 years, population movement in Latin America has increased through three stages: 1) waves of immigration to Latin America, particularly from Europe but also Africa and Asia, 2) migration among and between different Latin American countries, and most recently 3) movement of people from Latin America to North America.

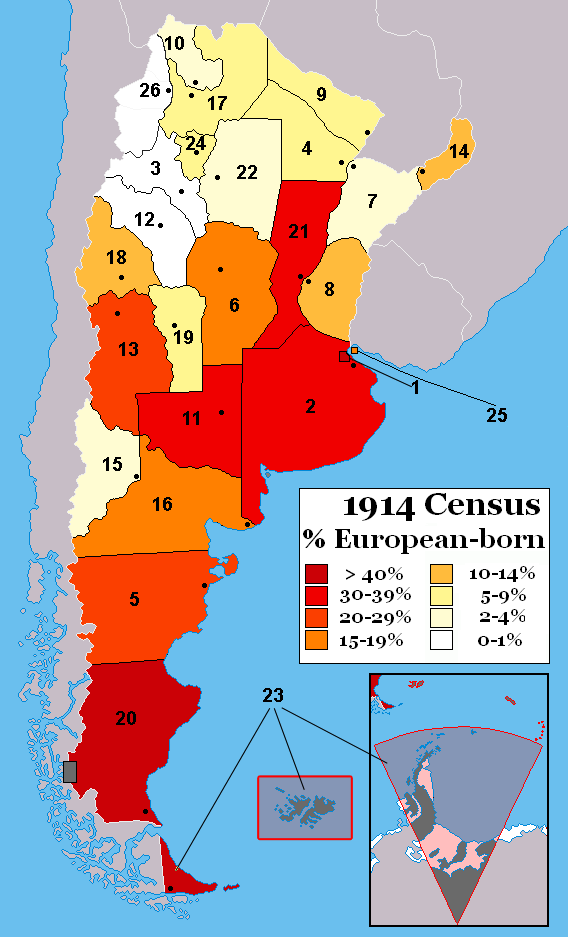

|

| A 1914 census of Argentina shows the effects of intense European immigration. |

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Latin America was a primary destination for international migrants from all over the world. With the dawning of the industrial age, a sequence of global economic processes and local forces combined to create the conditions for mass migration the world over and to shape its flows. Nation-states, in turn, crafted policies to encourage or discourage emigration and immigration.

In the wake of the global depression of the 1930s and the waning of international migration, internal migration and movement within the Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking Americas dominated population movement in the region.

In the years after World War II, the United States, which was in desperate need of labor, created programs to recruit workers from Mexico and the Caribbean.

Together, these postwar programs marked an important shift as Latin America transformed from a net importer of migrants to a net exporter. This exodus has only intensified in the first two decades of the 21st century, with the United States as the principal recipient of Latin American immigrants.

And while scholars, civil society groups, governments, and international NGOs study, fret, and argue about the movements of millions of people annually, migration in the Americas has a deep history that can help formulate sound policies at the local, national, and international levels.

The First Wave of Global Mass Migration

Over the past two centuries, a series of revolutions—demographic, agricultural, liberal, and industrial—originated in Europe, overlapped with one another, radiated out across the planet, and created the conditions for a global wave of migration.

From the early 19th to early 20th century alone, more than 50 million Europeans, Chinese, Japanese, and Arabic-speaking Ottomans migrated to the Americas. This flow was a significant increase from the estimated 3 million Europeans and 10 million trafficked and enslaved Africans that arrived between 1492 and 1820.

This huge movement of people began with a massive expansion of the world’s population that started in the middle of the 18th century, especially in Europe.

Advances in hygiene and medicine meant lower infant mortality rates and modestly extended life expectancy. Europe’s population surged from 140 million in 1750 to 429 million in 1900, accounting for 25% of the global population.

This population growth combined with transformations in land tenure, increasing productive capabilities, and a shift to commercial farming that meant fewer farmers could produce greater quantities of food. A byproduct of this so-called agricultural revolution was the displacement of the rural workforce, which became the first major source of migrants.

Liberal political and economic thought emerged as influential ideology in 19th-century politics. Emphasis on constitutional guarantees of individual liberties and free trade forced European and American rulers and leaders to accept emigration in practice and later in law.

As noted by the historian José Moya, liberalism transformed the idea of migration from “a matter of economic policy or social utility into a question of philosophical principle; of personal, inalienable rights.” Thus, over the nineteenth century, migration evolved into an acceptable life choice and ingrained cultural practice in a wide variety of global settings.

The industrial revolution—the mechanization of production accompanied by the creation of the factory system and emergence of a working class—also transformed patterns of human migration and movement. Industry benefited from the surplus labor let loose by population increase and commercial agriculture. Since many factories were located in cities, this marked the intensification of urbanization and rural to urban migration.

At the same time, the industrial revolution fostered new demands and desires by these wage laborers. New articles, such as factory-made shoes and clothing, watches, bicycles, and phonographs, found a market among the young and increasingly mobile. These workers craved consumer items and formed the bulk of emigrants to the new world in search of new economic opportunities.

Technological advances affected transportation too, although improvements were often designed to move products and not necessarily people. The spread of infrastructure—roads and railroads in particular—in the 19th century connected small villages with principal ports, moving ever more goods and persons to cities.

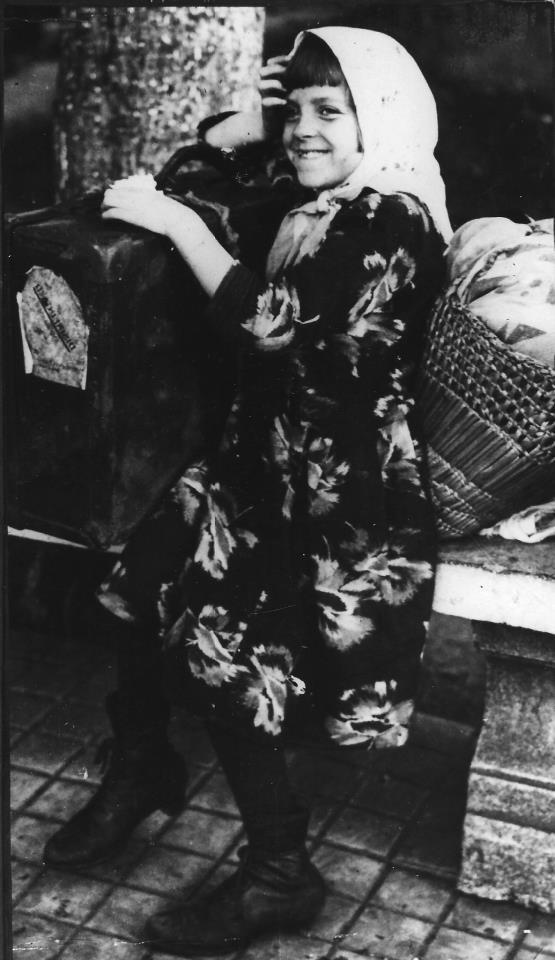

|

| Young immigrant girl in turn-of-the-century Buenos Aires; Credit: Wikimedia Commons/Archivo General de la Nación Argentina |

Increasingly in the second half of the 19th century, steamships replaced sailboats, dropping the travel time to cross distant seas while increasing the vessels’ cargo capacities. For instance, travel from northwestern Spain to Buenos Aires dropped from an average of 61 days in the 1860s to 26 days in the 1870s and decreased to ten days by the 1930s.

The result of these transformations was the first great wave of global migration.

More than 140 million people worldwide migrated to new countries between 1820 and the global depression of 1930, reshaping both sending and host societies in the process.

These revolutions happened unevenly across the globe and within continents themselves. Since these industrial changes happened in England first, it is logical that Britons comprised the bulk of European emigrants during the first two-thirds of the 19th century. Furthermore, the northern parts of Italy were more economically developed than its southern reaches and thus the initial wave of Italian emigrants came from the Piedmont, Liguria, and Tuscany.

As certain economies expanded, societies industrialized, and the opportunity to purchase property materialized, migrants selected particular countries in which to pursue their livelihoods.

The Americas proved to be a most attractive destination, receiving nearly 40% of all migrants worldwide before 1930 and 90% of European emigrants.

Large numbers of Italians, Germans, and later Spaniards and eastern Europeans flocked to the vibrant cities of New York, Boston, Buffalo, Cleveland, São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Buenos Aires and smaller hamlets sprinkled across the hemisphere.

Japanese settled along the Pacific coast of the U.S., in Peru, Bolivia, and Brazil. Chinese landed in Peru and Cuba, many as indentured servants.

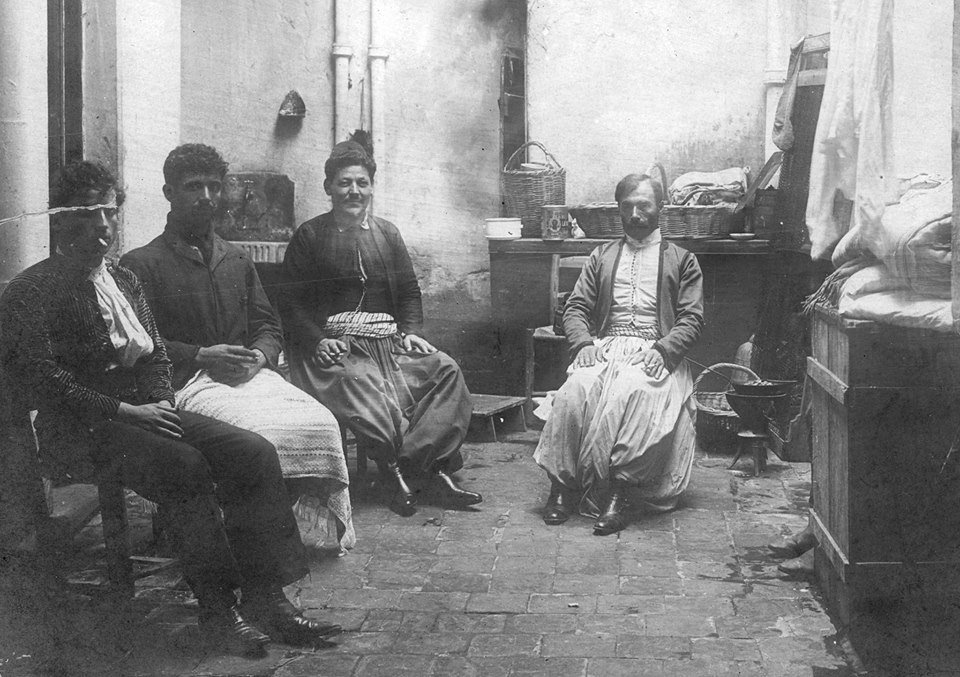

South Asians, also so-called coolie labor, moved to British colonies in Trinidad and Guyana. Syrians and Lebanese settled throughout the Americas.

In every sense, this was a world in motion.

The arrival of tens of millions of immigrants forced host nations to create new institutions and pass new regulations to encourage, manage, and sometimes stanch this flow.

The United States (1864) and Argentina (1876), the two most popular destinations in the Americas, passed legislation to stimulate immigration, such as subsidizing travel and arranging labor contracts prior to departure.

|

|

| The Statue of Liberty in New York welcomes immigrants the U.S.; This second statue in Rosario, Argentina is dedicated to the national immigrant population | |

Yet, despite state attempts to influence the shape and flow of migration, fewer than 2 percent of the more than 6 million immigrants to Argentina between 1840 and 1930 utilized subsidized fares. Rather, remittances and letters to family and friends became “a call and a gospel,” in the words of Italian politician Enrico Ferri, as the “mail stamp” emerged as the most important feature inspiring migration.

As migration intensified, however, different countries in the Americas began to target specific immigrant groups as undesirable and in some cases as threats to social well-being and state security.

Each nation passed laws and pronounced executive actions targeting groups of unwelcome immigrants, such as the United States’ Chinese Exclusion Act (1882), Argentina’s Law of Residence (1902) and the Law of Social Defense (1910) directed at anarchists and socialists, and Haiti’s anti-Syrian laws of 1903 and 1905.

Prior to World War I, the United States imposed a medical exam and a literacy exam for all desiring entry, especially for the eye disease trachoma. These exams pushed undesired immigrants to alternate destinations.

And in the 1920s, each nation passed laws and directives heavily restricting the number of immigrants permitted entry. The United States’ 1924 Immigration Act set a nationality-based quota system and an Argentine decree in 1923 demanded that would-be immigrants receive a consular stamp in the country of origin. In 1932, Argentina, in the midst of the Great Depression, required all potential immigrants to secure a labor contract before arrival.

Migration within Latin America since 1930

Historically, Latin America was an immigration region, receiving around 21 million immigrants from 1800 to 1970. Mass immigration into the region, however, had largely disappeared by the mid-1930s. In its place internal migration and movement within the region developed and intensified, especially to urban areas and (often seasonally or temporarily) to industrial and vibrant economic zones.

|

| Immigrant children on the grounds of the Immigrants Hotel in Buenos Aires, Argentina; Credit: Wikimedia Commons/Archivo General de la Nación Argentina |

After 1930, the impacts of the global depression combined with sustained population growth and state policies aimed at industrializing Latin American economies intensified rural-to-urban migration. This was, of course, a phenomenon seen throughout the developing world that continues today.

As a result, Mexico City grew from 471,000 in 1910 to 3.1 million in 1950 to 9.1 million in 1970 to 22 million in 2000. São Paulo grew from 200,000 in 1900 to 2 million in 1950 to 20 million by 2010.

The result of these processes was the concentration of Latin America’s populations in particular cities, the creation of poorly constructed slums, and the increased impoverishment of the countryside.

|

|

|

| Immigrants from the Ottoman Empire in Buenos Aires, Argentina, March 1902; Senegalese immigrants in Buenos Aires, destined for work in a sugar factory in the northwestern province of Tucumán, April 1899; Credit: Archivo General de la Nación Argentina | ||

Migration within Latin America, primarily laborers, increased as economic opportunities ebbed and flowed in particular locations due to specific economic conditions.

Seasonal Bolivian migrants increasingly traveled to northwestern Argentina to work the sugar harvest beginning in the late 1930s, culminating in a bilateral agreement in 1958. In addition, seasonal Paraguayan workers traveled to northeastern Argentina in the 1950s and seasonal Chilean workers to Patagonia in the 1960s.

|

| Two "castaways" from Syria, Buenos Aires, Argentina, August 1906; Credit: Archivo General de la Nación Argentina |

Suffering declining wages in the 1980s and desiring to avoid the rampant drug violence, Colombians moved en masse to Venezuela to work in the expanding oil industry, as well as agricultural and construction sectors. By 1995, 2 million people (almost 10 percent of the national population), mostly Colombians, were thought to be living illegally in Venezuela.

Concurrently, an economic downturn, growing political unrest, and Hugo Chavez’s attempted coup in 1992 contributed to significant outflow of Venezuelans, forcing the Canadians to reinstate visa requirements. It also led to threats of deportation against illegal aliens by Venezuelan authorities.

The rise of Latin American trade blocs, such as Mercosur and the Andean Group, has led to attempts to formalize treaties dealing with labor migration.

Over the past dozen years, 700,000 South Americans have emigrated officially to other countries within the continent, 500,000 in Argentina alone. The most populous groups of legal immigrants are Paraguayans and Bolivians.

Unauthorized migration within Latin America is significant.

Argentina is estimated to have an additional 350,000 illegal immigrants working in the shadows of the economy. In Buenos Aires, Korean immigrants own textile factories and hire illegal Paraguayan and Bolivian workers for 60-hour work weeks at $300 per month.

In fall 2014, Argentina decided to crack down on Colombians running afoul of the law by deporting them. Annually, 150,000 migrants cross into Mexico through its southern border without authorization.

In addition to these migratory flows, political violence and economic instability in Latin America also produced a large number of internally-displaced peoples (IDPs) and refugees, numbering 3 million and 635,000 respectively by 2012.

Due to drug violence, among other issues, nearly 10 percent of Colombia’s population is internally displaced. The return to democracy in Argentina in 1983 led to the repatriation of 10,000 of the estimated 60-80,000 political refugees. About 2 million Central Americans, however, were uprooted because of civil war in recent decades. Many ended up in the United States and have stayed.

Leaving Latin America: Immigration to the United States and the World

Latin America became a net exporter of people by the 1970s. This massive flow of illegal and legal immigrants from Latin America to the United States and Canada was set in motion by temporary labor recruitment, along with weak economies (including the devastation of high inflation in the 1980s), population explosion, civil wars, and political unrest.

While many of these issues were internal, external factors, such as U.S. policy and interventions, directly affected the shape and intensity of migration. This is particularly true with migration from Cuba, Central America, and the Dominican Republic.

Emigration from Latin America to the United States was originally based on temporary labor agreements, under which migrants moved back and forth for specific periods.

The Bracero Program, which operated from 1942 to 1964, permitted over 4.5 million Mexicans to work legally in the United States during the 22 years of the program.

|

| Mexican workers wait in Mexicali for legal employment in the U.S. as a part of the Bracero Program, 1954. |

The British West Indies’ complementary Temporary Foreign Worker Program ran from 1943 to 1977 and arranged for primarily Jamaicans, but also workers from Barbados and St. Lucia, to seasonally harvest apples in the U.S. northeast and sugar cane in south Florida.

These patterns of migration also combined with sustained poverty and massive population growth in the home countries. Simply put, many of the poorest Latin American nations in the post-World War II years produced many more people than their national economies could absorb.

In addition, emigration, as Princeton sociologist Douglas Massey points out, has become as much a cultural phenomenon as a socioeconomic necessity. Traveling to ‘El Norte’ to work is a rite of passage for many boys in the countryside, and increasingly for girls.

Though much of the migration within and outside of Latin America is voluntary (if irregular), human trafficking—both sex and forced labor—is a scourge that states in the Americas continue to battle with uneven policy measures, commitment, and interest.

The U.S. Department of State estimates roughly 16,000 people are trafficked annually into the United States. Latin American nations serve as both sources and transit points for slaves. An estimated 1,700 women from Latin America, primarily Colombians, Peruvians, and Brazilians, are trafficked each year to Japan. And Argentine police once discovered 700 Chinese trafficking victims destined for the United States.

Latin American Migration and U.S. Policies

In its current form, Latin American emigration disproportionately affects the United States.

There are an estimated 52 million people of Hispanic origin living in the United States, of which 33 million (64%) were born there and are thus citizens. Many of these families have been in the country for generations, especially in the American Southwest.

Nearly 19 million were born abroad. While many of these immigrants have legal right to remain, demographers estimate that 60% are here without authorization. The unauthorized immigrant population has more than tripled since 1990 from 3.5 million to 11.5 million, and the largest percentage increase has been in the Old South and the Mountain West states.

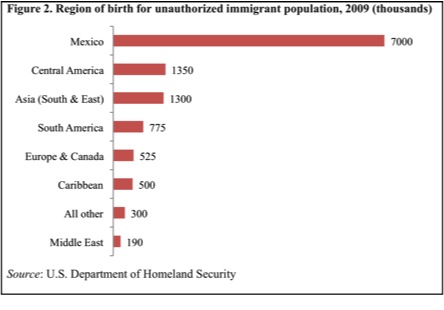

Latin America and the Caribbean account for nearly 80% of unauthorized residents in the United States, and Mexicans represent two-thirds of Latin Americans and half of all unauthorized migrants.

|

| With numbers in thousands, this graph represents the country of birth of unauthorized immigrants in the United States in 2009. |

The regulations that the United States has put in place over the years to manage immigration are important in defining the patterns and experiences of migration.

The 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act repealed the nationality-based quota system erected in the 1924, replacing it with a visa system targeting skilled labor and preference for family members. The latter component continues to be a central feature of contemporary immigration policy.

The three decades following the bill’s signing into to law witnessed the arrival of more than 18 million legal immigrants, equaling a threefold increase over the period between 1935 and 1965. From 1965 to 1990, an important shift emerged as Mexicans became the largest group of immigrants while the number of Europeans fell precipitously.

Yet, perhaps the most consequential law was 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act, signed into law by President Ronald Reagan.

|

| Pedestrian border crossing Tijuana, Baja California, Mexico. |

This law allowed unauthorized residents to apply for legal status, which they could gain provided they met a set of criteria such as not having a criminal record and having maintained continuous presence in the country since January 1, 1982. In return, they gave up access to public welfare programs for five years. This latter provision did not apply to Cubans and Haitians. Nevertheless, an intensification of Latin American immigration, especially from Mexico, started.

The 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act augmented resources for border security and announced penalties for employers of unauthorized immigrants. Section 287(g) of the 1996 law had been used to empower local law enforcement with certain abilities to enforce federal immigration law, in particular allowing a law enforcement officer to inquire about a person’s immigration status. The program was scaled back in December 2013 due to criticism that it promoted racial profiling.

Instead, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) has utilized the Secure Communities program which was piloted in 2008 and is operational all jurisdictions nationwide. This program, which does not allow law enforcement to ask about residency status, calls for an arrested person’s fingerprints to be run against a national residency database. This practice, too, has generated criticism by civil rights and immigration reform activists and the Obama administration announced in November 2014 that it would discontinue the program.

These combined programs, nevertheless, have led to the deportation of nearly 300,000 convicted criminal aliens and over 1 million total people in the U.S. without authorization since President Obama took office in January 2009. The overwhelming majority of those deported are Latin Americans.

One of the immediate political consequences of the number of migrants from Latin America has been the militarization of the U.S.-Mexico border.

More armed personnel and border patrol agents guard the frontier now than ever before, growing from 9,800 in 2001 to 21,394 in 2012. The government has erected physical barriers and enhanced surveillance equipment.

The perceived crisis about a decade ago also led to the rise of vigilante groups, such as the Minutemen, who took it upon themselves to watch the border. In response, migrants increasingly use so-called “coyotes” (guides) and thus pay more for traveling across the border.

The great irony of this militarization after the 1996 law is that it did little to stanch the flow of unauthorized immigrants. Rather, it led immigrants who successfully crossed to settle permanently in the United States. The new difficulties and dangers of crossing acted as a strong disincentive for circular or seasonal migration. In this sense, increased border security ended historical patterns of movement back and forth and created a disincentive for migrants ever to return.

|

| A photo of "Border Control at Sea" by U.S. Customs and Border Protection. |

Another political consequence is the polarization of activists largely into two camps, namely those that look at migration and family unification as a fundamental human right and those that emphasize the importance of the rule of law and the right of nations to secure their own borders.

According to one pernicious current of discourse, all Latin American immigrants are criminal by virtue of their unauthorized status. As political scientist Greg Weeks points out, being in the United States without authorization is a civil offense, not a criminal one; it’s more akin to a traffic ticket than arrest for assault.

When discussing the issue of immigration, it is worth distinguishing between people of Latin American origin born in the United States, those born abroad but with legal residence in the United States, and those here without authorization. In the discussion surrounding immigration reform, the term “Hispanic” is used to denote people from primarily Spanish American countries and also includes Brazilians and Haitians.

Obviously, this term as well as “Latino” flattens the diversity of these different Latin American and Caribbean immigrants and an Argentine living in Miami will likely view himself as having very little in common with a Salvadoran in Monroe, North Carolina or a Mexican in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Yet these catchall terms shape the contours of the debate.

Immigration and Economy in the Americas: What is Gained, What is Lost

Many critics assert unauthorized immigrants take from U.S. public services without paying into them.

Yet, nearly $1 trillion, most of which was contributed by unauthorized residents, has been deposited into the “Earnings Suspense File” of the Social Security Trust. By virtue of their status, they will never be able to claim these funds and thus, as the Center for American Progress (CAP), among others, points out, unauthorized immigrants have helped keep the Trust solvent.

|

| On May Day, 2006 - a march in downtown Los Angeles calling for illegal immigrants' amnesty |

In addition, all residents pay consumption taxes, whether at the grocery store, the movie theater, or the gas pump. Further, whether unauthorized immigrants rent or own they pay property taxes.

Opponents of illegal immigration argue that such people use medical services at hospitals, which by law have to serve all who arrive, without paying for it. Yet Greg Weeks observes in his 2010 book Irresistible Forces that these immigrants tend to be healthier and use the services less.

Finally, much rhetoric swirls about whether or not unauthorized Latin American immigrants take jobs from U.S. citizens. As commentators from comedian Stephen Colbert to Harvard economists have pointed out, the anecdotal and empirical data suggest that if any class of Americans is affected by the presence of illegal immigrants, it is high school dropouts.

More generally, these immigrant workers often help grow the economy. Economist Heidi Shierholz told the New York Times Magazine in 2013 that among her peers “there is a consensus that, on average, the incomes of families in this country are increased by a small, but clearly positive amount, because of immigration.”

In sum, much of the scholarly research demonstrates unauthorized immigrants pay taxes, use fewer services than presumed, and benefit the U.S. economy.

Similarly, there are important economic consequences for the sending countries, especially in the form of remittances. Immigrants remit billions of dollars to their families in their country of origin. While Mexicans return the most money, it is a small portion of that country’s massive economy.

Cash infusions from Salvadoran, Honduran, and Guatemalan emigrants, however, account for 16.5%, 15.7%, and 10% of their respective nations’ GDPs. This importance cannot be understated. Economists suggest that El Salvador’s poverty rate would spike sharply if remittances stopped.

While there is some concern in Latin American countries about “brain drain” to the United States, they do not discourage emigration for work in lesser skilled industries because the remittances are vital.

As a result, Latin American states have become proactive in engaging their diasporas by establishing mobile consulates that travel to areas with concentrations of their nationals and defending them to U.S. officials.

Latin American Immigration and the Future of U.S. Politics

Shortly after the November 2014 elections, President Obama announced a new executive action expanding deportation relief to parents residing without authorization in the U.S. whose children were born there. This decree built upon the DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals), which provided deportation relief for children and young adults who were brought to the United States without authorization by the parents.

The two programs permit the undocumented to receive a federal Employment Authorization Card and a social security number; the former must be renewed every two years. These documents enable many immigrants to secure a driver’s license in their states of residence. This has allowed many unauthorized immigrants to come out of the shadows and more fully integrate into local communities and labor markets.

Both programs provoked angry reactions from Republican politicians, who accused the president of ruling by fiat.

Immigration reform activists experienced mixed feelings because the new program was not as expansive as they had hoped. In one of its first actions of the new session, the Republican-led House of Representatives passed a bill containing language rolling back the president’s November program.

A fuller understanding of global processes that shape the conditions in which millions of people personally decide to migrate is vital for the crafting of a comprehensive and holistic set of policies both in the United States and in the sending countries.

|

| Students sit in on Senator John McCain's office to protest on behalf of the DREAM Act in May of 2010 |

For instance, the presidents of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras announced in November 2014 the creation of the “Alliance for Prosperity,” a program designed to transform emigration from an economic necessity to one of many options by investing in productive development, human capital development, citizen security, and strengthening of local institutions in their own countries.

An initial estimate of the program’s cost was $15 billion, most of which would need to be provided by foreign donors. Given the impoverished nature of these countries and the inability to effectively collect taxes, it is unclear how the plan will be implemented without outside donors.

Nevertheless, investing in people and institutions to develop local economies is vital to stemming the flow of emigrants in the middle and long terms.

In the United States, history suggests that immigration policies must reflect two basic elements, namely the reality of labor markets and the reality of the millions of immigrants residing in the country without authorization.

Migrants look at laws as simply one consideration of many when deciding to move. Yet a robust and sensible set of policies, such as a clearinghouse in which firms in need of lesser skilled labor can be matched with those desiring employment, is a first step to regularize labor migration that is otherwise contingent upon demographics, wages, and labor demand and less so on current immigration laws.

Secondly, laws utilized by the United States a century ago and with IRCA in 1986 provide a guidepost for the current phenomenon. Allowing unauthorized residents the opportunity to come out of the shadows and petition for legal residence (and not necessarily citizenship) provided they meet a set of criteria, such as demonstrating the payment of taxes and good behavior (e.g. no arrests), will strengthen communities and the economy.

Thus, combining programs in the sending and receiving countries is a necessary step to better allow nation-states to navigate the larger global forces that impel their citizens to migrate. Without these approaches, punitive laws will not dissuade people from entering without authorization.

The Americas have long featured prominently in global immigration processes, initially serving as primary destinations for migrants. Over the course of the twentieth century, Latin America transformed to an exporter of people, disproportionately affecting the U.S.

If the history of mass migration teaches us anything, it is that migrants will find a way to seek out new opportunities, and laws largely will not affect the flow of people so much as influence how these migrants integrate in local societies once they arrive at their destination.

Azpuru, Dinorah, and Violeta Hernández. “Migration in Central America: Magnitude, Causes, and Proposed Solutions.” KAS International Reports 2-3 (2015): 72-95.

Borjas, George J. “The Labor Demand Curve is Downward Sloping: Reexamining the Impact of Immigration on the Labor Market.” Quarterly Review of Economics 118, 4(2003): 1335-1374.

Castles, Stephen and Mark J. Miller. The Age of Migration: International Population Movements in the Modern World . New York: The Guilford Press, 2003.

Davidson, Adam. “Do Immigrants Actually Hurt the U.S. Economy?” The New York Times Magazine , February 12, 2013.

Fernández, Lilia. Brown in the Big City: Mexicans and Puerto Ricans in Postwar Chicago. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012.

Gabaccia, Donna. Foreign Relations: American Immigration in Global Perspective. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012.

Khater, Akram Fuoad. Inventing Home: Emigration, Gender, and the Middle Class in Lebanon, 1870-1920. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001.

Kugler, Adriana, Robert Lynch, and Patrick Oakford. “Improving Lives, Strengthening Finances: The Benefits of Immigration Reform to Social Security.” June 14, 2013. https://cdn.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/SocialSecurityImmigration-2.pdf

Lesser, Jeffrey. Immigration, Ethnicity, and National Identity in Brazil, 1808 to the Present. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Manning, Patrick. Migration in World History. New York: Routledge, 2005.

Massey, Douglas S., Jorge Durand, and Nolan J. Malone. Beyond Smoke and Mirrors: Mexican Immigration in an Era of Economic Integration . New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2002.

McKeown, Adam. Melancholy Order: Asian Migration and teh Globalization of Borders. New York: Columbia University Press, 2011.

Moya, José C. Cousins and Strangers: Spanish Immigrants in Buenos Aires, 1850-1930. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.

Ngai, Mae M. and Jon Gjerde, editors. Major Problems in American Immigration History: Documents and Essays . Boston: Wadsworth, 2013.

Weeks, Gregory B. and John R. Weeks. Irresistible Forces: Latin American Migration to the United States and Its Effects on the South . Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 2010.

Suggested Online Resources

Center for Comparative Immigration Studies (housed at the University of California, San Diego)

Immigration Resources from PBS Frontline

International Organization of Migration

Pew Research Center – Hispanic Trends

U.S. Customs and Border Patrol

U.S. Immigration Legislation Online (hosted at University of Washington, Bothell and Cascadia College)

U.S. Immigration Before 1965 (www.history.com)

U.S. Immigration Since 1965 (www.history.com)

U.S. Office of Refugee Resettlement – Unaccompanied Children’s Services