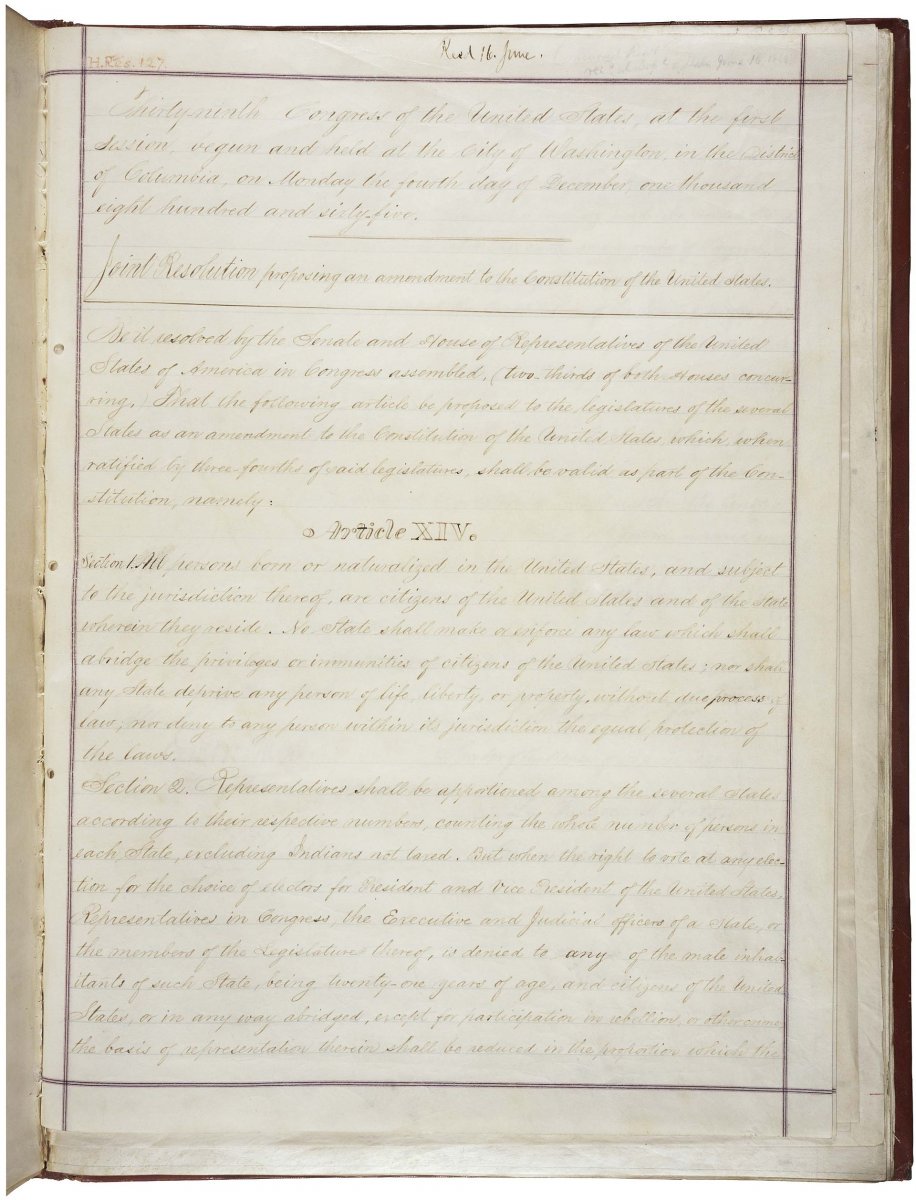

On July 9, 1868, the last of the 28 states needed to approve the Fourteenth Amendment acted, and Secretary of State William Henry Seward formally announced the ratification on July 28. It was a momentous event, a change to our constitutional system so fundamental that historians have put it on a par with the ratification of the original Constitution itself. In many ways, it gave Americans a new constitution.

On the most basic level, the Fourteenth Amendment set the terms for the restoration of the Union of the states after the Civil War.

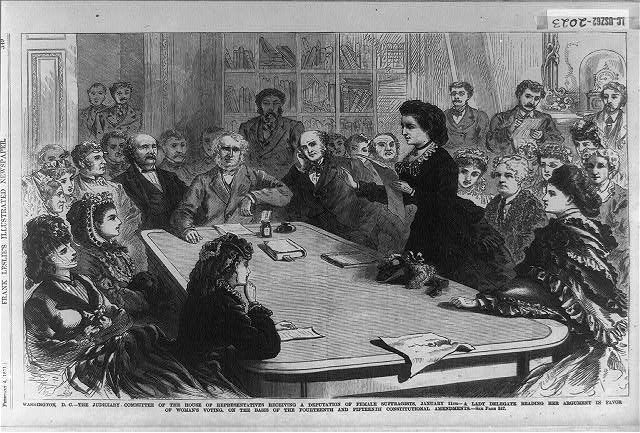

The second section revised the way representation in Congress was apportioned, aligning representation more closely with the voting population. Unless that was changed, southerners would gain representation in Congress (and therefore the Electoral College) by virtue of the emancipation of their slaves they had so strongly resisted, even though they did not allow African Americans to vote or hold office.

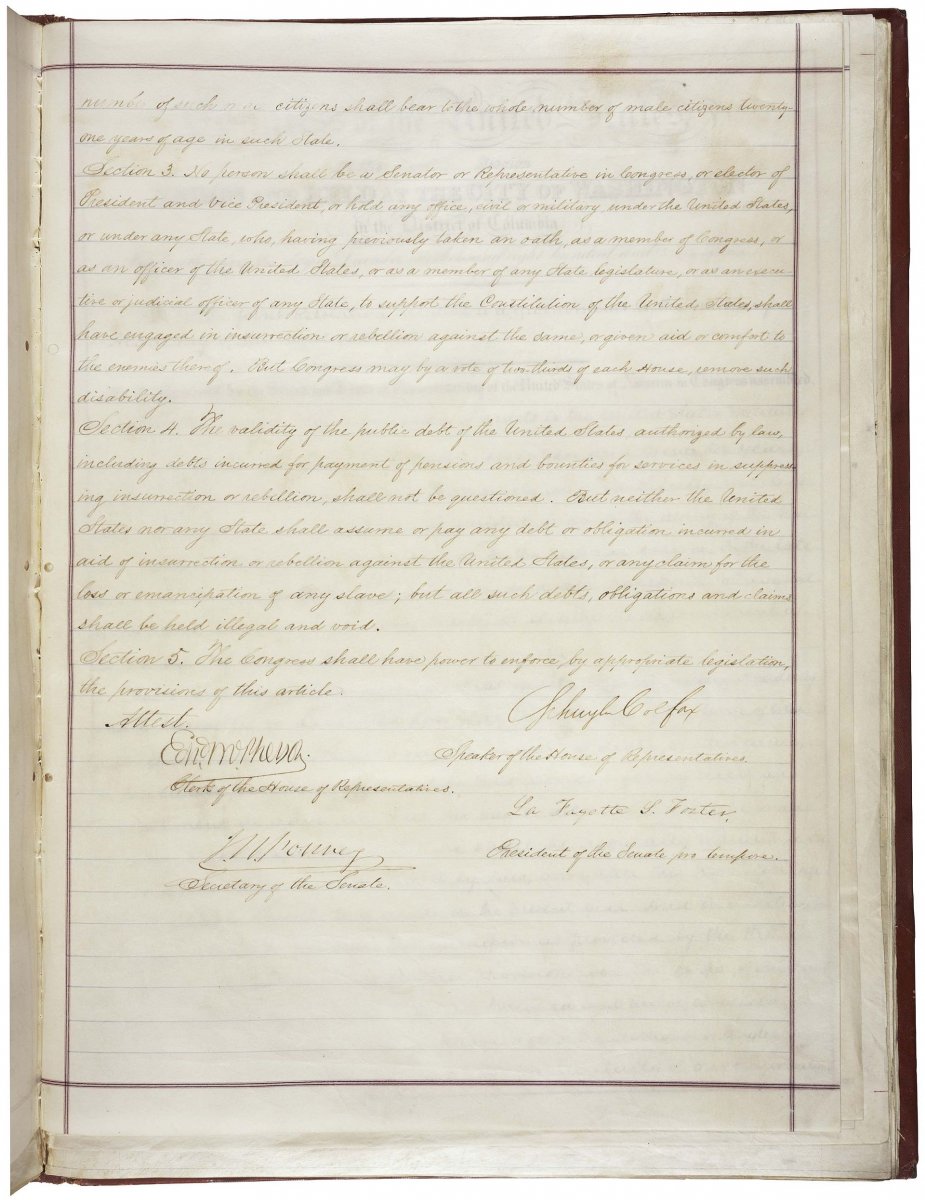

The third section disqualified anyone who had previously taken an oath to support the Constitution but then had joined the rebellion from holding state or federal office. The disqualification could be removed only by a two-thirds vote of Congress. The fourth section forbade payment of any of the debts Confederates had incurred during the insurrection. The fifth section empowered Congress to enforce the other sections by appropriate legislation.

But by far the most important was the first section. That section carried forward the implications of the Thirteenth Amendment that had abolished slavery. It declared all persons born in the United States and subject to its jurisdiction to be citizens of the United States and the states where they resided. And it barred states from abridging the rights of citizens; depriving any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law; or denying any person the equal protection of the laws.

The first section of the Fourteenth Amendment revolutionized the constitutional system in three ways.

First, it made citizens of everyone born in the United States, except Indians subject to tribal rather than U.S. authority. (Congress did not make all Indians citizens until 1924.) This provision swept away the state laws and judicial decisions that had limited citizenship to white persons, as well as the Supreme Court’s famous Dred Scott decision, which had applied the same rule to United States citizenship.

|  |

Second, the Amendment for the first time set general national standards that the states had to meet when establishing and enforcing state laws. Third, the Fourteenth Amendment was phrased in a way that enabled state and federal courts to intervene when its provisions were violated.

Over time, this third change has proved particularly important for our system.

|  |

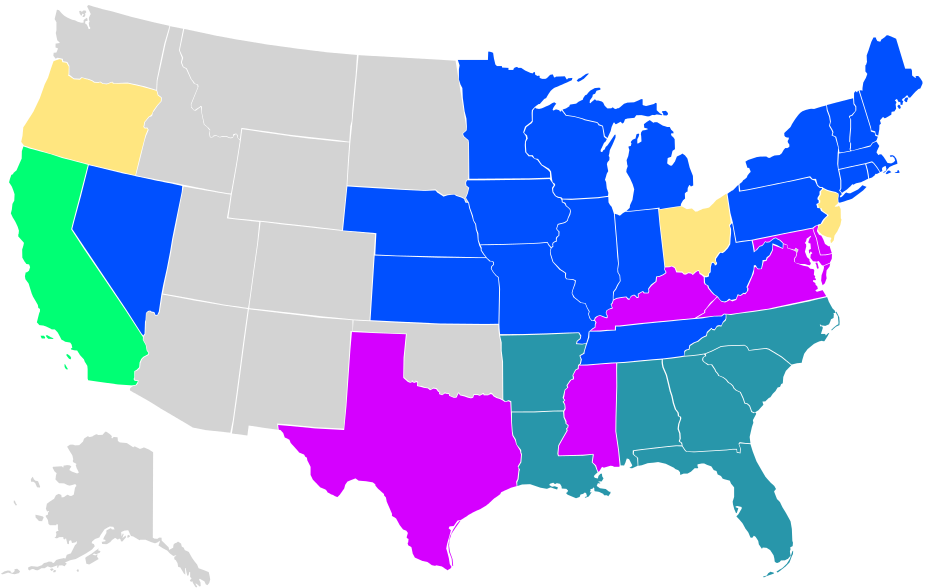

A map showing states that ratified the Fourteenth Amendment, and when.

Before the Civil War, state and federal courts were quite reluctant to rule laws unconstitutional. They were especially reluctant to do so to protect individuals and minority groups from hostile majorities. The Supreme Court had said it would intervene directly against state laws only when they violated expressly stated constitutional prohibitions. That meant that the provisions of the Bill of Rights, the main listing of Americans’ civil and procedural rights, did not apply against the states.

By stating explicitly that “no State shall” abridge the rights of citizens, deny due process, or deprive persons of equal protection of the law, the Fourteenth Amendment met the Supreme Court’s requirement. Moreover, it mandated that courts intervene to protect very vaguely defined rights. What constitutes due process? When does a state law or action deny equal protection? Inevitably, judges would have to decide what the concepts meant. Furthermore, these were rights of individuals to due process and minority groups to equal protection that the courts had never shown much interest in safeguarding.

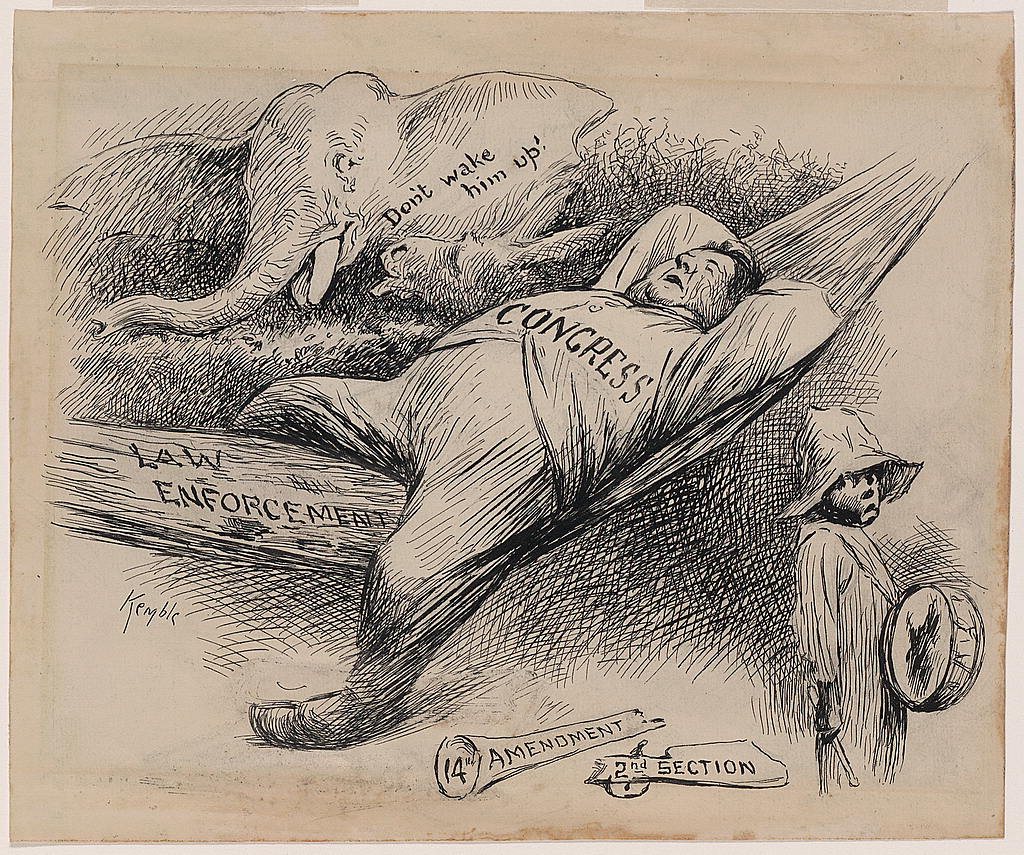

A fourth change could have been even more momentous. The fifth section, which empowered Congress to enforce the Amendment by appropriate legislation, applied to the first section as well as the others. There is evidence that the framers of the Amendment intended Congress to be as active, or even more active, than the courts in protecting individual and minority rights.

But that did not come to pass. The “no state shall” language was ideally suited to court rather than congressional enforcement.

The Supreme Court reinforced this fact by ruling that the Amendment gave Congress power only to counteract state action. It did not delegate power to counteract private denial of rights. The “state-action doctrine” has constrained congressional authority to protect rights ever since. It has been easier to argue that denial of rights inhibits interstate commerce than to rely on the Fourteenth Amendment.

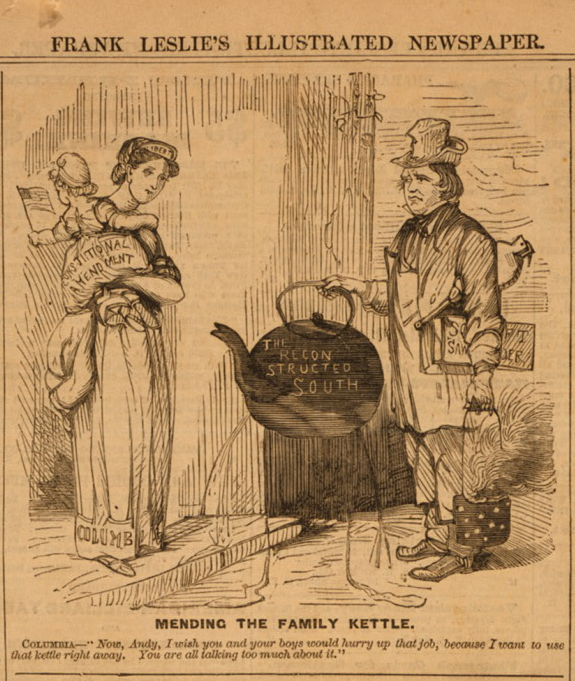

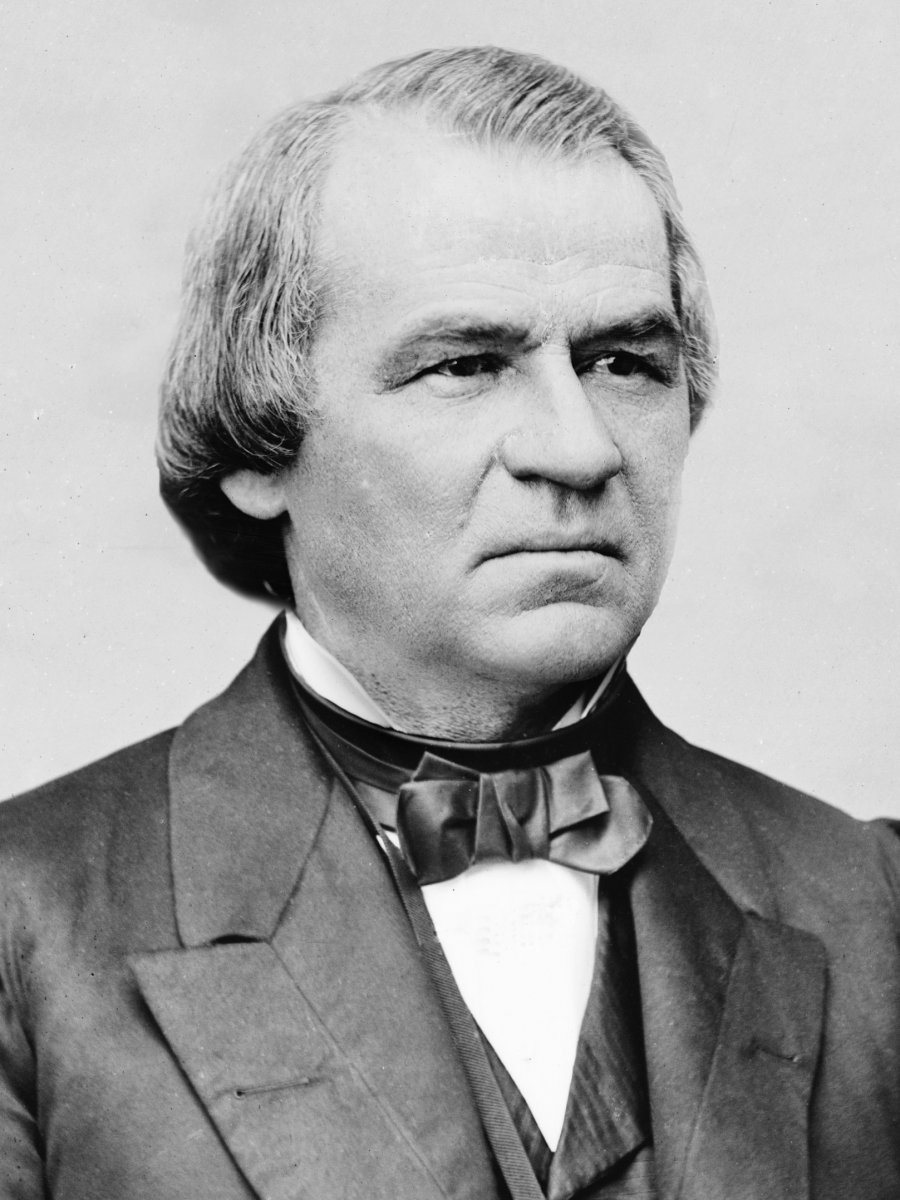

The proposed Fourteenth Amendment was very controversial. President Andrew Johnson, the Tennessee loyalist who succeeded Abraham Lincoln as president, fought it tooth and nail as did Northern Democrats.

|  |

President Andrew Johnson (left), and a message he sent to Congress in June 1866, voicing his displeasure with the Fourteenth Amendment as it was being sent to the states for ratification (right) (Library of Congress).

White southerners resisted almost unanimously. Only after northern voters backed Republicans overwhelmingly in the 1866 congressional elections and after Republican congressmen made ratification a condition for the restoration of any southern state, did they acquiesce.

For a long time, judges remained reluctant to undertake their new role. They distinguished between the broad rights associated with state citizenship and the limited rights associated with federal citizenship, saying the Amendment protected only the latter. They said that “due process” did not require observing any of the rights specified in the Bill of Rights. They ruled that reasonable discriminations based on race did not deprive anyone of equal protection of the laws.

But that slowly changed. Business people demanded judicial protection from laws and government actions that infringed on property rights. The courts began protecting property rights as early as the 1880s and 1890s. Black Americans and their sympathizers demanded that the courts protect equal rights. When state and federal laws suppressed criticism of the government during World War I, progressive lawyers and others formed civil liberties organizations to demand freedom of speech and the press.

Civil libertarians called on the courts to protect people from the excesses of the Red Scare of 1919 and the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s. The courts began to look to the Fourteenth Amendment to find the protections for due process and equal rights they now wanted to enforce.

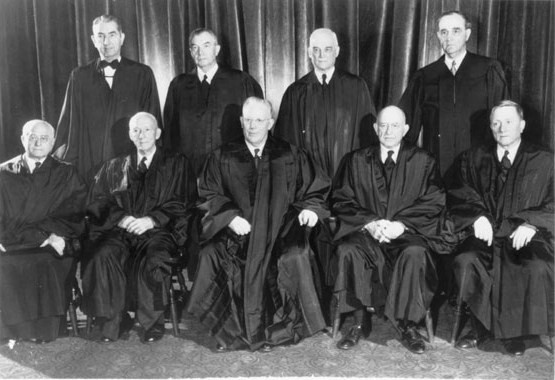

Slowly, they interpreted the Fourteenth Amendment to impose on the states most of the rights listed in the Bill of Rights. With Brown v. Board of Education, the 1954 decision ruling government-required school segregation unconstitutional, the Supreme Court began to overturn all government-sponsored racial discrimination. In the seventy-plus years since, state and federal courts have extended the principle to age and gender discrimination, aided by supportive state and federal legislation.

By the late twentieth century Americans accorded the courts, and especially the United States Supreme Court, a special, primary role in the protection of civil rights and equality before the law. We now consider such judicial review of government action a central part of the American constitutional system.

It has proven influential around the world—so much so that giving courts this central responsibility is often considered an essential element of any constitutional system that respects the rule of law. Perhaps the world would have reached that conclusion without the American example. But it would not have had that example without the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment.