Philippine naval vessel, BRP Mangyan, and crew.

On July 7, 2015 President Barack Obama hosted Nguyen Phu Trong, leader of the Vietnamese Communist Party, at the White House. This historic meeting was part of Obama's "pivot to Asia," a strategy to counter growing Chinese influence by engaging more deeply with other Asian nations. Nowhere is the tension with China felt more keenly than in the Philippines, the Asian nation with which the United States has a long and complicated relationship. This month historian Gregory Kupsky examines a century of Philippine attempts to define its nationality while facing often hostile and more powerful neighbors.

Read more on Asia from Origins: The China Dream; China and Africa; Remembering Tiananmen; Hong Kong; Taiwan’s Politics; Japanese Nuclear Power; and North Korea.

In early 2013 I took a tour of Corregidor Island, at the mouth of Manila Bay. Our guide ushered us through the military ruins left over from the “American Period” of Philippine history. After touting the close relationship between our countries, the guide referred back to the Spaniards who had first fortified Corregidor centuries earlier.

I noted that the island did indeed provide a strategic vantage point over the entrance to the South China Sea. The conversation paused. “Sir,” he said politely, “I believe you are referring to the West Philippine Sea.”

About a year later, President Barack Obama visited Manila to mark the signing of a new Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement. He and Philippine President Benigno Aquino III hailed their countries’ 63-year-old alliance and framed the deal in terms of military training and humanitarian assistance.

They also emphasized what it would not do: it would not reopen American bases in the Philippines, nor was the intent to “contain China.” This statement came in response to questions about a mounting dispute with Beijing over islands to the west of the Philippines. While not explicitly backing Manila, Obama stressed his commitment to preserving stability in the South China Sea.

Somewhere, I assume, my tour guide cringed.

For the Philippines, the current territorial dispute with China is only the latest episode in a turbulent history defined largely by geography. Situated at the confluence of major trade routes, the archipelago has witnessed a long progression of confrontations, from Spanish and Muslim incursions in the fifteenth century to the Pacific theater of World War II.

Filipinos have long found themselves transformed by the external influences of China, Japan, and the United States. And Philippine nationalism has often struggled to assert itself against such international pressures and powers.

|

| Map of Southeast Asia, with the Philippines at center. |

The Philippines’ relationship with the United States, the former colonizer that retains a strong presence, has been particularly complex. Historically Philippine leaders have resented American meddling in their affairs.

But, especially in recent years, they worry more about other, potentially worse, perceived threats, especially from neighbors closer geographically—as events in the South China (or West Philippine) Sea make clear.

The “American Period” (1898-1941)

Following their arrival in 1565, the Spanish quickly integrated the Philippines into their global network of trade. It was here that galleons unloaded Mexican silver and exchanged it for goods from China and Southeast Asia. In the process, the Spanish relied heavily on the services of Chinese brokers.

Numbering around 20,000 when the Spanish arrived, the Chinese in the Philippines had introduced rice as a staple, constructed the famous terraces of northern Luzon, and positioned themselves as a dominant merchant class.

By the late nineteenth century, however, there was evidence of growing resentment of both groups by the indigenous population. Calls for political separation from Spain began to grow alongside a movement to reclaim trades and industries from the Chinese.

In the decades leading up to its annexation of the Philippines, the United States was nowhere to be seen. Nineteenth-century Washington mostly maintained an unassuming role in the western Pacific, unable to compete with European power or Russian and Japanese proximity.

Even after Japan—forced by the U.S. Navy into the international arena in the 1850s—began to aspire to regional power, Washington welcomed the change, as a modernizing Japan could stabilize a region in which it had a natural interest. History, as we know, layers itself in ironies.

The American position in the Pacific changed fundamentally with the Spanish-American War in 1898. In May of that year, Commodore George Dewey crushed the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay and American troops occupied the city proper. Filipino revolutionaries proclaimed an independent republic, but it quickly became apparent that the United States would not be leaving.

Fighting erupted between the revolutionary and American forces in February 1899. It lasted three years, killing 6,000 Americans and some 200,000 Filipinos before the revolutionary movement conceded. In the Muslim-dominated southern islands, violence continued for another decade.

The American presidential election in 1900 became a referendum on annexation and, by extension, a more assertive American presence in the Far East. William McKinley and the annexationists won the election, and the Philippines became an American territory. Tariff walls went up around the islands, in marked contrast to Washington’s Open Door Policy in China.

In the four decades of the “American Period,” the new administrators built a government, school system, and infrastructure in their own image. They generally won the acceptance of the populace, though talk of independence persisted in Philippine political discourse.

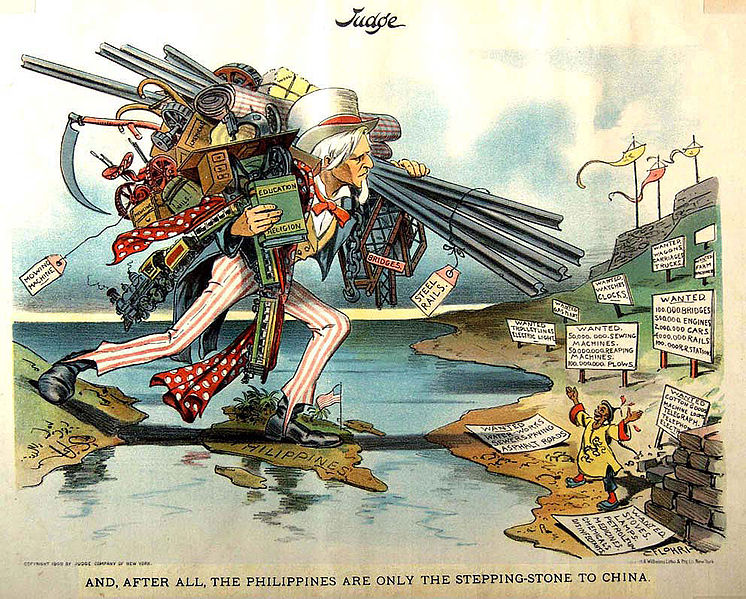

|

| An 1899 Judge cartoon on the larger implications of annexation. |

Geopolitically, annexation gave the United States a territory in the region and provided a springboard to Asia. In 1899, when the Boxer Rebellion in China targeted Westerners, 2,500 U.S. soldiers quickly traversed the South China Sea to help suppress the rebels. Similarly, in 1918 an abortive American intervention in the Russian Civil War was staged from Manila.

Philippine bases thus facilitated the projection of American power, portending what was to follow in 1945.

The Japanese Threat

The timeline of American ambition in the western Pacific coincided roughly with that of Japan, perhaps making a fight over the Philippines inevitable.

To expansionists in Tokyo, the Philippines seemed a colony underutilized by the United States. Meanwhile, economic opportunities drew growing numbers of Japanese migrants southward to Davao, on the island of Mindanao. So rapid was this growth that the Filipino nationalist press, which had long scapegoated the Chinese, shifted its ire to Japan in the 1920s and 1930s.

Pushing into Formosa (Taiwan), Korea, and eventually China, Japan made a bid for regional leadership, sometimes comparing its position to that of the United States in the Caribbean. American policymakers such as Theodore Roosevelt were unimpressed by such an argument. In fact, they began to rethink the level of deference that Washington had hitherto shown Japan in the Far East.

As Japan grew more aggressive, even some American imperialists began to see the Philippines as a liability. In 1907 Theodore Roosevelt pondered whether the islands formed a “heel of Achilles.” After World War I, American planners assumed the loss of the archipelago in the event of a conflict with Japan.

Such fears coincided with a renewed push for Philippine sovereignty on both sides of the Pacific. After much political jockeying in Manila and Washington, the Tydings-McDuffie Act of 1934 promised independence in 1946 and created a Commonwealth in the interim.

The new government received Major General Douglas MacArthur as military adviser in 1935. He remained following his retirement from the U.S. Army in 1937, striving in vain to acquire the resources for a national defense system. In July 1941, Washington recalled MacArthur to active duty, gave him a third star, and placed him in command of U.S. Army forces in the Far East. He spent the next several months in a desperate effort to reinforce the islands’ defenses.

Japanese raids caught MacArthur’s forces flatfooted at Clark Air Base within ten hours of the attack on Pearl Harbor. Two weeks later the Japanese invaded northern Luzon, and by New Year’s Day 1942 the Fil-American troops were holed up on the Bataan peninsula.

The defenders held out longer than expected in the face of disease, dwindling supplies, and the Japanese onslaught. They finally surrendered on April 9, 1942, placing 70,000 prisoners in Japanese hands.

The headquarters on Corregidor followed on May 6. It would be twenty-nine months before conventional Allied ground forces returned to the Philippines.

|

| The surrender of Fil-American troops on Bataan in April 1942 was the largest in U.S. history. |

Washington was forced to yield to Japan in the short term, subordinating the Pacific campaign to larger global aspirations, as best encapsulated by the “Europe First” strategy.

To Filipinos who had accepted American rule and resisted the Japanese invasion, the calculation was difficult to accept. Manuel Quezon, president of the Philippine Commonwealth, could not restrain his anger: “How typical of America to writhe in anguish at the fate of a distant cousin, Europe, while a daughter, the Philippines, is being raped in the back room!”

Having been ordered to Australia in early 1942, General MacArthur was nearly single-minded in his determination to avenge his defeat, however.

While awaiting his return, Filipino guerrillas—of the sort that had battled MacArthur’s father at the turn of the century—now fought alongside Americans who had evaded capture. They smuggled aid to prisoners of war, ambushed Japanese patrols, and transmitted intelligence to MacArthur’s command.

As a result, when the U.S. Army and Navy returned in October 1944, they were well informed on the strength and location of the Japanese defenders.

It is a testament to the geographical importance of the Philippines that Japan poured precious resources into its defense.

Offshore from the American landings on Leyte, the largest naval battle in history took place in a failed attempt to cut off the beachheads. The Philippines was also the birthplace of kamikaze attacks, and the Japanese employed the costly, to-the-death tactics that would characterize the rest of their war effort.

The outcome was virtually assured, however. Manila returned to American control in February 1945—albeit with horrific civilian losses —and the Japanese defenders were driven into the mountains, where they remained until the end of the war. General MacArthur presided over the restoration of the Commonwealth government on February 27.

Cold War Pragmatism: Between the U.S., Soviet Union, and China

On July 4, 1946, the United States delivered on the promise of independence, but as the Cold War came into full swing there was no question about whose sphere claimed the Philippines.

One of the first milestones of Fil-American relations was an $800 million aid package, predicated on the acceptance of a trade agreement that heavily favored U.S. economic interests in the country. The deal enshrined the “parity” rule, by which Americans enjoyed the same property ownership rights as Filipinos.

In March 1947, the two nations signed the Military Bases Agreement, granting the U.S. long-term leases on twenty-three installations, most importantly Clark Air Base and Subic Naval Base. The treaty also stipulated that American servicemen accused of crimes would be tried in U.S. military courts.

Four years later, a Mutual Defense Treaty obligated each country to aid the other in case of attack. In 1954, Manila hosted the meetings that created the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO), the Pacific analog to NATO.

While official relations were thus strong between the two allies, there was plenty in these agreements to provoke nationalistic resentment among Filipinos.

If the turn-of-the-century Philippines had provided a waystation for U.S. activity in Asia, now the archipelago became a keystone of a global foreign policy.

A permanent American presence served as a counterweight to the Soviet Union and Communist China. The American bases, especially Clark and Subic, were major support hubs in both the Korea and Vietnam conflicts. They supported various other types of intervention, from shows of force off Taiwan to the failed 1980 attempt to rescue American hostages in Iran.

|

| Aerial view of U.S. warships in Subic Bay, 1950s. |

In exchange for hosting the bases, Manila gained a powerful ally in maintaining domestic stability. The primary threat to that stability was the Hukbalahap (or “Huks”), an alliance of leftist, agrarian revolutionaries formed in 1942 to resist the Japanese.

During the war the Huks often collaborated with American-led guerrillas, but their Maoist leanings and opposition to U.S.-backed leaders led to considerable friction, at times inducing bloodshed. After the Japanese surrender, the Huks revolted in northern and central Luzon, sapping the strength of the new Philippine government.

The U.S. military aided the fight against the Huk insurgency, both to safeguard its installations and to make the base agreement more palatable to the host nation.

Manila thus relied heavily on Washington to solve some of its internal problems. The Vietnam war, however, reversed that equation.

President Ferdinand Marcos, elected in 1965, vocally supported the American war effort, but—despite significant pressure from President Lyndon Johnson—contributed only a small civil affairs contingent of around 2,000 troops. Citing the need to maintain domestic security in this all-important hub for the U.S. military, Marcos kept the vast majority of his troops at home while receiving still more aid.

During a visit to the White House in September 1966 he even leveraged renegotiation of an old nationalist sore spot, the lease on the American bases. He reduced the term from ninety-nine to twenty-five years, up for renewal in 1991. So valuable did Johnson and his successors consider Marcos’s support that they consistently overlooked the corruption for which his regime is now infamous.

All the while cooperating with the United States, Marcos burnished his nationalist credentials.

In his 1970 State of the Nation address, he stressed the need for a “re-orientation” away from the “marked colonial characteristics” of Philippine foreign policy. Along with revising the bases agreement, Marcos was a major advocate for a multinational “Asian Forum” to settle regional disputes without external intervention.

The Philippines became a charter member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), founded in 1967 to foster regional stability and cooperation. To the chagrin of the United States, Marcos did not align ASEAN with American interests, but forged close ties with Japan and, to some extent, China.

In 1974, Marcos even did away with the parity provision granting Americans property rights. Nonetheless, Washington remained steadfast in backing the Marcos regime.

Playing to nationalist sentiment, Marcos amended the base deal again in 1979. The United States acknowledged Filipino sovereignty over the facilities, ceded unused land, allowed the installation of Filipino commanders, and agreed to review the agreement every five years. In exchange, Marcos quietly agreed to the “unhampered” use of the bases, presumed by critics to mean the transfer and storage of nuclear armaments.

By the 1980s, accusations of corruption and repression mounted, and the Marcos regime’s days were numbered.

A growing opposition ignited on August 21, 1983, when Benigno Aquino, Jr., Marcos’s exiled political rival, was assassinated as he stepped off a commercial jet at the Manila Airport. The administration generally received the blame, perhaps nowhere more than in U.S. public opinion.

In February 1986, Marcos stepped down in the face of the “People Power” Revolution in Manila. Tellingly, he first sought refuge on Clark Air Base, then lived out the final three years of his life in Honolulu, Hawaii.

The United States retained strong ties to the Philippines after Marcos, but with the waning of the Communist threat, resentment over the American bases grew.

Finally, in September 1991, the Philippine Senate stunned Washington when it rejected the renewal of the Military Bases Agreement by one vote. The subsequent eruption of Mount Pinatubo, which did extensive damage to Clark and Subic, hastened the closure of the facilities.

By August 1992—ninety-four years after Commodore Dewey steamed into Manila Bay—the Americans were gone. Military aid dropped off, jobs on the bases vanished, and the legendary red light districts around Subic and Clark were left to find new customers.

|

| Ash from Mount Pinatubo collapses buildings at Subic Naval Base. |

Coinciding roughly with the collapse of the Soviet Union, the base closures marked an unprecedented low in Fil-American relations.

A partial shift occurred ten years later, on September 11, 2001, when the Philippines became one of the first nations to sign on to the War on Terror.

President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo offered the U.S. access to its former bases at Clark and Subic, and she agreed to bring in American advisers to combat terrorist groups in the southern, predominantly Muslim regions of the Philippines. With a nod to the fiftieth anniversary of the Mutual Defense Treaty, Arroyo depicted the arrangement as one of continuity, overlooking the previous decade.

American foreign policy once again meshed with internal threats to Philippine security, though the scale of intervention—fewer than a thousand advisers—was a far cry from the heyday of Fil-American cooperation.

Fully reversing the trend would require a greater threat to Philippine sovereignty. As it turned out, one was already coalescing off Luzon’s western shores.

Fighting In and Over the South China Sea

The South China Sea extends some 900 miles westward from the Philippines to Vietnam and stretches from China in the north to Borneo in the south. It hosts major global shipping lanes, valuable fishing, and prospective oil beds. This potential wealth, combined with a scattering of small, unpopulated islands, creates a perfect recipe for territorial disputes.

Malaysia, Indonesia, Brunei, Vietnam, and the Philippines all claim overlapping portions of the region, as do Singapore and both Chinas. The result has been a flurry of activity in recent years, including a steady arms race and a collection of strange public works projects.

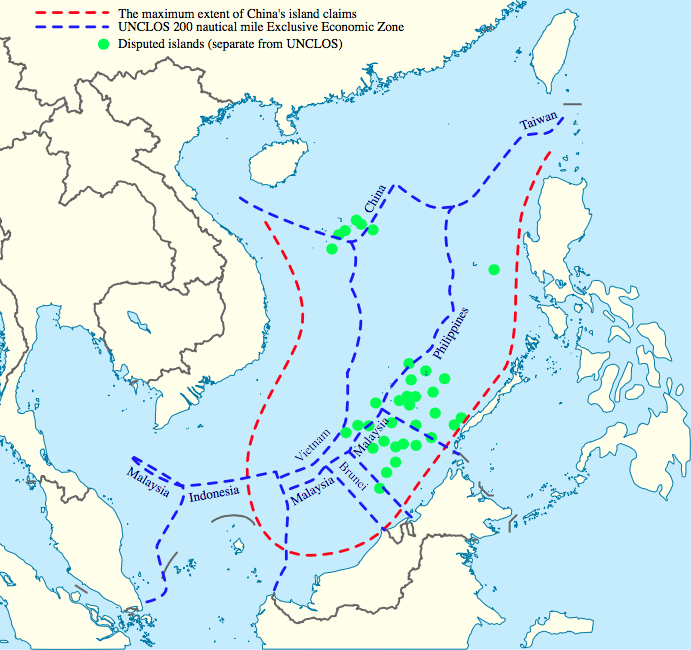

Why invest in these tiny, scattered islands? A partial answer is found in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

This agreement went into effect in 1994, setting guidelines for the management of undersea resources. As a general rule it defines territorial waters as those within twelve nautical miles of a nation’s coastline. A state can also claim an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of 200 nautical miles, within which it holds authority over natural resources, including fishing, minerals, and oil.

Such a convention is entirely dependent on two factors: active multinational enforcement and clear ownership of relevant coastlines. Neither is assured in the South China Sea.

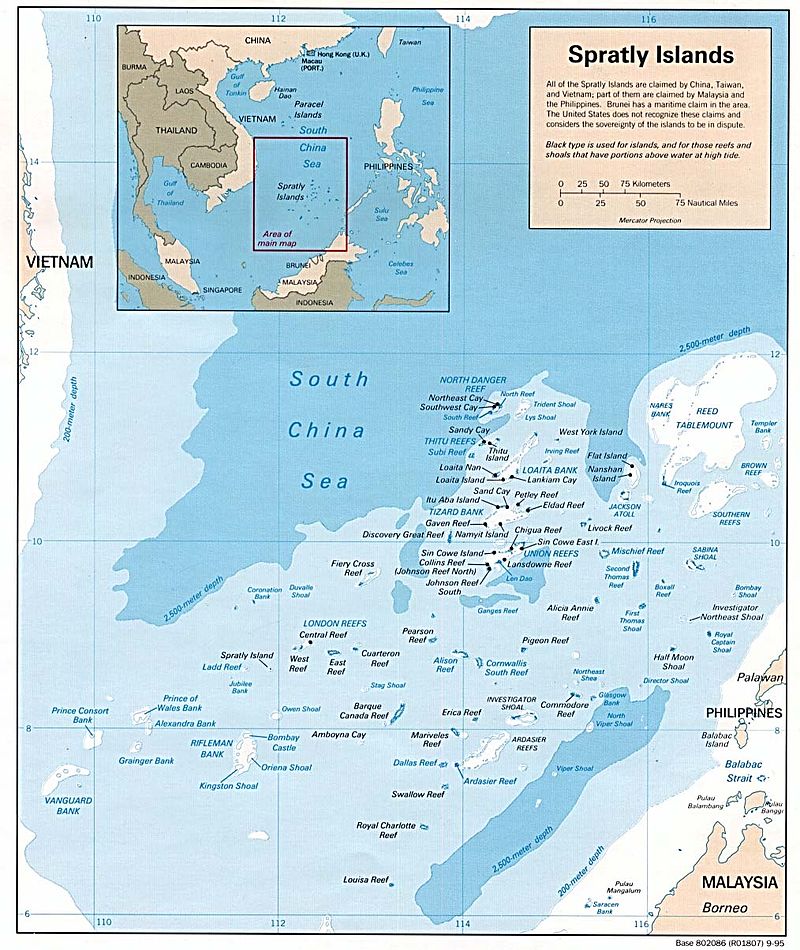

In the case of the Spratly Islands, directly to the west of the Philippines, multiple fisheries and the possibility of undersea oil have drawn the attention of Manila and Beijing, among others.

Both capitals are well aware that possessing the islands and submerged reefs constitutes nine-tenths of sovereignty over them and the surrounding waters. For the other tenth, they turn to history, dueling map exhibitions, and international bodies.

Though they are existentially at odds, the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of China (Taiwan) agree on an historical precedent that cedes them nearly the entire South China Sea. They point out that Chinese vessels explored the region during the Han Dynasty (second century BC) and that, centuries before the Europeans set sail, Chinese traders had dealings as far south as the Spratlys.

With the elimination of Japan as a regional power after World War II, Nationalist China saw an opportunity to solidify its claim, sending ships to occupy the Paracels, Pratas, and Spratlys. In 1947 it unveiled a map depicting an “eleven-dash-line,” asserting the full extent of Chinese territory in the South China Sea. In the 1950s, Communist China revised the U-shaped boundary to a “nine-dash-line,” in a friendly gesture to Vietnam.

|

| UNCLOS-mandated Exclusive Economic Zones overlaid against the nine-dash line. |

The dashed line has ever after formed the basis for both Chinas’ claims, and Beijing has commissioned exhibitions of documents and maps to prove its point. In response, rival nations like the Philippines have hosted competing displays.

Cartography aside, the line runs afoul of UNCLOS guidelines, which would leave much of the sea, including the Spratlys, out of China’s bounds.

Sensitive to this fact, China and Taiwan claim sovereignty over specific island groups and their corresponding territorial waters. Beijing has even organized the Spratlys and other islands into the large, diffuse prefecture of Sansha, complete with its own legislature on Yongxing Island.

|

| Map of the Spratlys. |

On Palawan Island, over 600 miles southeast of Yongxing, a Filipino mayor presides over Kalayaan, a municipality that also encompasses the Spratlys. The Philippine claim originates with Tomas Cloma, a wealthy Filipino businessman who allegedly discovered a subgroup of the Spratlys in 1947, dubbing them “Freedomland.” Imprisoned by the Marcos regime in 1974, Cloma ceded Freedomland to the Philippines for one peso.

In subsequent years, the Spratlys saw the addition of Vietnamese and Malaysian outposts alongside those from China, Taiwan, and the Philippines.

Mediators within ASEAN have continually tried to establish a “Code of Conduct” for the region to defuse tensions and preserve peaceful solutions. Meanwhile, a growing number of land reclamations, airstrips, and research stations have popped up at sea level, and tensions have continued to grow, not least between Beijing and Manila.

In February 1995, less than three years after the closure of American bases at Clark and Subic, China suddenly occupied Mischief Reef, arguably within the Exclusive Economic Zone of the Philippines.

The Chinese began pouring concrete pylons on the reef before diplomatic pressure from the Philippines and ASEAN helped to secure a hiatus. China eventually resumed construction, however, and in 1999 it completed several concrete buildings that were ostensibly shelters for Chinese fishermen.

Within months, the Philippine Senate voted to approve a new Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA) with the United States. The VFA eased the transit of American military aircraft and vessels through the Philippines and exempted American military personnel from visa requirements. Controversially, it also allowed the U.S. military to retain jurisdiction over servicemen accused of violating Philippine law.

It was hardly a coincidence that 1999 also saw the resumption of Fil-American military exercises.

The next turning point came in the Scarborough Shoal, 140 miles west of Luzon and 500 miles southeast of Hong Kong.

On several occasions in the 1990s, the Philippine Navy had expelled Chinese vessels in the shoal and detained their crews. By 2012, it was China’s turn to assert itself.

That April a Philippine warship attempted to detain several Chinese crews for illegal fishing, but Chinese surveillance ships blocked them from doing so. The Philippine vessel withdrew in accordance with a U.S.-brokered deal, but the Chinese ships remained. Within a few months, the Chinese erected a barrier to keep ships out of the shoal interior and effectively boxed the Philippines out of the area.

The Scarborough Shoal standoff immediately evoked nationalist displays.

In June 2012, President Aquino made official the name “West Philippine Sea,” while anti-Chinese boycotts harked back to the nationalistic stirrings of the turn of the century.

But a longstanding focus on internal security, combined with years of reduced military aid, left Manila in no condition to face down China. Rusting Philippine Navy vessels sat in the Spratlys, their crews watching ever more Chinese Coast Guard cutters and fishing boats pass by. As President Aquino was keen to point out, he didn’t even have a fighter jet to deploy.

Unwilling to apply force, Manila turned to the United Nations.

On January 22, 2013, the Philippines filed a request for arbitration in The Hague, arguing that China’s “nine-dash-line” violated its Exclusive Economic Zone, pursuant to UNCLOS. Ironically, the United States— which never ratified UNCLOS—applauded the move, while China—an UNCLOS signatory—rejected in advance any decision, arguing that the tribunal had no jurisdiction over questions of sovereignty.

A more immediate upshot was a rapid improvement in Fil-American military relations. During the standoff, requests for military aid began flowing once more from Manila to Washington.

Less than two years later, in April 2014, came the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement and President Obama’s visit. The U.S. military gained greater long-term access to Philippine installations and was authorized to “pre-position” military and humanitarian supplies on Philippine soil. Undoubtedly, massive American assistance after Supertyphoon Yolanda (also called Typhoon Haiyan) in November 2014 helped make the agreement more palatable, but the major motivation for it lay in the South China Sea.

While this recent strengthening of Fil-American relations is certainly in line with President Obama’s “ Asia pivot,” it marks a return to the twentieth-century norm of close collaboration that began in the American Period.

It also lends credence to the suggestion, supported by opinion polls, that Filipinos ultimately see an American presence more as a benefit than as a threat.

|

| Philippine and US Navy ships conducting exercises in the South China Sea, 2010. |

Meanwhile, tensions in the South China Sea fit well in the long history of the Philippines as a crossroads. Just as the West saw the archipelago as a stepping stone to Asia, now neighboring countries eye the Spratlys and other islands as the key to wealth, prestige, and regional stability. The future of the Philippines will be tied closely to developments off its western shore.

In other words, perhaps my tour guide had a point.

The opinions, views, and conclusions expressed or implied in this paper are solely those of the author and do not represent the views of the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Cohen, Warren. America’s Response to China: A History of Sino-American Relations. Fifth Edition. New York: Columbia University Press, 2010.

Gonzalez, Vernadette V. “Military Bases, ‘Royalty Trips,’ and Imperial Modernities: Gendered and Racialized Labor in the Postcolonial Philippines.” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 28:3 (2007), 28-59.

Hamilton-Patterson, James. America’s Boy: A Century of Colonialism in the Philippines. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1998.

Kaplan, Robert D. Asia’s Cauldron: The South China Sea and the End of a Stable Pacific. New York: Random House, 2014.

Karnow, Stanley In Our Image: America’s Empire in the Philippines. New York: Random House, 1989.

LaFeber, Walter. The Clash: U.S.-Japanese Relations throughout History. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1998.

Norman, Michael and Elizabeth Norman. Tears in the Darkness: The Story of the Bataan Death March and its Aftermath. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Girioux, 2009.

Schirmer, Daniel B. and Stephen R. Shalom, eds. The Philippines Reader: A History of Colonialism, Neocolonialism, Dictatorship, and Resistance. Boston: South End Press, 1987.

Tan, Antonio. The Chinese in the Philippines, 1898-1935: A Study of their National Awakening. Quezon City: R. P. Garcia, 1972.

Yu-Jose, Lydia N. Japan Views the Philippines, 1900-1944. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1992.

Zhao, Hong. “Sino-Philippines Relations: Moving Beyond South China Sea Dispute?” The Journal of East Asian Affairs 26:2 (Fall/Winter 2012), 57-76.

Online Resources:

China Daily feed on the South China Sea Dispute: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/world/2014southchinaseadispute/

GMA News Network (Philippines) feed on the South China Sea Dispute: http://www.gmanetwork.com