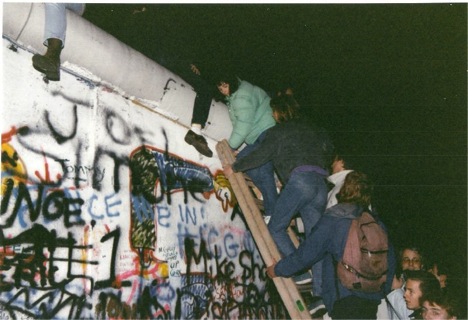

On November 9, 1989 the wall that had long separated East and West Berlin ceased to be. Apparently without warning, the impenetrable barrier between Western capitalism and Eastern socialism—and, more importantly, between peoples of shared nationality—became irrevocably porous. But the events of November 9 did not come from nowhere.

The fall of the Berlin Wall—as detailed by Mary Elise Sarotte—was the result of a series of insignificant gestures, of misunderstandings, of split-second decisions—in short, of happenstance. Sarotte does not explain November 9 as the culmination of geo-political diplomacy, a strategized win for those at the top of the political heap; she instead writes the history of serendipity whose outcome was far from predetermined, even if it seems so in retrospect.

|

Since 1949, the government of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) had loomed large over the lives of East Germans. It could be said that from the spring of 1989, Sarotte’s grassroots movers and shakers—journalists and politicians, bureaucrats and clergy, activists of both the accidental and intentional variety—began chipping away at the monolith of the GDR. Bit by bit, the authority of East Germany’s Socialist Unity Party (SED) was compromised; the leadership’s attempts to rebuild were clumsy and counterproductive. The stability of the Wall itself became precarious and on November 9 it began to fall.

As Sarotte tells it, the story begins in 1975 with the signing of the CSCE’s (Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe) Final Act, which brought the GDR under close scrutiny from the Western powers and the Soviet Union—whose guarantee of East German compliance also meant that they were able to lock-in in post WWII borders. The GDR’s heretofore-questionable record on human rights—including shootings at the Wall, the use of dogs, detainment, interrogation and proscription of movement—were now under review. With this framework in place, Sarotte shifts her focus to 1989 and the events that precipitated the collapse of the Wall.

Under the world’s magnifying glass, Sarotte argues, party leader Erich Honecker’s hardline policies grew evermore untenable. The cracks in the SED’s repressive regime were starting to show and on September 11, 1989, they widened. Hungarian borders opened to East Germans and a tidal wave of nearly 600,000 people escaped the GDR. By early October, East German attrition proved intolerable to Honecker, who sealed the state off entirely from both Hungary and ally Czechslovakia—from whose embassies flight was still possible.

|

Tensions in the GDR reached a boiling point with the Leipzig protests. On the macro level, Honecker’s misguided attempts to exert control—including his persistent praise of the authoritarian response to Tiananmen Square—backfired. On the micro level, Leipzig’s Stasi, or secret police, made a fateful decision to oust dissidents from their sanctuary in the Nikolai Church. Once turned outside, what had begun as a regular Monday night prayer meeting with a few clandestine activists gained momentum and ballooned into citywide marches.

The watershed moment came on October 9 when, unable to reach his superiors and overwhelmed by the sheer size of the crowd (at least 70,000 people), local party leader Hëlmut Hackenburg decided to shelve Honecker’s standing shoot order and let the Leipzing protesters pass unmolested. The impact of the decision was exponential: the doors opened as East Germans—indeed, the world—began to imagine a realm in which citizens of the GDR could stand up and the Stasi would stand down.

From October 9 to November 9, events picked up pace. Intention and impact became entirely divorced as the blundering SED struggled to regain control of its embattled republic. The Politburo ousted Honecker and, now under the aegis of Egon Krenz, sought stabilization through the drafting of a new travel law. The “concession,” however, was not well received. The Lauter draft offered no substantial changes to the existing policy, manifesting the leadership’s ultimate reluctance to grant freedom of movement to its people.

Protests followed and on November 9, hours before the fall of the Berlin Wall, a new draft was penned and released to the Politburo for approval. The provisions in the document were meant to fast-track the processing of travel visas for the upcoming holiday—though the requirement of applications and approvals remained. The new regulations were to be applied to all border crossings between East and West Germany and were to be instated, according to Lauter’s text, “right away.”

|

Assuming business as usual, the draft went largely un-reviewed by the delegates of the Politburo and it was casually passed to the SED press liason, Günter Schabowski, whose less-than-cursory examination of the document would prove auspicious. Moments later, a bungled press conference sent global tongues wagging. The immediacy and the scope of the new regulations were broadcast all over the world, while the crucial provision about permission remained publicly undisclosed. In the wake of the press conference, Germans on both sides of the Berliner Mauer began to gather hesitantly and excitedly. Their numbers quickly ballooned and the standoff between East Germans and their leadership reached its dramatic climax.

Sarotte brilliantly captures the feverish pace of the moments that followed. The fateful missteps, leaps of faith and frenetic energy that characterized the hours and minutes preceding the collapse of the wall are recorded in rich, evocative detail. Even with the benefit of hindsight, Sarotte’s retelling of the momentous night of November 9 is undeniably pregnant with possibility. The air of contingency is so palpable, so finely wrought, that one wonders if, in fact, the evening will end as we expect. Nevertheless, we find that, just after 11:30 pm, accident and ambition were resolved as the first crowd of East Berliners surged into the West. Subsequent attempts by a reactionary SED to reconsolidate their power came to naught…and the walls came tumbling down.