This is the story of a world turned upside down. So begins The Battle of Adwa: African Victory in the Age of Empire. While no attribution is suggested, it is likely Raymond Jonas had in mind the famous ballad played by the British at their surrender at Yorktown. As much as the victory by the colonials was a rebuke to conventional wisdom so the battle of Adwa was to European attitudes towards Africans during the Age of Imperialism.

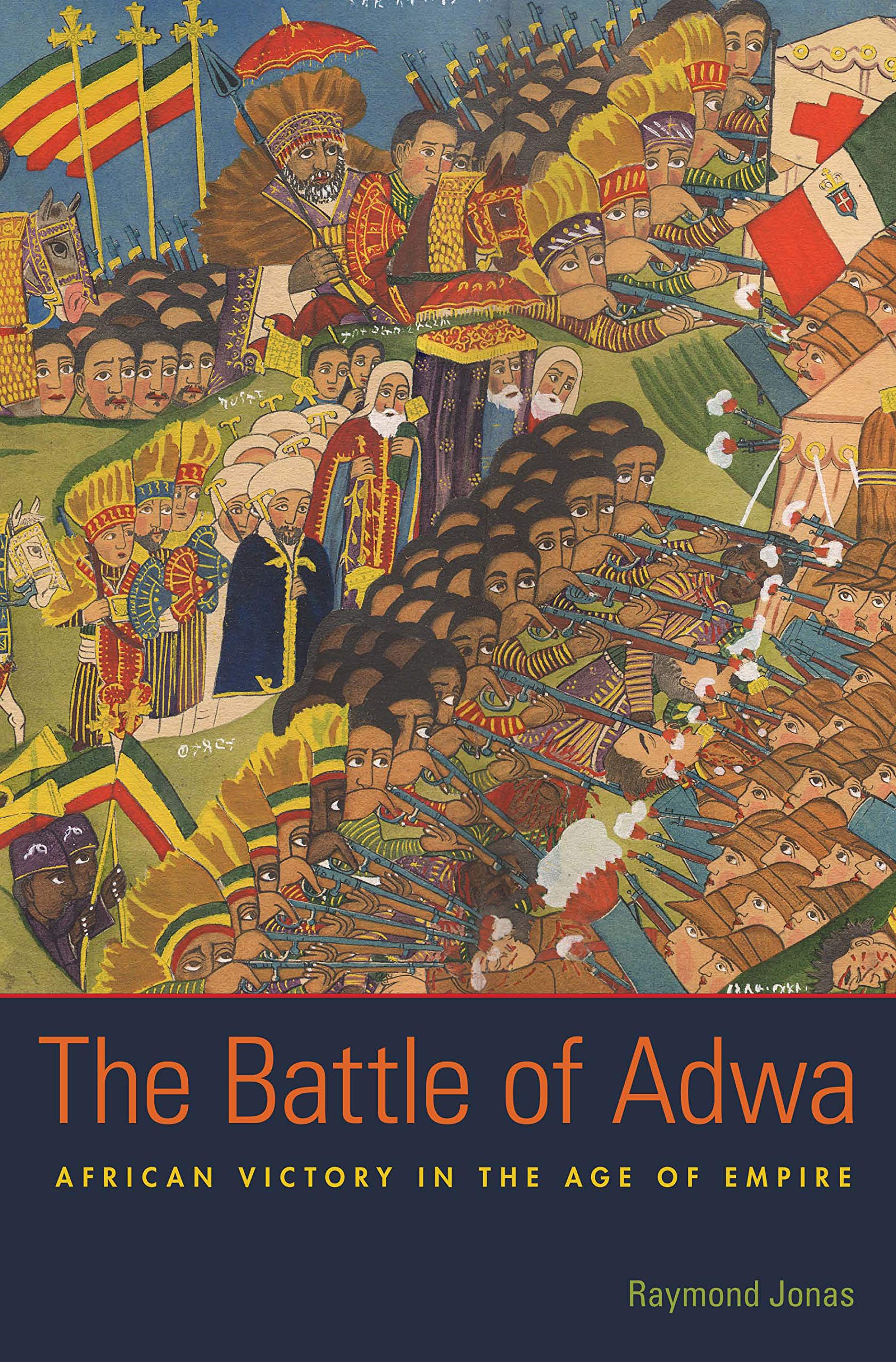

African Victory in the Age of Empire by Raymond Jonas.

The Battle of Adwa in 1896 was the result of Italian encroachments south of their colony of Eritrea on the Red Sea. Though bound by the Treaty of Wichale (1889) to friendship, the Italians and Ethiopians had different opinions about the nature of that friendship. This was the famous "mistranslation" where the Italian treaty indicated Ethiopia would be a protectorate of Italy, while Emperor Menelik II argued no such wording existed in his copy. After the Italians occupied the northern Ethiopian city of Adigrat Menelik summoned his forces and defeated the Italians at the battle of Amba Alage.

In response to this defeat thousands of Italian troops were ferried to Eritrea and, with great pressure from Rome to attack quickly, General Oreste Baratieri advanced and, due to a series of blunders by his subordinate commanders, his force was overwhelmed. Aside from numerous casualties, one mission reported roughly 3,600 dead though the exact number remains unknown, the Ethiopians also captured 1,900 Italians and 1,500 Askari (African soldiers serving in the Italian armed forces). The scope and scale of this victory - the campaign covered more miles than Napoleon's advance into Russia – should rank alongside any European campaign in the 19th century and assured Ethiopia as the only independent nation, apart from Liberia, in Africa at that time.

The Battle of Adwa is far from a simple battle narrative. Jonas structures the book into three sections covering the background, the battle, and the aftermath. By far the greatest effort on his part was uncovering a treasure-trove of Italian memoirs whose accounts humanize the battle. His narrative navigates seamlessly between commanders and commoners and sheds new light the conflict. The most difficult aspect of this review is summarizing this work but three themes emerge.

First, Jonas illustrates the fractured nature of Italian imperialism. As Adwa is held up as a symbol of resistance to colonialism it is ironic that Italy is given the position of imperialist archetype. If any quality typifies Italian colonial efforts it would not be jingoism but apathy. The Italian statesman Marquis d'Azeglio, after Italian unification, commented that "We have made Italy. Now we must make Italians." Italy was divided along religious, political, and regional lines. It was hoped by some, such as Prime Minister Crispi, that imperialism would improve the standing of the Italian government within the nation and across Europe. But even this small clique of colonialists demanded their aims be accomplished on the cheap.

It was just such pressure to win cheaply and quickly that made General Baratieri advance instead of his preferred defensive stand. The concern for cost was tied to the strong anti-colonial movement in Italy, due to having so recently been occupied by Austria, which was distinct in Europe. In response to the first defeat at Amba Alage students from the University of Rome marched through the street chanting "Viva Menelik!" and after Adwa there were legislative calls to abandon Africa entirely. This domestic scene is important as the willingness of Italy to accept defeat ensured Adwa was an Ethiopian success.

Second, Emperor Menelik II is shown to be a complex and engaging historical figure as well as a crafty politician. Too often heroes lose their humanity in the effort to place them on a pedestal and Jonas does admirable work in fleshing out the reality of Menelik. He documents the complex political web that Menelik had to navigate, and the admirable support he received from his wife Empress Taytu. It is hard not to see this marriage, linking the southern Shoa (Menelik) and northern Tigray (Taytu) regions of Ethiopia, as important as the one between Ferdinand and Isabella in unifying Spain. Jonas illustrates how Menelik slowly solidified his position, even using the Italians to help crush a rival claimant to his throne, and assured that Ethiopia entered the Battle of Adwa with a stronger domestic commitment to the conflict than his opponents.

Jonas also underscores Menelik's strategic acumen. For example, the Italians occupied the city of Adigat for over a year before Menelik confronted them. Rather than a sign of weakness, as the Italians believed, he used that delay to import European weapons to such an extent that his artillery outclassed those of the Italians. Jonas even offers the intriguing hypothesis that the supposed "mistranslation" of the Treaty of Wichale, the entire basis for the conflict, was a strategic choice. Jonas suggests that Menelik used his protectorate status to his advantage, such as a loan of four million lire from Italy used to purchase weapons, until his position was strong enough to claim there was a "mistranslation." These aspects of the story prevent Jonas' work from becoming a hagiography and leave the reader with respect for Menelik's decisions. These include his choices after the battle, such as not invading Eritrea and his care of the Italian prisoners, which preserved his strong negotiating position and assured he did not undo the effort he made in the European press, including a colored lithograph in Vanity Fair the 19th century equivalent to a Time cover, to foster sympathy for Ethiopia.

Third, Jonas illustrates how Adwa became a symbol for African, and African-American, resistance despite Menelik himself. Menelik saw Adwa as a way to solidify his rule and preserve his independence. The desire to see Ethiopia as a symbol of resistance came from others. Benito Sylvain of Haiti, a pan-African visionary, traveled to Ethiopia in 1904 to help celebrate Haiti's hundredth anniversary of independence. As Haiti was home of the first successful slave revolt, Sylvain saw a kindred spirit in Menelik. Far from finding a receptive audience, Menelik agreed that the "the negro should be uplifted" but noted that he was of little value as he was Caucasian. For a leader who had secured his position with the Dervishes against Italy by appealing to common "blackness" this suggests a malleable definition of race which Menelik would adopt based on his political goals. Much of the symbolism surrounding Adwa came from others, such as W.E.B. DuBois and others in the global African diaspora, after the end of the First World War.

Jonas claims that Adwa served as the model for future anti-colonial efforts. His narrative suggests that other resistance fighters learned lessons from the Ethiopian experience, such as using the press to build public sympathy. But the reader must infer them. In fact, exposing how the symbolism of Adwa developed far after the battle and divorced from Ethiopian support undercuts so much of the received wisdom that it is hard not to imagine most of the "lessons" are ex post facto rationalizations from other de-colonial conflicts. While he suggests that Adwa "set in motion the long unraveling of European domination of Africa" it is, again, a point the reader must accept on sentiment rather than evidence. Ethiopia was a shock to European self-assurance but was quickly forgotten which is why Europe was, again, shocked by Japanese victory against Russia in 1905.

Whatever the practical lessons Adwa provides, Jonas' book the Battle of Adwa documents the figures, both large and small, that took part in such a major turning point in history exceptionally well. His excellent archival work helps the reader see into the decisions made by the leaders, and humanizes the soldiers facing the consequences of these decisions, on both sides and leaves the reader leaves with a rich understanding of the significance of a battle which turned the world upside down.