Over the last decade or so, the Islamist group Boko Haram has been responsible for horrific acts of violence, thousands of deaths, and the displacement of one million people in Northern Nigeria and surrounding areas. While Boko Haram would appear to be a part of a wider terrorist phenomenon, linked to Al Qaeda and ISIS, historian Kim Searcy demonstrates that Boko Haram's agenda is local, not international, and the roots of that agenda stretch back several centuries.

Read these fascinating Origins articles for more on Africa: Islamist Groups in Egypt; A New World Order? Africa and China; Ethiopia and Nile River Tensions; Politics in Senegal; the Darfur Conflict; Piracy in Somalia; Violence and Politics in Kenya; Women in Zimbabwe; and Sport in South Africa.

Two years ago the world was gripped when Boko Haram kidnapped 279 school girls from the Nigerian town of Chibok. Despite the international attention, which goaded the Nigerian government to mount a rescue operation, the whereabouts of most of the girls remain unknown.

On May 5, 2014, following the kidnapping, Boko Haram’s leader Abubakar Shekau posted a video on the internet stating explicitly that neither he nor his followers acknowledge the Nigerian government.

|

“[We] need . . . to break down infidels, practitioners of democracy and constitutionalism, voodoo and those that are doing Western education in which they are practicing paganism,” he said. “All those with turbans [Muslim rulers] looking for opportunities to smear us, they are all infidels.”

Shekau’s rhetoric is consistent with Boko Haram’s violent insurgency, which has targeted Christians, Muslims, Nigerian government officials, and English-language schools.

The consensus among many academics, journalists, and commentators is that Boko Haram is an Islamist organization founded in 2002 in Borno state in northeastern Nigeria by the now-deceased charismatic cleric Muhammad Yusuf. Some say the rise of Boko Haram is part of the larger global phenomenon of Islamist terror organizations including Al Qaeda and ISIS.

In fact, rather than just a recent organization, the roots of Boko Haram lie deep in Borno’s past. The impetus for the group’s current activities can be traced back to three historical processes: the Islamic reform movements of the 19th century that took place in West and Central Africa, the changes wrought by the British colonial presence in northern Nigeria, and in the inter-ethnic conflict and struggle for natural resources that accompanied the creation of the modern state of Nigeria.

Empires and Islamization: 16th-18th Centuries

Maiduguri, the capital of the state of Borno in Nigeria, is Boko Haram’s current base of operations. Borno is now among the poorest states in Nigeria, but in the 13th century Kanem-Borno was one of the most extensive kingdoms in sub-Saharan Africa.

During this time, Islamic institutions and practice put down roots in the region. And Boko Haram’s social and religious identity is rooted in developments in the region over the following centuries.

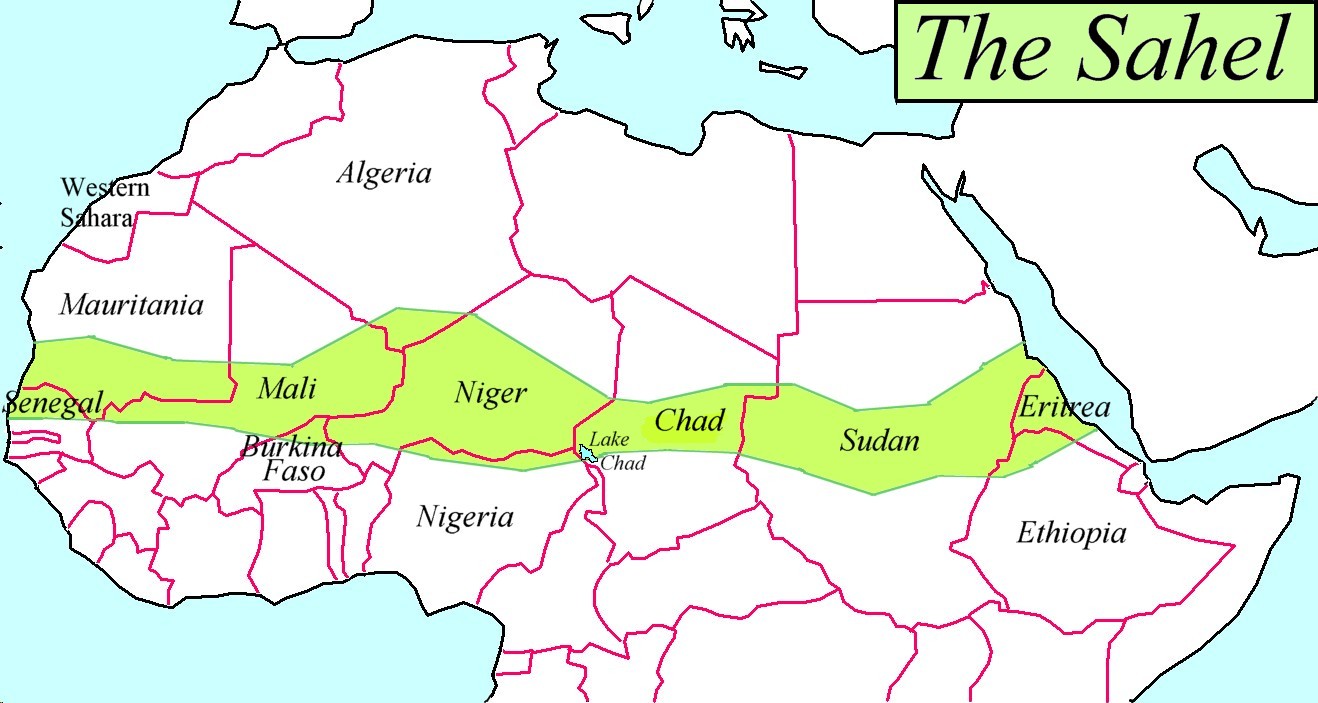

|

This region, known as the Sudanic Belt, encompasses the bio-geographic zone south of the Sahara, stretching from the west Atlantic coast of modern-day Senegal eastward to contemporary Eritrea, but bounded on the south by the forest and savanna regions of the continent.

Hummay, Muslim founder of the Sefuwa dynasty and the first mai (king) of Kanem-Borno, conquered the region in 1068 and encouraged the spread of Islamic institutions. The Sefuwa mais controlled large swathes of territory from the eastern shores of Lake Chad in the south to the oases of Fezzan, the southwestern part of modern Libya, in the north.

Hummay ruled for nearly 12 years, but the emergence of various more or less autonomous ethnic groups distinct from the Sefuwa ruling dynasty prevented the development of a centralized political system. In addition, Kanem, which consists mostly of desert and semi-desert, lacked the primary resources needed to make such a system viable.

|

A serious crisis finally led to the collapse of the Kanem state in the latter part of the 14th century. The mai Umar b. Idris (1382-87), with a group of his supporters, left for Borno to the west of Lake Chad where necessary resources could be found and where the Sefuwa had already settled their vassals. A large number of immigrants from Kanem had also already settled there. The Sefuwa’s main objective on their arrival in Borno was to build a strong regional economy to support a well-organized, Sefuwa-dominated political structure.

The period from about 1480 to 1520 was a time of active Islamization in the Sudanic belt. During this period many scholars from Mali, North Africa, Egypt, and the Saharan oases visited the region of West and Central Africa known as Hausaland, and contributed to the deepening of Islamic ideas and culture.

The Sefuwa mais of Borno had been Muslims since the 11th century and they traditionally surrounded themselves with Islamic scholars (ulama) who gave them an advantage over other rulers. Borno became a great intellectual center visited by scholars from Sudanic Africa and other parts of the Muslim world, and its cultural influence was felt outside its own regional sphere of influence.

Most scholars agree that Borno reached its zenith under the rule of Idris b. Ali (1564-c.1603). He was a skilled diplomat and keenly interested in Islamizing the region. In 1571, Idris b. Ali made the pilgrimage to Mecca, and upon his return he initiated many reforms in order to bring his country in line with other Muslim states.

He also forged strong diplomatic alliances with the sultans of the Ottoman Empire and the sultans of Morocco, which fostered trade relations between the three states. Borno’s primacy in Islamic education and control of trade led to its ascendancy in Sudanic Africa during this time.

The death of Idris b. Ali (c.1603) did not mark the end of Borno as an empire. Rather, it resulted in Ali’s conquests being consolidated under his successors and to the emergence of the Kanuri as a distinct ethnic group.

The term Kanuri came into use in the early 17th century, and referred to the dominant ethnic group of Borno. The majority of the Sefuwa mais hailed from this ethnic group.

|

Today the Kanuri continue to be the dominant ethnic group of Borno state in northeastern Nigeria. Though that ethnic group only makes up about eight percent of Nigeria’s total population, most of Boko Haram are Kanuri.

The Kanuri are distinguished from their Hausa and Fulani neighbors by their language and by the distinguishing vertical marks on each cheek. Both men and women have these markings. This custom of marking the faces of children was done to identify the family and ethnicity of a person, though the practice is now in decline.

Islamic religion is the defining cultural factor that unites the Kanuri people in Borno state. And Kanuri scholars credit their ethnic group for spreading and preserving Islam in the region.

Islamic Reform Movements of the 19th Century

Despite widespread Islamization, many areas continued to embrace a syncretic form of religion blending Islam with older animist religions. Islamic scholars railed against this religious syncretism and the Western Sudanic region witnessed a series of Islamic revivalist movements in the 19th century that sought to end this practice. Boko Haram is a direct descendent of these efforts to cleanse Islam of animist and other spiritual beliefs.

The primary objective of these Islamic reform movements was to restore Islam to what reformers saw as its original purity. These movements were led by a class of men who were devout, committed, and very learned in the Islamic “sciences”—the Quran, the traditions of the Prophet Muhammad, and Islamic law.

|

The ultimate goal of the reformers was to establish a state modeled upon the nascent Muslim state in 7th-century Medina. The reformers criticized the rulers and the common people alike because both engaged in this syncretic form of Islam. The ulama (scholars) had turned a blind eye to this blending of Islam with animism because they received patronage from the rulers.

However, the reformers looked askance at this compromise and preached openly against the rulers who married more than four wives, did not allow women to inherit, and, most egregiously, mixed Islam with animism. The rulers sought to resolve this conflict militarily, but were defeated. The old rulers were overthrown and replaced by devout reformers.

The participants in these revolts hailed from diverse social and ethnic backgrounds. But their leaders were mostly from the Fulani ethnic group. The most successful revolt occurred in what is now northern Nigeria and culminated with the formation of the Sokoto Caliphate.

By 1812, a Muslim empire emerged with the charismatic Fulani cleric, Uthman Dan Fodio, at its helm. Dan Fodio had defeated the corrupt and, from his perspective, irreligious, Hausa Muslim rulers of various kingdoms in the Western Sudan, and created an empire based upon the Prophetic precedent.

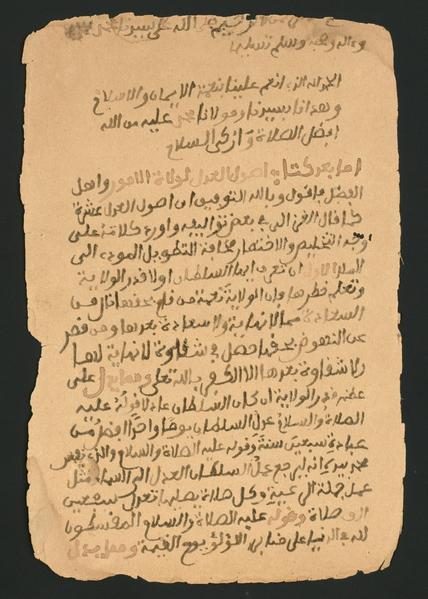

Borno was never conquered by Uthman Dan Fodio, but the revolts staged by him and his followers influenced a movement in Borno at the same time. This movement was led by Muhammad al-Amin ibn Muhammad al-Kanami, a scholar of the Kanembu people. (The Kanuri and Kanembu are closely related.)

|

Al-Kanami fought several campaigns to protect territory and by the mid-19th century had become the most powerful person in Borno. Muhammad al-Kanami died in 1838, and was succeeded by his sons. The last of these sons to rule Borno, Shehu Hashimi was defeated in a battle with the Sudanese warlord Rabih Zubayr ibn Fadl Allah in November 1893.

The British in Borno, and the Historical Impetus for Boko Haram’s Jihad

At the same moment, France and Great Britain were engaged in machinations to gain control of Borno, which was soon caught up in the tumult of competing colonial aspirations. British colonial policies—especially the granting of power to rulers of the former Sokoto Caliphate—had a direct effect on the development of Boko Haram’s ideologies and approaches.

When Borno was conquered by Rabih Zubzyr ibn Fadallah in 1893, he made Dikwa (54 miles east-northeast of Maiduri) his capital. In 1900, Rabih was killed by the French who then proceeded to restore the al-Kanami family to power in Dikwa. Then, in 1902, the British conquered Borno and incorporated it into its colonial possession known as the Northern Nigeria Protectorate.

In a case of imperial balance-of-power politics, Germany complicated matters by creating the West African colony known as Kamerun which included parts of contemporary eastern Nigeria. As a consequence, the British and Germans divided Borno between themselves. Dikwa became part of the German protectorate (1902-1916), and the British took control of the remnants of the empire of Borno. Dikwa then became part of British Colonial Nigeria in 1923, as one consequence of the First World War.

|

The British presence in Northern Nigeria was characterized by the policy of “Indirect Rule,” wherein colonial administrators chose compliant local rulers in order to preserve British interests in the region. Established local elites cooperated with the British in order to secure peaceful trade relations and oversee the collection of taxes.

All northern Muslim rulers were required to take an oath of fealty to the British crown. For their part, the British maintained that the rulers would not be required to do anything contravening the laws of Islam.

Despite their public pronouncements that they were interested in ruling in an even-handed, neutral manner, the British colonial administrators’ commitment to Indirect Rule required them to support those already in power and to quell any revolts, real or imagined, that might threaten the status quo.

Many British had a negative view of Islam. So the colonial administrators identified so-called “good Muslims” and placed them in positions of power and authority over the “bad Muslims.” The “good Muslims,” in the eyes of the British, were the former rulers of the Sokoto Caliphate because British officials considered them to be religiously moderate.

|

By contrast, they considered the Tijaniyya, Mahdiyya, and Sanusiyya Sufi orders to be fanatical and thus “bad Muslims.” The British believed that Islamic education would lead to fanaticism. And this conflict over education is the origin of the name “Boko Haram.”

Thus, the British and the former rulers of Sokoto had a symbiotic relationship that continued until Nigeria’s independence in 1960 and the creation of the Republic of Nigeria.

Independence, however, did little to change the political arrangements established by the British. The descendants of the Sokoto rulers who the British had placed in power continued to have the same relationship with the independent state of Nigeria, existing into the contemporary period. This reality is at the core of Boko Haram’s grievances.

Inheriting This History

Despite pledging its support for ISIS, Boko Haram is not really interested in a global reform or revivalist movement. Their sights and goals are local.

The goal of the movement, judged from the pronouncements of its former leader Muhammad Yusuf and its current leader Abu bakar Shekau, is to create an Islamic state in Northern Nigeria based upon the nascent Muslim state founded by the Prophet Muhammad in 7th-century Medina. Boko Haram seeks to emulate the precedent set by Uthman Dan Fodio and unite all the Muslims of Nigeria under their Boko Haram banner.

Muhammad Yusuf (left) and Abu bakar Shekau (right).

When Boko Haram was founded in the early 2000s, the aim of its leaders was to establish a Taliban-like government independent from the Nigerian government. In 2003, emulating the Prophet’s example when he abandoned Mecca for Medina in 622, Boko Haram expanded into Yobe State, near the Nigeria-Niger border and attempted to establish a Taliban-like community in the desert.

During this time Yusuf preached a doctrine of withdrawal, and did not seek to overthrow the Nigerian government. This move was also modeled on the example of Uthman Dan Fodio, who withdrew with his followers and attempted to establish a separatist community free from the corruption of the Hausa Muslim rulers. Muhammad Yusuf upon his death was succeeded by Abu bakar Shekau who continues the movement along the same ideological path as Uthman Dan Fodio.

Boko Haram was almost successful in its campaign until government security forces cracked down in 2003-2004. Former leader Muhammad Yusuf was killed in police custody in 2009.

The Guardian newspaper obtained a transcript of his last interrogation. In it, Yusuf maintains that his goal is merely to propagate Islam and remove western influences from the religious practices of Muslims in the region. According to Yusuf, it was anathema for true Muslims to operate within a system created by secular western civilization.

While Uthman Dan Fodio conquered large swathes of territory in what is now northern Nigeria, he was unable to conquer Borno in part, according to an editorial written by Tolu Ogunllesi that appeared in the February 4, 2015 edition of the Nigerian newspaper Premium Times, the Kanuri people have always considered themselves “immune from Caliphate rulership.”

Consequently, in spite of this reverence for Uthman Dan Fodio, the Boko Haram leadership has leveled an intense vitriol on the contemporary sultan of Sokoto. They have declared the sultan of Sokoto unfit to rule the Muslims of Nigeria because of his close relationship to the secular government of Nigeria, and the continuing indulgence of the sultan and his family members in syncretic religious practices.

Thus, Boko Haram maintains that it is the legatee of Uthman Dan Fodio’s Sokoto Caliphate, but instead of creating a locus of power centered in Sokoto, Boko Haram wants the locus of power to be shifted eastwards to Borno state.

According to Jacob Zenn of the Jamestown Foundation, this shift would lead to an economic and moral empowerment of the Kanuri people, who essentially have been marginalized since Borno’s incorporation in the Nigerian Federal Government in 1967. Michael Baca, an African affairs analyst, notes that the predominance of Kanuri within the ranks of Boko Haram is primarily a result of where the movement has its ostensible origins, especially the city of Maiduguri.

Their marginalization is a point of discontentment for many Kanuri who hark back to the days when their ancestors were the most powerful ethnic group in the region. From the 11th century to the 19th century, the Kanuri exercised a great deal of influence on the surrounding peoples.

However, it would be a mistake to claim that Boko Haram’s activities amount to a Kanuri Jihad or a “tribal insurgency” against the Northern Nigerian government controlled by Hausa-Fulani politicians. The majority of Boko Haram’s victims have also been Kanuri and many supporters from non-Kanuri ethnicities have been promoted through the ranks of the movement.

Boko Haram and the Struggle for Resources

Boko Haram’s origins are historically based, but economic resources, or the lack thereof, played a role in the formation and continuing existence of the organization. Nigeria is an oil-rich country mired in a great deal of political corruption. Hence, the majority of the population has not enjoyed any of the benefits afforded by this oil wealth. Those peoples living in Northern Nigeria are experiencing many economic privations because that region in particular is arid or semi-arid, and lacks many resources.

|

Thus, the dire economic conditions in Northeastern Nigeria serve as fertile recruiting grounds for Boko Haram. The Nigerian government has been unsuccessful in quashing this group because of its own weak political leadership and weak security institutions.

The identity of many of the people in the region revolves around their ethnic identity, rather than their national identity. As a consequence, when government forces invade the region under the pretext of putting an end to Boko Haram, but do so in a manner that violates the human rights of many residents in the region, peoples’ loyalties become divided.

Put starkly, the people face a choice.

Should they support an insurgency that has pledged to end corruption and return the pristine Islam of the Prophet’s time? Or should they support the government bent upon liquidating the Boko Haram organization that, according to the Guardian, is responsible for 13,000 deaths since 2010, one million internally displaced persons, and the kidnapping of 300 Chibok schoolgirls?

Since the Nigerian government has failed in its military counterinsurgency, it is perhaps time to try a different approach. That approach would be to end the political corruption, end the marginalization of Northeastern Nigeria, and open up the region for economic development. The region was at one time the wealthiest region in Africa.

What’s In a Name? The Meaning of “Boko Haram”

A look at the origins of the name “Boko Haram” highlights the historical roots of the movement. The organization’s formal name is Jammat Ahl as-Sunnah lid-Dawah wal-Jihad, which means the “People who Follow the Prophet’s Tradition for Proselytization and Jihad.” However, it is the group’s popular name, Boko Haram, that has taken on global significance.

Experts agree the name is loosely translated from the Hausa language as “Western education is forbidden.” According to the U.S. National Counterterrorism Center, the name “Boko Haram” is derived from a combination of the Hausa word book meaning “book” and the Arabic word haram, which means something sinful and, as a consequence, forbidden.

This consensus of opinion is founded upon two false assertions, however: first, that the organization has its origins in the 21st century, and second the etymology of the name Boko Haram.

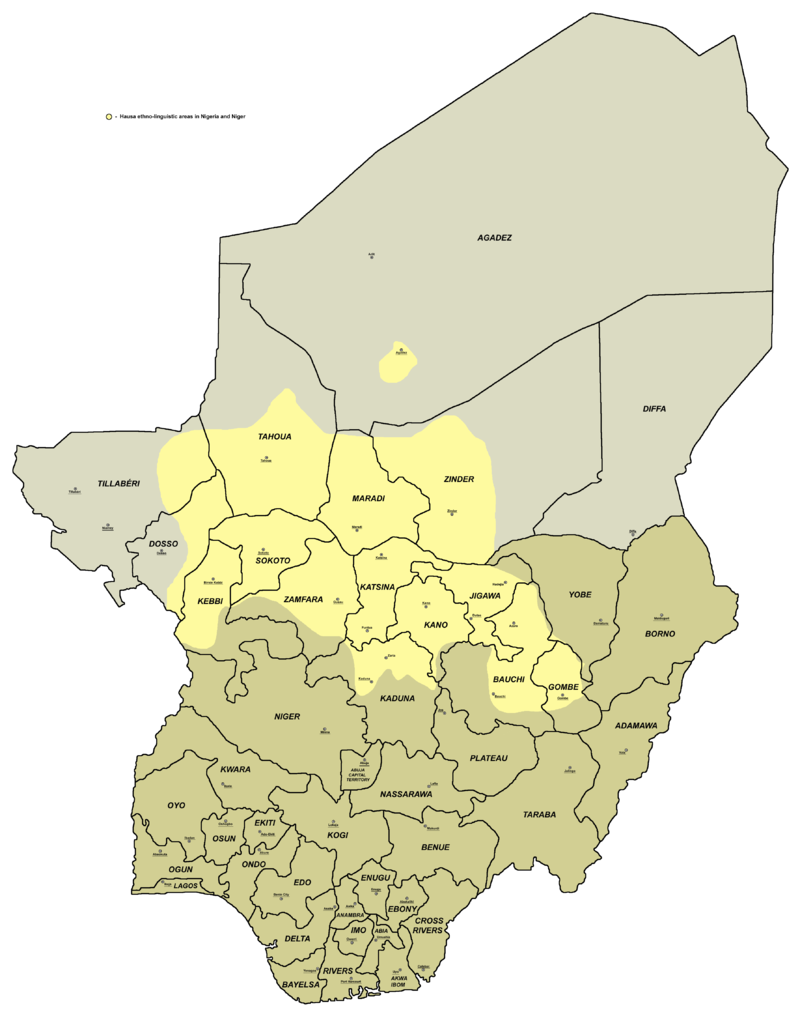

The etymological assertion that the word ‘boko’ is derived from the Hausa variant of the English word “book” is specious. Hausa is a member of the West Chadic languages subgroup of the Chadic language group which is part of the Afro-asiatic language family. The native speakers of Hausa are the Hausa people, and they are primarily found in Niger, northern Nigeria, and Chad.

|

While English serves as the official language of Nigeria, there are over 500 languages spoken in the country, and many Nigerians count English as their second or even third language. The groups’ initial activities began in Borno state, and there the primary language spoken is Kanuri. Hausa is, however, the lingua franca of many Muslims throughout West Central Africa and northwestern Sudan. Hence, the Kanuri speakers of Boko Haram would employ Hausa in their communications because it would reach a widespread and linguistically diverse audience.

According to Paul Newman, who is among the foremost authorities on Hausa linguistics, the word boko is not an English loanword that has entered into the Hausa lexicon, rather it is an indigenous Hausa word, and there is no relationship between the English word book and the Hausa word boko. The word for book in the Hausa language is littafi. The word haram is an Arabic loanword which means forbidden or sinful. Boko has a multiplicity of meanings denoting things or actions having to do with fraudulence, inauthenticity, or deception.

Newman notes that the false linkage between boko and the English word book was first made in a 1934 Hausa dictionary by a Western scholar that listed 11 meanings for the word – ten of them about fraudulent things and the final one asserting the connection to “book.”

Liman Muhammad, a Hausa scholar from northern Nigeria, 45 years ago presented the correct answer concerning the etymology of the term boko. Muhammad in his study produced a list of over 200 loanwords borrowed from English into Hausa in the area of “Western Education and Culture.” The word boko is not among the words on this list.

The Hausa word boko originally meant “Something (an idea or object) that involves a fraud or any form of deception” and, by extension, the noun denoted “Any reading or writing which is not connected with Islam.” The word is usually preceded with ‘Karatun’ [literally: writing/studying of]. ‘Karatun Boko’ therefore generally means, “Western type of Education."

The important issue here is that when the British colonial government began introducing its education system into Nigeria in the early 1900s, Muslim elites saw it as devoid of any intellectual or moral value, whereas traditional Quranic education was held in great esteem. Western education was seen as a fraudulent deception imposed upon the Muslim Nigerians by the conquering British.

Instead of sending their children to Western schools, the Hausa elites would send their slaves and servants in order to protect their children from the corrupting influence of western education. Their fear was that the traditional Hausa Islamic values would be undermined by the deceptions of the West, and the children would ultimately become ‘yan boko, that is “(would-be) Westerners.”

The way the word is used is also important. The word boko is always used as a modifier and rarely as an independent noun. For example, karatun boko or “western education,” literally means sham education or education of no importance, and rubutun boko, literally means “the Hausa language written in Roman script.”

The traditional opinion is that Hausa should be written in Arabic script rather than Roman script and when the former is undertaken it is a further attempt by the European conquerors to undermine Hausa Islamic cultural values. Hence, the name of the group is a shortened version of the Hausa language sentence karatun boko haram which means that western education is forbidden. Consequently, the roots of the Boko Haram group’s very name along with its ideology extend back to the British colonial period, and even earlier.

Mervyn Hiskett, The Development of Islam in West Africa (New York, 1984).

Robert Heussler, The British in Northern Nigeria (Oxford, 1968).

J. Fade Ajayi, ed., General History of Africa: Africa in the 19th Century until the 1880s (Berkley, 1998).

Jonathan Reynolds, "Good and Bad Muslims: Islam and Indirect Rule in Northern Nigeria." International Journal of African Historical Studies, 34 (2001): 601-618.

J. S. Trimmingham, The History of Islam in West Africa (Oxford, 1970).

Frederick John Dealtry Lugard, The Dual Mandate in British Tropical Africa (Oxford, 1922).

Paul Newman, The Hausa Language: An Encyclopedic Grammar (New Haven, 2000).