As COVID-19 has infected more than 90 million people in the first 13 months of the outbreak alone, governments around the world have urged social distancing measures as one way to contain the spread of the virus.

Though some have rejected the six-foot rule, along with mask-wearing and avoiding large social gatherings, these measures have a long history. Quarantine as a response to epidemics first emerged during the many plague outbreaks in Europe during the 14th century and were relied upon with increasing success thereafter to prevent disease from overtaking society.

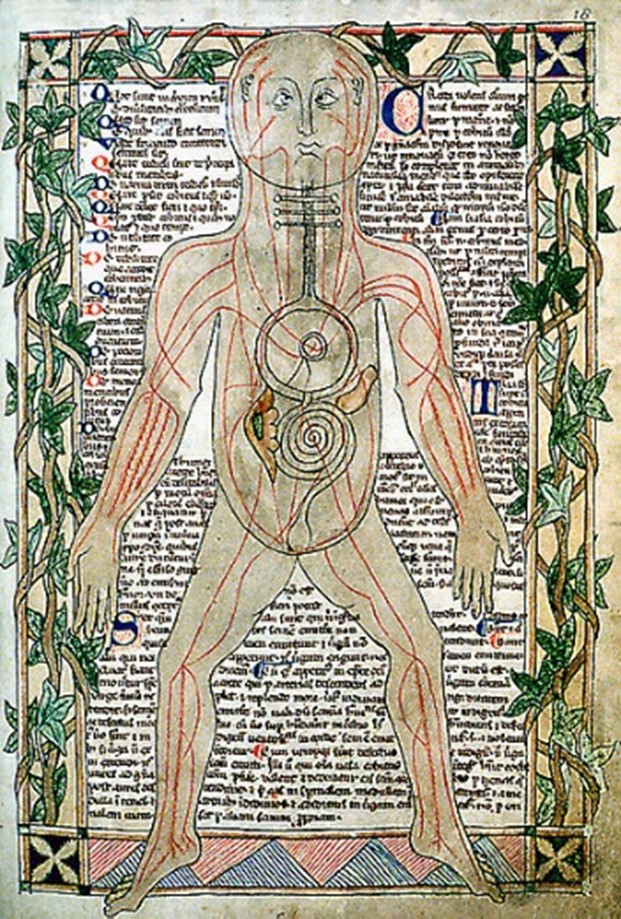

In the 14th century, people believed that the body was ruled by four humors: blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. This theory is attributed to the “father of Western medicine” Hippocrates, who argued in his medical writings that health was only achieved when “these constituent substances are in the correct proportion to each other, both in strength and quantity, and are well mixed.” Humoral theory, combined with ignorance of germs, created a situation ripe for unchecked outbreak.

Those who cared for the sick—from midwives, conjurors, and members of the clergy to surgeons and university-trained physicians—faced the plague utterly unprepared to treat it. Doctors resorted to trial and error, with a lot of unintended error, to discover possible effective methods to save lives.

They tried bloodletting; burning fires to “purify” the air; rubbing herbs, onions, diced snakes, or pigeon entrails on the body; and forcing the sick to drink vinegar, mercury, or arsenic. Others ate garlic or a compound made of iron oxide clay, aloe, myrrh, and saffron. The wealthy consumed crushed emeralds, ground up unicorn horns (a hard get to be sure), or theriac, a syrup made of various ingredients including opium that were aged for up to a decade before use.

It was discovered during the plague outbreak in 1361 that bursting buboes with a poker could slightly increase one’s likelihood of survival. By the 16th century, plague doctors adopted the infamous plague masks, believing that the long beak would keep them from breathing in bad air (or miasmas) around them and thus avoid getting sick. This was not the case.

These various efforts aside, in the words of Marchione di Coppo, “neither physicians nor medicines were effective. Whether because these illnesses were previously unknown or because physicians had not previously studied them, there seemed to be no cure. There was such a fear that no one seemed to know what to do.” Governments throughout Europe therefore gradually adopted the most effective methods for avoiding infection: social distancing and quarantine.

The word “quarantine” is directly taken from the Italian word quarantino, which referred to a 40-day period of lockdown that Italian doctors imposed when infectious disease broke out. Its first use was in 1377 when yet another wave of plague hit Europe.

In response, the city of Dubrovnik—called Ragusa in the medieval period, now in Croatia—instituted one of the first official plague quarantines. The ordinance prevented anyone traveling from plague-infected cities to enter Ragusa before first self-isolating in nearby towns. While the Ragusa lockdown measures were instituted for 30 days, the quarantino was frequently used thereafter.

These methods were first instituted somewhat haphazardly and on a very limited scope during the Black Death. Any quarantines that were imposed were more the result of panic and fear than organized social ordinances.

The Chronicle of the monastery of Neuberg recounts how “the inhabitants, frantic with terror, ordered that no foreigners should stay in the inns, and that the merchants by whom the pestilence was being spread should be compelled to leave the area immediately.”

John of Fordun, who died during the outbreak, meanwhile wrote that the disease “generated such horror that children did not dare to visit their dying parents, nor parents their children, but fled for fear of contagion as if from leprosy or a serpent.”

In some areas though more organized lockdowns were attempted.

Venice by 1348 required that all incoming ships isolate themselves for a time before the sailors were permitted to enter the city. Pistoia instituted ordinances of sanitation that required “no citizen of Pistoia or dweller in the district or the county of Pistoia . . . shall in any way dare or presume to go to Pisa or Lucca or to the county or district of either. And that no one can or ought to come from either of them or their districts.”

Those who attempted to violate these rules were given enormous fines while guards were placed at the city gates to prevent people from entering.

Luchino Visconti depicted in an eighteenth-century engraving (left). The coat of arms of the House of Visconti displayed on the Archbishop's Palace in Milan (right).

The most extreme measures were taken in Milan where the Visconti (the noble family that ruled the city) sealed off access as early as they could to prevent infection. When it reached the urban center anyway, the head of state, Luchino Visconti, ordered city officials to board up any home containing someone sick, closing the healthy in with the dying.

In 1423, Venice built a lazaretto, or plague hospital, on the island of Santa Maria di Nazareth. When individuals contracted the plague, they were removed to the island in hopes of keeping them isolated from the rest of the populace.

Other European cities adopted the practice in the next 100 years, situating these lazarettos in areas where they were separated from population centers either by natural barriers (such as rivers and seas) or by constructed barriers (such as ditches or moats). During outbreaks incoming merchants were increasingly isolated for a time in designated port buildings while imported products were put through “purgation,” which included ventilation or various forms of attempted disinfection.

Isola Lazzaretto Vecchio from the air.

The British finally adopted such measures in the 17th century, isolating sailors on ships suspected of carrying the plague in the Thames estuary until risk of transmission had passed. By the 18th century, forced isolation of those sick with a variety of communicable diseases—plague, yellow fever, smallpox, measles, and flu to name a few—was a widespread practice with many countries adopting legislation that enforced such measures in times of emergency. This includes the United States, where such measures were taken to limit the spread of yellow fever, among other diseases.

Social distancing measures to limit the spread of disease date back centuries. When enforced effectively, they have minimized infections when medicine has proven insufficient to cure the sick. As we confront the long task to vaccinate the world’s population for SARS-CoV-2, we should look to the past to guide our way in the future.