This month, three quarters of a century ago, the most famous battle of the Second World War began. More than four million combatants fought in the gargantuan struggle at Stalingrad between the Nazi and Soviet armies. Over 1.8 million became casualties. More Soviet soldiers died in the five-month battle than Americans in the entire war. But by February 2, 1943, when the Germans trapped in the city surrendered, it was clear that the momentum on the Eastern Front had shifted. The Germans would never fully recover.

A Soviet soldier waves the Red Banner near the central plaza of Stalingrad, 1943.

Fourteen months before Stalingrad began, Hitler had launched Operation Barbarossa, the largest military offensive in human history. After two years of decisive victories over France, Poland and others, Hitler and the German High Command (Oberkommando des Heeres, or OKH), were confident that the Soviet Union would fall within six weeks. At first, their prediction seemed correct: the attack in June 1941 caught Stalin unawares, and the Red Army unprepared. By December, the Red Army had suffered nearly five million casualties.

But despite enduring staggering losses, the Red Army continued to resist. In August 1941, senior members of the Wehrmacht began growing increasingly uneasy. The Chief of the OKH staff, General Franz Halder, noted in his diary that ““It is becoming ever more apparent that the Russian colossus…. Has been underestimated by us…. At the start of the war we reckoned with about 200 enemy divisions. Now we have already counted 360… When a dozen have been smashed, then the Russian puts up another dozen.”

In October, the Wehrmacht launched Operation Typhoon, the effort to take Moscow and end the war by Christmas. But as the weather grew bitterly cold, the German offensive ground to a halt, and was then pushed back by a Soviet counteroffensive. The front line froze in place some two hundred kilometers west of Moscow – and 1400 kilometers east of Berlin.

During the bitter winter months, the OKH began planning for a renewed counteroffensive in the spring, hoping to achieve the decisive victory that had evaded them in 1941. Thus was born Operation Blue, an attack to seize the oil fields of the Caucasus, and then drive on to the Volga. Launched in June 1942, it caught the Red Army off-guard, as they had expected a renewed push towards Moscow. Within two weeks, the Wehrmacht advanced more than 300 miles.

Hitler, increasingly directing military operations in Berlin, decided to shift his offensive in early August. For both symbolic and strategic reasons, he ordered the Sixth Army under General Friedrich von Paulus to advance towards the city of Stalingrad. By August 23, the Germans were in the suburbs, where fighting turned ferocious. Bombed into rubble by German aircraft and artillery, the city became impassable to tanks and ideal terrain for defenders.

The Stalingrad Flour Mill: the mill, near the waterfront, was one of the few buildings to remain relatively intact throughout the battle. It was preserved as a memorial and part of the Battle of Stalingrad Museum after the war. (Author’s Collection)

As the Germans approached Stalingrad, Stalin issued Order No. 227, with its famous command: “Ni Shagu Nazad!” [Not One Step Backwards!]. This meant a horrific price for the Soviet defenders within the city of Stalingrad. Outnumbered and without air cover, the 62nd and 64th Soviet Armies suffered enormous losses: the 13th Guards Division, entering the battle with over 10,000 men, virtually ceased to exist; it suffered 80% casualties in its first week in the city alone.

In September, Stalin sent General Vasily Chuikov to take command of the embattled survivors of the 62nd Army in the city itself. They were tenaciously clinging to rubble on the west bank of the Volga, with only a few hundred meters between its front lines and the river to its back.

Chuikov recalled the grim moment: “When I got to army headquarters I was in a vile mood. Three of my deputies had fled… But the main thing was that we had no dependable combat units, and we needed to hold out for three or four days…We immediately began to take the harshest possible actions against cowardice. On the 14th I shot the commander and commissar of one regiment, and a short while later, I shot two brigade commanders and their commissars. This caught everyone off guard. We made sure news of this got to the men.”

Despite his brutality, Chuikov earned the respect of his soldiers, taking the same risks they did. He was buried alive twice by German bombardments, and kept his headquarters in the city, less than two hundred meters from the German front line.

The Germans poured more and more men into the battle at Hitler’s command. By November, the OKH had committed 1.2 million men, or about a third of its strength, to the southern front.

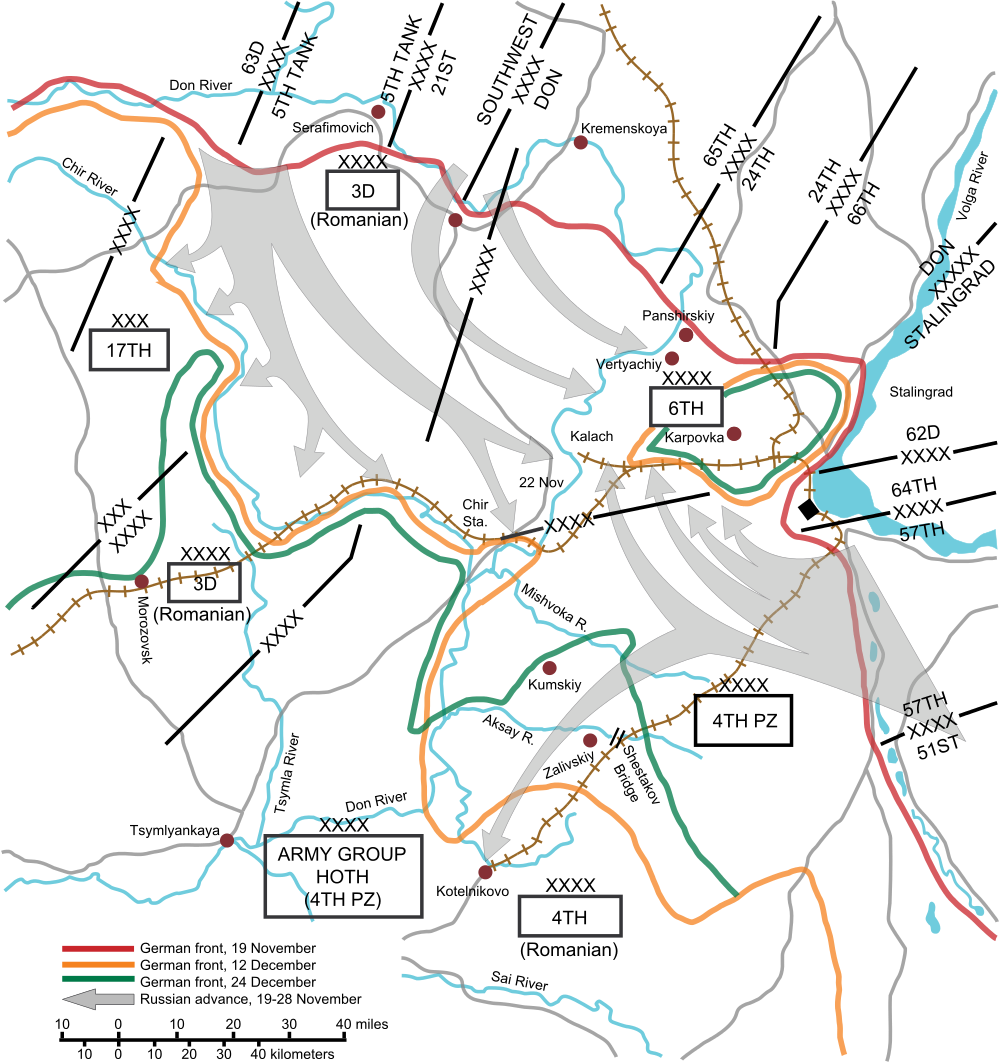

As the fighting reached its fevered peak in the city itself, Generals Alexander Vasilevsky and Georgy Zhukov at Stavka (the Red Army High Command) came up with a master stroke to counter the enormous pressure on the city. They proposed a massive double encirclement of the entire German Sixth Army. Stalin approved their plan – Operation Uranus – on November 13.

The Frontlines at Stalingrad from the beginning of Operation Uranus to the end of the battle.

On the snowy, foggy morning of November 19, the Soviets struck. 1.2 million Soviet soldiers drove into the weakly guarded flanks of the German Sixth Army. Within four days, they had encircled 300,000 Axis soldiers, trapped in a frozen wasteland in and around Stalingrad. German attempts to break into the pocket failed. Over the next three months, the Red Army began to squeeze the life out of them. Efforts at supplying the kessel (cauldron) via air proved beyond the Luftwaffe’s declining capabilities.

By December, when German airlifts ceased, life in the kessel became a living hell. As one German soldier recalled: “We were so weak and exhausted and there were so many dead lying around in the open frozen stiff, that we could not bury our own comrades.”

Soviets defend a position in Stalingrad, 1943.

As rations reached zero, sentries froze to death on guard duty. A typhus epidemic ravaged the survivors. Medical treatment proved impossible; the badly wounded or sick were left outside to freeze to death, as a “mercy” to the longer death from starvation or infection. Rumors of cannibalism grew increasingly frequent.

As conditions became unbearable, Hitler ordered his men to fight to the last. In an effort to encourage his commanding general, he made Paulus a field marshal on January 30; as no German field marshal had ever surrendered, Hitler hoped Paulus would kill himself rather than be captured. Instead, on January 31, 1943, Paulus surrendered the 91,000 skeletal German soldiers still left under his command; some would fight on until February 2. Only 6 percent would survive Soviet captivity.

The remains of central Stalingrad after the end of the battle in February 1943 (RIA Novosti).

The Germans would launch one more major offensive – Kursk – in July 1943, but it failed. Stalingrad marked the shift of initiative to the Red Army on the Eastern Front. There were no more decisive victories for the Wehrmacht in the east. Despite the importance of the battles of Moscow, Kursk, and Operation Bagration, it was Stalingrad that would be immortalized around the world for turning the tide for the Allies in World War II.

Rodina Mat’ Zovyot (The Motherland Calls), a 279 foot statue, crowns Mamayev Kurgan, a hill in central Stalingrad that witnessed nearly constant fighting throughout the battle, and contains the skeletal remains of more than 35,000 soldiers. (Author's Collection)

Learn more about the Battle of Stalingrad:

Anthony Beevor. Stalingrad: The Fateful Siege, 1942-1943. New York: Penguin Books, 1999.

David Glantz and Jonathan M. House, To the Gates of Stalingrad (Volume 1, 2009), Armageddon in Stalingrad (Volume 2, 2009), Endgame at Stalingrad (Volume 3, 2014). Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas.

English-language Primary Sources on the Battle of Stalingrad:

Jochen Hellbeck. Stalingrad: The City that Defeated the Third Reich. Philadelphia, PA: Public Affairs, 2016.

Reinhold Busch. Survivors of Stalingrad: Eyewitness Accounts from the 6th Army, 1942-1943. London: Frontline Books, 2014.

Learn more about the Eastern Front:

Chris Bellamy, Absolute War: Soviet Russia in the Second World War. New York:Knopf Doubleday, 2008.

Evan Mawdsley, Thunder in the East: The Nazi-Soviet War, 1941-1945. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2015.