December 16, 1971 marked the end of the Bangladesh Liberation War, a short-lived conflict between India and Pakistan that established the People’s Republic of Bangladesh from the territory of the former province of East Pakistan.

Although the war is best remembered for its dramatic alteration of South Asia’s geopolitical landscape, it also bears a more complex and lesser-known set of legacies for how we think about Cold War international relations, twentieth-century genocidal and sexual violence, and the limits of international law in post-conflict societies.

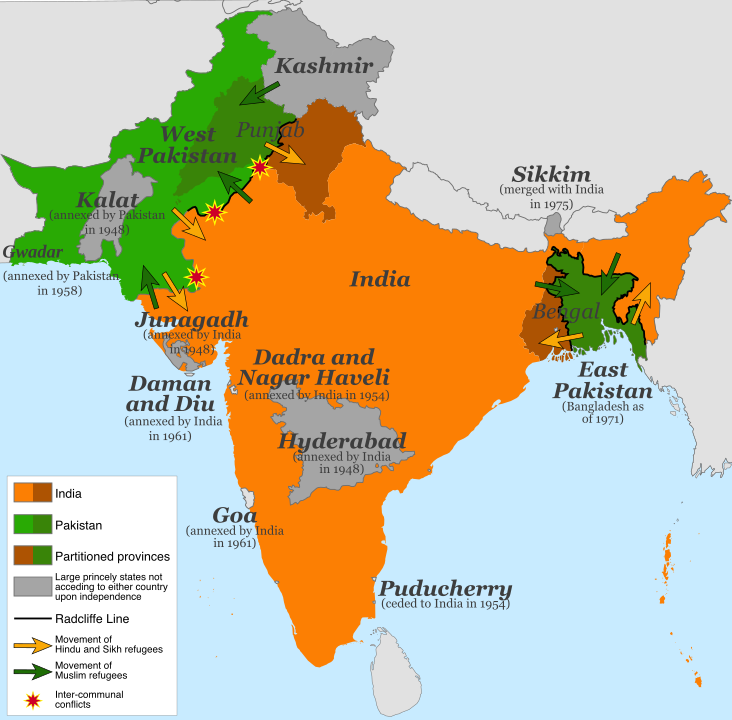

Map of the 1947 partition of India, where orange represents India and green represents Pakistan.

The province East Pakistan was created during independence from the British empire in 1947. At that time, the South Asian subcontinent was partitioned into two countries: India (including lands with a Hindu majority) and Pakistan (lands with a Muslim majority). The people and territory of East Bengal became East Pakistan.

East and West Pakistan were geographically, culturally, and ideologically distant and distinct. An independence movement for East Pakistan grew up based on Bengal ethnic concerns, the right to use the Bengali language, and a desire for local political control and self-rule.

The seeds of political crisis that led to the Liberation War were planted on December 7, 1970. The Awami League won a substantial victory in Pakistan’s elections. The League was a political party led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, who had campaigned for autonomy for East Pakistan. However, they encountered immediate opposition from General Agha Muhammad Yahya Khan and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto of the Pakistan People’s Party, which attempted to prevent the Awami League from forming the next government.

After months of fruitless negotiations, the Pakistani army was deployed in East Pakistan on March 25, 1971. It pursued a policy of reprisal, targeting supporters of Bangladesh liberation and perceived enemies of the state like the significant Hindu minority.

Bangladesh nationalist poster depicting atrocities at the hands of the Pakistani army in 1971.

Deploying weapons such as fighter jets, tanks, and napalm—and creating radical religious militias to participate in the systematic murder and deportation of the populace—the army of Pakistan committed war crimes that reached the level of genocide.

What began as an internecine conflict soon became an international one. A Bangladesh independence militia called the Mukti Bahini, which drew support from the government of India, often engaged in guerilla operations in East Pakistan from bases on the Indian side of the border.

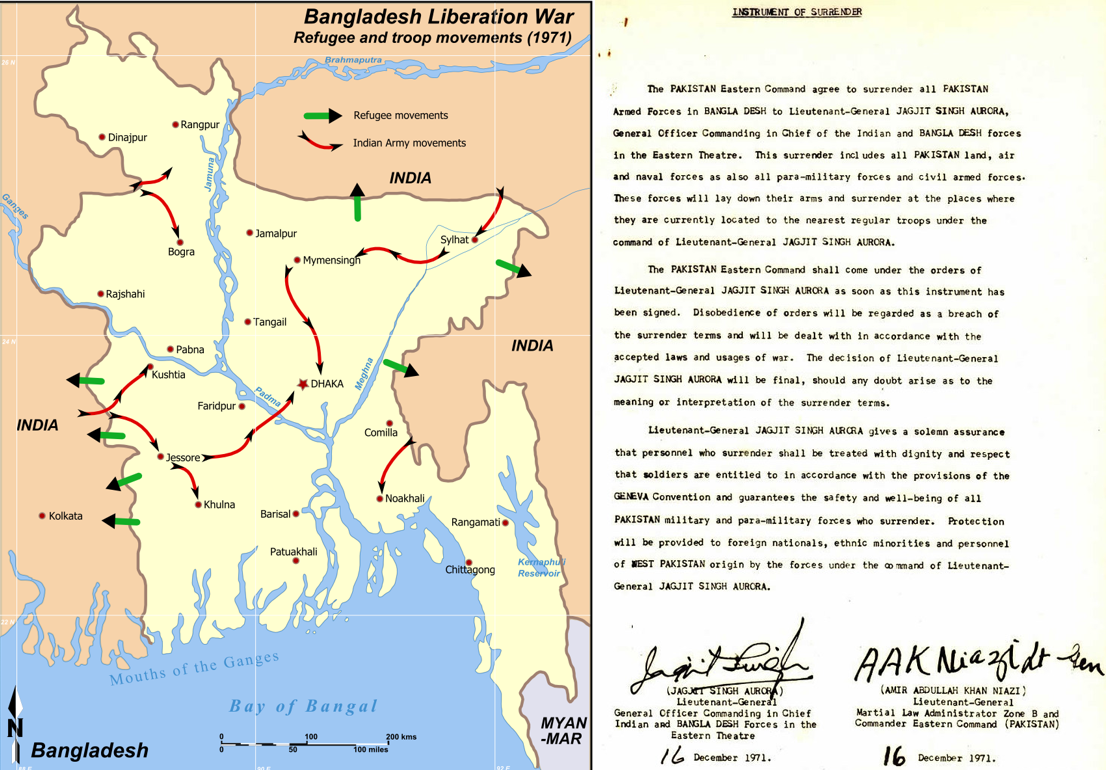

With as many as 15 million refugees crossing into its territory by autumn 1971, India decided to intervene militarily in the autumn for “purely humanitarian reasons” according to Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. Pakistan preempted Indian action, however, by attacking northern India from West Pakistan on December 3.

Map of Bangladesh Liberation War refugee and troop movements in 1971 (left). Text of the Instrument of Surrender, 1971 (right).

Although the fighting lasted for only two weeks before a Pakistani surrender, the war became a flashpoint within the wider Cold War. Fearing that an Indian victory would pave the way for Soviet domination in the region, the United States did what it could to buttress Pakistan from the outset.

The Nixon administration had, for example, dispatched the aircraft carrier Enterprise into the Bay of Bengal as a deterrent to Indian military intervention. It also refrained from criticizing the ongoing humanitarian crisis, publicly declaring between March and December that the conflict remained a Pakistani internal matter.

Even as American diplomats at the consulate in Dhaka futilely sounded the alarm over the ongoing “selective genocide,” the White House illegally transferred weapons to Pakistan in direct violation of a Congressional sanction. The U.S., in other words, was complicit in an unfolding humanitarian crisis of astounding magnitude.

Estimates of the death toll vary, stretching from hundreds of thousands to some 3 million. Furthermore, the Pakistani army used rape as a weapon of war. At least 200,000 women were assaulted and some 25,000 children resulted from those attacks.

The memory of those events remains contested. The government of Pakistan has never acknowledged that any atrocities were committed during the war and continues to insist that only a few thousand people were killed. In the slim literature on the subject, scholars have debated whether the Pakistani army’s actions qualify as genocide and who should be held responsible.

Exhibition at the Liberation War Museum in Dhaka displaying human remains and war materials.

In Bangladesh, the political consequences of the Liberation War continue to resonate. Awami League governments led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (known as Mujib, 1973-75) and Sheikh Hasina (1996-2001; 2009-present) have sought to punish those who collaborated with Pakistan and enacted the 1973 International Crimes (Tribunal) Act and the 2009 International Crimes (Tribunals) (Amendment) Act (ICTAA). By 1975, some 752 people had been convicted and imprisoned.

But, despite their names, these tribunals remained solely Bangladeshi in scope and have never been affiliated with the International Criminal Court, leading some observers to claim that the trials have not met international standards.

At times, justice has appeared more distant than ever.

Individuals who aided the Pakistani army, or who were involved in the assassination of Mujib in 1975, have served in the governments of General Ziaur Rahman (1975-81), General Hussain Muhammad Ershad (1982-90), and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party led by Khaleda Zia (1991-1996; 2001-2006). General Ziaur Rahman halted the war crimes trials and they did not resume until 2010 under the ICTAA.

The legacy of the Liberation War continues to shape civic life in Bangladesh today. As trials have been conducted in recent years, there have been violent protests by both their opponents and by those demanding harsher sentences for those convicted. Since 2013, there have been a series of murders of prominent secularists and human rights activists by Islamists in what appears to be retaliation for the trials.