December 11, 2018, marked the one hundredth birthday of Alexander Isayevich Solzhenitsyn. Born in southern Russia thirteen months after the Bolshevik Revolution, the only son of a mother whose husband had died in a hunting accident while she was pregnant, Solzhenitsyn would achieve worldwide fame as an author and a dissident, be imprisoned, pardoned, exiled, forgiven, embraced, and forgotten by his native land. Solzhenitsyn would also outlive both the Soviet experiment and the twentieth century, dying in his 90th year on August 3, 2008 in Moscow.

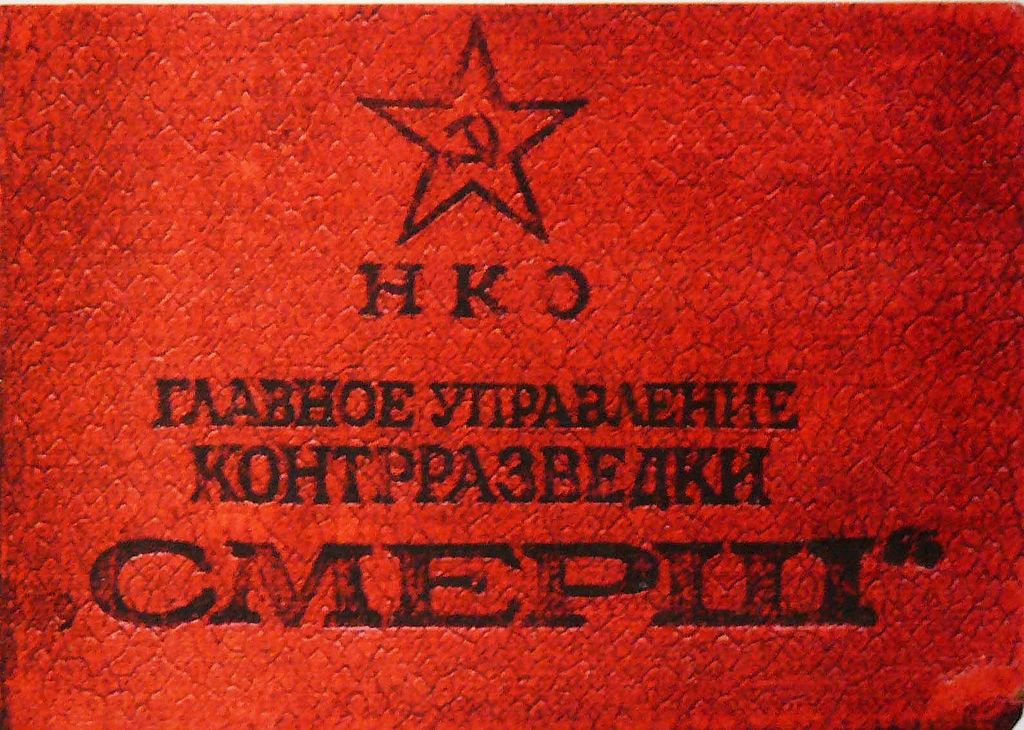

A mathematician by training, Solzhenitsyn served in the Red Army as an artillery officer during World War II and was decorated for bravery, but near the end of the war he was arrested at the front by SMERSH, the Soviet counter-intelligence agency, for writing derogatory comments about Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin in a private letter to a friend. Convicted under the infamous Article 58 (anti-Soviet propaganda and agitation), Solzhenitsyn spent eight years in various prisons and labor camps.

A SMERSH identification card; Solzhenitsyn was arrested by SMERSH for writing derogatory comments about Stalin in a private letter.

He portrayed one of these, a so-called sharashka or special prison—a scientific research facility where the talents of prisoners could be directed toward the defense of the Motherland—in his novel First Circle, and another, a mining camp in Kazakhstan, in his novella One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich.

Solzhenitsyn’s sentence continued after he was released from prison camp, and he was supposed to live in exile in Kazakhstan for the rest of his life. Transferred to Tashkent, Uzbekistan for cancer treatment instead, Solzhenitsyn built the plot of another novel, the magisterial Cancer Ward, around this experience.

Political prisoners in Kengir, Kazakhstan, the site of a famous prisoner revolt. Solzhenitsyn portrayed life in a camp in Kazakhstan in his book One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich.

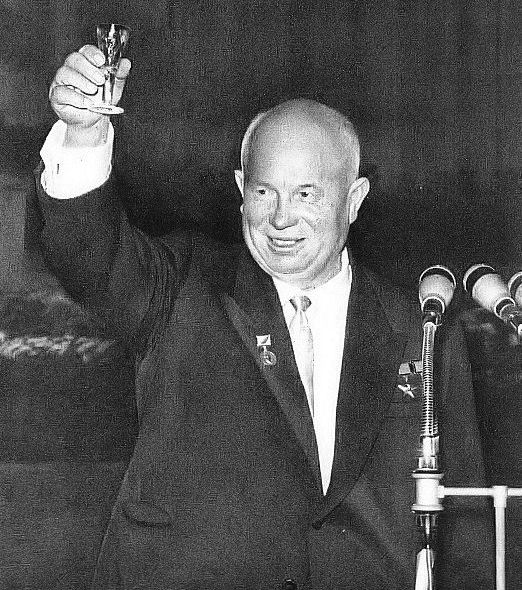

Before 1956 it seemed unlikely that Solzhenitsyn would ever become a published author. But after Nikita Khrushchev’s “Secret Speech” his exile was commuted and Solzhenitsyn was permitted to return to central Russia, where he taught school while secretly writing fiction at night. He also began to research and write a non-fiction work about the forced labor camp system.

In 1960 Solzhenitsyn approached the editor of the literary journal New World (Novyi Mir), Alexander Tvardovsky, and offered him the manuscript of One Day. Thanks in great part to the support of Khrushchev himself, who was determined to “root out” the evil of Stalinism, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich was published in the Soviet Union in 1962. Solzhenitsyn went on to publish three more stories in New World in 1963 before times changed (again) and he ceased to be able to publish new fiction.

After Nikita Khrushchev’s “Secret Speech,” Solzhenitsyn’s exile was commuted and Solzhenitsyn was permitted to return to central Russia.

For Soviets, reading about the “Gulag” was a shock, even if in a work of fiction. Throughout the horrors of Stalin’s purges in the 1930s, during World War II, and in the aftermath of the war, when trainloads of Soviet soldiers were sent directly from Western Europe into the camp system, the Soviet people remained silent, terrified that the knock might come on their own door at any time.

Solzhenitsyn’s name will forever be associated with the word Gulag, which was burned onto the historical consciousness of the West by what Solzhenitsyn called his “literary investigation” into the system of Soviet prison camps—The Gulag Archipelago.

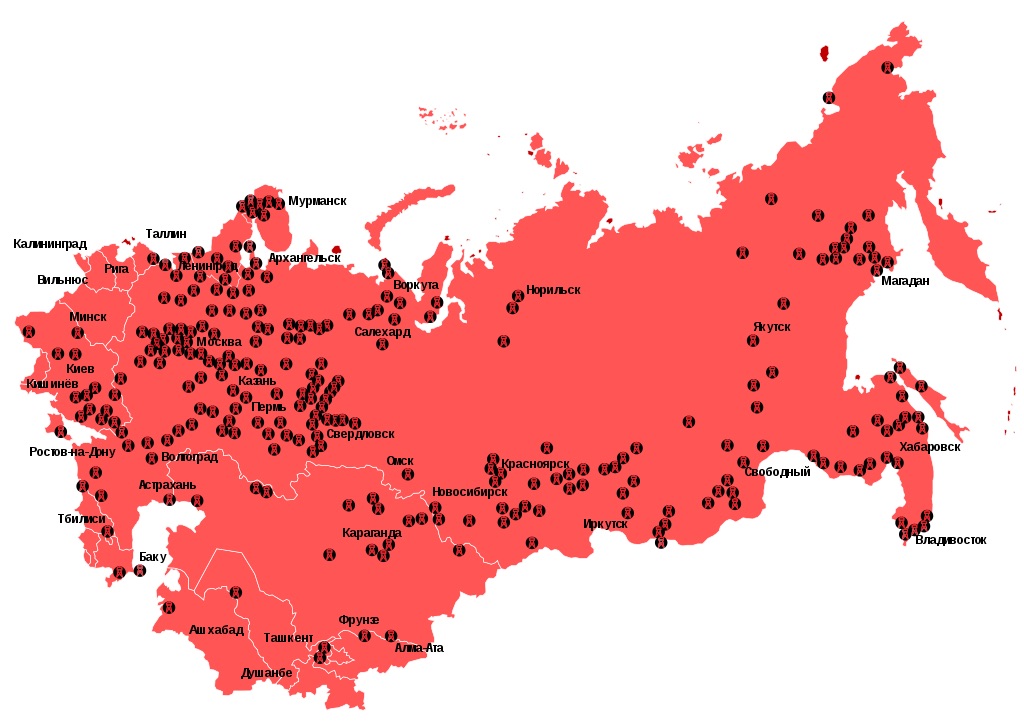

A map showing the location of Gulags created from data provided by the organization Memorial.

Under Stalin the Gulag system, as it came to be known according to the acronym for “Main Administration of Labor Camps,” held millions of prisoners across the entire Soviet Union, prisoners who built their own camps, mined gold and other minerals, and harvested timber, who spoke their own, camp language, and endured humiliation and torture at the hands of their guards. Solzhenitsyn’s notion was that although each labor camp had slightly different conditions, together they represented a second country superimposed on the Soviet empire, an “archipelago” in which each camp was an island unto itself, and yet they all operated according to the same set of violent and inhumane regulations.

In Gulag Archipelago Solzhenitsyn estimated the numbers of victims to be far higher than now attested. He blamed Stalin and the Stalinist system for the deaths of at least 60 million people: 20 million during the forced collectivization of agriculture that resulted in severe famine, 20 million during World War II, and 20 million in Soviet labor camps. Statistics compiled after 1989 by the organization Memorial, however, total 1.6 million deaths in the camps.

Under Stalin the Gulag system held millions of prisoners across the Soviet Union. Here, prisoners work to build a canal connecting the White Sea in the Arctic Ocean with Lake Onega, a project which by itself would kill tens of thousands of laborers.

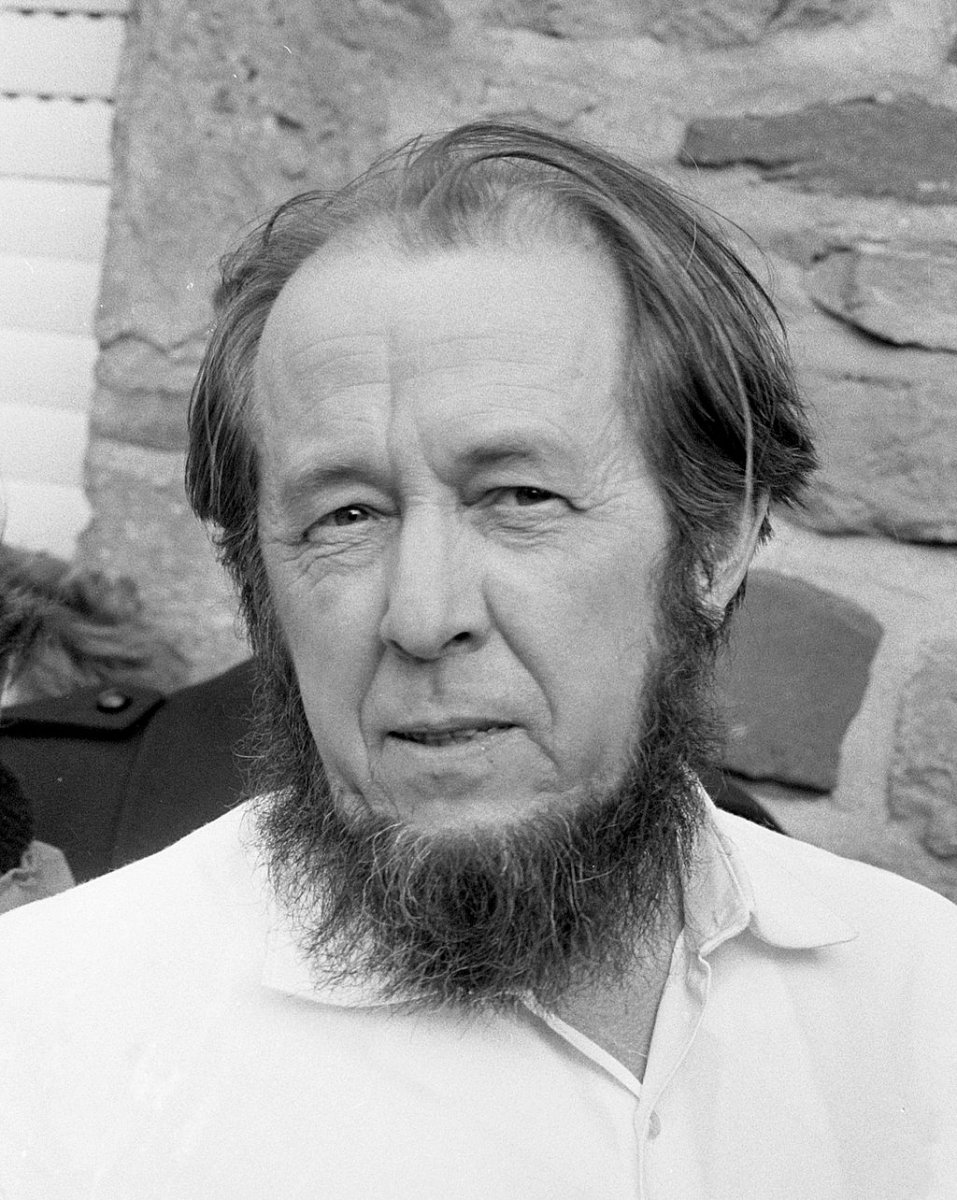

After the publication of the monumental three volume Gulag Archipelago in France in December of 1973, Solzhenitsyn was expelled from the Soviet Union and stripped of his citizenship. In 1974 he was living in exile in Europe and was able to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature in person in Sweden—a prize he had been awarded in 1970, even before the publication of Gulag. His Nobel citation reads: "for the ethical force with which he has pursued the indispensable traditions of Russian literature."

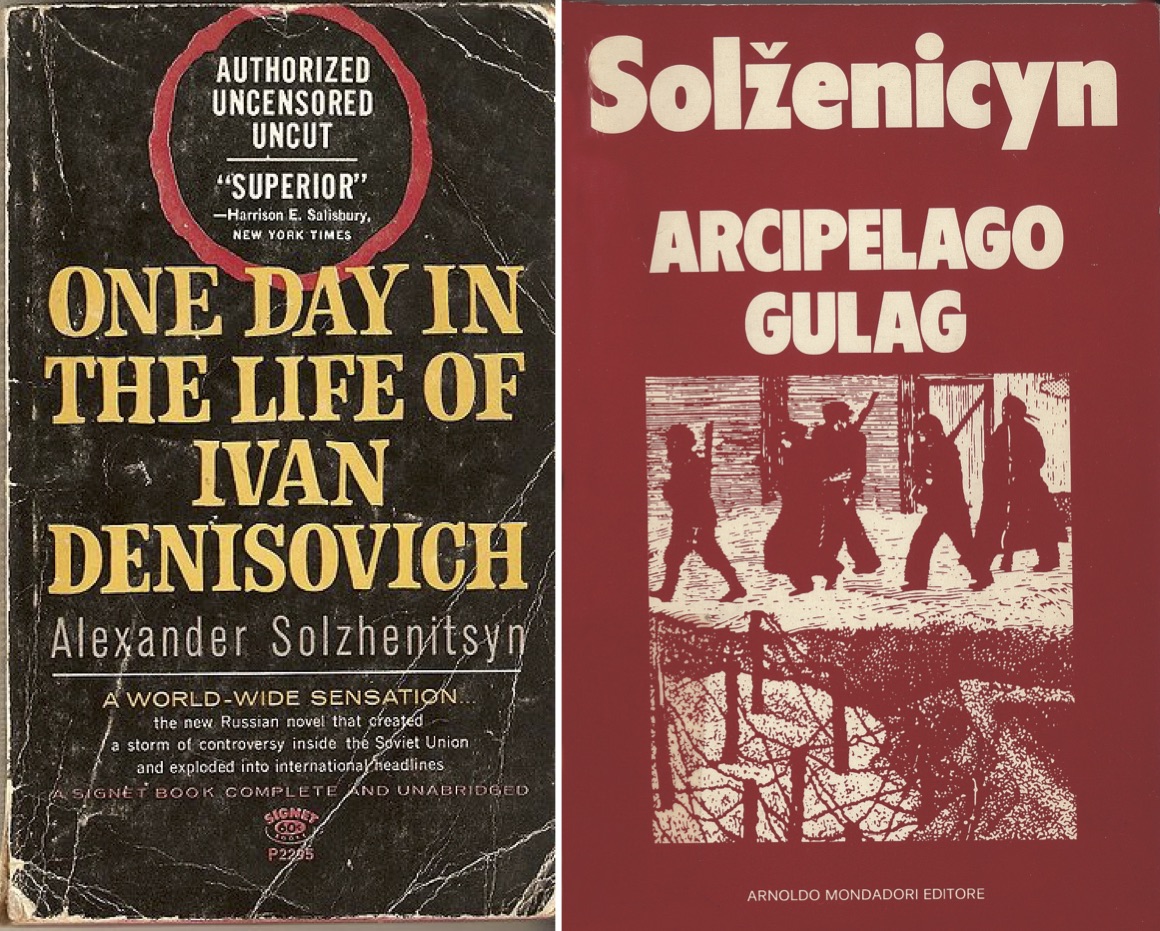

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich was published in the USSR in 1962, but after the publication of the three volume Gulag Archipelago in France in 1973, Solzhenitsyn was expelled from the Soviet Union and stripped of his citizenship.

Solzhenitsyn remained a presence in the West during the Cold War, giving speeches that called for England and the U.S. to recognize and fight the Communist regime in the Soviet Union. He and his family—his second wife, Natalia Dmitrievna and their three sons—moved to Cavendish, Vermont in 1976. While in Vermont he continued to work on his cycle of historical novels, entitled The Red Wheel, which he believed would explain to the world what had happened to Russia in the twentieth century.

Alexander Solzhenitsyn in 1974, after the publication of his famous Gulag Archipelago.

Vowing that he would not return home until his works could be published there, Solzhenitsyn discovered by 1994 that the Soviet Union was history and that there were no longer any barriers to his physical return or the return of his books. He came home in a triumphal procession by train across the entire country, from Vladivostok back to Moscow. By the late nineties, however, his relevance had waned, and his dream of becoming an influential socio-political figure faded.

In his last years, he was fêted by the Russian government, awarded the State Prize of the Russian Federation in 2007 and congratulated personally by Vladimir Putin. He died and was buried with full religious and military honors in 2008 in the Donskoi Monastery cemetery in Moscow. President Dmitry Medvedev attended his funeral. Solzhenitsyn’s chosen status as conscience of his country has been exploited in full by the current Russian state.

Russian President Vladimir Putin congratulating Solzhenitsyn in June 2007; in his last years, Solzhenitsyn was fêted by the Russian government, and even awarded the State Prize of the Russian Federation.

But despite the complicated political part Solzhenitsyn played after returning to Russia in the 1990s, his role as dissident and witness to the horrors of the repressive Soviet regime and his unique literary talents made an indelible mark on twentieth century history.

Scholars and students continue to marvel at the power of his writing, his linguistic innovations, including an expansion of the literary language to include Gulag and other non-standard vocabulary and syntax, and the role Solzhenitsyn played in writing the history of Soviet totalitarianism. A number of his stories, including One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich and the powerful “Matryona’s Home,” remain necessary reading to understand the Russian 20th century.