On December 2, 1980, four churchwomen—Maryknoll Sisters Maura Clarke and Ita Ford, Ursuline Sister Dorothy Kazel, and lay missionary Jean Donovan—became victims of escalating violence toward church members who sided with the poor in El Salvador.

The slogan, Haz patria, mata un cura (“Be a patriot, kill a priest”) became a battle cry for Salvadoran right-wing extremists who believed that anyone who opposed the military regime was a communist, including religious figures.

This slogan, however, targeted more than priests. The murder of the four American churchwomen illustrates the possible fate of those who belonged to the “subversive church.”

Sister Ita Ford with children. Image courtesy of the Maryknoll Sisters. Published with Permission.

The subversive church, according to the Salvadoran military, were those who sided with the poor. A month before her death, Ita Ford told an interviewer, “The colonel of the local regiment [Ricardo Augusto Peña Arbaiza] said to me the other day that the church is indirectly subversive because it is on the side of the weak… The governments find this difficult to handle. It’s very contradictory to their National Security ideology.”

This change in the church became known as Liberation Theology and it would shake the foundation that maintained unequal power relations in countries like El Salvador.

In 1968, Latin American Bishops gathered in Medellín, Colombia to establish a doctrine that would serve poor and oppressed communities: liberation theology. While historically the Catholic Church allied with elites and helped maintain its power over the region, this gathering served as a catalyst for change in peasant communities throughout Latin America. The bishops labeled poverty, injustice, and oppression of marginalized communities in the region as social sins.

The church, according to leading liberation theologists like Gustavo Gutierrez, had a moral responsibility to recognize, understand, and change the social and political realities of Latin Americans: political corruption, state-sponsored violence, and U.S. intervention.

This challenge to the status quo became a threat not only to the Salvadoran government but also to the United States. After the Sandinista victory in Nicaragua in 1979, El Salvador became ground zero for containing communist threats in the western hemisphere.

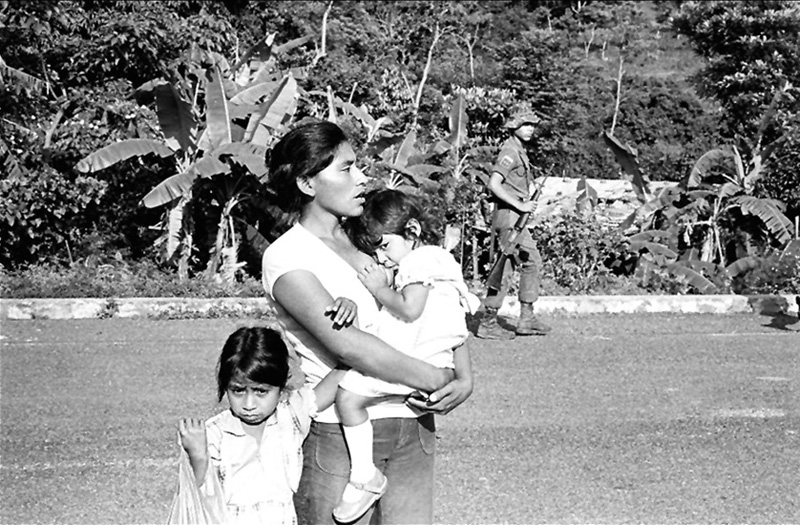

For more than a decade, civil war wracked the country. The U.S.-backed military regime in El Salvador labeled anyone who participated in labor unions, student protests, or Christian base communities (autonomous communities of faith that interpreted the Bible to understand their social reality) as communists insurgents, regardless of whether they subscribed to liberation theology. As a threat to the social order, these individuals and entire communities became victims of state-sponsored violence.

Before their murder, Clarke, Ford, Kazel, and Donovan became witnesses to the violent repression against Salvadoran peasants and workers. While their initial mission was to evangelize and teach Salvadorans how to be better Catholics, their time in El Salvador (and elsewhere in Latin America for Clarke and Ford), led them to see their work as “accompaniment,” the liberation theology model of solidarity that involves living with, supporting, and following the lead of marginalized communities..

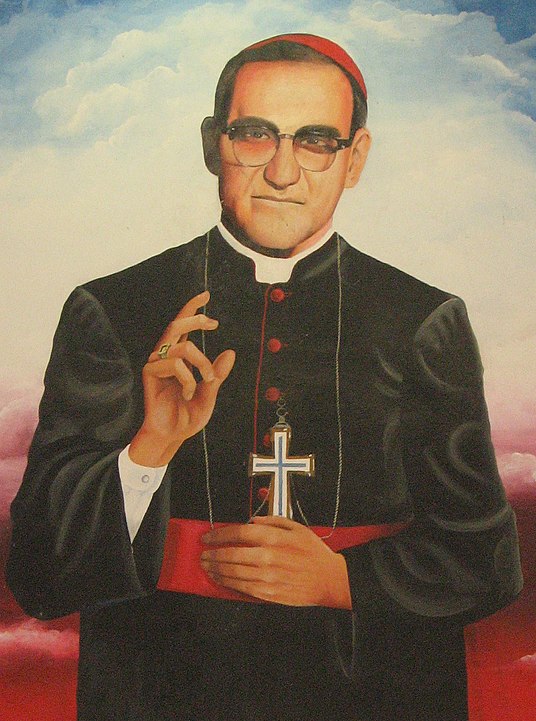

Following the example of Archbishop Oscar Romero, who was assassinated by the Salvadoran military for speaking up for marginalized communities, Clarke, Donovan, Ford, and Kazel worked to “address the cause of the poor as well as their needs.” Their dedication to the people kept them in El Salvador despite the looming threats that they too could become victims of violence.

A mural located at the University of El Salvador bears the image of Archbishop Oscar Arnulfo Romero.

On October 3, 1980, Kazel explained to a friend that despite the danger of repression, she would stay in El Salvador: “We wouldn’t want to just run out on the people.” Similarly, Donovan wrote, “Several times I have decided to leave El Salvador. I almost could except for the children, the poor bruised victims of this insanity. Who would care for them? Whose heart would be so staunch as to favor the reasonable thing in a sea of their tears and helplessness. Not mine, dear friend, not mine.”

As Maryknoll nuns, Clarke and Ford believed that their obligation to denounce injustices in society was far greater than the fear of persecution. They believed in the words of Archbishop Romero when he said, “Christ invites us not to fear persecution because, believe me, brothers and sisters, the one who is committed to the poor must run the same fate as the poor, and in El Salvador we know what the fate of the poor signifies: to disappear, be tortured, to be held captive - and to be found dead.”

On December 2, 1980, Clarke and Ford returned to El Salvador from a regional Maryknoll meeting in Nicaragua. Picked up at the airport by Kazel and Donovan, the women faced an incredibly brutal fate.

For two days no one knew where they were. When U.S. Ambassador, Robert White reported the disappearance of the four churchwomen to the Salvadoran Defense Minister, General José Guillermo García, the General asked if they were wearing habits. In an interview, White recounted that at that moment he knew the women were murdered, because the Salvadoran army would distinguish “good” nuns from “bad” nuns based on their dress code.

On December 4, their bodies were found in shallow graves. They had been raped and shot at close range.

News of the four churchwomen’s murder made its way to the United States but even there, the dichotomy of the good/bad nun prevailed. Because Clarke, Donovan, Ford, and Kazel worked with refugees and poor communities in El Salvador, both the Salvadoran and U.S. government saw them as subversive.

President Jimmy Carter suspended aid to El Salvador because of the murders, but the new Reagan administration publicly called it a mistake. Reagan’s Ambassador to the United Nations, Jeane Kirkpatrick questioned the nun’s motives and believed that the Salvadoran army was not responsible for their murder.

“The nuns were not just nuns,” she claimed. “They were political activists on behalf of the Frente [the Salvadoran guerrillas].”

The murder of the four churchwomen became symbolic of resistance but also of misguidedness. For liberal Catholics in the U.S. and El Salvador, their death became a call to continue fighting against the repressive government in El Salvador while critiquing U.S. foreign policy to the country. On the other hand, for conservative Catholics the murders made sense: working with and under communism would eventually lead to human rights violations.

In 1984, five Salvadorean national guardsmen were convicted for the murder of the four churchwomen. More than 30 years later, the two-highest-ranking military officials at the time were deported from the United States back to El Salvador after linking them to human rights violations. Yet, they have not stood trial in El Salvador for any of their actions during the war, including the events of December 2, 1980.

The recent conviction by Spanish courts of a Salvadorean military officer responsible for the death of six Jesuit priests, their housekeeper, and her daughter, is a promising sign that legal repercussions might still be coming for those responsible for the 1980 killings.

But much work still needs to be done: the current Salvadoran government has taken steps to impede the investigation of the 1981 El Mozote massacre and has sought to pass another general amnesty for all crimes committed during the 1980-1992 civil war.

A mural of the "four churchwomen" in San Salvador, El Salvador. (Image by Alison McKellar).

Despite the divisiveness that their murders created in the U.S. and El Salvador, the four churchwomen are still remembered for their work in Chalatenango and La Libertad, the communities in which they served in El Salvador. Salvadorans have painted murals of them across the country and each year in Chalatenango, a mass is dedicated to the churchwomen.

The life and work of Maura Clarke, Jean Donovan, Ita Ford, and Dorothy Kazel serve as inspiration for Catholics and non-Catholics alike to denounce U.S. imperialism and challenge oppressive structures at home and abroad.