At the very moment when the British people are struggling to cope with the uncertainties caused by their vote for Brexit, we note the anniversary of the Battle of Hastings, which took place on October 14, 1066, 950 years ago. This invasion from across the English Channel resulted in the conquest of Anglo-Saxon England by William, the French Duke of Normandy. It is a reminder that the complicated, ambivalent, and sometimes hostile relationship between England and the rest of Europe goes back a long way.

|

In January 1066, Edward the Confessor, King of England, died without an heir, which motivated several claimants to the English throne to begin a struggle for succession. The Anglo-Saxon Witenagemot (a council of Anglo-Saxon wise men) gave its consent to Harold Godwinson, the brother–in-law of Edward and the most prominent nobleman of the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom, to inherit the crown.

William, Duke of Normandy, and Harald Hardarda, King of Norway, however, immediately challenged the new king. William hinted that Edward had promised the crown to him, while Harald said much the same.

The Norwegian King invaded northern England in September 1066, but was defeated and ultimately killed by Harold in the Battle of Stamford Bridge on September 25. Three days later, William, Duke of Normandy, landed his fleet in the south of England at Pevensey, which forced Harold to rush back from the North. They met at Hastings on October 14.

The Norman cavalry with its new equipment and techniques attacked English warriors armed with traditional battleaxes. William’s knights defeated the English army and killed King Harold. The victory enabled William to establish and consolidate his Norman-English Kingdom. Importantly, though, the Norman Conquest gave England a dual identity: an English kingdom standing on its own, and a part of the Norman Dukedom subjugated to the French monarchy.

Was William’s claim to the English throne legitimate? In the eleventh century, both the Christian law of marriage and the secular law of primogeniture were not firmly established. Therefore, neither Harold, nor William, nor Harald could make a convincing claim based on those principles. Instead, a crown was regarded as belonging to an individual king, who might bestow it on someone of his choosing, though that risked angering his subjects.

Therefore, William actually legitimized his English crown on the bases of a battlefield victory and a successful occupation thereafter. This customary principle eventually functioned to settle European internal land or territory disputes during the Middle Ages, and continued well after that as well.

William I "The Conqueror," Norman King of England

After the Norman Conquest, it took William I his remaining years to suppress local resistance. Many Anglo-Saxons resettled in Scotland, Ireland, Scandinavia, and even as far away as the Black Sea coast. The Norman kind implanted a feudal structure in England, enabling the Norman noblemen and knights to seize most landed estates.

He demanded a loyalty oath from his subjects and conducted a comprehensive land survey, which was recorded in the Domesday Book. This, in turn, increased royal revenue and helped William I turn England into a much more centralized kingdom than most of the continental kingdoms with a multi-ethnic population at the time.

Some older Anglo-Saxon institutions were preserved and continued to function. The traditional Witenagemot was gradually transformed into the Royal Council and ultimately gave the birth to English parliament. The sheriffs continued to manage local administrations on the king’s behalf and the county courts were preserved for settling local legal disputes by ever-more standardized royal writs. And the Anglo-Saxon customary laws, with jury trial as its most impressive mechanism, were preserved and expanded into a system of common law.

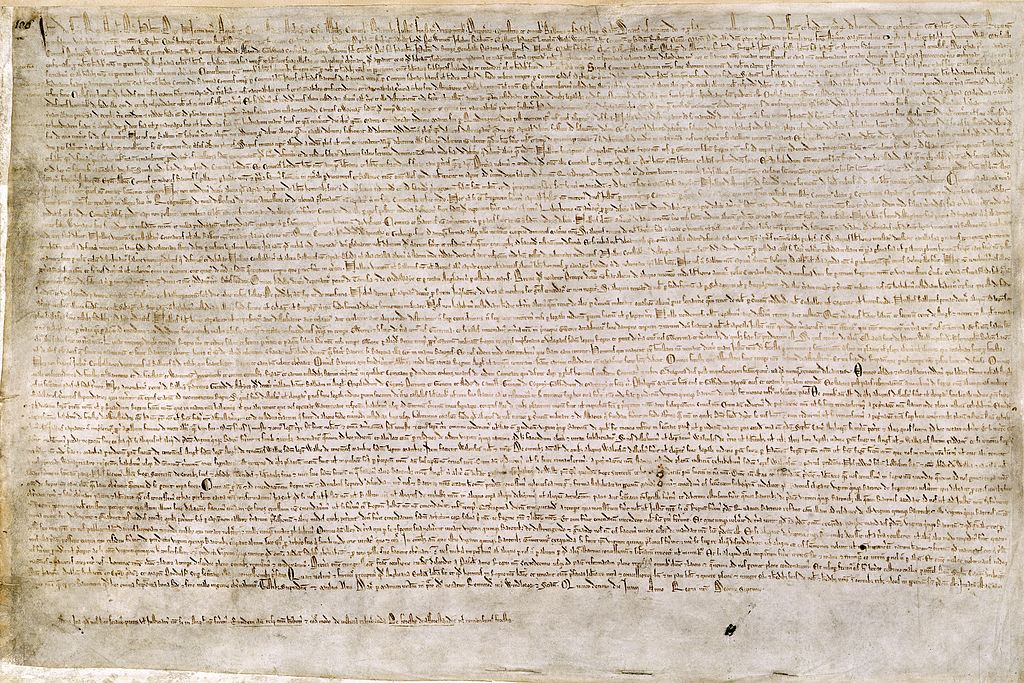

Most of all, the combination of the continental feudal practices and the English common law customs helped England to invent and produce a unique constitutional document, Magna Carta, to balance the king’s privileges and subjects’ liberties in 1215.

One of four known copies of the 1215 Magna Carta.

Therefore, a pluralistic English nationhood was an unanticipated consequence of the Norman Conquest. Today, the vote for Brexit indicates that the English people are troubled by the growing numbers of immigrants from Eastern Europe and from Islamic countries. They are soon going to face a choice between reconstructing their nationhood of the twenty-first century on the basis of small-minded nativism or a more cosmopolitan, pluralistic integration.

Nine hundred and fifty years after the Normans invaded and tied England to the Continent, Britain voted to leave the European Union. Simultaneously, Londoners elected Sadiq Khan, a Muslim Englishman of Pakistani descent, to be mayor of London in May, 2016. The world does not expect twenty-first century England to go back to the so-called “Splendid Isolation,” but to continue its role of contributing gloriously its wisdom and strength to European growth and world peace.