For most of 2022 and into 2023, the people of El Salvador have been living under a form of martial law called a “state of exception.” That phrase is almost ironic because as historian Stephanie Huezo explains, El Salvadorans have endured one form of military or authoritarian government for much of the last century. And again this time, El Salvador's poor and its youth have been most affected by it.

In early December 2022, the Salvadoran government approved its ninth extension of the country’s “state of exception.” Since March 2022, this state of exception has restricted a wide range of civil liberties protected by the constitution in order to prioritize a crackdown on gang activity and violence.

While President Nayib Bukele and the National Police reported very few homicides during these months, and while a majority of members of the legislative assembly voted for the extension, average citizens with no connection to crime have become victims of this policy—especially poor and young people.

Roughly 60,000 Salvadorans have been arrested for suspected gang violence by the National Police and the Armed Forces, sometimes without evidence. Reports of young men detained without explanation at their homes, at work, or in the streets have appeared in national and international news reports, in social media, and in everyday conversations. Despite the arbitrary nature of this policing, those arrested may be imprisoned for up to six months before appearing in court.

Sensational images of these arrests pervade social media, particularly from official accounts of the National Police Force and the Salvadoran Armed Forces. Photographs of detainees’ tattoos are highlighted to demonstrate affiliation with MS-13 or Barrio 18, the two largest gangs in El Salvador.

On Twitter, these images are accompanied by #guerracontrapandilla (#waragainstgangs) and #seguimos (#wecontinue) to express the urgency of the Bukele Administration’s actions.

These images have helped convince neighboring Honduras to declare a similar state of exception. But while purportedly validating the anti-gang measures that abridge constitutional rights, the campaign also contributes to the rise of authoritarianism—militarized repression and state surveillance—especially in poorer communities.

Authoritarianism, the use of militarization for territorial control, and the targeting of the poor and youth are nothing new in El Salvador.

Critics of Bukele’s administration note the country’s history of authoritarian leadership and point to government policies that have long exposed young and poor/working-class communities to violence and human rights abuses.

The Salvadoran people deserve to live in a safe country. Indeed, the current administration has lowered the homicide rate. At the same time, this safety comes through what one community leader calls “poniendo el dedo” (falsely incriminating someone). The current administration has created conditions that harken back to earlier authoritarian eras in El Salvador.

Militarization in El Salvador

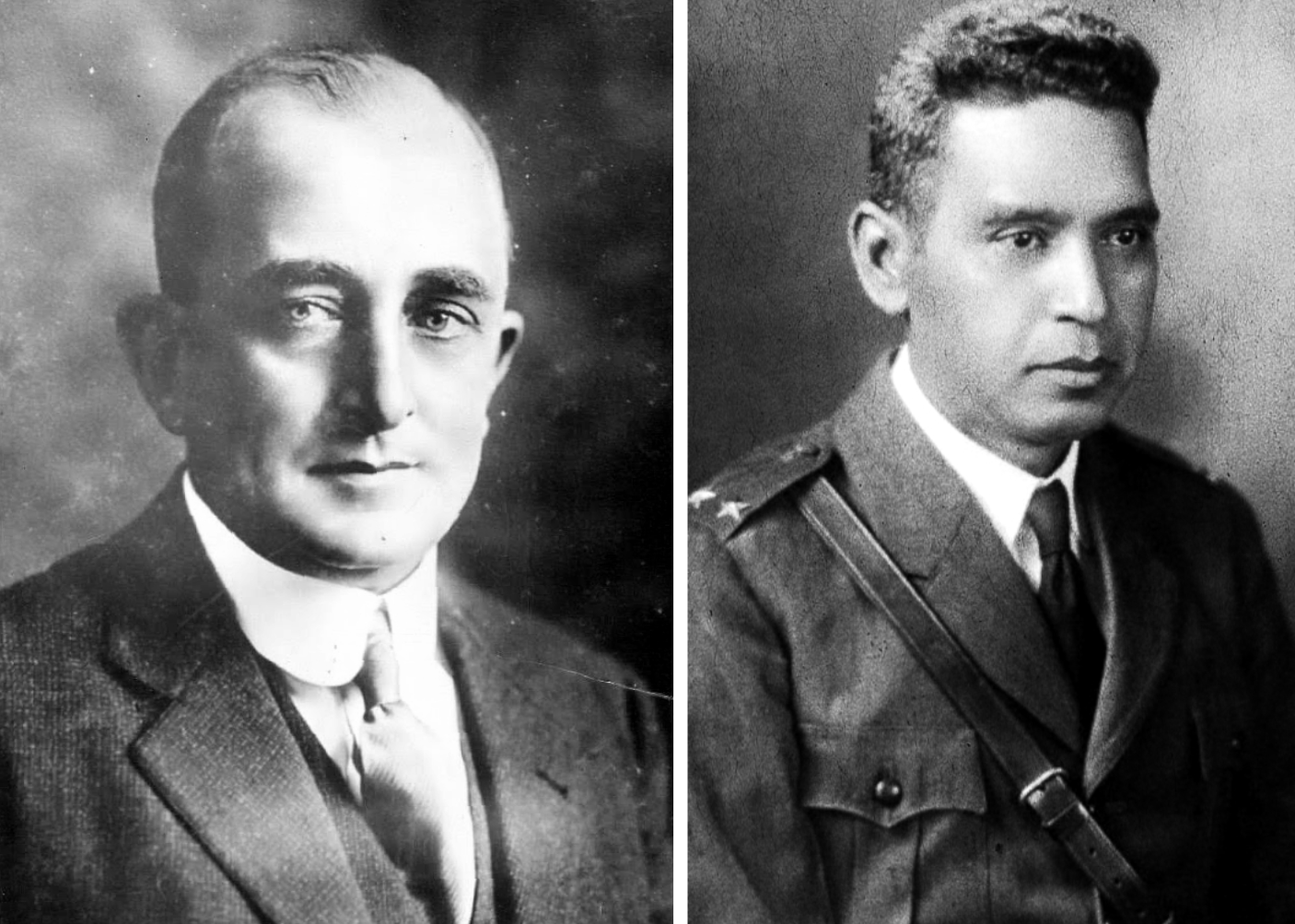

Historians have marked the early 20th century in El Salvador as the pinnacle of militarization, when the military focused more on controlling its citizens than defending them from external attacks. While the country democratically elected a reformist president, Arturo Araujo, in 1931, a military coup ousted him after less than nine months.

As a result, General Maximiliano Hernández Martínez became president and reinforced state control with military force. The following year, he wielded this power by slaughtering participants in a peasant and indigenous uprising.

In January 1932, amid the global economic depression, peasant and indigenous communities in Western El Salvador rose up against local governments to demand better living and working conditions. Armed with machetes, sticks, and rocks, the rebels attacked the haciendas of well-known landowners and military garrisons. They gained control over some territories including Izalco, Nahuizalco, and Juayua—historically indigenous areas.

But the government reacted quickly. To protect the land and property of the coffee-growing elites, military forces prioritized reclaiming occupied territories. They also used civilian patrols, composed of mainly ladinos (non-indigenous people), to round up those suspected of rebellion.

According to interviews with witnesses who lived in Nahuizalco at the time, as reported in the documentary La Palabra en el Bosque/Scars of Memory, virtually every male over the age of twelve was killed. After two weeks, the military had indiscriminately murdered between 10,000 and 40,000 Salvadorans. This watershed event is known as La Matanza (the 1932 Massacre).

General Maximiliano Hernández Martínez continued to hold power for another twelve years, followed by more than three decades of continued military alliance with the elites, the longest run of uninterrupted military rule in El Salvador (1932-1979).

Military leaders used their power, while some implemented reformist projects to quell social uprisings. Despite reformist moves, the military party sustained authoritarian rule by monopolizing the executive branch, the legislative assembly, and municipal governments.

During this time of authoritarianism, popular discontent swelled. In 1944, after the legislative assembly of Hernández Martínez amended the constitution to allow the dictator to serve a fourth consecutive term, urban workers, schoolteachers, students, and even economic elites and young military officers united to overthrow him.

While the coup failed, the opposition changed its strategy and held a strike known as the Huelga de Brazos Caídos (Fallen Arms Strike). Workers stopped working, and teachers and students stayed home from school throughout cities in El Salvador. The strike lasted a month.

Though this effort succeeded in ousting the dictator, it did not grow into a sustainable civic coalition. Five months after the coup, conservative military officials led a countercoup. They used their new powers to repress and dismantle civic organizations. This pattern continued until the beginning of the civil war in 1980.

Discontent Grows

Young people, especially university students, and poor rural communities actively expressed their discontent throughout the second half of the 20th century.

For example, in 1960, under President José María Lemus, the National Police and National Guard entered the University of El Salvador, claiming it to be a breeding ground for anti-state subversion, or communism. Students and staff were beaten and incarcerated, and one student, Mauricio Esquivel Salguero, was beaten to death. After these events, the university shut down until after a successful coup against Lemus.

Despite the change in leader, and a short-lived mini opening for democracy, repression against university students continued. In 1968, after the implementation of educational reform, students supported teachers in their opposition to the reform as well as for better working conditions.

The violence toward students peaked with the 1975 University of El Salvador Student Massacre. On July 30, after a military invasion of the campus five days earlier, the military violently ended a peaceful march calling for autonomy from the Salvadoran government. The exact number of victims of the student massacre remains unknown, but state forces murdered at least 100 students, teachers, and staff.

Universities weren’t the only targets of violence.

In rural El Salvador, labor organizers also received the brunt of state sanctioned violence. Peasant leaders worked closely with the Catholic Church to raise consciousness of their maltreatment by large landowners and the Salvadoran state.

Sectors of the Catholic Church, inspired by Liberation Theology, created programs that offered peasants a space to question the condition of their lives, and, at times, to take a step toward seeking justice.

For example, members of a Christian Base Community group, which read the Bible through a critical lens, participated in local political organizations and movements, like a six-hour peaceful strike by 1,600 workers in La Cabaña Sugar Mill. This new political awareness also led many campesinos to help form labor organizations such as the Union of Rural Workers (Union de Trabajadores Campesinos, UTC) in 1974 in Chalatenango and San Vicente.

Because of this new challenge to large landowners and the Salvadoran state, peasant leaders were persecuted and eventually became victims of full-scale military operations. One of the earliest mass targetings of peasant leaders occurred in a small town called La Cayetana. The National Guard surrounded the town and murdered six farmworkers for their alleged connection to labor organizing in 1974.

While peasant leaders had been targeted before, the La Cayetana Massacre was seen to be the first to involve the whole community. Despite the violence toward peasant leaders and their communities, massacres like La Cayetana pushed peasants to organize as a form of protection.

Due to increased organizing, the National Guard expanded its presence in rural communities to spy on peasant leaders.

The National Democratic Organization (ORDEN) recruited civilians to keep order in their communities. Peasants joined ORDEN because it offered opportunities otherwise unavailable, like healthcare and promises of land. Being a member of ORDEN also protected them from state-sanctioned violence.

Amidst the growing politicization of peasants, ORDEN served to prevent uprisings of workers. It tasked residents to monitor their own communities, report suspicious activity, and at times even torture neighbors suspected of organizing against the government. This culture of fear and violence permeated throughout the 1970s and continued through the civil war in El Salvador (1980-1992).

Some peasants not associated with ORDEN also began to spy on their neighbors and report any “subversion” to authorities. These individuals were known as orejas (the ears). Arbitrary detentions, kidnappings, and murders of the supposed “internal enemy” were common during the war and poor and rural communities were the most targeted.

Criminalization of Poverty and Youth

Because landless peasants and indigenous communities rose up to demand better working conditions and fair wages, the government often characterized them as communists. This perception in turn led to the massacre of thousands of indigenous and peasant people.

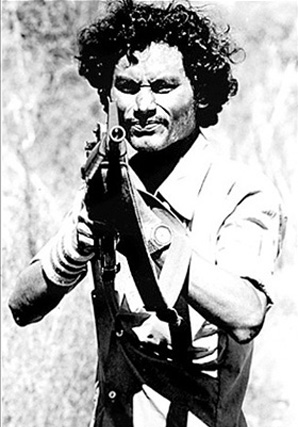

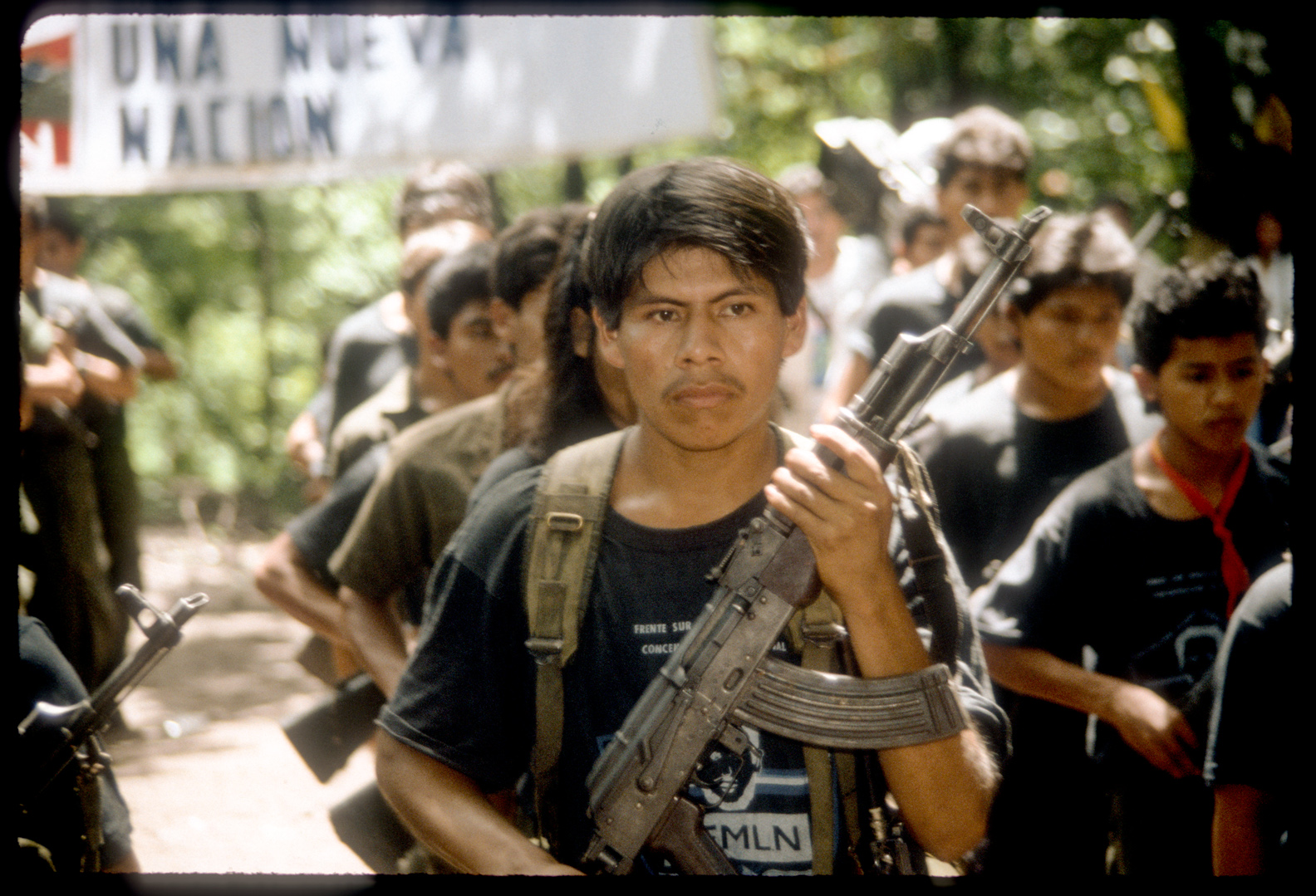

Similarly, during the civil war between the military government and the leftist guerilla group, the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN), the Salvadoran state suspected the rural poor of collaborating with the guerrilla movement because the FMLN had promised to topple any government that suppressed these communities.

The war was a national liberation struggle against wealth and land inequality, but because it sought to dismantle the status quo, the military government painted it as subversive.

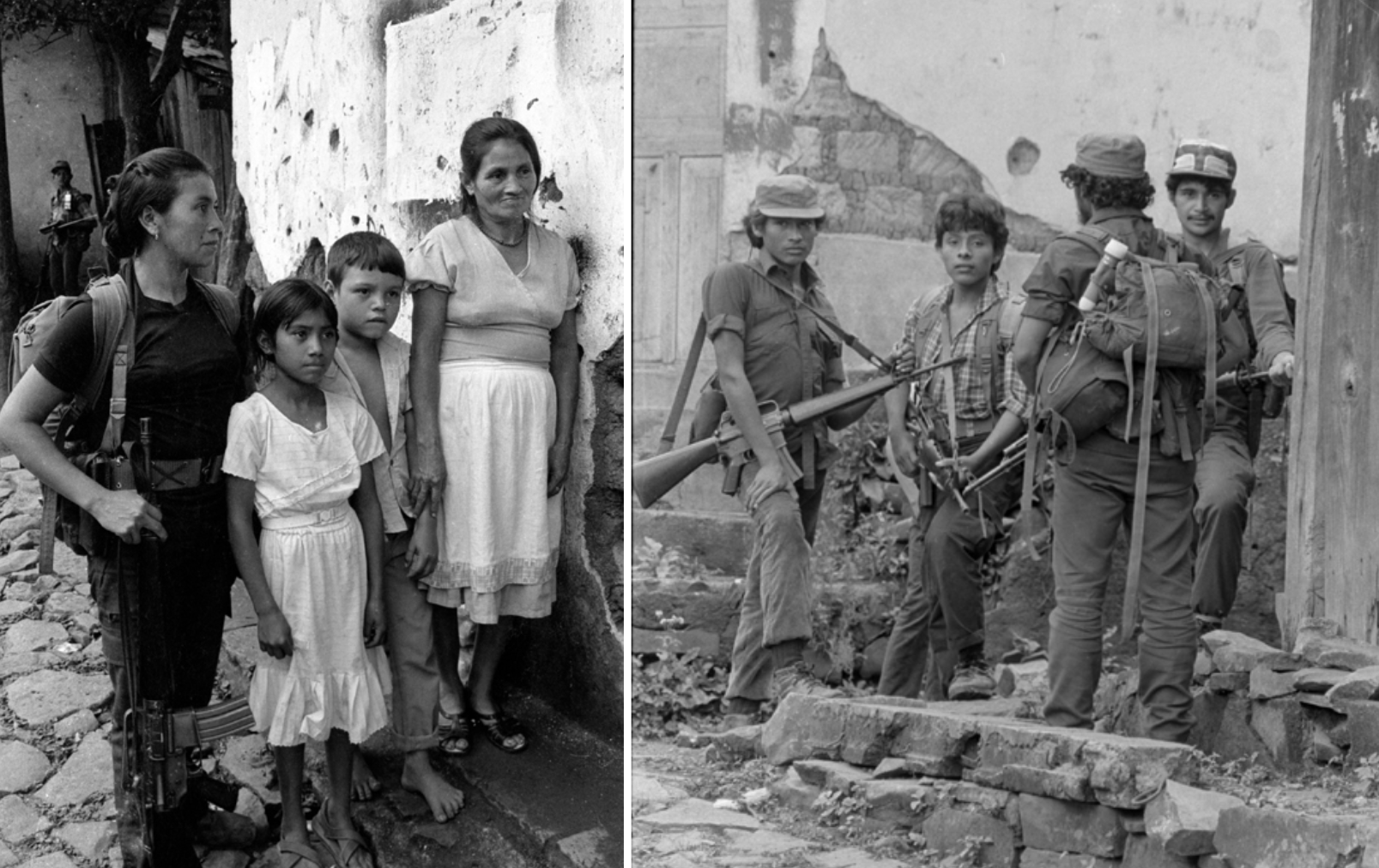

During the civil war, rural and poor youth were two of the most vulnerable populations. Whether victims of murder, or forcefully recruited to join the Salvadoran army, youth became targets of violence.

In 1981, the Atlácatl Battalion, a U.S.-trained special forces unit, entered El Mozote in Morazán and raped, tortured, and murdered men, women, and children for suspected guerrilla activities. According to testimonies after the massacre, the common soldiers’ saying “one dead child, one less guerrilla” was written in blood in a house nearby.

The report of the Truth Commission, published in 1993, stated that the majority of the victims of such gruesome acts were minors.

Aside from being victims of murder, about 80% of the Salvadoran army and 20% of the FMLN were under 18 years old. Both organizations recruited youth, but the Salvadoran army also abducted them. Such actions virtually ensured that people would resort to subversive activities.

Even after the signing of the Peace Accords in 1992 officially ended the war, youth and rural communities continued to suffer its effects. The demobilization of the FMLN left many peasants, especially those who grew up in guerrilla camps, with few opportunities to improve their lives.

While the peace negotiations included the demilitarization of political life, they did not address the social and economic inequality that caused the civil war to begin with. Emigration after 1992 resulted in the breakdown of family and community structures. Additionally, an unprecedented increase in crime during the 1990s contributed to social disintegration. According to some estimates, postwar criminal violence surpassed the carnage of war.

The state blamed the rise in postwar violence on the emergence of gang culture in El Salvador. The most notable gang, MS-13 (Mara Salvatrucha) emerged in the United States with immigrants fleeing the civil war during the 1980s. Since the U.S. government has denied political asylum or refugee status to Salvadorans, many arrived undocumented and settled in poor and overcrowded parts of Los Angeles.

In Los Angeles some Salvadoran youth joined existing gangs like 18th Street gang or created their own like MS-13 to protect themselves from other ethnic gangs in the city. These were known for petty crime, but with President Ronald Reagan’s escalation of the war on drugs, Salvadoran gang members were imprisoned and deported.

In the face of social abandonment and disintegration, war trauma, and neoliberal policies that prioritized economic growth over social well-being, gang culture in El Salvador became a profound social problem at the end of the millennium.

In 2003, right-wing president Francisco Flores declared a “war on gangs.” Anti-gang policies that soon followed became known as the Mano Dura (Iron Fist). Mano Dura allowed for the immediate imprisonment of suspected gang members and longer prison sentences. These individuals were mostly young men with certain characteristics. Tattoos, hand signs, and other fashion items associated with gang culture essentially became criminalized. To crack down on gang members, the Salvadoran government sent soldiers to the streets.

Many scholars and activist groups have pointed out that the militarization of the streets violated the 1992 Peace Accords. While the Supreme Court declared these policies unconstitutional, with the election of right-wing president Antonio Saca in 2004, Operation Super Mano Dura continued these anti-gang policies. This time, however, the police had to prove actual criminal behavior to arrest gang members. Still, the criminalization of youth continued.

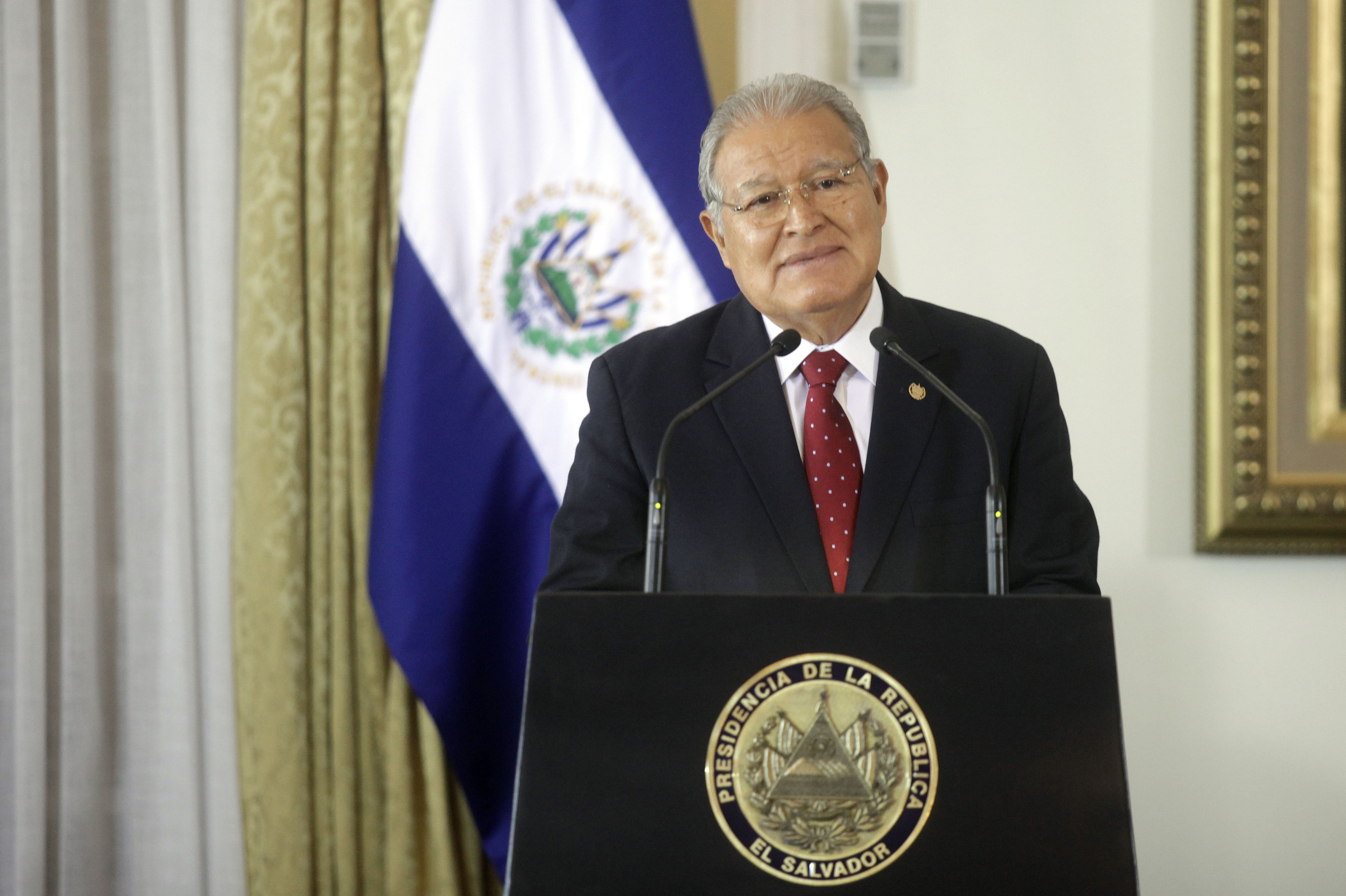

Anti-gang policies weren’t exclusive to right-wing governments. The first left-wing FMLN president, Mauricio Funes (2009-2014), continued the state’s commitment to ridding the country of gang violence. His successor, FMLN president Salvador Sánchez Cerén, followed suit.

At first the Funes administration sought an alternative to anti-gang strategies by focusing on prevention rather than arrests. After an attack on a bus that killed 17 people in 2010, however, he continued certain parts of the Mano Dura strategy.

Three years later Funes sought a truce with MS-13 and 18th Street gangs to lower the homicide rate, but the truce deteriorated rapidly and homicide rates rose again. The police retaliated with extrajudicial executions of suspected gang members.

The “gang problem” that has plagued El Salvador for more than 20 years has criminalized youth regardless of their active or non-existent connection with gangs. Police and military forces have profiled young, poor, and able-bodied Salvadoran men whose bodies might be marked by tattoos, piercings, or certain types of clothing.

The increase in homicide rates gave right-wing, left-wing, and third-party governments like the current Bukele administration justification to increase repressive measures.

Millennial Authoritarianism

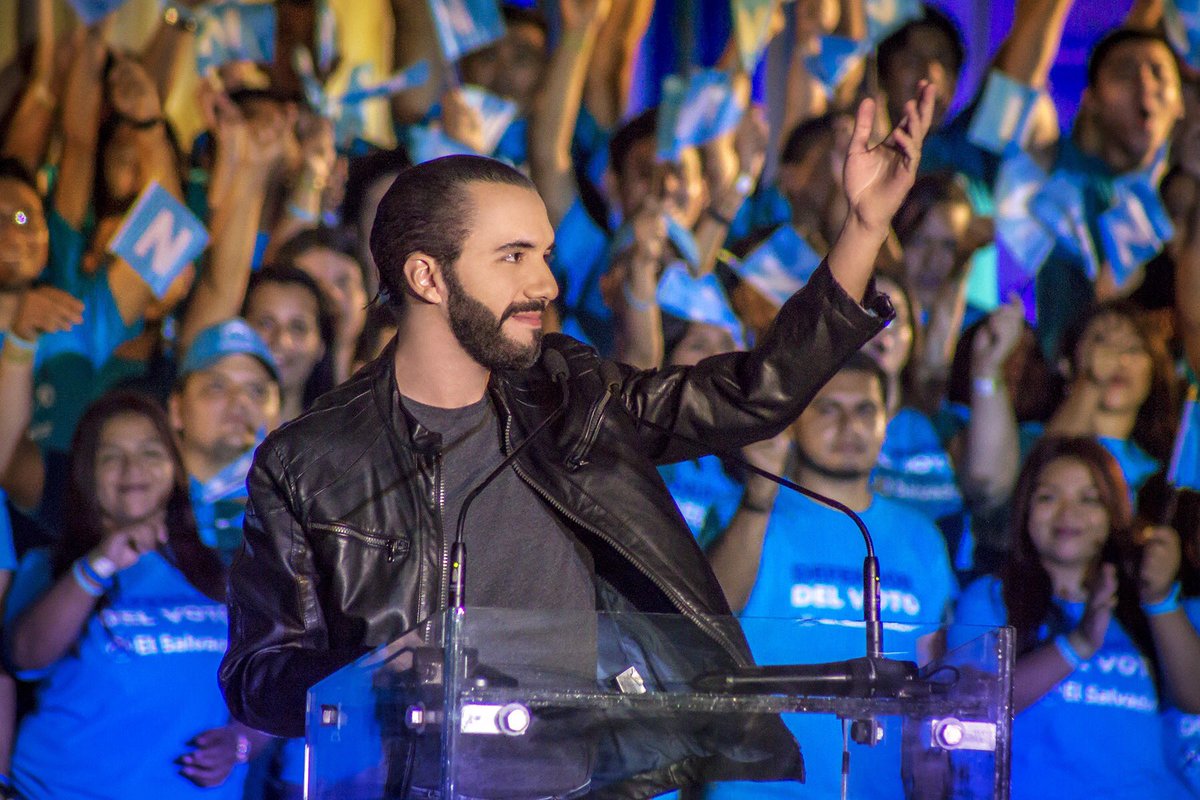

Mistrust of both the right-wing ARENA government and left-wing FMLN government over the handling of gangs, among other issues, pushed many Salvadorans to elect President Nayib Bukele in 2019.

In his rhetoric, Bukele distinguishes himself from the two-party system that governed El Salvador since the end of the civil war by claiming a hard stance on corruption and on anti-gang measures. Yet his approach aligns with previous government measures, and his policies harken back to an authoritarian past.

Days after his inauguration in June 2019, Bukele launched the Territorial Control Plan, a multi-step initiative to combat gang violence and improve security in El Salvador. Although phases one and two were approved by majority vote in the legislative assembly, tensions began to rise when Bukele requested approval of a $109 million loan to fund phase three.

Phase three focused on modernizing the security forces—buying drones, helicopters, and police vehicles and updating uniforms and video surveillance equipment. When members of the Legislative Assembly refused to vote, leaving the voting body without a quorum, Bukele summoned an emergency meeting in February 2020 where armed police and military soldiers occupied the country’s parliament as a show of force. He was quoted as saying, “Now I believe that it’s very clear who has control of the situation.”

Opponents, critics, and human rights organizations have condemned this act and some even called it a coup attempt. Others have referred to this event as a backsliding of democracy and called Bukele a dictator/authoritarian.

Despite opposition, and in face of the COVID-19 pandemic, Bukele continued to use the police and military to control society through anti-gang measures. Arbitrary arrests of people who did not follow COVID-19 restrictions rose. Those arrested were detained in overcrowded, unhygienic conditions likely to spread the disease further.

Human rights organizations criticized Bukele’s approach to the pandemic for the lack of health care, especially to those forcefully quarantined in government-sponsored buildings. Oscar Méndez died in quarantine, and his family has declared it due to medical neglect. Despite criticisms, Bukele continued the state of emergency under the rhetoric of protecting Salvadorans from the pandemic.

Authoritarian tendencies continued even after the fear of the pandemic decreased. A year later, Bukele’s party won a majority of assembly seats, and he consolidated his power by removing and replacing Supreme Court magistrates and the Attorney General. He also made bitcoin legal tender, claiming it would modernize the country’s economy and turn it into a financial hub.

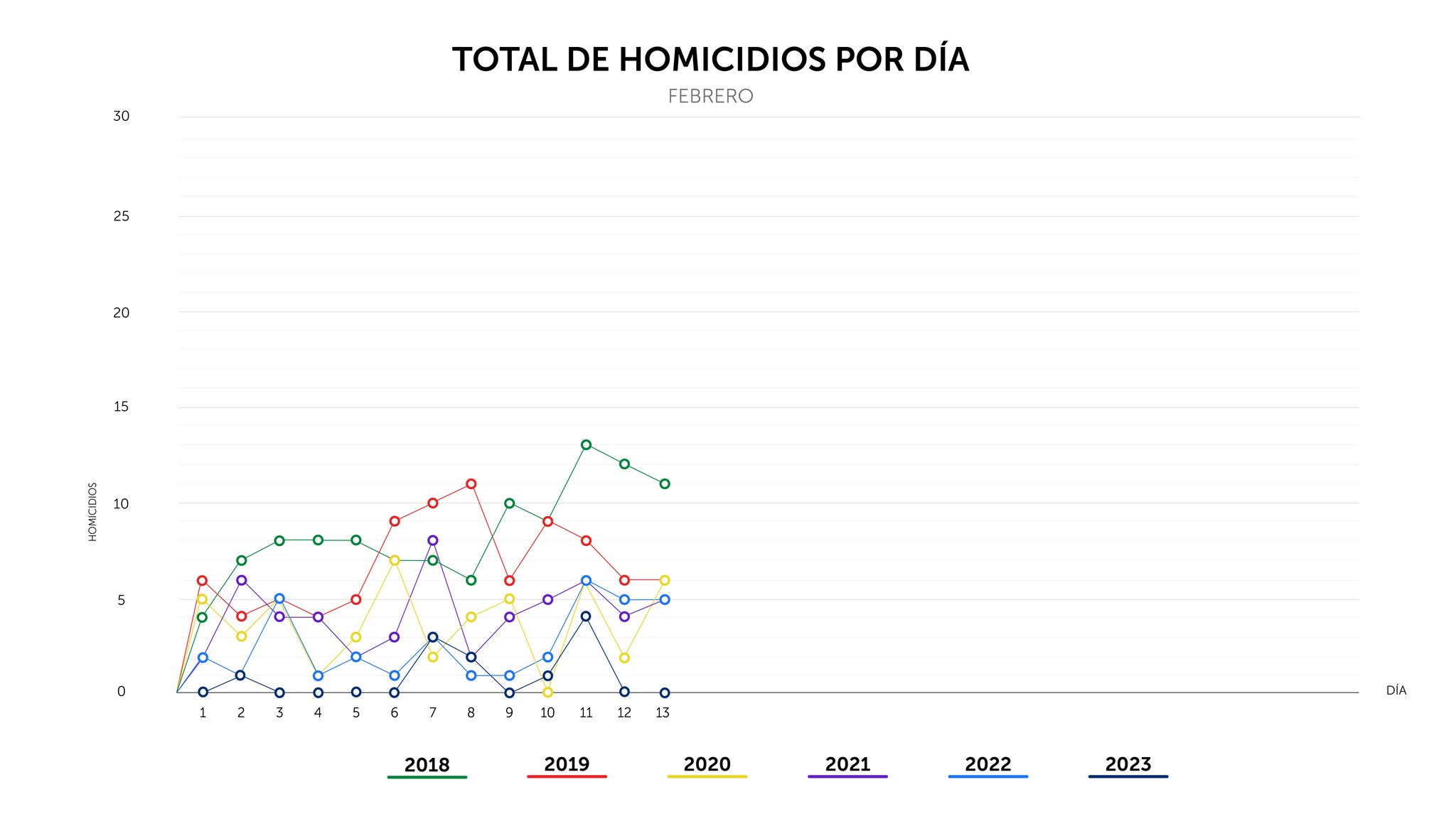

With his party controlling the majority of the Legislative Assembly, Bukele has been able to pass laws and policies without much opposition. So when homicide rates for the month increased drastically in March 2022, Bukele had no opposition to declaring a state of exception that has now been extended nine times.

His policies have not only affected gangs, however. Reports have stated that Bukele’s administration has arrested two percent of its adult population.

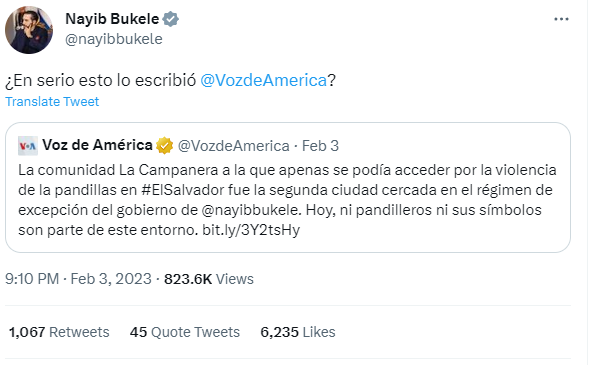

More than 3,000 complaints of human rights abuses have been filed with El Salvador’s Human Rights Ombudsman. Family members have not been able to visit their loved ones, despite pleading with the government. When newspaper outlets report on these abuses, arbitrary arrests, or family pleas, Bukele pushes back on twitter, claiming the reports to be false.

Such actions are not new in El Salvador. From the culture of militarism to the discourse about eliminating the internal enemy, Salvadoran society has long been a victim of state-sanctioned physical, structural, and cultural violence. And the population continues to support Bukele.

Disillusioned with previous governments, Salvadorans saw in Bukele a fresh politician, one who took seriously the safety of the people. And because of this support, Bukele has been able to rationalize power grabbing as representing the people’s desires.

He even announced on September 15, 2022 that he would seek reelection in 2024 despite a constitutional ban against serving consecutive presidential terms.

This move is clearly non-democratic. However, Salvadorans who have not been impacted by the arbitrary arrests of their loved ones continue to wholeheartedly support him because social media and the homicide rates have showcased a safer El Salvador, no matter the cost.

Resistance

Just as patterns of repression have persisted throughout El Salvador’s history, so have patterns of resistance.

Today, identity-based organizations, students, workers, peasants, and others have taken to the streets to denounce the antidemocratic measures of President Bukele.

Mostly organized by the Popular Resistance and Rebellion Bloc (Bloque de Resistencia y Rebeldia Popular, BRP)—a platform that brings together popular movements, social organizations, and trade unions—these protests included demands for the elimination of bitcoin and condemnation of the illegal mass firing of judges, political persecution, militarization, and the potential reelection of Bukele.

Ultimately, these protests sought to prevent the consolidation of Bukele’s dictatorship.

The continuation of popular opposition might slow or prevent the consolidation of power, but such mobilization needs to be sustainable with countrywide political education and organization. With a high popular approval of Bukele in El Salvador and sectors of the Salvadoran diaspora, the resistance movement has a long road ahead.

Abrego, Leisy and Steven Osuna, “The State of Exception: Gangs as a Neoliberal Scapegoat in El Salvador.” Brown Journal of World Affairs. Vol 29, No.1 (Fall/Winter 2022): 59-73.

Almeida, Paul. Waves of Protest: Popular Struggle in El Salvador, 1925-2005. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008.

Chávez, Joaquín Mauricio. Poets and Prophets of the Resistance: Intellectuals and the Origins of El Salvador's Civil War. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Ching, Erik. Authoritarian El Salvador: Politics and the Origins of the Military Regimes, 1880-1940. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2014.

---. Stories of Civil War in El Salvador: A Battle Over Memory. Chapel Hill: North Carolina Press, 2016.

Gould, Jeffrey and Carlos Henríquez Consalvi. Scars of memory. Brooklyn: Icarus Films, 2002.

Gould, Jeffry and Aldo Lauria-Santiago. To Rise in Darkness: Revolution, Repression, and

Memory in El Salvador, 1920-1932. Durham: Duke University Press, 2008.

Hume, Mo. “Mano Dura: El Salvador Responds to Gangs.” Development in Practice. Vol 17, No. 6 (2007): 739-751.

Levenson-Estrada, Deborah. Adiós niño: the gangs of Guatemala City and the politics of death. Durham: Duke University Press, 2013.

Lindo-Fuentes, Héctor, Rafael Lara Martínez, and Erik K. Ching, Remembering a Massacre in El Salvador: The Insurrection of 1932, Roque Dalton, and the Politics of Historical Memory. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2007.

Moodie, Ellen. El Salvador in the Aftermath of Peace: Crime, Uncertainty, and the Transition to Democracy. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012.

Wolf, Sonja. Mano Dura: The Politics of Gang Control in El Salvador. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2017