For a moment, everything seemed possible. From February 22 to 25, 1986, hundreds of thousands of Filipinos gathered on Epifanio de los Santos Avenue to protest President Ferdinand Marcos and his claim that he had won re-election over Corazon Aquino.

Soon, Marcos and his family were forced to abdicate power and leave the Philippines. Many were optimistic that the Philippines, finally rid of the dictator, would adopt policies to address the economic and social inequalities that had only increased under Marcos’s twenty-year rule. This People Power Revolution surprised and inspired anti-authoritarian activists around the world.

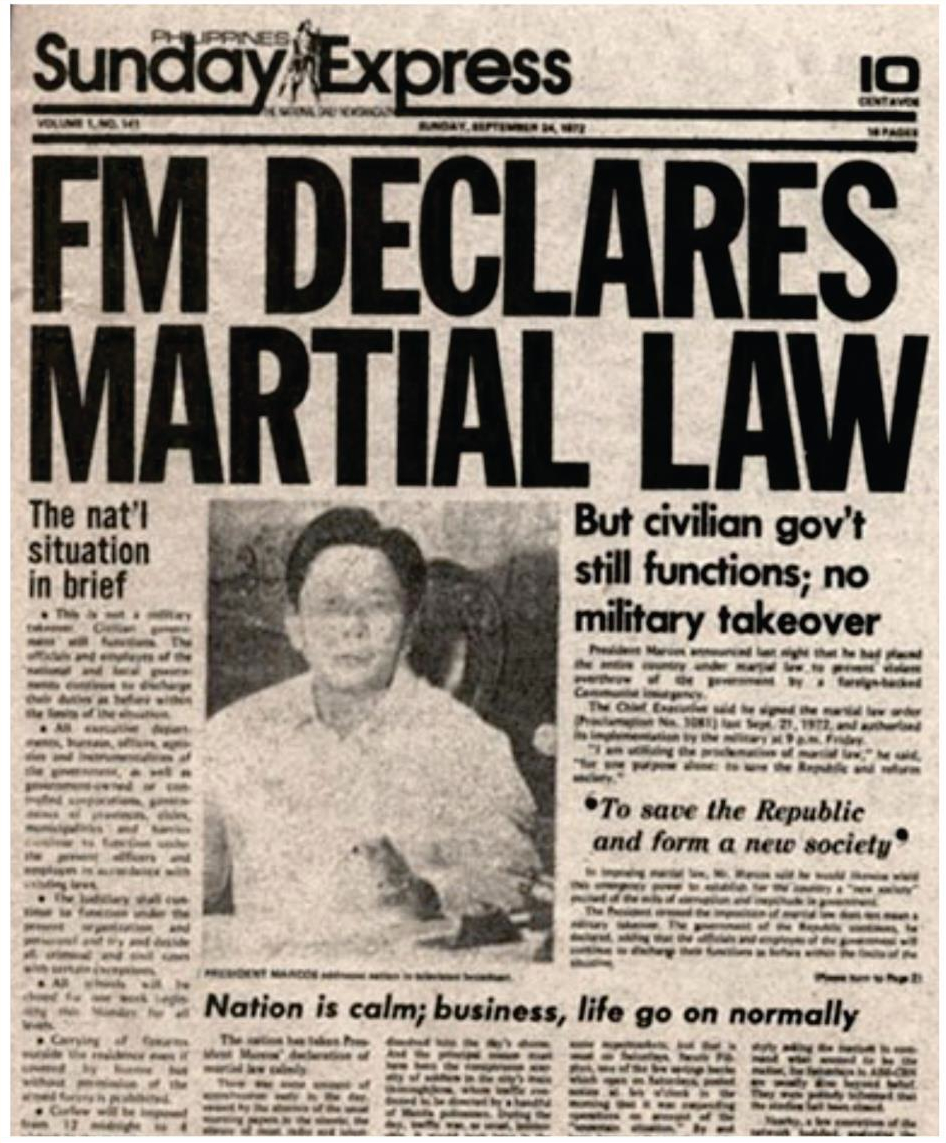

Ferdinand Marcos had been president of the Philippines since 1965. After declaring martial law in 1972, he suspended and eventually rewrote the Philippine constitution, curtailed civil liberties, and concentrated power in the executive branch and among his closest allies. Marcos had tens of thousands of opponents arrested and thousands tortured, killed, or disappeared.

The Sunday Express headline from September 24, 1972 shortly after Marcos declared martial law.

For two decades, Filipinos lived under authoritarian rule while Marcos and his allies enriched themselves through ownership of Philippine press and industry outlets and through the siphoning of funds from U.S., World Bank, and International Monetary Fund loans.

The People Power movement had been building since well before Marcos’s declaration of martial law. Committed activists who organized underground in the Philippines, in exile, and in the diaspora worked tirelessly to broadcast news of the Marcoses’ human rights violations and ill-gotten wealth globally.

For many years, however, much of the world—the U.S. government in particular—was perfectly willing to overlook the corruption of the Marcoses in exchange for an anti-Communist bulwark in Southeast Asia.

By the mid-1980s, however, foreign policy calculations had shifted against Marcos in crucial ways.

Senator Benigno Aquino in an interview with Pat Robertson before his assassination in 1983.

The August 1983 assassination of Senator Benigno Aquino, Jr. was seen by many around the world as a particularly brazen act of political retribution. Furthermore, rumors about Marcos’s health (he was suffering from lupus and regularly undergoing dialysis at the time) led many of his allies in the Philippines and beyond to begin speculating about the dictator’s successors.

When Ferdinand Marcos boldly called for a “snap election” in a 1985 interview with David Brinkley, Marcos’s opponents weighed whether this was an opportunity or a trap. Many times before, Marcos had tipped the electoral balances in his favor, through a rewriting of laws, outright violence, and other forms of manipulation and intimidation.

Much of the Philippine Left decided to boycott the election, fearful that participation would only serve to further legitimize the regime. The remainder of the opposition movement eventually coalesced around the widow of Senator Aquino, Corazon “Cory” Aquino.

Just as many feared, Marcos claimed victory in the election. This time, though, Filipinos refused to accept this lie. On February 22, citizens took to the streets on Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (EDSA). Cardinal Jaime Sin, the Archbishop of Manila, called upon Filipinos to support the peaceful protests.

Cardinal Jaime Sin pictured in 1988.

Marcos ordered the military to repress the mass action. However, a faction of military officers refused to clamp down on the protestors and chose instead to defect. This group included soldiers who had grown frustrated with corruption in the military and the Marcos regime and had earlier formed the Reform the Armed Forces Movement (RAM).

When Marcos ordered the military to arrest detractors, Cardinal Sin called upon the people to shield them. The Catholic radio organ, Radio Veritas, became a major control center for protest communications during the People Power movement.

Close Marcos ally President Ronald Reagan eventually sent word through Senator Paul Laxalt that it was time to “cut, and cut cleanly,” signaling that Marcos no longer had the backing of his most powerful ally. On the evening of February 25, the U.S. government facilitated Marcos’s escape to Hawaii, where he would remain until his death in 1989.

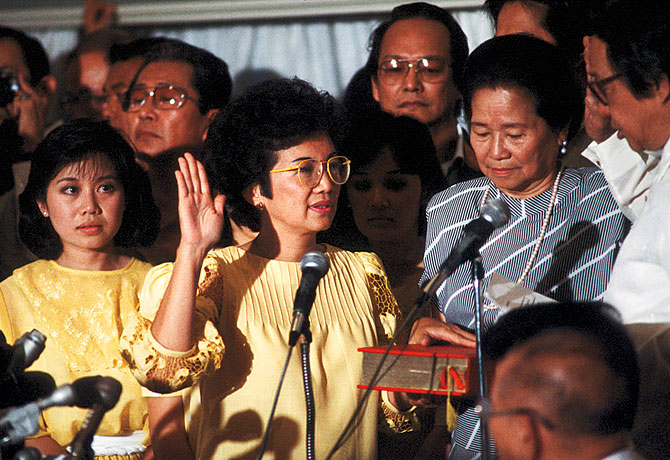

Later that same night, protestors stormed Malacañang Palace, exposing the opulent wealth that the Marcos family had amassed during their time in power. As Corazon Aquino was sworn in as President, Filipinos were hailed around the world as an example of peaceful revolution and the restoration of democracy.

The road ahead would not be so simple, however. In the years since 1986, the legacy of the People Power Revolution has remained uncertain. Aquino faced several coup attempts during her time in power, many of them led by the very same RAM that had helped facilitate her rise to power.

The agricultural and economic reform that many Filipinos hoped for in a post-Marcos world did not come. Peace talks with the Communist Party of the Philippines dissolved and leftists continued to be maligned, attacked, and hunted.

Many Filipinos expressed nostalgia for the very dictator that had been overthrown. And there have been ongoing projects of historical revisionism in the Philippines that sanitized the Marcos years.

The Marcos family have returned to the Philippines and to positions of political prominence: Ferdinand Marcos’s widow Imelda became a congresswoman and his daughter Imee a governor. Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., the dictator’s son and evident successor to his father’s legacy, ran for vice president in 2016 and finished a close second. Bongbong refused to concede and, to this day, continues his legal challenges to the election.

President Rodrigo Duterte talks to Imee Marcos at a wedding ceremony in Manila, September, 2016.

The most concerning outcome of the 2016 Philippine elections, however, was the election of Rodrigo Duterte as president. A close ally of the Marcoses, Duterte has drawn upon Marcos’s script for authoritarian power. He has arrested prominent opponents, curtailed civil liberties, and claimed that discipline is what is most needed for the Philippine nation.

Most infamously, Duterte launched a campaign that has resulted in tens of thousands of extrajudicial murders committed by police and military forces.

The People Power Movement offers several lessons. We can see the courageous solidarities and coalitions that might mobilize against authoritarian restrictions on civil liberties. But we must also look at the importance of finding ways to build anew and address the grievances and injustices that have made such authoritarians so popular in the first place.

The EDSA protests in 1986 were a remarkable moment in Philippine history, a moment filled with the sense of unlimited hope and possibility. And for those with democratic dreams, it provides both a lesson and a warning for the battles ahead.