The shooting started in the early morning, 4:45 AM, September 1, 1939, when the obsolete German battleship Schleswig-Holstein opened fire from its berth in the Free City of Danzig.

As the ship’s big guns hammered Polish fortifications on the Westerplatte peninsula, undercover agents of the Schutzstaffel, the SS, began seizing control of key buildings in the city. The workers in the post office held out until, outgunned, they retreated into the basement. Their attackers then lit the building on fire. The survivors staggered outside to surrender where the SS men gunned them down.

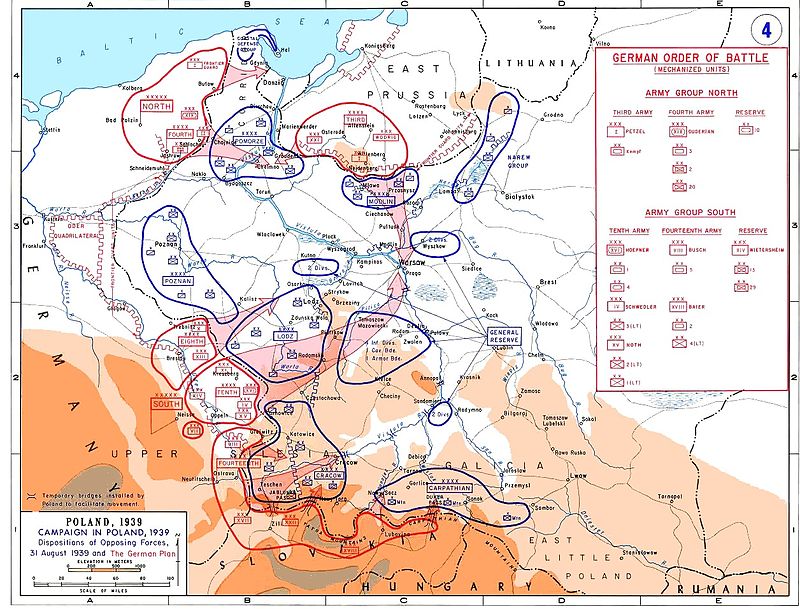

The assault on Danzig was the opening act of the full-scale invasion of Poland as some one-and-a-half million men of the German Army moved out of their encampments and into combat. It was the beginning of a war over the future of Poland; it was the beginning of the Second World War, a struggle for the fate of the world.

In 2014, when Russia forcibly annexed the Crimean peninsula from Ukraine, Poles were among those who protested most loudly. No surprise since the Russian act of aggression came just before the 75th anniversary of the German invasion of Poland. The memory of World War II remains potent across Europe, especially for Poles, and conditions the way many there respond to current events.

Modern Poland was born in the Treaty of Versailles that ended the First World War, an old/new nation that incorporated the predominately Polish-speaking lands that had been part of Germany, Austro-Hungary, and Russia.

Danzig, governed under the auspices of the League of Nations, sat on a strip of land, the Polish Corridor, carved between East Prussia and the rest of Germany to provide the new nation with access to the Baltic. The ethnically mixed corridor was a clear flashpoint for conflict, especially after the rise to power of Adolph Hitler and his National Socialist German Workers Party, the Nazis, in 1932.

British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain shaking hands with Hitler in September of 1938.

Until the fall of 1939, Hitler’s ambitions of uniting the German-speaking territories, in preparation for a drive to seize “living space” or Lebensraum in Eastern Europe, had proceeded successfully through the application of guile, bluff, and terror.

Britain and France, acting in the shadow of a generation lost to the trenches, had pursued a policy of “appeasement” that sought to satiate Hitler’s ambitions in order to avoid another war. This policy culminated in 1938 when Britain and France agreed at Munich to allow Germany to annex Czechoslovakian territories bordering Germany. When British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain returned to London he promised an anxious nation that he had achieved “peace for our time.”

Hitler had other plans.

In early 1939, Hitler annexed the Czechoslovakian provinces of Bohemia and Moravia and forced Lithuania to surrender the Baltic port city of Memel. Faced with the prospect of unrestrained German aggression, Britain and France offered security guarantees to Poland in March 1939.

Hitler believed, however, that the two nations were bluffing and would only offer token resistance to a German invasion of Poland, or none at all. That same month, he ordered preparations for an invasion of Poland.

Further enhancing the Fuehrer’s confidence was the successfully negotiation of a non-aggression agreement, the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, between Germany and its ideological arch-nemesis, the Soviet Union, on August 23, 1939. In a secret annex to the treaty, the two nations agreed to divide Poland.

The results of the German offensive, a “lightening war” or Blitzkrieg, were devastating.

A Polish lieutenant observed what remained of his unit after it had been first hit by bombing and then assaulted by tanks and artillery: “The extent of the death, destruction and disorganization this combined fire caused in three short hours was incredible. By the time our wits were sufficiently collected even to survey the situation, it was apparent that we were in no position to offer any serious resistance.”

Polish light tanks at the start of the 1939 Defensive War.

The Polish Army did resist nonetheless, bravely and sensibly. The enduring stories of the Polish cavalry charging German tanks en masse were fabrications crafted by Nazi propaganda. The overwhelmed Polish air force was not caught flatfooted on its airfields. But from September 1st onward, the Polish military was overextended, underequipped, and outmaneuvered—a losing proposition.

Blitzkrieg promised quick and decisive victories, avoiding the trench-to-trench slaughters at places like Verdun and the Somme that had defined the Western Front in World War I. But it opened the space of combat for other kinds of violence.

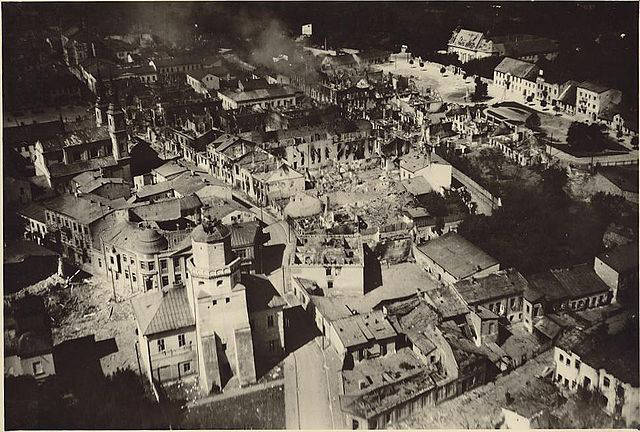

The killings at the Danzig post office were far from the day’s only atrocity. The Luftwaffe bombed not only the Polish rear-echelon but also cities and towns such as Wieluń, which was leveled on the first day of the war. The air offensive destroyed passenger trains, and machine-gunning columns of fleeing civilians. The German Army dealt ruthlessly, and illegally, with anyone or anything that hindered its advance: taking (and shooting) hostages, destroying villages, and summarily executing members of Polish militia units that resisted the invasion.

German cavalry and motorized units spread throughout Poland in 1939, by way of East Prussia.

Even more systematic plans for mass murder were already well afoot. Moving behind the advancing units of the German Army, with whom they would closely cooperate, were “Operational Groups” or Einsatzgruppen. These insipidly named teams of SS and police forces were tasked with murdering any Poles who could conceivably threaten Hitler’s plan for a Germanized Poland. In late August 1939 the list of planned victims already extended to 61,000 people: intellectuals, nationalists, the clergy, the nobility, teachers, and prominent Jews. By December 1939, German paramilitaries had killed an estimated 50,000 Poles.

As industrialized violence engulfed Poland, the last hopes for peace faded away. At 10 AM on September 1, Hitler, dressed in a field-grey jacket appropriate to the self-proclaimed “first solider of the Reich,” addressed German’s ersatz parliament. He gave a short speech, telling the assembled deputies and Nazi party officials “Danzig was and is a German City. The Corridor was and is German.” The appeal to ethnically based nationalism was echoed this year by Russian President Vladimir Putin to justify his actions in Ukraine.

Outside, a mood of dismay and resignation shrouded the streets of Berlin. The Belgian Ambassador, who had been in the capital for the outbreak of the First World War, wrote “In 1914 the war began with enthusiasm. Soldiers were mobbed and garlanded with flowers. They left for the front as though on holiday. . . . In 1939 everything is different . . . (Hitler’s) harangue is received with the obligatory applause of deputies paid for the purpose. There was none of the delirious acclaim. Few people were in the streets to observe the troops march past.”

The allied governments in London and Paris drafted and issued their final warnings to Hitler. At 6 PM Chamberlain told the House of Commons that war appeared inevitable. That evening in Berlin, the British Ambassador made it clear that ”unless the German Government are prepared to give His Majesty’s Government satisfactory assurances that the German government has suspended all aggressive action again Poland and are prepared promptly to withdraw their forces from Polish territory, His Majesty’s Government . . . will without hesitation fulfill their obligations to Poland.” That evening, Britain lay under the cover of blackout.

In the United States on September 1st, President Roosevelt, decrying the bombing of “unfortified centers of population” as “inhuman barbarism” warned that if such tactics became the norm “hundreds of thousands of innocent human being who have no responsibility for, and who are not even remotely participating in, the hostilities which have now broken out will lose their lives.” He asked the major powers to Europe to abstain from turning each other’s cities into charnel houses. No country, including America, kept that pledge in the war that followed.

Germany gave no assurances in reply to the Anglo-French demands and on September 3rd both Britain and France declared war.

This commitment drew in both nations’ colonial empires and turned a war over the fate of Poland into a Second World War. Neither of Poland’s allies, however, dared to make a significant thrust, by land or by air, to relieve the pressure on the Poles. That day, the Royal Air Force ineffectually bombed the German fleet and dropped millions of leaflets.

In the United States on September 3rd, President Roosevelt gave a “fireside chat” to the American people, telling them “This nation will remain a neutral nation, but I cannot ask that every American remain neutral in thought as well.” There would be no specious equivalence drawn by the United States government between German aggression and the British and French response.

Poland’s fate was sealed on September 17th when the Soviet army invaded from the east to seize the territories promised to the USSR in Molotov-Ribbentrop pact. Caught in the vise of two invading armies the last Polish units surrendered on October 6th.

The German invasion killed 70,000 Polish troops, wounded at least 133,000, and captured almost 700,000 men. Germany, with losses of 11,000 killed, 30,000 wounded and 3,400 missing, had not achieved a bloodless victory, but the disparity in causalities illustrates the unequal nature of the contest. Some 150,000 Polish soldiers and airmen managed to escape and continue the war in the armed forces of the Allies.

A Polish civilian injured by Luftwaffe, the aerial branch of the German military.

More than eighty years have passed since those fateful September days. Germany, Britain, France, and Poland are now bound together militarily, through the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, and politically, through the European Union.

World War II began on Polish soil and in the ensuing six years Poland became the site of a majority of German concentration camps. Though it no longer shares a border with Russia, as it did during the Soviet period, many Poles continue to see the world through the lens of 1939.

Indeed, the war that ended over two generations ago still seeps into the wars of our own time. In eastern Ukraine today fighting rages between pro-Russian separatists and the Kyiv government. Both camps have traded accusations of “genocide” and the labels of “anti-fascist,” “pro-fascist,” and “Nazi,” in describing each other’s objectives and conduct.

Similar rhetorical exchanges have marked the narratives that Israel, Hamas, and their respective supporters, have deployed against each other in the recent conflict in Gaza. “Appeasement” and “appeaser” remain terms of opprobrium in debates over foreign policy.

The unquiet ghosts of September remain. They frighten us still—as well they should.