Fifty years ago this September the first episode of Star Trek hit the American airwaves. Since that original series aired, Star Trek has spawned thirteen feature films, six subsequent series including one animated version (the sixth series will debut in 2017) hundreds of novels and comic books, and countless toys, games, uniforms and other merchandise.

Star Trek: The Original Series logo (left), and the show's 1968-1969 third season cast (right).

Star Trek and its fans have become one of the archetypes of both the undying multi-media franchise and of the devoted, even obsessive, fan base. Yet, even if the original series had not inspired such subsequent successes, its own historical significance would have been worth noting.

When Star Trek first appeared in 1966, the media landscape was quite different than it is today. While there were a handful of other science-fiction shows on the air, the three television networks remained dominated by variety shows, fluffy situation comedies, spy and police thrillers, and ubiquitous westerns. Moreover, while science-fiction had a rich literary tradition, it was all too often thought of by the general public as the realm of B-movie drive-in fare, like The Blob, or of pulpy juvenilia, such as Buck Rogers or Flash Gordon.

William Shatner as Captain Kirk and Leonard Nimoy as Mr. Spock pose behind a model of the starship Enterprise.

Star Trek, while having its own monsters and B-quality special effects, reintroduced to the American public science-fiction that grappled with important ideas and big issues. It filled a void left by the cancellation of The Twilight Zone two years prior. The central place of “big ideas” in the Star Trek franchise reached its apex in 1982’s movie Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. That movie can be described as a philosophical debate between Nietzschean ethical egoism and Jeremy Bentham’s ethical utilitarianism framed by quotations from Melville and Dickens.

Surprisingly, considering its later success, Star Trek suffered low ratings in its original run and was cancelled after three seasons and only 79 episodes. The show, however, survived as a cult favorite in syndicated re-runs, and was nurtured by a community of fan clubs, conventions, and magazines.

This was at a time when science fiction was considered the realm of outsider subcultures—“geeks” and “nerds”—before George Lucas and Steven Spielberg would make mainstream blockbuster science-fiction films, and before the current day when science-fiction, and the related genres of fantasy and superheroes dominate television and cinema screens. It wasn’t until 1979, in the wake of Star Wars’ success, that this fan enthusiasm would support a Star Trek feature film, and, in 1987, a new television series.

The Starship Enterprise from Star Trek: The Original Series (left), and "Trekkies" gathered at a convention in Las Vegas (right).

Star Trek was both a reflection of, and ahead of, its time. It was a product of the Cold War, the Civil-Rights and anti-war movements, and the counter-culture that was then roiling the United States. Star Trek addressed these issues obliquely by clothing the issues of the day in the costuming of the future.

Flag of the United Federation of Planets.

The Cold War between the United States, Russia and China was mirrored in the uneasy peace between the United Federation of Planets and their enemies, the Klingons and the Romulans. Episodes dealt with the absurdity of racism (“Let That Be Your Last Battlefield”,) the follies of Vietnam (“A Private Little War,” “A Taste of Armageddon,”) and the dangers of the Cold War (“The Omega Glory.”) Some of these parallels to the culture of the sixties seem risible in hindsight, such as when Captain Kirk encounters what can only be called space hippies, (“The Way to Eden,”), yet the show’s concern with these issues was sincere.

Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry’s interest in race and gender equality was reflected not only in the storylines of the series, but in its production and casting as well. Arguably the most important aspect of the original show was the casting of Nichelle Nichols as Lt. Uhura, the Enterprise’s communications officer. Having an African American woman in a position of competence and authority was a rarity on American television in 1966 and an inspiration to young black women watching. Both actress Whoopi Goldberg and astronaut Dr. Mae Jemison have cited Uhura as inspiring them to follow their respective careers.

Nichols was thinking of leaving Star Trek when Martin Luther King Jr. visited the set. He insisted that she remain on the show because her example was too important. Further, when Uhuru and Kirk kiss in one episode, “Plato’s Stepchildren” theirs was arguably the first interracial kiss ever seen on American television.

Gene Roddenberry, the creator of Star Trek, addresses a group of fans (left), and Nichelle Nichols as Communications Officer Lieutenant Uhura (right).

However, there were limitations imposed on the show. In Roddenberry’s original pilot episode, the first officer was a woman, and wore pants. The network, NBC, axed the female first officer and dressed the female crew in miniskirts. Moreover, many of the female characters on the original series were simply disposable love interests for the male characters. The role of women in subsequent series would improve over time. By 1995, Star Trek: Voyager featured a female captain.

William Shatner as Captain Kirk, in the 1967 episode "The Trouble with Tribbles."

This commitment to equality was a reflection of the larger vision of the show. For while the world of the 23rd century is at times brutal and violent, Roddenberry’s vision of the future is still a utopian one. The Earth has achieved peace—Russians and Americans, former enemies, now work together. Poverty and racism have been eradicated, and technology allows humanity to carry these benefits to the stars, though respecting “The Prime Directive,” the Federation’s principle of non-interference with less developed civilizations.

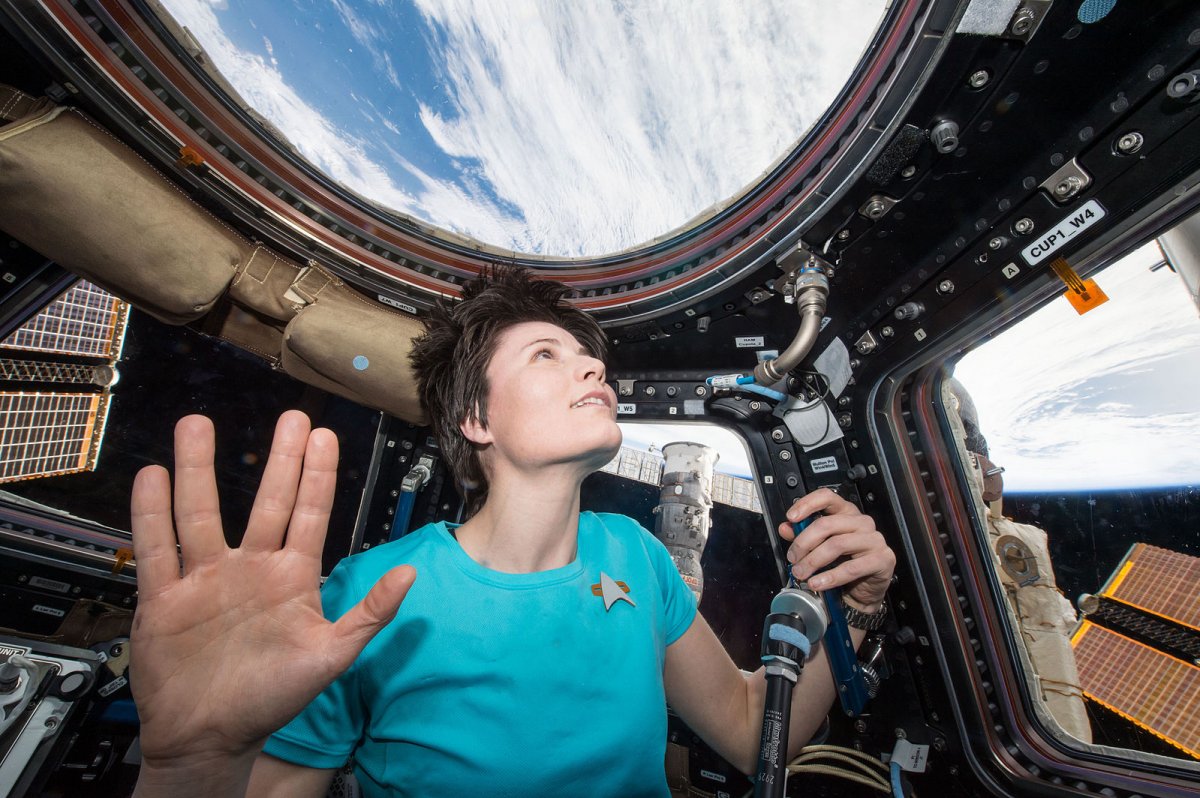

Star Trek was born of both the tumult and the optimism of the 1960s, with the belief that by confronting the darker elements of our nature, humanity can overcome them and build a greater future. It is this optimistic vision that accounts for much of the success and longevity of the series: the hope that together we may all “Live Long and Prosper.”

Astronaut Samantha Cristoforetti giving the "Vulcan Salute" in tribute after the recent death of Star Trek actor Leonard Nimoy in February, 2015.