On December 6, 1922, Ireland’s struggle for independence from the United Kingdom reached a turning point. With the creation of the Irish Free State, 26 of 32 Irish counties received considerable, albeit not complete, independence.

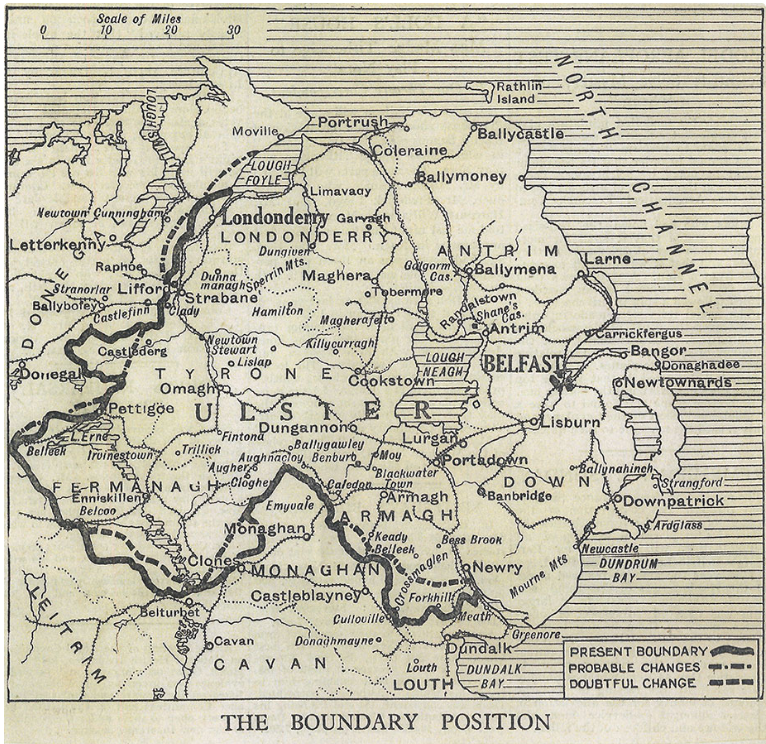

The following day, however, six counties in the historical province of Ulster, located in the north of the island, opted out of the Free State, remaining instead in the United Kingdom as the province of Northern Ireland.

The road to Irish independence led to Irish division.

Although England held a presence in Ireland since the late 1100s, this political division was the consequence of a cultural differentiation that began much later. In the 1590s, the Ulster nobleman Hugh O’Neill led a decade-long rebellion against England, which had only just been suppressed when King James I ascended the throne in 1603.

James then encouraged the large-scale emigration of Protestants from England and Scotland to Ulster. By populating the rebellious north of Ireland with loyal Protestants, James hoped to transform and subdue Ireland.

James was only partially successful. Given legal privilege and title to land, Protestants flourished in the north of Ireland and became a bulwark of support for the English crown in the following centuries. The Catholic majority of Ireland, in contrast, came to resent the situation and their relationship with the Protestant minority became one of tense, often confrontational, coexistence.

By the 1800s, these regional differences fostered two distinct senses of national identity. In the north, Ulster Protestants tended to identify with the United Kingdom and staked their political future on the preservation of the Union. In political terms, they came to describe themselves as Unionists.

In much of the rest of Ireland, Roman Catholicism, a desire to break the union with the British monarchy in favor of an Irish Republic, and the revival of the Irish language and traditional culture characterized nationalist identity. This sense of political identity was understood simply as Irish nationalism or Republicanism, by those vowing to break ties to the British crown by any means necessary.

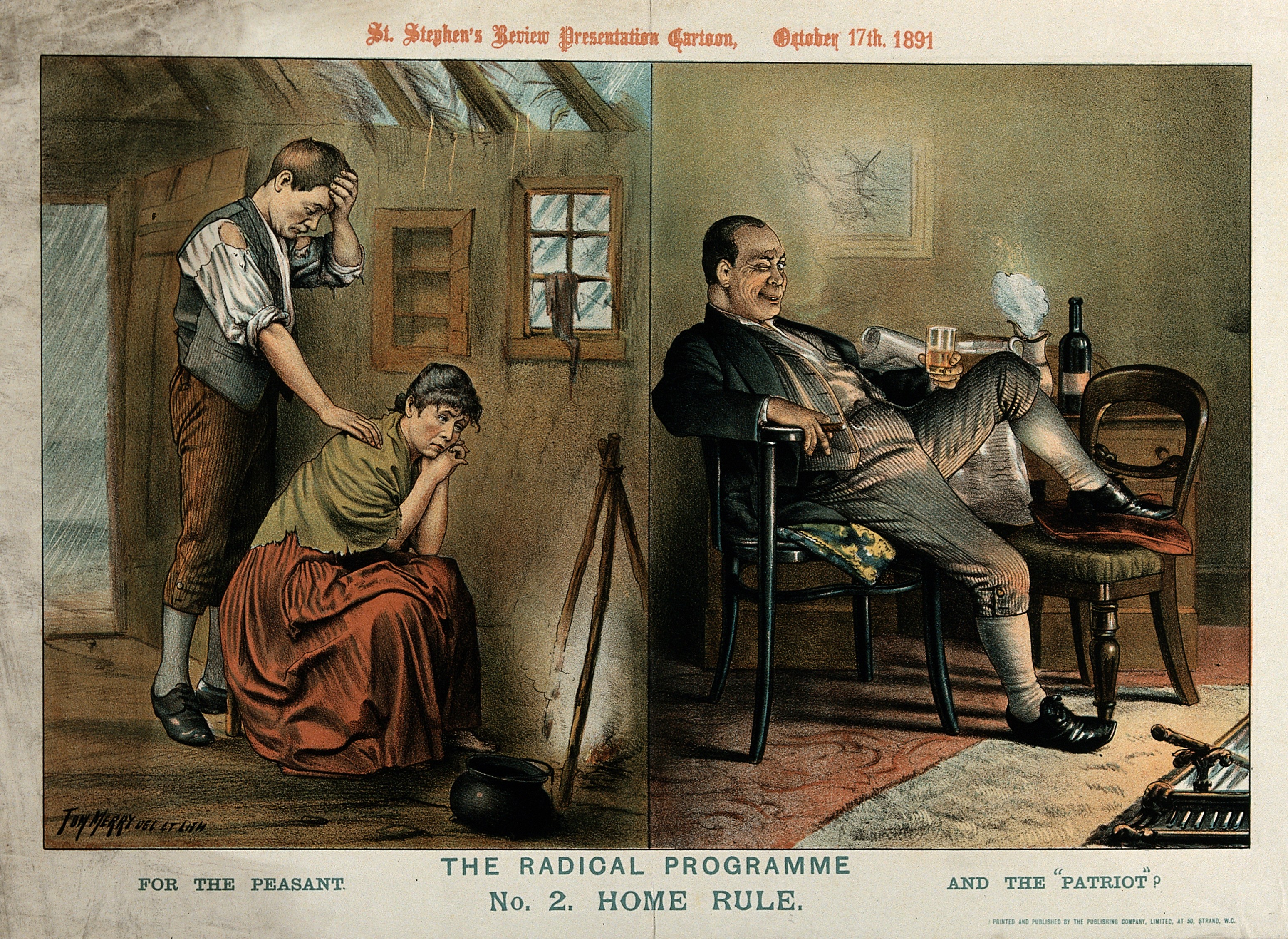

It was not inevitable that these national identities would lead to partition. In the late 1800s, the British Labour Party introduced the possibility of Home Rule as a way of compromising on the so-called Irish question. Home Rule would open an Irish parliament in Dublin and devolve considerable authority to it while keeping Ireland within the United Kingdom.

The first two efforts to pass a Home Rule bill, however, failed in the British Parliament. By the turn of the century, proponents of Unionism and of Irish nationalism were coming to see their two traditions as mutually exclusive to one another.

Parliament narrowly passed a Home Rule bill on the eve of the First World War. By this time, political sentiment in Ireland became increasingly polarized, meaning that the autonomy promised by Home Rule would be too much for Unionists, fearing minority status in a Home Rule Ireland, and not enough for nationalists desiring full independence.

Unionists, therefore, vowed to resist Home Rule by force and, under the leadership of Dublin Lawyer Edward Carson, formed the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), an anti-Home Rule militia. English politicians were split on the issue, with conservatives worried that enacting Home Rule might encourage nationalist movements elsewhere in the Empire.

Officers in the British Army also worried about maintaining the Empire and were sympathetic to the position of Ulster Protestants. They made it clear that they would not enforce Home Rule in the north if the people opposed it.

In 1916, Irish nationalists staged a symbolic rebellion on Easter Monday in Dublin and proclaimed a provisional Irish Republic. The British were able to suppress the rebellion, but in the years that followed, the explicitly separatist Irish national sentiment it represented spread among the people of Ireland. When the first parliamentary elections after the end of the war were held in late 1918, the hardline nationalist party Sinn Fein won a decisive victory.

Events moved quickly following the 1918 election. In early 1919, Sinn Fein delegates refused to take their seats in Parliament, declaring instead an Irish Parliament (Dail Eireann) in Dublin and launching a formal war for Irish independence.

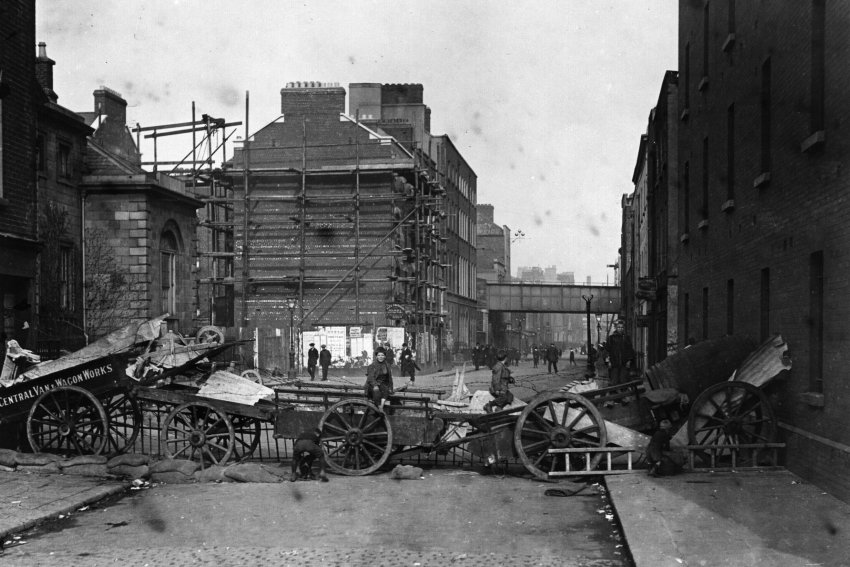

At first, the British chose not to use the full might of their military against Ireland, so the resulting war was more a small-scale insurgency comprised of surprise raids and attacks by Irish Republican Army forces and arrests and reprisals by the security forces.

To address the political crisis, the British Parliament passed the Government of Ireland Act in November 1920. The act intended to reconcile the Unionist desire to remain within the United Kingdom with the nationalist desire for greater independence by partitioning Ireland into two Home Rule governments. Six counties in Ulster—Fermanagh, Antrim, Tyrone, Londonderry, Armagh, and Down—received considerable autonomy and a local parliament, known as Stormont, that would eventually be built east of Belfast.

Two of these counties, Tyrone and Fermanagh, had Catholic majorities and had voted nationalist in the 1918 elections. Overall, the population of Northern Ireland was approximately 1/3 nationalist vs. 2/3 unionist. These demographics ensured that a somewhat scaled-down version of the conflict between the English and Irish would continue to plague Northern Ireland until the end of the 20th century.

While the Government of Ireland Act satisfied Unionists, it was completely inconsistent with the nationalist demand for Irish independence.

In the north, 1921 brought a degree of autonomy and state-building. On May 3, the act officially went into force, providing the legal framework for the creation of Northern Ireland. The parliament sat for the first time on June 7, and on June 22, King George V gave it his royal seal of approval.

Still, violence continued in both the north and the south. In Belfast, sectarian violence killed approximately 450 people between 1920-1922, the majority Catholic. Tens of thousands of Catholics had to flee their homes, many seeking refuge in the south.

The war between England and Ireland continued until the two sides agreed to a ceasefire in the summer of 1921. This was followed by the negotiation of a formal peace treaty in December, which gave the remaining 26 counties of Ireland considerable autonomy within the British Commonwealth.

In January, the Dail approved the Treaty by a 64-57 majority and created a Provisional Government for the Irish Free State. In June, elections were held for a new Dail, which was tasked with writing a constitution for the Free State, which in turn came into being on December 6, 1922.

Meanwhile, opponents of the treaty left the government and formed an armed opposition, igniting a bitter Irish-Irish war that would not be resolved until 1923.

It was a foregone conclusion, then, that Northern Ireland would formally opt out of the Irish Free State at the earliest possible occasion. It remained an integral part of the United Kingdom even as the Irish Free State severed ties and eventually declared complete independence as the Republic of Ireland.

![]()

Further Reading:

https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-northern-ireland-55401938

Ronan Fanning, Eamon de Valera: A Will to Power (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2016)

Diarmid Ferriter, The Border: The Legacy of a Century of Anglo-Irish Politics (London: Profile Books, 2019)

John Gibney, A Short History of Ireland 1500-2000 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017)

Peter Hart, Mick: The Real Michael Collins (New York: Viking: 2006)

Alvin Jackson, Home Rule: An Irish History 1800-2000 (Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press, 2003)

Alan F. Parkinson, A Difficult Birth: The Early Years of Northern Ireland, 1920-1925 (Dublin: Eastwood, 2020)