The Boxers, or Yihequan (“Righteous and Harmonious Fists” in Chinese), arose in Qing China at the turn of the 20th century as a reaction against foreign influence and a rejection of Western imperialism.

The Qing Dynasty, once the greatest power in Asia, had been sharply declining in the second half of the 19th century. Imperial incursions by Europeans, such as the Opium Wars with the British (1839-1841), and domestic unrest, like the Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864), substantially weakened the Qing state by stunting its economic growth and eroding its legitimacy.

Extraterritoriality, where foreign powers had de facto sovereignty over Chinese territory, was one of the most degrading aspects of Western imperialism in China. Foreign powers carved out areas, such as the German concession in Beijing, where residents were subject to foreign rather than Qing law.

These extraterritorial zones served as bases for Christian missionaries, who were making progress in converting some local Chinese. Many Chinese resented these Christian converts, seeing them as a direct representation of Western imperialism.

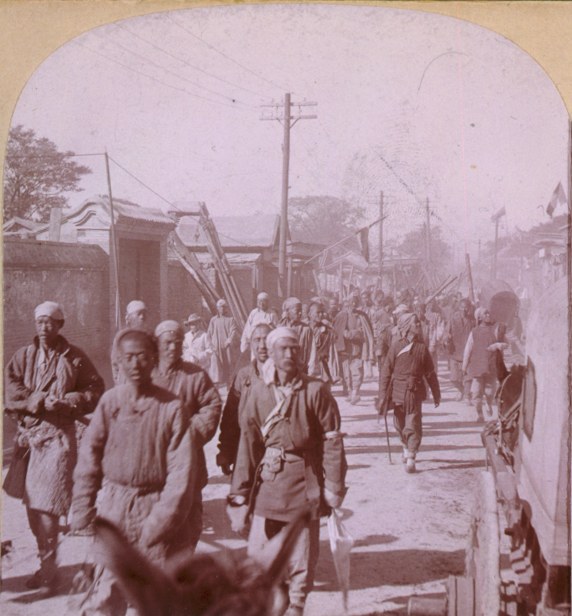

The flooding of the Yellow River in 1898 brought devastation to the countryside of northern China. Amid this misery, a mysterious group that combined traditional Chinese folk culture, including martial arts that they claimed made them impervious to bullets, and violent rhetoric and action against the hated Christian missionaries, began to gather momentum.

They dubbed themselves the “Society of Righteous and Harmonious Fists,” though Westerners simply dubbed them “Boxers.”

Cao Futian loosely led this decentralized group. In 1899, in Shandong and Hebei in Northern China, the Boxers began conducting sporadic violent attacks on churches, missionaries, and especially Chinese converts, massacring thousands in the process.

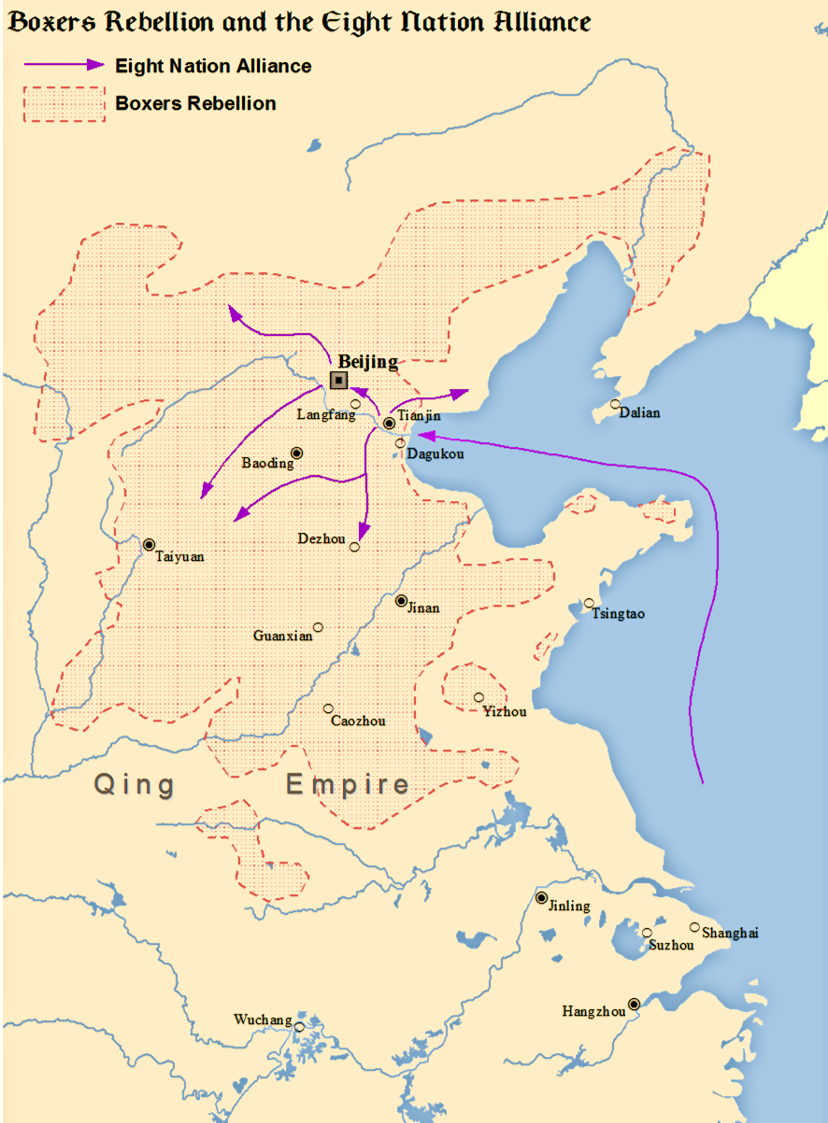

Western troops already in China quickly began to plan a counterattack on the Boxers. By June 1900, however, the Boxers halted the Western advance against them in Beijing and Tianjin.

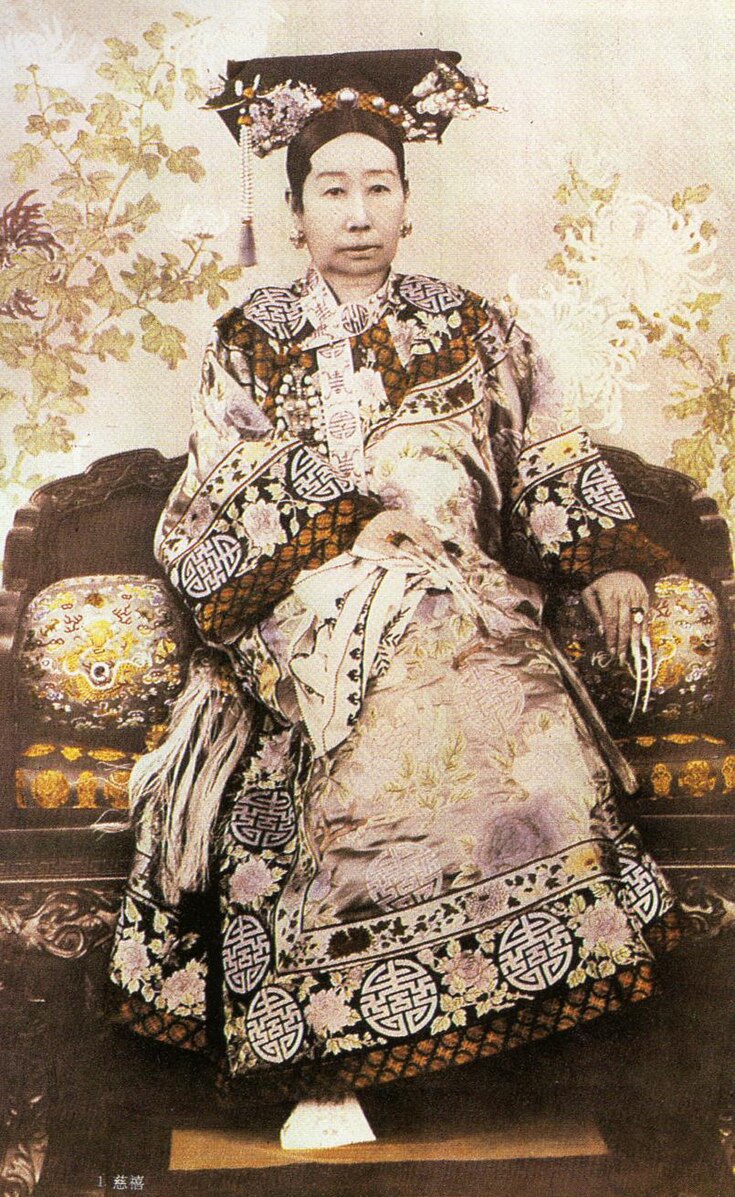

Initially, Qing forces suppressed the Boxers but there was a faction in the Qing court that favored collaborating with the Boxers.

By June 1900, Dowager Empress Cixi realized that the Boxers were tapping into a real resentment of the Chinese people by violently resisting Western influence in the country. In defiance of the imperial powers, Cixi formally switched sides to align militarily and politically with the Boxers on June 21, with an official declaration of war on all foreign powers in China.

The now-united Qing and Boxer forces put the foreign legations in Beijing under siege, threatening not just military forces and diplomats, but also Western women and children. In response to this affront, the major powers with concessions in China coordinated a relief effort under the banner of the “Eight-Nation Alliance.” These nations were France, Austria-Hungary, Italy, Germany, Britain, Russia, the United States, and Japan.

This force numbered 55,000 troops at its peak, half of them Japanese. They first took back the port city of Tianjin on July 14 and used this as a base to launch an incursion into Beijing. There was a month of brutal fighting, with roughly 3,000 military casualties altogether, mostly among Qing and Boxer troops. The allies stormed Beijing on August 14, relieving the besieged and bedraggled foreign delegations that had held out for six weeks.

When it became clear that the Eight-nations would take the capital, Cixi and the imperial court fled Beijing for Xi’an. Western troops proceeded to commit atrocities of their own, looting much of the city and massacring anyone with suspected connections to the Boxers, with estimates putting the civilian death count as high as 100,000 for the whole conflict.

The Eight-Nation Alliance occupied Beijing, Tianjin, and Zhili for a year as they conducted negotiations with the Qing to end the war. These negotiations culminated in the Boxer Protocols of 1901, where China was made to pay a crippling indemnity of 450 million taels of silver to the Eight-nations, allow foreign troops to reside in Beijing, and punish] any of their officials who supported the Boxers, many by execution.

These protocols represented a particularly painful episode in what contemporary Chinese nationalists referred to as the broader “century of humiliation” (1839-1949), where a once powerful China was unable to fully resist Western and Japanese incursions.

It was also a near-death knell for the Qing dynasty, which staggered on for another decade before being overthrown by the Nationalists (Guomindang) in the 1911 Xinhai Revolution.

In his famous speech declaring victory in the Chinese Civil War (1927-1949) and announcing the creation of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, Mao Zedong proclaimed: “The Chinese people have stood up!” Though he did not refer to it specifically, Mao was indirectly invoking the Boxer Protocols as the imperial subjugation China was now “standing up” from.

Much of Chinese foreign policy today is motivated by preventing the recurrence of subjugation like this and in reaction to years of imperial reach into Chinese politics, economics, and society.

Chinese policymakers, from Mao to Xi Jinping in the present day, constantly clamor to never forget the horrors that outside powers inflicted upon China when they were weak. This serves as a powerful rallying call as China seeks to reclaim its historical identity as the “central kingdom” and project influence across Asia and the world.

![]()

Learn more:

Preston, Diana. The Boxer Rebellion: The Dramatic Story of China’s War on Foreigners that Shook the World in the Summer of 1900. New York: Walker & Company, 2000.

Silbey, David J. The Boxer Rebellion and the Great Game in China: A History. New York: Hill and Wang, 2013.

Chen, Jian. Mao’s China and the Cold War. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

Wang, Zheng. Never Forget National Humiliation: Historical Memory in Chinese Politics and Foreign Relations. Columbia University Press, 2012.