A few years ago Thomas Jefferson received a demotion from the Texas State Board of Education. The conservative Republicans on that august body voted to remove Jefferson from the first rank of Founding Fathers in the state’s high school curriculum. The reason for this posthumous pink-slip was not that Jefferson was a slave-holder or even that he fathered children with one of those slaves. Rather, Jefferson’s sin in the eyes of those Texans was to have authored the phrase “a wall of separation between church and state.”

Jefferson, along with James Madison, Benjamin Franklin, and others, did indeed contribute to making the United States a secular nation, and in Andrew Copson’s short book Secularism he occupies a more honored place than he does now in Texas.

This book is more philosophical essay than historical evaluation. Copson has presented a brief in favor of secular government grounded in historical examples. Copson is not making a case for or against religion as such – Richard Dawkins and the late Christopher Hitchens have both offered robust arguments for atheism. What interests Copson is to find the most fruitful relationship between religious belief, practice, and institutions and civil government and the public sphere. Secularism, he argues, is our best way to achieve civic harmony while protecting the right to religious freedom.

While the concept itself has deep historical roots, the term secularism itself dates only to the 19th century, when it was coined by British reformer George Jacob Holyoake. In this book, Copson relies on the concise definition offered by French scholar Jean Bauberot. Bauberot sees three essential components to a secular society: 1) the separation of religious institutions from the institutions of the state; 2) freedom of conscience for all individuals, circumscribed only by the need for public order and the respect of the rights of other individuals; 3) no discrimination by the state against individuals on the basis of their beliefs.

With that as a guiding framework, Copson examines the way secularism emerged in the West, especially as a consequence of the Reformation. Overthrowing the political hegemony of the Catholic Church opened the possibility that state and church could operate in separate realms.

This is a prelude that gets us to Copson’s main interests. After this quick background, Copson brings us to revolutionary America and revolutionary France, the first two nations to establish themselves on explicitly secularist terms. Among the few illustrations in this book is a full-page photo of Thomas Jefferson’s gravestone – Jefferson famously instructed that only three things be inscribed on the stone, one of which was his authorship of the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom.

The two revolutions, needless to say, had different trajectories – in part because the French Revolution was much more explicitly anti-clerical than the American one (Americans were no less hostile to Catholic priests than the French, there were just far fewer of them in 18th century America) – but Copson points out that through the tumult of French politics in the 19th century, the French commitment to what they call laïcité remained. By the Third Republic (1870-1940) it had become “a defining ideology of the state.”

It has become fashionable, especially in certain academic circles, to argue that secularism as a “defining ideology” is simply another Western imposition on societies that would prefer much more religion in their states. Tackling this, Copson pivots from France and the United States to Turkey and India. Both of those states, Copson reminds us, were founded explicitly as secular states. Turkey’s first constitution declared Islam as the state religion; that declaration was repealed in 1928 and by 1937 the Turkish constitution stated that the republic was laik – secular.

As he led the movement for Indian independence, Gandhi wrote in 1927 that he dreamt of an India “wholly tolerant, with its religions working side by side with one another.” The Indian constitution of 1949, adopted after Gandhi has been assassinated by a Hindu nationalist, enshrined the elements of secularism in law. Those elements were made even more explicit in the constitutional amendment adopted in 1976.

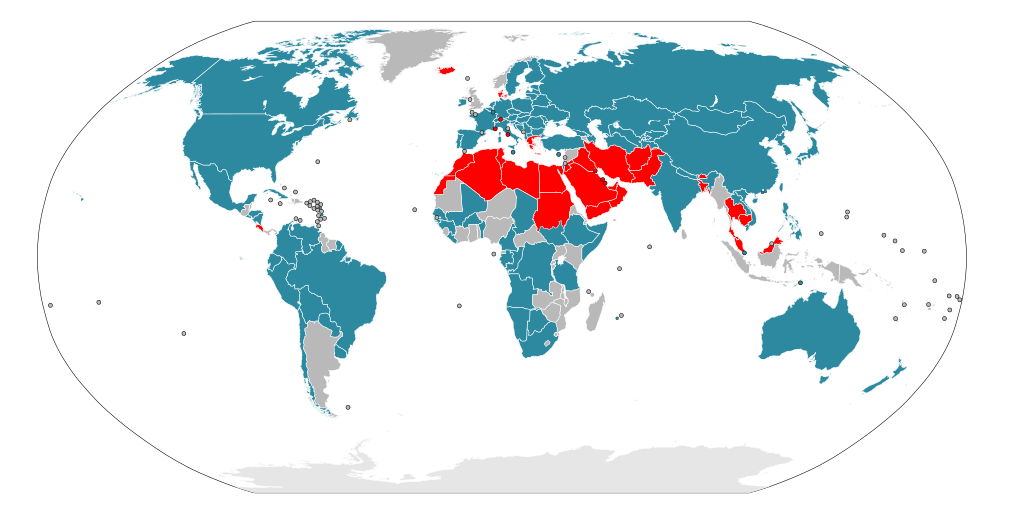

Copson does not present new history in these considerations, but he usefully underscores that secularism, while it may have originated in the West, has a strong global appeal. More to the point, in a society as dizzyingly diverse as India, secularism has real utility as a way to keep governments from promoting or discriminating against any particular faith. When the University of Texas surveyed 195 national constitutions from around the world, researchers found that over 70 of them declare some variation of the secularist ideal.

After these historical portraits, Copson devotes the remainder of the book to considering the different conceptions of secularism, examining their merits and the critiques that have been made of them. He has a rooting interest in these debates to be sure; he serves as the Chief Executive of Humanists U.K., an interest group that advocates for secularism among other things. Still, these chapters are fair and measured. Copson makes a persuasive case that if we want to balance the politics, religion, and freedom of his book’s subtitle, secularism, whatever its flaws, is our best hope.

There is a timeliness to this book that Copson touches on in his final chapter. Secularism is under attack around the world in ways that are as unexpected as they are frightening. 70 out of 195 national constitutions might be seen as a glass half full, or it might be seen as sluggishly disappointing. Whipping up religious hatred, whether for nakedly political purposes or for genuinely religious goals or both, has become depressingly common. Turkey and India under their current leadership are sliding further and further away from secularism and closer and closer to religious intolerance.

Though Copson doesn’t mention this, secularism emerged in the 18th century in part because of the memory of the Age of Religious Wars, and the Thirty Year’s War in particular. John Locke and James Madison and Thomas Jefferson and others understood full well that one predictable consequence of state-sponsored religion was that states would go to war over religion. “Men never do evil so completely and cheerfully as when they do it from religious conviction,” wrote Blaise Pascal. That remains as true today as when Pascal wrote it in the 17th century.