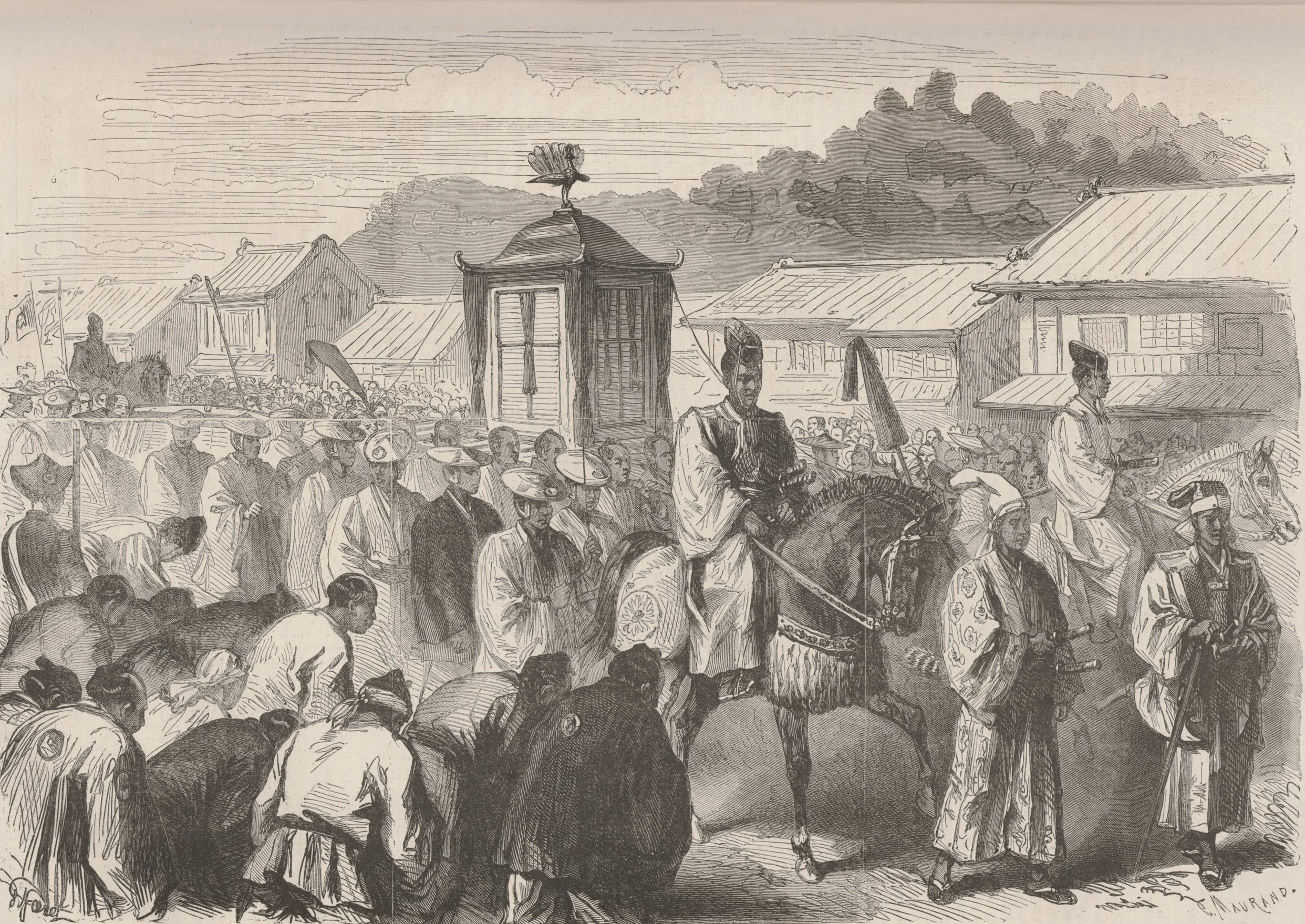

Japan’s Meiji Restoration, or Meiji Ishin, occurred on January 3, 1868, and marked the return of the Japanese emperor to a position of power for the first time in more than 500 years.

The Restoration happened when a coalition of powerful pro-reform forces led a palace coup d’état that ousted the Tokugawa military government that had ruled Japan since 1600. The collapse of the Tokugawa and handover to the new Meiji regime was swift and largely peaceful, resulting in the Restoration’s misleading “bloodless revolution” moniker.

Yet, if the Restoration was rather unremarkable, the transformations in Japanese politics, society, and economy seen over the next two decades were nothing short of revolutionary. Within five short years, the Meiji government dismantled the Tokugawa political structure of feudal domains and re-centralized local administration under governors appointed by the central government.

Pledging to unite all classes, high and low, government reformers abolished the samurai class, introduced a new conscript army, launched new industries, and established a national education system, all under the slogan “rich country, strong army.”

Global knowledge also became a cornerstone of the Restoration. Half of the Meiji ruling elite traveled to the United States and Western Europe for over a year on study tours to observe conditions outside Japan. They investigated new technologies and sociopolitical systems that could be used to accelerate Japan’s “progress” in the spirit of “learning from the West to catch up to the West.”

Promising to break off “evil customs of the past” in favor of the “just laws of nature,” progressive officials enacted far-reaching reforms. By 1889, Japan adopted the Gregorian calendar, Greenwich Mean Time, and a constitutional monarchy modeled on Prussia. It held national elections, seated a national parliament, and transformed Japanese social and sumptuary customs in the name of “civilization and enlightenment.”

Indeed, the historical significance of 1868 as a date lies less in the event of the Restoration itself but in the “spirit of 1868” that sparked the tremendous changes seen in Japan over the rest of what is now referred to as the Meiji period (1868-1912).

Events to mark the 150th anniversary of the Restoration took place around the world.

In Japan, thousands of local events, special exhibits, lectures, symposia, and ceremonies were held all over the country, in addition to the official Meiji 150th project sponsored by the office of former Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzō.

In sponsoring the Meiji 150th project, the Abe administration sought to reframe the Restoration as a politically convenient success story of rapid industrialization, collective nation-building, and national unification in the face of foreign threats.

“The ‘Meiji 150th’ project has two main goals,” explained cabinet secretary Uekusa Yasuhiko, “The first is to have the next generation of young Japanese learn about the spirit of Meiji, to prompt them to think about the future of Japan.”

He continued by linking back to the Restoration: “Japan’s current situation—a high rate of aging, low birth rate, and unsettled international relationships—is very similar to the beginning of the Meiji Period, when the way forward was unclear … It would therefore be beneficial to have the younger generation rediscover the Meiji spirit, to find the grit to face new challenges head-on.”

To achieve this goal, the official government narrative of the Meiji Restoration focused solely on the positive aspects of rapid growth and progress that allowed Japan to quickly transition from a feudal country to a “more free and democratic system that allowed the Japanese people to unleash their full potential.”

Abe himself directly invoked the Restoration to rally political support in a 2018 New Year’s statement: “We can change the future with our own hands,” he said. “It all depends on whether or not we believe that we can change the future and are able to take action, as our ancestors did 150 years ago.”

For Kataoka Shinichi, president of the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), the Meiji Restoration was a model that could be resold to other countries around the world to advance Japanese Official Development Assistance.

“As the first non-Western nation to become a developed country, Japan built itself into a country that is free, peaceful, prosperous and democratic while preserving tradition,” Kataoka described. “It is our hope that Japan will serve as one of the best examples for developing countries to follow in their own development…I firmly believe that there are quite a few aspects of Japan’s experience that can provide lessons for developing countries today.”

Not surprisingly, narratives of the Restoration as a success story leave out inconvenient historical truths.

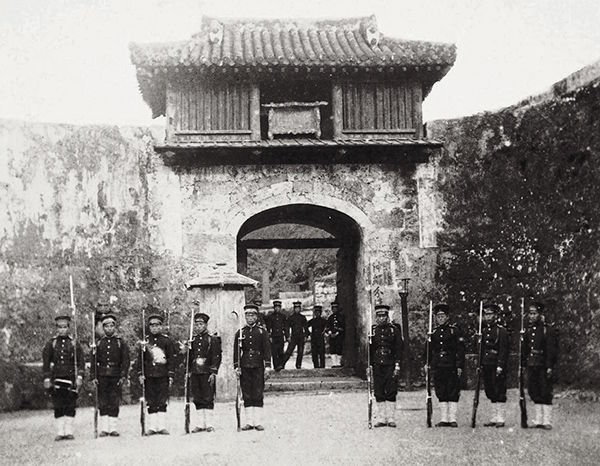

The list of “dark Meiji” history is long: the settler colonization of the northern island of Ainu Moshir (now Hokkaidō) and cultural genocide of the indigenous Ainu people starting in 1869; a long history of industrial disease and environmental destruction starting with the Ashio Copper Mine disaster in the 1880s; persistent poverty, famine, disease, and discrimination against former outcastes; the emergence of urban slums filled with marginalized populations; and the forced labor of POWs and colonized Koreans in the very same factories celebrated for launching Meiji industrialization and recently recognized by UNESCO as sites of World Heritage.

This is not to say that history should be easily bifurcated into simple binaries of success and failure, but instead to highlight the many topics that must be overlooked to sell the uncritical “Meiji as success story” narrative.

What, then, is the meaning of the Meiji Restoration for historians and scholars of Japan today? The Restoration certainly sparked revolutionary changes in Japanese society, politics, and culture that had a tremendous impact on East Asia and the world more broadly, for better and for worse.

Yet, studying commemorations like the Meiji sesquicentennial reveals how the legacy of historical events can be easily manipulated to suit differing political and diplomatic ends in the present, distorting the past in the process. As the past is re-presented in and for the present, historians must be there, if not to take a leading role, then to interrogate why, by whom, and for what ends.