Since their independence from the Soviet Union in 1991 the Central Asian countries of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan have seemed to Western observers like nations on the verge: not yet democracies but headed in that direction. This month historian Kyle Erickson explores this 30 year period to examine how their post-Soviet political systems were shaped and argues that they aren't likely to become genuine democracies any time soon.

Since their independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, many have characterized the Republics of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan as autocracies.

Not unusual for the Central Asian region, the two countries’ elections are widely seen as shams; their respective heads of state hold most of the political power, while citizens have few opportunities to meaningfully participate in political processes. Authority passes through a close-knit group of elites (both countries’ current presidents simply were the long-serving prime ministers of the former leaders).

The leaders are also openly kleptocratic. The individual presidents are widely assumed to hold immense personal wealth, and their family members often have lucrative government contracts and cushy sinecures in the public or private sectors.

Protests against the two governments face forceful repression.

The infamous Andijan Massacre in 2005 is estimated to have taken hundreds of lives after Uzbek security forces fired upon a crowd of demonstrators. In more recent memory, Kazakh and Russian forces killed at least 200 demonstrators in last year’s “Bloody January” in Kazakhstan, and they took nearly 10,000 into custody.

However, recent constitutional changes enacted in both countries appear to break from the autocratic past and complicate our understanding of their political future. In 2022, Kazakh voters approved changes to their nation’s constitution that were billed as “the final transition from a super-presidential form of government to a presidential republic with a strong Parliament.”

Uzbekistan followed suit in 2023 and unveiled a tranche of reforms ostensibly aimed at improving the nation’s record on human rights, enhancing the welfare state, and codifying environmental protection as a state priority. According to the Uzbek government, the “sole author” of these changes are the people of Uzbekistan.

Both reform packages passed through popular referenda with wide margins. The presidents of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan soaked up the glory, announcing the bright dawn of a new era. Posters and billboards in both countries applaud the “New Kazakhstan” and “New Uzbekistan.”

After decades of autocratic rule, could these constitutional reforms be the light at the end of the tunnel? Is this the democratization that regional observers and political scientists have been waiting for?

Forever Presidents

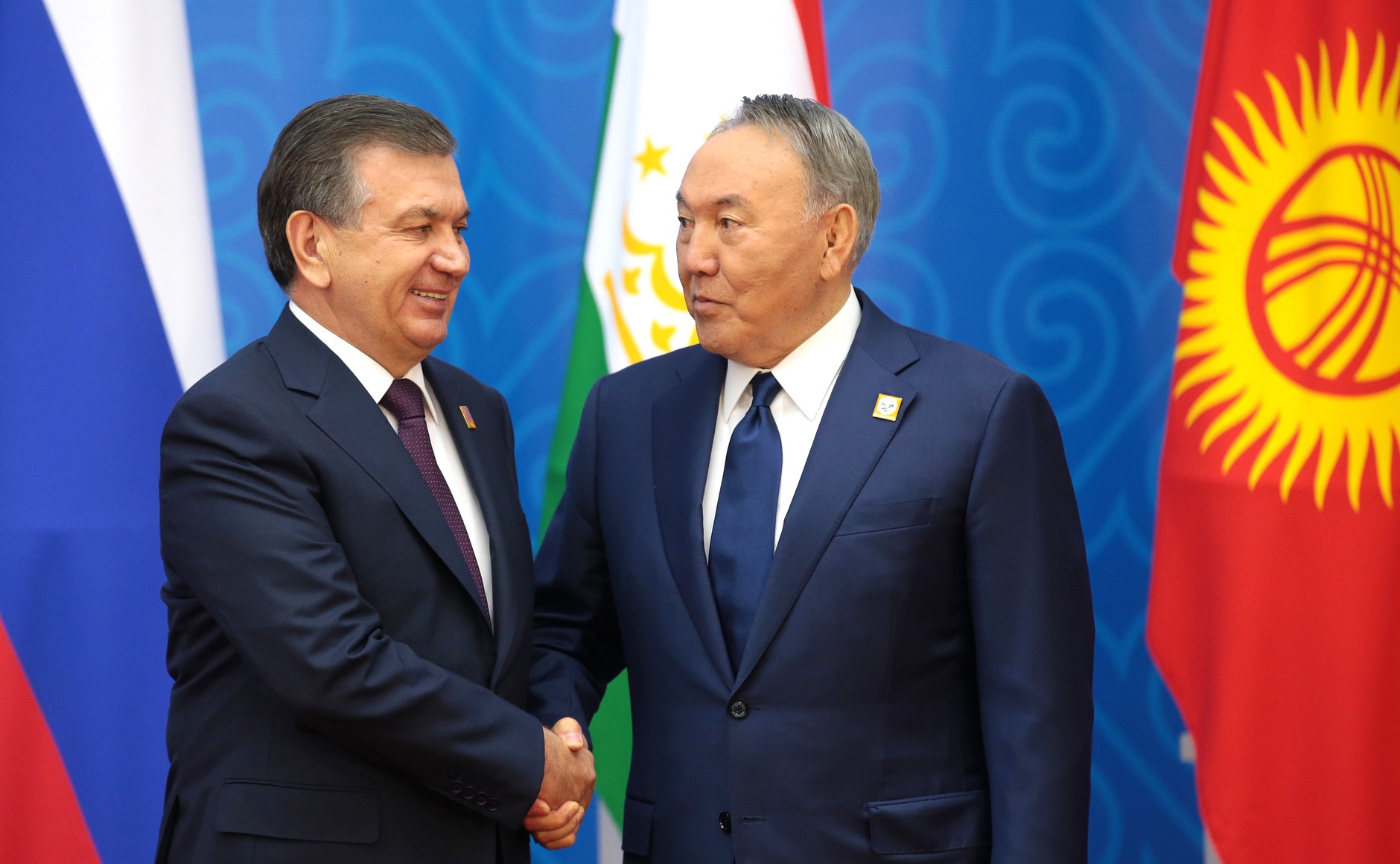

Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, in a similar fashion to other post-Soviet states, inherited their first presidents from the Soviet era. Kazakhstan’s Nursultan Nazarbayev and Uzbekistan’s Islam Karimov were both appointed to their posts as presidents of their respective Soviet Socialist Republics in the waning years of the USSR.

The two leaders quickly tossed aside Communism as a governing ideology and instead embraced nationalism as their guiding principle–one that envisioned the fate of the nation as dependent on their tenure in office.

Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan quickly adopted constitutions that closely resembled those of more established democracies. The founding documents established presidential republics, guaranteed protections for civil and human rights, and crucially included term limits for both countries’ heads of state.

Yet it seems clear that Nazarbayev and Karimov had no intentions of serving their two terms and retiring to the speaking circuit, and they both worked to circumvent the constitutional restrictions on the presidency. The recently ousted Mikhail Gorbachev had seemed to warn of what might happen if they chose to step down from power.

One model they might follow was the so-called “Niyazov method,” named after the first president of neighboring Turkmenistan, Saparmurat Niyazov. Taking on the name Türkmenbaşy (“Head of the Turkmen”), Niyazov discarded his nation’s constitution and was enshrined as “President for Life” in 1999. Niyazov held power until his death in 2006, but in doing so turned his nation into a pariah state.

Nazarbayev and Karimov preferred to chart a different path, one befitting a more cosmopolitan president who valued international perception, and they looked to other examples around them.

In the post-Soviet space, heads of state developed several institutional methods to violate the spirit of their countries’ constitutional law, while not crossing any lines de jure.

These included the “Yeltsin-Putin method,” in which a head of state facing significant legal issues when their term limits are up promotes a successor in exchange for amnesty. There was also the “Putin-Medvedev method,” in which a head of state facing constitutional term limits promotes a puppet successor to keep his seat warm until he can legally be president again.

Like Russia, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan have pioneered constitutional game-playing to ensure their leaders stay in power, or, at the very least, are immune from prosecution upon retirement.

Karimov fashioned his own method of remaining in power in Uzbekistan. After purging the nation of outspoken resistance to his rule in the first half of the 1990s, Karimov’s puppet parliament announced a popular referendum to decide on whether he would be allowed to skip the scheduled 1996 presidential election.

Karimov defended this move by citing the need to “steady the ship” in the face of supposed Islamist threats emanating from neighboring Tajikistan and Afghanistan. With a stated turnout of 99.3%, the measure passed with, officially, 99.6% of voters in favor. Karimov’s first term in office was therefore extended until the year 2000.

Only one month later, seemingly enticed by the possibility of achieving a similar success, Nazarbayev announced his own popular referendum on skipping his upcoming election, too. Lacking a more salient Islamist threat on his borders, Nazarbayev argued that he ought to stay in power without distractions so that he could focus on the nation’s economy. His victory was less impressive than Karimov’s; in Kazakhstan, only 95% of voters are said to have approved the measure.

While both presidents achieved their goal of staying in power, such blatant rule-bending did not win much praise from Western democracies, whose economic support was vital for both nations to join the global market economy. The stench of burgeoning autocracy was so strong that, in 1996, Uzbekistan’s Karimov was only able to obtain a brief face-to-face meeting with U.S. President Bill Clinton after releasing dozens of political prisoners.

In an attempt to rectify this problem, Nazarbayev fashioned a new way to prolong his tenure in office while still coloring within the lines. When Nazarbayev wanted more power, he would gain it the “right” way, and have Kazakhstan’s constitution changed to suit his wishes. Deluges of constitutional reforms passed through the legislature wrapped in the banner of “democratization,” while reforms that entrenched the autocracy were downplayed.

Karimov followed close behind Nazarbayev. Near the turn of the millennium, both countries had bicameral legislatures, regular elections for the presidency and parliament, an assortment of political parties and, at least theoretically, strong constitutions.

All of it was for show.

The Shell Game

Why would Nazarbayev and Karimov put so much effort into building the facade of democratic governance? After all, they weren’t just building Potemkin villages; they were building entire Potemkin governments.

Potemkin elections, the true results of which no one can be completely certain, must be held to staff the Potemkin parliaments. The Potemkin parliaments must be outfitted with Potemkin political parties. The Potemkin political parties must be filled with MPs and senators, as well as staffers and senior management. Constitutional Courts in both countries, whose ostensible raison d’etre is to ensure the president stays within the bounds of the law, are staffed with Potemkin justices.

All of this is done despite the head of state being legally vested with the power to essentially rule by decree. To this day, both nations’ constitutions allow for the president to unilaterally disband their parliaments for any reason. The president, and everyone else, plays the game anyway. Why?

The autocrats of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan internalized early that the baseline for meaningful “acceptance” into the international liberal community can be achieved by merely pretending to be fledgling democracies. This acceptance opens their countries up to the massive investment that the liberal democracies of Europe and North America can muster, allowing for domestic economic stability (and some money in the form of bribes to the autocrat himself).

Kazakhstan would even go the extra mile to sell its democratic facade to the United States, spending unknown sums of money ahead of its 2004 parliamentary elections to take out full-page advertisements in The New York Times, The Washington Post, and other prominent American newspapers praising its “multiparty democracy.”

All this is not to say that the strategy was an instant success. Throughout the 1990s, the United States was hardly amenable to these charades. Fresh from its victory in the Cold War, American foreign policy emphasized international cooperation and democratization.

With the understanding that the Cold War was ultimately a battle between the forces of tyranny and democracy, the United States foreign policy sector saw in its victory the birth of a new era, in which peoples the world over would cast off the yoke of dictatorship and accept liberal democracy.

To the United States, the prophesied democratization was not happening fast enough in post-Soviet Central Asia, the governing institutions of which had been easily captured by former Soviet functionaries. Throughout the 1990s, the United States had criticized both Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan for suppressing their electoral opposition, widespread voter fraud, and the reestablishing of autocracy.

The American era of democratic idealism would largely collapse along with the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001. With the advent of the Global War on Terror, the autocrats of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan—yesterday’s embarrassments—quickly became key players.

Karimov and Uzbekistan

After 9/11, Uzbekistan allowed the United States access to its Karshi Khanabad air base. In 2002, the United States and Uzbekistan signed on to a “strategic partnership” that would include American aid in the form of favorable loans, military hardware, and intelligence. In return, Uzbekistan promised to hasten its “democratization.” This process included, among other things, establishing a “genuine multi-party system” and ensuring “free and fair elections” and “the constitutional principle of the separation of powers.”

Perhaps, for a moment, there was a chance of democratization in Uzbekistan. In 2003, Uzbekistan passed a series of constitutional amendments that would devolve substantial powers from the executive branch to the legislative branch. Karimov claimed the purpose of this change was to construct a political system in which not everything depended on him. With the end of his second term in sight, Karimov may have seen his off-ramp.

That is, until the shooting started.

In 2005, in the name of anti-terrorism, Uzbek security forces gunned down hundreds of protesters in the eastern city of Andijan. The United States, likely not thrilled about losing its new best friend in the region, called for “both sides”—the Uzbek security forces and the protesters—to show restraint.

However, after being pressured by its European allies and in the wake of growing domestic disapproval, the Bush administration meekly announced its support for a United Nations-led investigation into the events at Andijan. Karimov, claiming that the United States was trying to foment a color revolution in his country, promptly kicked the Americans out of the Karshi-Khanabad airbase.

Bilateral relations between the United States and Uzbekistan would not resume for six years, when, in 2011, the Obama administration decided to end the American arms embargo on Uzbekistan, which had been initiated after the Andijan massacre.

Upon being questioned over the rationale of sending military armaments to a dictatorship with such a demonstrably poor human rights record, a senior official in the State Department answered, “I take [Karimov] at his word,” regarding the Uzbek government’s commitment to democracy.

Nazarbayev and Kazakhstan

While Karimov was playing a less-than-convincing role as a friend to democracy, Nazarbayev was hard at work trying to shore up his own goodwill with the Western liberal democracies in the first decade of the new millennium.

When it came to the War on Terror, Kazakhstan’s support for the U.S.-led intervention in Afghanistan stopped short of allowing U.S. troops in the country. Nazarbayev did not want to risk alienating his other two suitors, Russia and China.

However, Kazakhstan sent several dozen troops to support the U.S. occupation of Iraq. In exchange for their other support for U.S. operations in Afghanistan and Iraq, the United States gave Kazakhstan hundreds of millions of dollars in aid throughout the War on Terror.

Aside from playing along with the United States’ ventures abroad, Nazarbayev also saw fit to court the European democracies. His pitch was the same as it had been in the 1990s, that is, that Kazakhstan is a developing democracy and that it would be unfair to rush Kazakhs along. Of course, these excuses were being made at the same time more and more power was being amassed around the personage of President Nazarbayev.

The difference between reality and fiction seemed to matter little to the Europeans. It mattered so little that, in 2007, Kazakhstan was awarded the chairmanship of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE)—an international organization whose duties include monitoring democratic development—only months after dispensing with term limits for Nazarbayev (and him alone).

The chairmanship was a huge win. Beginning in the 1990s, Kazakhstan’s Foreign Ministry had been making its bid for the job. Chairing the OSCE, which had been criticizing his country’s elections since independence, would confer upon him and his government democratic legitimacy, both in the eyes of his citizenry and the international community.

What tipped the ball in favor of Kazakhstan’s OSCE bid was its government’s stated commitment to implementing serious democratizing reforms between 2007 and 2010, when it was set to assume the position.

In reality, the opposite occurred. By the time Kazakhstan assumed the chairmanship, the promised reforms, which included legislation to liberalize media and bring Kazakh elections in line with democratic standards, had not been implemented.

During its one-year tenure as OSCE chair, the Kazakh government continued to move in an undemocratic direction, signing amendments to the constitution that gave Nazarbayev and his family lifetime immunity from criminal prosecution and even making it a criminal offense to “damage the president’s image.” These craven autocratic measures did not make much of an impact to the voting members of the OSCE, most of which are considered democracies.

There were some limits on liberal democracies’ patience with Kazakhstan. In 2010, a supposedly grassroots effort by members of civil society started a petition calling for a new national referendum, the aim of which was to extend Nazarbayev’s presidential term until 2020, thereby cancelling the 2012 and 2017 presidential elections.

Within weeks, the petition was said to have gathered over 5 million signatories (or, one third of the entire Kazakh population). The Kazakh parliament, whether working on their own initiative or not, decided to hold a national referendum on the measure.

This turned out to be a step too far for the United States, whose Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton, communicated her concerns to her Kazakh counterpart about the “setback to democracy” such a referendum would threaten. In response, Nazarbayev promptly vetoed the referendum legislation when it reached his desk.

However, the Kazakh parliament, filled to the brim with Nazarbayev loyalists, overrode his veto. Luckily, Nazarbayev could turn to the much smaller Constitutional Council, who did him a favor and struck the referendum legislation down on a technicality. Nazarbayev, for staying true to his ostensible commitment to democratic values, received praise from the United States and the OSCE, and cruised on to a landslide victory in a snap presidential election four months later.

Exporting the Shell Game

Aspiring autocrats around the globe have followed Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan’s lead, passing constitutional amendments that increase presidential power and term longevity at the expense of their nations’ legislatures and independent judiciaries.

In 2008, Karimov and Nazarbayev publicly pushed Vladimir Putin to follow their lead and change Russia’s constitution to allow him to stay in power for a third presidential term. At that point, Putin opted instead to “pass the torch” to his Prime Minister, Dmitriy Medvedev, and return to the presidency when Medvedev’s term expired. In 2020, however, he chose another path. Russia passed a package of constitutional amendments that, among other things, cemented Putin’s right to stay in power uninterrupted until 2036.

Kyrgyzstan, once viewed as an island of democracy in a mostly autocratic region, held their own constitutional referendum in 2021 to change their country from a parliamentary system to a presidential system (i.e., to vest significantly more power in the position of president). The referendum also extended the maximum length of a president’s tenure from six to ten years.

Five years before Kyrgyzstan’s constitutional overhaul, Tajikistan held a constitutional referendum to get rid of presidential term limits entirely for its president (who has been in power since 1994).

The Heirs Today

Are today’s generation of leaders in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan following in Nazarbayev’s and Karimov’s footsteps? With Karimov dead since 2015 and Nazarbayev in retirement, much hope has been invested in the reform-oriented heads of state, and it would be dismissive to say that some genuine reforms have not been instated under their watch.

Uzbekistan after Karimov has opened itself significantly to the outside world following reforms in the business and tourism sectors. Uzbekistan also ended its notorious practice of state-sanctioned cotton slavery, for which the country’s newest president, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, has received much praise (though responsibility for the use of forced labor in cotton harvesting in the first place has not been publicly acknowledged).

Kazakhstan, for its part, has removed from its constitution very stringent protections on Nazarbayev’s post-presidential power (though this is most likely the result of an inter-elite power struggle and not an expression of democratization).

When it comes to genuine democratization, very little progress has been made beyond allowing a few more parties into each nation’s legislature. Regular citizens still do not have much of a say in who represents them in government, and incumbent presidents remain bolstered by incredibly high margins of victory at the ballot box.

The new generation of reformers is also extending their presidential terms via popular referenda and (successfully) passing themselves off as democratizers. The results of Kazakhstan’s 2022 constitutional reforms will allow its president to stay in power until at least 2029, and Uzbekistan’s president is legally able to stick around until 2040.

Some things never change.

https://eurasianet.org/kazakhstan-political-reset-or-more-old-style-authoritarianism

https://eurasianet.org/uzbekistan-competition-free-vote-to-confirm-mirziyoyevs-grip-on-power

Brumberg, Daniel. “The Trap of Liberalized Autocracy.” Journal of Democracy 13, no. 4 (2002): 56–68. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2002.0064.

Dagiev, Dagikhudo. Regime Transition in Central Asia Stateness, Nationalism and Political Change in Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. London: Routledge, 2017.

https://www.hrw.org/news/2007/11/29/kazakhstan-osce-chairmanship-undeserved

https://fpif.org/obama_to_aid_uzbek_dictatorship/

https://www.slow-journalism.com/app-issues/karimovs-bitter-harvest