Though it has been three decades since the break-up of the Eastern Bloc and the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the former Soviet republic of Moldova continues to be pulled in two directions: many want closer ties with the West while Russia continues to exert powerful influences on the small nation. This month historian William Zadeskey examines the relationship between Moldova and neighboring Romania to explore questions of political allegiance and cultural identity in this complicated corner of the world.

Both politically and culturally, Romania and the Republic of Moldova have never been closer. The partnership between Bucharest and Chișinău has grown since Russia’s invasion of neighboring Ukraine in 2022.

After Ukraine, Moldova has been the country most affected by the conflict. Since February 2022, more than 700,000 Ukrainian refugees have entered the nation of 2.6 million, with over 100,000 staying there. Russian attacks on Ukrainian civilian infrastructure have led to blackouts across Moldova, Russian missiles have violated Moldovan airspace and crashed onto its territory, and Kremlin plots against Chișinău’s Western-leaning government have led to increased political instability.

Romania, a NATO and EU member, has stepped up to help its smaller, Romanian-speaking neighbor during this time of crisis. Bucharest has provided Moldova with desperately needed energy assistance, advocated for the smaller nation within the EU, and pledged to stand with Chișinău in the face of Russian threats.

As Romanian President Klaus Iohannis promised in August 2022, “Romania will continue to be the most important supporter of the Republic of Moldova, its citizens, and its European integration.”

Iohannis also underscored Moldova’s need for continued support to U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken during a meeting in late November. In February 2023, Iohannis’s rhetoric reached new heights. After detailing Russian threats to Moldova, he proclaimed that Romania would support Moldova in “any scenario.”

All of this brings into sharp focus the question of just what it means to be Moldovan or Romanian and whether the two should unite into a single country, as they had been between 1918 and 1940.

The current partnership between the two countries has led to calls by some Romanians for Maia Sandu, the pro-EU president of Moldova, to run for the Romanian presidency in 2024. Further, the Alliance for the Union of Romanians—a far-right, populist party advocating for the unification of Moldova into Romania—performed surprisingly well in the 2020 elections.

For some, Moldovan identity was created by the Soviet Union, a process that stripped Moldovans of their “real” Romanian identity. Moldovan Sandu and her pro-EU party (The Party of Action and Solidarity, PAS) have worked to embrace Moldova’s Romanian heritage. Sandu routinely marks the Day of the Romanian Language and has banned symbols glorifying Russia and the Soviet Union.

On March 16, 2023, the Moldovan parliament took the historic step to replace the phrase “Moldovan language” with “Romanian language” in all of the nation’s laws. The two nations continue to build ties that bind them together.

The question remains, however: Is such a union between Moldova and Romania a real possibility?

While the two states have long historical, cultural, and linguistic ties, and their pro-EU governments have created a natural atmosphere for cooperation, Moldova’s development of a unique Moldovan identity under Russian and Soviet rule makes a political union unlikely. Indeed, polls tell us that Moldovans are largely against a political union, whereas Romanians generally support it.

Moldova’s Historic Lack of a Strong Romanian Identity

Scholar Benedict Anderson famously defined nationalism as an “imagined community” binding together a widespread group of people into a single national consciousness. In the Romanian case, there was no understanding of a Romanian nation until the mid-1800s.

Prior to this Romanian national awaking, the people who make up modern Romania and Moldova inhabited two principalities (Wallachia and Moldavia) and parts of Transylvania. While historical accounts indicate that the Wallachians and Moldavians spoke similar Latinate languages, shared a Dacian-Roman heritage, and had a related culture, it would be inaccurate to refer to them simply as Romanians. Such a national consciousness simply did not exist yet.

The development of national ideas differed greatly in Romania and Moldova, and this history reverberates today.

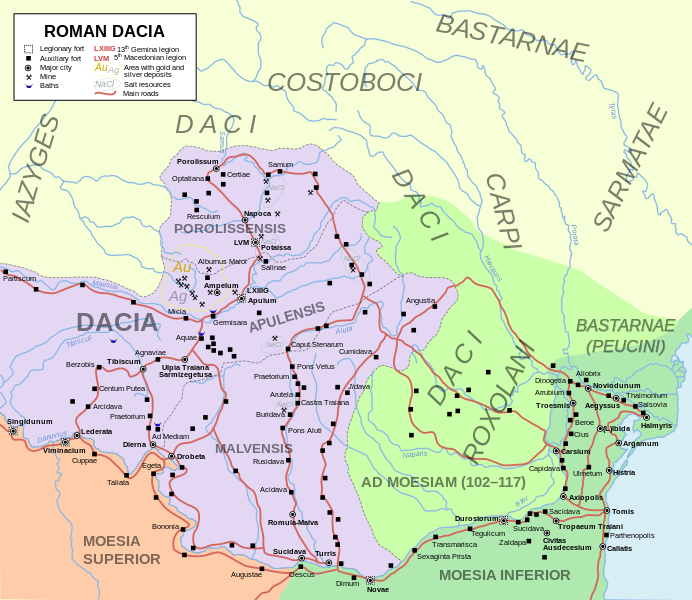

The people who today speak Romanian derive their heritage from the Dacians and Romans. The Dacians, a Thracian people who inhabited what is today southern and eastern Romania, were conquered by the Roman Empire in 106 CE. During the almost 165 years of Roman occupation, the local population was Romanized, adopting Latin and intermingling with the Roman colonists. Ultimately, attacks from outside tribes forced the Romans to withdraw in 271 CE, beginning a 600-year period of outsider rule for the Daco-Romans.

The 14th century marked the advent of two Romanian principalities: Wallachia and Moldavia (although always referred to in Romanian as Moldova, I opt to use this Russian-derived name to avoid confusion). Both were populated by Romanian speakers, while Moldavia housed a more diverse mix of Magyars, Tatars, Cumans, and Romanian-speaking Wallachians.

The two principalities gradually submitted to Ottoman rule during the 1400s and 1500s, while Transylvania’s large Romanian-speaking population came under the rule of Hungarian nobles. In 1594, Mihai Pătrașcu, voivode of Wallachia, revolted against his Ottoman overlords. By 1599, “Mihai the Brave,” was victorious and had brought Wallachia, Moldavia, and Transylvania under his rule.

The union, however, soon collapsed with the assassination of Prince Mihai by a treasonous Habsburg general in 1601. Mihai’s short reign had marked the first time that Wallachia, Moldavia, and Transylvania—roughly congruent with modern Romania and Moldova—were all united in a single political entity.

Beginning in the 1840s, Romanian nationalists portrayed Mihai’s mission as one centered on binding the Romanian nation together.

Of particular note is Nicolae Bălcescu’s seminal work, The History of the Romanians under the Voivode Mihai the Brave. Bălcescu, a soldier, historian, and leader of the 1848 Wallachian revolution, framed Mihai’s ambitions as not simple conquest but as uniting the Romanian nation.

In more recent times, the 1970 film, Mihai Viteazul (Michael the Brave) portrayed the voivode as fulfilling the “destiny” of all Romanians by uniting his divided people.

Historic sources illustrate that neither the Wallachians nor Moldavians understood themselves as part of a Romanian nation.

A Moldavian medieval chronicler, Miron Costin, described Mihai’s reign as “the cause of much spilling of blood among Christians.” A contemporary Wallachian chronicler did not even differentiate among Mihai’s enemies, writing that “he subjected the Turks, the Moldavians, and the Hungarians to his rule, as if they were so many asses.”

Lucian Boia, a prominent Romanian historian, points out that these accounts lack any mention of Romanian unification.

Today, Romanian unionists tap into this history to justify their vision of a united Greater Romania. George Simion, leader of the Alliance for the Union of Romanians, has evoked Mihai’s union in his messaging.

In a January 2022 press release titled “The Alliance for the Union of Romanians was established precisely to give a chance to the Union and National Unity!”, one AUR deputy uses Mihai’s conquests as a historical precedent, illustrating that the feeling of unity has always existed in the Romanian people.

Whether explicitly or implicitly, the historiographic characterization of Mihai as the first unifier of Romania and Moldova continues to color the thinking of Romanian unionists.

Russian Influences on Moldova

From 1812 onward, the history of modern Romania and Moldova diverged. In that year, the territory that is today the Republic of Moldova—comprising the majority of the region known then as Bessarabia—was annexed by the Russian Empire, splitting it off from the other Romanian-speaking provinces.

Over more than 100 years of Russian Imperial rule, the people of this region came to be culturally influenced by Russia. These circumstances, in part, led to the creation of a unique Moldovan identity.

Throughout the period of Russian rule, a general policy of Russification was enacted to counter the growth of non-Russian nationalism. Russians dominated the region’s urban areas, while Moldovans were largely relegated to the countryside. Thus, Russian became both the lingua franca and declared the official language. Religion also became a target of Russification.

Soon after the annexation, the Romanian Orthodox churches of Bessarabia were supplanted by the Russian variant. Ultimately, this change in religious leanings was undone in 1918 and then reversed again when the region was occupied by the Soviet Union, which quietly allowed the Russian Orthodox Church to operate.

After the fall of communism, the Romanian-led Metropolitan of Bessarabia was resurrected, and the Russian church was reorganized as the Metropolis of Chișinău and All Moldova. Modern Moldovan Christianity remains divided along these cultural lines. In a recent poll, nearly 60% of Moldovans displayed high confidence in the Russian Orthodox Church, while about 40% felt the same regarding the Romanian Orthodox Church.

While the Bessarabians confronted Russification, the Wallachians and Moldavians across the border consolidated around a Romanian national consciousness. The Russian-dominated Bessarabians missed numerous crucial events that forged the Romanian nation: the 1821 rebellion against the Ottomans, the adoption of the Romanian language, the creation of the first Romanian nation-state in 1859, the founding of the Romanian kingdom, and the 1877-78 war for independence.

The people of Bessarabia came to be influenced by Russian culture and lacked a strong connection to the newly defined Romanian nation.

Towards a Unique Moldovan Identity

Following over 100 years of Russian rule, the Sfatul Țării (National Council), declared Bessarabia’s independence on December 2, 1917. The council voted to unite with Romania three months later.

Within Greater Romania, Bessarabia was ruled more like a colony than an equal part of the state. Romanian authorities asserted heavy-handed authority, and the secret police aggressively searched out suspected Bolshevik agents.

Culturally, the Romanian introduction of the Gregorian calendar and the Latin alphabet was a point of tension for Bessarabians accustomed to the Russian Julian calendar and Cyrillic.

One Bessarabian writer summed up the local feeling as follows: “We joined the Romanians, we weren’t supposed to have been conquered by them.” In the geopolitical space, Bessarabia’s status was not settled between Romania and the newly empowered Soviets.

During the same period, the Soviet Union established the Moldovan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (MASSR), a small sliver of land on the eastern bank of the Dniester River (today’s Transnistria).

Soviet officials and scholars crafted a unique identity for the Moldovans. Linguists developed an independent Moldovan language, written in the Cyrillic script, drawing on Russian cognates and separate from “bourgeois” Romanian. The Soviets founded a Moldovan-language publishing agency and mandated the language’s use throughout the MASSR.

One Soviet official employed eugenic principles to argue that Romanians and Moldovans had differing “cranial structures” and separate temperaments.

This Soviet-made Moldovan identity ascended to the mainstream after Bessarabia’s annexation on June 28, 1940. The legacy of Soviet Moldovanism continues to affect Moldova-Romania relations.

Post-Soviet Moldova has been ambiguous about the cultural distinctions (or lack thereof) between the two cultures and languages. For instance, Moldova’s 1991 declaration of independence called the nation’s language “Romanian” while the 1994 constitution labeled it Moldovan. Moldova’s 1995 national anthem, “Our Language,” is enigmatic about what the language is actually called. Moldovan political leaders have tended to embrace Moldova’s Soviet and Russian heritage while simultaneously advocating for Moldova’s unique identity.

Despite President Sandu’s recent efforts to promote Romanian culture, recent polling indicates that Moldova’s history of association with Russia and the unique, Soviet-inspired Moldovan identity still affects Moldovans’ cultural attitudes.

A February 2023 survey by Chișinău-based iData found that only 32% of Moldovans felt more culturally attached to Romania, while 28% related to Russia. A plurality, about 40%, had no cultural attachment to either Romania or Russia. Further, less than 6% of the survey’s 1040 respondents identified as ethnically Romanian, compared to 74% who considered themselves to be Moldovan.

The history of Moldova’s loose connection to the Romanian nation and the effects of Russian and Soviet rule on Moldovans’ cultural identity have created a situation wherein many Moldovans do not consider themselves Romanians. This history limits the prospects of a political union.

Unionism Today

As the Soviet Union collapsed, pan-Romanian forces came to power in Moldova, initiating an ill-fated foray into unionism that reverberates today. Founded in 1989, the Popular Front of Moldova (FPM) supported democratization, perestroika, and Moldovan nationalism. These positions generated a great deal of support for the FPM.

Slowly, however, the organization adopted a pan-Romanian ideology. First, the group demanded that the MSSR recognize the “Moldo-Romanian linguistic unit,” a rejection of the Soviet Moldovan identity. The FPM believed this manufactured nationality was a Soviet tactic to “de-nationalize the Bessarabian Romanians.” Such rhetoric still echoes today. After coming to power in the March 1990 elections, the FPM embraced Romanian culture by adopting the Romanian flag, national anthem, and language.

The Popular Front government also made the consequential decision to discuss and even openly support a union with Romania.

At the Second Congress of the Popular Front of Moldova in July 1990, Iurie Roșca, a staunch pan-Romanianist and member of the FPM leadership, openly called for a union with Bucharest. Ultimately, this talk of union led to revolts in Transnistria and the Gagauz region and contributed to the fall of the FPM government. In fact, only about 3.9% of Moldovans supported joining Romania in 1990.

Support for a Moldo-Romanian reunion is limited mainly to Romania. A January 2023 study conducted by a Romanian think tank concluded that 75% of Romanians support a political union with Moldova.

However, an iData poll from February 2023 found that 60% of Moldovans were against uniting with Romania. This lack of support is unsurprising given Moldovan’s cultural and religious leanings. Furthermore, Moldova would actually become less secure if a political union was officially proposed.

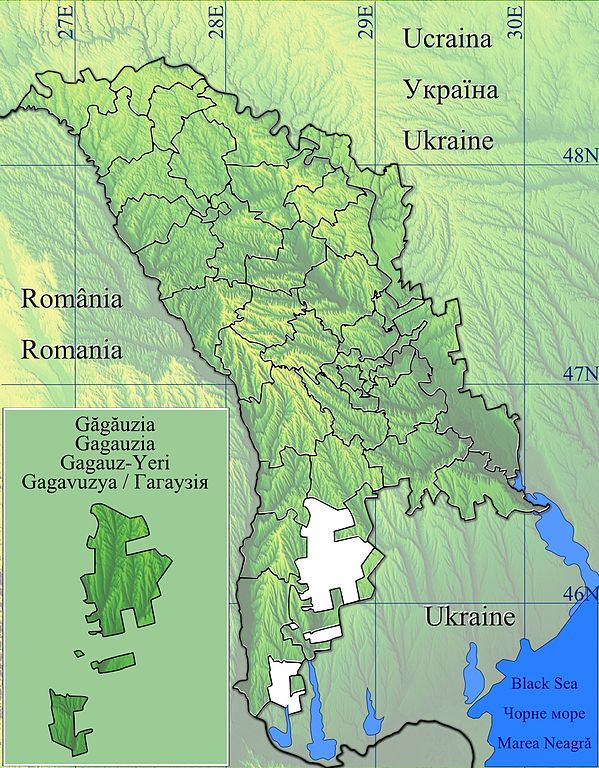

Although some may consider a Moldovan-Romanian union as a simple way for Moldova to join the EU and NATO, even the prospect of a union would likely ignite political instability across Moldova—particularly in Gagauzia and Transnistria.

The southern Gagauzia region is home to the Gagauz people, a Turkic and Christian ethnic group. In addition to their native Gagauz language, the people of the region largely use Russian rather than Romanian. In the early 1990s, the Gagauz feared that the rampant pan-Romanian attitudes in Chișinău could infringe on their cultural and linguistic rights.

As a result, they formed the Gagauz Republic and declared their independence from Moldova on August 19, 1990. Ultimately, the dispute between Gagauzia and Chișinău ended peacefully in 1994 with the region’s reintegration into Moldova.

However, in the law granting the region special autonomy, Gagauzia retained the right to succeed from Moldova “in the event of a change in the status of the Republic of Moldova as an independent state”, i.e., if Moldova were to join Romania.

Thus, real talk of a union would ignite a political crisis between Chișinău and the Gagauz, who tend to support the Kremlin. The pro-Russian, breakaway region of Transnistria would also greatly complicate any proposal to unify.

Like the Gagauz, the Russians and Ukrainians of Transnistria feared that their language rights would be restricted by the pan-Romanian forces in Chișinău. The region declared its independence on September 2, 1990.

After a short but bloody war with Moldova in the summer of 1992, and with the protection of Russian “peacekeepers,” Transnistria has retained its status as a de facto independent state. As Chișinău still considers the region as part of the Republic of Moldova, talk of a union would reawaken this frozen conflict.

Furthermore, Romania, a NATO member, would be drawn into the Transnistria dispute. Such a situation would increase the likelihood of direct confrontation between NATO and Russia.

While cultural differences and political realities keep Moldovan-Romanian unification unlikely, the political relationship between the two Romanian-speaking nations has flourished under Presidents Sandu and Iohannis and will likely continue to strengthen.

A Flourishing Relationship

While a political union is unlikely to happen anytime soon, Moldova-Romania relations have strengthened significantly of late, and the two nations now cooperate at the highest levels. Bucharest’s and Chișinău’s political and economic partnership likely will continue to grow.

Sandu’s election in 2020 realigned Moldovan foreign policy towards Romania, a major departure from the anti-EU, pro-Russia position of her predecessor, Igor Dodon. While Dodon never once traveled to Bucharest, Sandu’s first foreign trip was to the Romanian capital. Romanian President Iohannis was both the first foreign leader to congratulate Sandu and visit her in Chișinău.

The two presidents have held at least seven bilateral meetings in the past three years. In their first meeting in late 2020, Iohannis reaffirmed his nation’s commitment to “remaining the most sincere supporter” of Moldova.

Romania’s actions have certainly lived up to this pledge, as demonstrated by Bucharest’s vaccine donations, assistance in integrating Moldova into the EU, and crucial natural gas provisions.

In May 2021, Romania donated 100,000 coronavirus vaccines to their smaller neighbor. Romania’s outspoken advocacy for Moldova also helped Chișinău achieve EU candidacy status in June 2022. During a March 23, 2023, meeting with Moldovan Prime Minister Dorin Recean, Romanian PM Nicolae Ciucă promised to continue assisting Moldova’s EU aspirations by using all the knowledge Romania has accumulated in its dealings with the economic bloc.

Romanian energy assistance has been particularly helpful in staving off the crisis brought on by Gazprom’s October 2022 threat to cut natural gas shipments to Moldova by 30%. Before the Romanian assistance, Moldova lacked energy security since it relied on the Russian state company Gazprom and energy plants in the pro-Russian Transnistria region.

Since December 2022, Romania has provided natural gas to Moldova through the newly opened Iași-Ungheni Pipeline. With the goal of bolstering energy security for Moldova and Eastern European, Prime Minister Ciucă travelled to Egypt in early February to increase gas transportation between Bucharest and Cairo. Concurrently, the Romanian state-controlled gas company Romgaz, has worked to increase gas supplies from Azerbaijan.

In fact, thanks to the Romanian assistance, Moldova’s Minister of Energy recently said that Moldova had not paid for or received any gas from Gazprom since December.

President Iohannis has forcefully pledged to defend Moldova from Russian plots to sow instability and topple the Western-leaning government.

The Kremlin has undertaken a coordinated campaign to destabilize Moldova. On February 4, 2023, Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov warned that Moldova may become the “next Ukraine.”

Soon after, President Sandu confirmed statements by Volodymyr Zelensky that Moldovan individuals had been coordinating with Russia to launch a violent coup d’état. Six days later, Prime Minister Recean corroborated reports that Russia had plans to capture Chișinău airport. Further, U.S. intelligence determined that Moscow organized protests in Moldova to bring down the government.

Just two days after the American briefing, the Șor Party held protests nationwide. Local police revealed that Russian nationals had been paid to travel to Moldova and foment unrest. A man with ties to the Russian private military company Wagner was arrested at the airport.

Romania’s NATO commitments make it unlikely that Romanian troops would defend Moldova in the event of a Russian attack, but Iohannis’s pledge to support Moldova in “any scenario” may make the Kremlin think twice. Romania’s support for the Moldovan government brings stability in the face of the Kremlin’s destabilization efforts.

Whatever the future brings, it is certain that Romania’s help has ensured Moldovan energy security, furthered Moldovan hopes of integrating into Europe, and provided political stability during a time of deep instability in the region.

Europe's Leaders Meet in Russia's Shadow, Politico, by Suzanne Lynch, Clea Caulcutt, and Gabriel Gavin

Romania Gets Moldova (and the EU Doesn't), Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA), by Hugo Blewett-Mundy

Overcoming EU Accession Challenges in Eastern Europe: Avoiding Purgatory, Carnegie Europe, by Kataryna Wolczuk

Ilan Shor: The Kremlin's New Man in Moldova, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty Moldovan Service, by Tony Wesolowsky

Meet the graffiti artist-turned-MP who wants to see Moldova and Romania become one country, Euronews, by Orlando Crowcroft

The Moldovans: Romania, Russia, and the Politics of Culture by Charles King