Peru is undergoing agrarian reform. Again. In this essay, historian Taylor Cozzens looks at the long history of agrarian politics in Peru, examining both the domestic and international dimensions of growing food in this Andean nation.

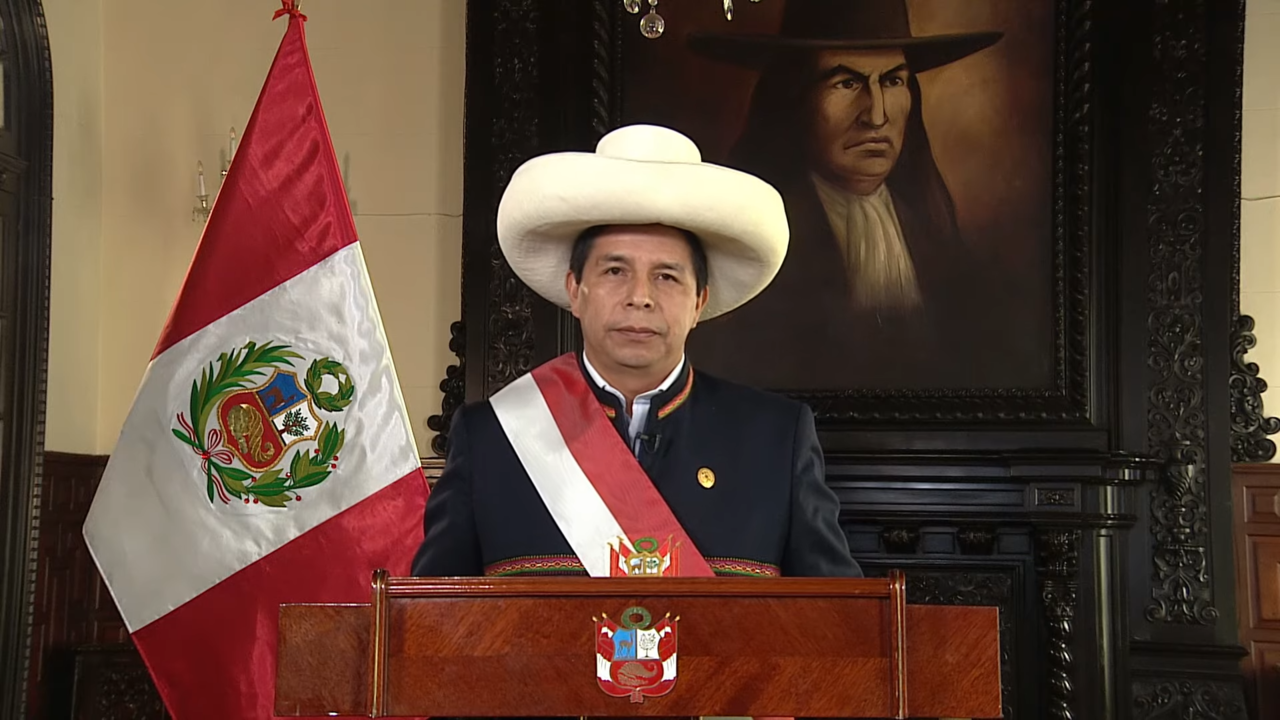

In recent years, Peru has focused substantial efforts to improve agricultural output and efficiency, especially for small farmers who have suffered for generations under the Peruvian systems of exploitative land distribution. In the fall of 2021, then President Pedro Castillo, formerly a schoolteacher from the rural Andes, began what his administration called a “Second Agrarian Reform.”

This program, he explained, would “give tools and technology to small farmers to improve their productivity and the conditions they live in.” For the brief period that he served, Castillo put this plan into practice by giving tractors to organizations of small farmers in several Andean states.

These innovations in agriculture included several well-funded international programs to share technology with small farmers and rural residents. In 2021, a diverse group of research institutions formed a consortium known as PERU-Hub. Participants included Peru’s National Agrarian University-La Molina, the University of Oklahoma (OU), Utah State University, Purdue, and the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) in Colombia.

As director Hugo Villachica declared, the group trains “farmers, women, and indigenous communities in the use of improved technologies in current and new crops, in food transformation … [and] in marketing” with the goal of “improving agricultural productivity and profitability.”

Aside from PERU-Hub, research teams from OU recently completed the first phase of collaborative projects with counterparts from the National University of San Augustín (UNSA) in Arequipa. One project, for example, will simulate the effects of climate change on future water availability in the Arequipa region.

Five hours eastward into the Andes, in the city of Puno, U.S. researchers have begun working with the National University of the Altiplano (UNA) to design an insulated, energy efficient house for the highlands of Puno (4000-5000 meters above sea level) using local materials.

Still, Castillo’s promise of a second agrarian reform brought back unpleasant memories. While many people welcomed the government’s initiative to help small farmers, the name of the program caused them to scratch their heads.

The story of Peru’s first agrarian reform in the 1960s does not have a happy ending. The failures of those earlier efforts—with their focus on land redistribution, cooperatives, and technology transfer to small farmers, along with requests for international assistance—offer essential context for today’s renewed innovation projects.

The Hacienda System

This story begins with the two main actors in rural Peru during much of the 19th and 20th centuries: haciendas and communities. A product of colonization, haciendas were estates that generally held the most fertile and best-watered farmland. They also boasted the finest agricultural technology, including machinery and selectively bred livestock.

Communities, by contrast, had roots in precolonial societies. Over time they had been pushed onto poorer and smaller tracts of land. Community members lived mainly off subsistence crops, had limited access to education, and often worked on haciendas as colonos (tenant-peons), pastores (sheepherders), muleros (muleteers), and obreros (laborers).

Hacendados (hacienda owners) frequently had friends in the government. In remote areas, where the state had little presence, hacendados practically were the government. Notably, too, they and their allies generally considered themselves to be white, regardless of actual skin color, while they considered community members to be Indigenous and backward.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, a relatively weak Peruvian state allowed hacendados to expand their borders and press further into the communities. A mid-20th century population boom added to this pressure.

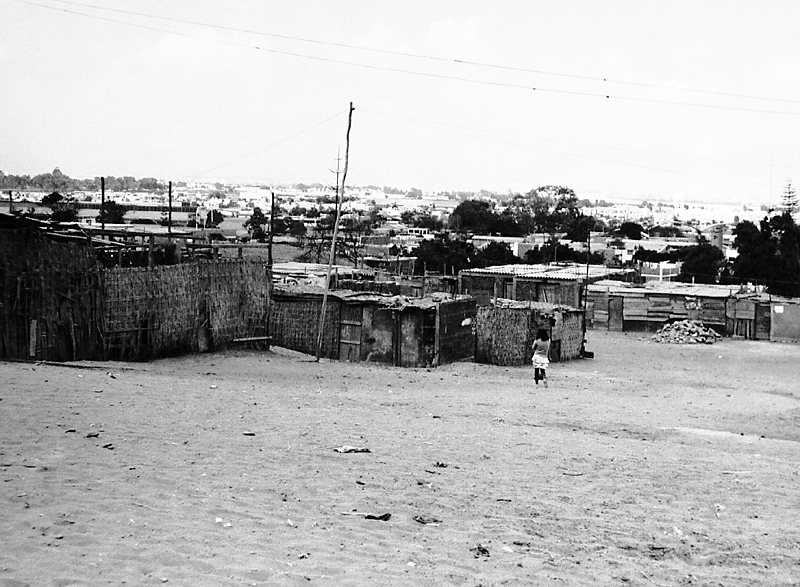

From 1940 to 1980, the Peruvian population increased from 6.2 to 17 million. Yet the rugged topography of the Andean highlands, especially the constricted spaces that communities inhabited, offered no additional room to farm. Consequently, the 1950s saw unprecedented migration to urban centers, especially Lima, and the growth of barriadas (neighborhoods of ad-hoc shelters on the cities’ outskirts).

The 1950s also saw an increase in conflicts between landowners and communities. In one such conflict in the central Andean state of Junín, members of the community of El Tingo wrote the president, Manuel Prado Ugarteche (1939-1945, 1956-1962), to express their grievances.

“These lands were [once] inhabited by our ancestors,” they wrote. Yet during the colonial era, the King of Spain had granted the lands to Spanish military officers. “[W]e were reduced to a condition of servitude.”

“Over the years, the advances of the republic have not mitigated the condition of servitude in which our ancestors lived, and which continues in us.” Hacendados, they added, had always stuck to “giving orders regarding the planting, tending, and harvesting of the crops, without sharing the slightest bit of agricultural knowledge … tak[ing] the fruits of our labors with them.”

Attempting Reform: Land or Technology

At this point in the story, small farmers in the Andes had little land, hardly any agricultural machinery, and few options for recourse. Government officials and some universities acknowledged the inequality. President Prado, for his part, formed the Commission on Agrarian Reform and Housing in 1956 ostensibly to study land redistribution options for Peru.

Influenced by hacendados, however, the commission concluded that land redistribution was not the answer. Rather, as its final report stated, the government’s efforts should be focused on “increasing cropland [through irrigation] and elevating productivity through technical, economic, and social assistance.” In essence, the state decided to give communities aid but leave the haciendas intact.

This idea underpinned Cornell University’s applied anthropology project in the community of Vicos in the state of Ancash in the 1950s. With the right agricultural technology and training, researchers believed, communities could produce more food on their limited land and increase overall prosperity, rendering land reform unnecessary.

While the Cornell anthropologists were sincere, their approach reinforced existing inequalities more than reforming them. After all, it demonstrated considerable deference to the haciendas, which still controlled the most fertile farmland, monopolized the agricultural technology, and, in some cases, abused Andean communities with impunity. Moreover, Vicos was just one Andean community among hundreds. None of the others received the same kind of attention from foreign researchers.

Communities, however, were mobilizing. In hundreds of cases from the late 1950s to the early 1960s, they moved their livestock and people onto hacienda lands in a form of nonviolent resistance. Such invasions forced officials to recognize that the Vicos approach was inadequate.

In 1964, following the invasion of the hacienda Tucle by the community of Huasicancha in Junín, the government commission observed that “given the frequency … of campesino [small farmer] unrest in our country, we have no choice but to reflect seriously on the causes…. Let’s imagine a seed in a small pot,” it continued. “The seed sprouts, takes roots, [and] these roots grow, while the pot remains the same. The moment comes when the [growing] roots no longer fit in the pot; they break it…. Does not the same thing occur in human societies that are rapidly growing?” The imminent fracturing of the social system, the commission concluded, “proves the need for [change].”

In the mid-1960s, President Fernando Belaúnde Terry (1963-1968, 1980-1985), who had campaigned on a promise of land reform, made only token efforts to expropriate some hacienda lands.

As the presidential election of 1968 approached, more land invasions appeared on the horizon, as well as a possible victory of Victor Raúl Haya de la Torre. Haya was the founder of the American Popular Revolutionary Alliance (APRA), which had, in decades past, purported to spread the Mexican Revolution to the rest of Latin America.

A Revolution from Above?

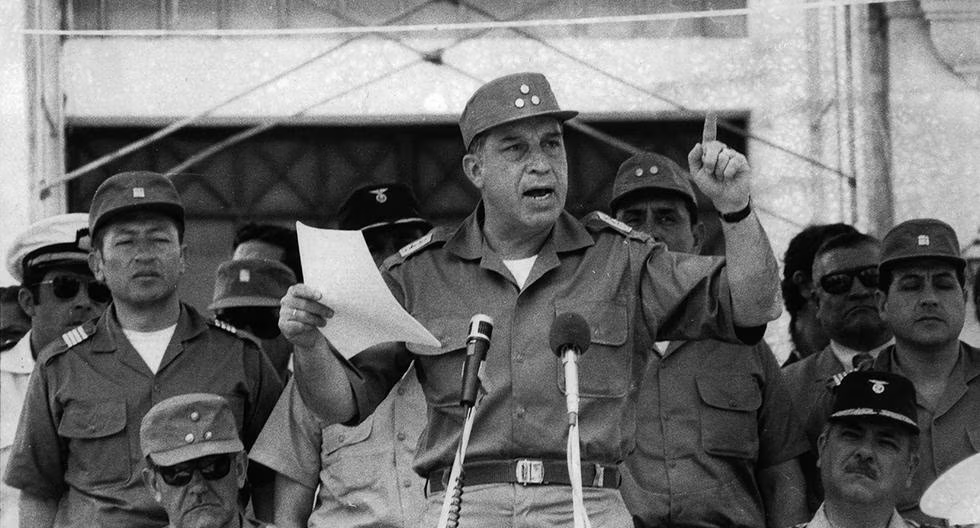

Before the election occurred, however, the Armed Forces under General Juan Velasco Alvarado took power in a bloodless coup. The Peruvian military had a history of intervening in national politics to preserve stability and the status quo, yet the 1968 coup was different.

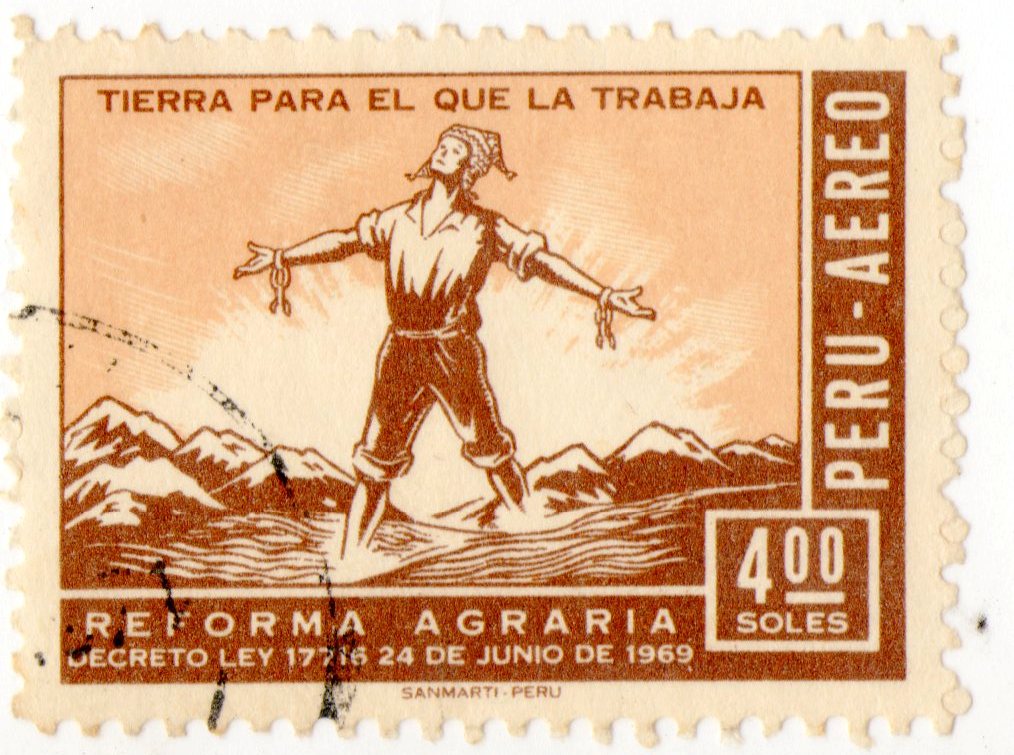

In this case, Velasco and his generals saw themselves as the nation’s only hope of stability and reform. Their “revolution from above,” as it has been called, began with expropriation of hacienda lands and the formation of agrarian cooperatives for campesino communities.

In Velasco’s vision, these steps would make possible greater agricultural production and prosperity in rural Peru.

As one cabinet member declared at the expropriation of the hacienda Chucarapi in Arequipa, “Agrarian reform, the first and great structural change in the Peruvian revolution … is the cornerstone of our new society. By establishing that the land is for those who work it, [we] stamp out, once and for all, injustice in Peruvian agriculture and lay the foundation for [our nation’s] future development.”

Critics frequently portray Velasco as a kind of agrarian Santa Claus, a demagogue who cared only about giving away land but did not understand the parallel need for training and technology.

But in its 1969 development plan, his administration stated, “Since agriculture and livestock are the most important economic activities of the campesino population in the sierra and highlands of Peru, it is indispensable that we provide appropriate technical assistance … through instruction of improved … methods, the use of improved seeds, fertilizers, insecticides, fungicides … etc.”

In 1970, Velasco sent J. Roger Arroyo, head of the Office of Agricultural Research, on a transnational tour to study agricultural innovation in Colombia, Venezuela, Costa Rica, Mexico, and the United States. The military government also signed an agreement with the International Wheat and Corn Improvement Center (CIMMYT) in Mexico.

Through such agreements, the administration declared, “we [will] address our agrarian problem. On one hand, [we have] agrarian reform, which is in essence social justice. On the other, [we will] introduce modern technology in order to achieve what some have called the ‘Green Revolution.’”

Looking for International Help

In further pursuit of green revolution, in 1971 the military government signed an agreement with North Carolina State University and the U.S. government to create the International Potato Center in Lima. Designed to develop high-yielding, blight-resistant potatoes and tuberous roots, this institution became an important node in the growing transnational network of institutions, which included CIMMYT in Mexico and CIAT in Colombia, dedicated to increasing agricultural productivity.

In each case, sponsors in the Global North sought to boost food production in nations of the Global South with the goal not only of increasing prosperity but also, in the context of the cold war, reducing the appeal of violent, communist-inspired revolutions.

Outside Lima, Velasco launched the large Majes-Siguas irrigation project, which was designed, as the Minister of Agriculture explained, to create 10,000 “high-production farms” in the desert plains of Arequipa and “provide opportunities for settlement, electricity, and wealth for the campesinos of the area.” The future of irrigation in Arequipa is now a focus of the OU-UNSA team that is modeling the effects of climate change in the region.

For the neighboring state of Puno, Velasco’s administration signed an agreement with New Zealand to find nutritious grass varieties that could thrive at high altitudes, improve the diets of sheep and cattle, and increase local milk, meat, and wool production.

These are only some examples, yet they underscore the Velasco administration’s goal of using agricultural technology to benefit the nation’s small farmers.

Cooperatives Instead of Haciendas?

Just as important was the administration’s vision for the cooperatives that it established in the place of the haciendas. In theory, these cooperatives would lead agricultural innovation by using the infrastructure, machinery, genetically improved livestock, economies of scale, and even, in some cases, the former managers of the haciendas.

Unfortunately, this vision did not materialize. For one, most Andean communities did not really want the cooperatives, which they saw as glorified, state-supervised haciendas. As the invasions of the previous decades had demonstrated, what they wanted and needed most was their land and the chance to farm it for themselves. The cooperatives did not satisfy this desire.

Regrettably, too, many cooperatives struggled to be productive. During the 1970s, national production of nearly all crops dropped. Despite their initial focus on technology, Velasco and his administrators spent most of their energy on land expropriation and adjudication, and they never fully reached the crucial step of sharing new technology with small farmers.

In some cases, they did not even explain clearly how the cooperatives were supposed to work. As one spokesperson in Cuzco indicated in 1974, “Our record books are all blank because we do not know how to write …. [W]e need training. We don’t understand what a cooperative is, nor do we understand its functions. In this condition, how are we supposed to operate?”

While Velasco’s policies clearly had shortcomings, those of his successors did not help. General Francisco Morales Bermúdez (1975-1980), a former minister and leader of a more conservative faction of the military, ousted Velasco in 1975 and moved the government away from land reform. Fernando Belaúnde (1963-1968), reelected in 1980, distanced himself even more from Velasco’s policies.

Both cooperatives and communities felt forgotten.

As 29 delegates from six cooperatives in Ayacucho wrote in 1986, “When the government of General Velasco issued [agrarian reform] law 17716, we thought at the time that it was good because they expelled the gamonales [all-powerful landowners] and gave us technical support and credit. But that lasted only a short time. With the government of Morales Bermúdez everything changed; they withdrew the [agricultural] technicians and all the aid and left us in a state of complete abandonment. And with Belaunde things were even worse.”

Facing the lack of farmland, the cooperatives’ lack of productivity, and the government’s seeming indifference, communities turned to their quintessential method of protest: invasions.

They moved onto the cooperatives just as they had moved onto the haciendas. In so doing, they initiated messy legal and social processes of “restructuring” and “parcelization,” which made it harder for the government to share technology with small farmers.

Armed Conflict

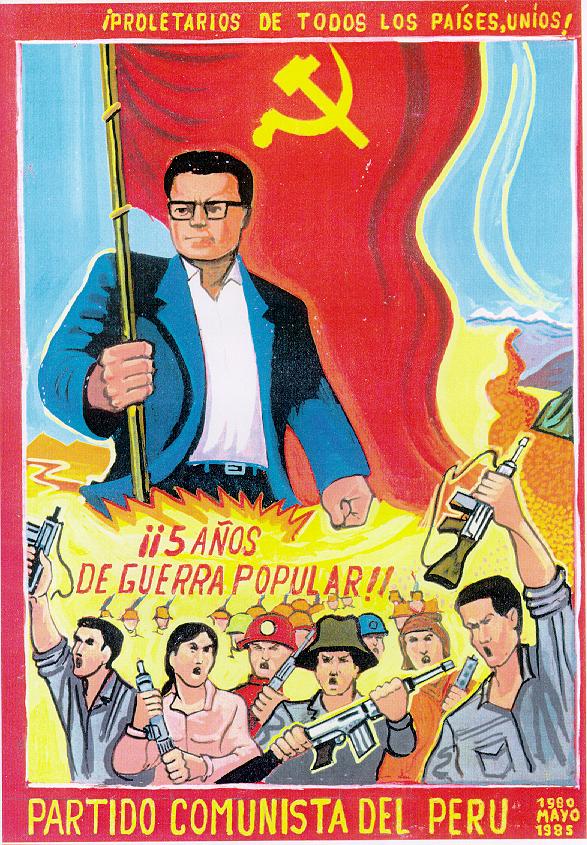

Meanwhile, another set of actors entered rural Peru: armed insurgents.

Throughout the decade, cadres from the Maoist group known as the Shining Path began arriving in communities across the Andes to recruit, demand resources, indoctrinate, and intimidate. They also began a campaign of destruction designed to wipe out the old in preparation for the new.

During this time, a smaller and slightly less radical armed group known as the Tupac Amaru Revolutionary Movement (MRTA) also began operating in Peru.

One of the main targets of these groups were cooperatives, which they saw as bastions of capitalism and inequality. Mimicking the “black harvests” of the Chinese revolution, they plundered livestock, burned installations, and executed administrators, researchers, and veterinarians.

In one livestock cooperative in Junín, armed groups killed 11 employees and caused $7 million in damage. In Puno, they threatened and drove one cooperative’s talented administrator out of the region.

They also used extortion.

In 1993 the director of a different cooperative in Puno received a letter from the MRTA. “Up until now, you all have given no thought to your poor, exploited partners,” it read. “You all continue drinking the blood of the company’s workers. Perhaps you all think of yourselves as great gamonales…. Soon we will wipe out all these evils with no respect for life.” Yet for now, the letter concluded, we will leave you alone in exchange for food and cash.

Facing nonviolent but forceful invasions from neighboring communities, as well violent attacks from armed groups, many cooperatives during the 1980s ceased to exist. During these same years, armed groups also targeted agricultural professionals and research stations throughout rural Peru. Overall, their impact on agricultural innovation was considerable.

For their part, the Peruvian military and police were slow to respond to the Shining Path and MRTA. When they did, they launched a brutal and often indiscriminate counter-terrorism campaign that accounted for nearly half of the 70,000 total deaths.

When the military arrived in a region, communities found themselves, as one NGO put it, caught “between two fires.” Ultimately, however, organized community resistance, both in collaboration with the military and independent of it, contributed immensely to the defeat of the armed groups in the 1990s.

Legacies

Despite the discouraging end of many cooperatives, land reform also mattered because it prompted other institutions, such as universities, to work more directly with small farmers. Haciendas were no longer around to monopolize technology. For example, from the 1970s onward, the Cereals Program of the National Agrarian University operated experimental stations in Andean states such as Ancash, Junín, and Puno.

With funding from Peruvian beer companies, the agronomists brought high-yielding wheat and barley seeds from CIMMYT and crossed them with local varieties to create hybrids that could resist the yellow rust and other conditions of high-altitude environments. They worked with communities to test new seeds on their land.

By the 1990s, despite threats and attacks from armed groups, the Cereals Program had found several high-yielding barley varieties for the highlands. By the aughts, it found some high-yielding wheat varieties as well. Program directors hoped that communities could use these varieties to produce grains for national markets and thereby increase income levels and reduce the nation’s dependence on imports.

In most cases, however, suppliers in Lima continued importing grains from abroad. In many communities, therefore, the new high-yielding seeds contributed only to subsistence agriculture. Over time, too, the genetically modified seeds became increasingly expensive and, without government aid, inaccessible to small farmers.

Another university actor during this time was the Crop and Soil Science Department of North Carolina State University. Funded by USAID, these soil scientists set up an experimental station in the Amazonian region of Yurimaguas, Loreto to find fertilizer combinations that could make the soils of the area more productive.

In most cases, however, small farmers demonstrated little interest in the new fertilizer formulas, perhaps because of the costs, and the Peruvian government did relatively little to promote the soil scientists’ vision for agriculture in the region.

By the mid-1980s, enthusiasm among NC-State faculty members for the project was waning, and the department struggled to find individuals willing to relocate to the Peruvian Amazon. Although in this case armed groups did not attack the research station, feelings of insecurity because of the conflict may also have discouraged the soil scientists from North Carolina.

Today, as national governments and institutions abroad revisit the idea of transferring technology to Peru’s farmers, they would do well to remember that some questions remain from recent innovation and extension efforts in rural Peru.

For example, how can such institutions work with small farmers rather than imposing an outside vision on them? How can they ensure that technology reaches these farmers and remains financially accessible? Finally, how can innovation remain sustainable when project funding or researcher enthusiasm wane?

Raúl Asensio. Breve historia del desarrollo rural en el Perú, 1900-2020. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 2023.

"University of Oklahoma Strengthens Latin American Sustainability through $15 Million PERU-Hub." Vice President for Research and Partnerships: The University of Oklahoma, May 18, 2022. https://www.ou.edu/research-norman/news-events/2022/ou-strengthens-latin-american-sustainability-through-15-million-peru-hub.

"Segunda Reforma Agraria," Ministerio de Desarrollo Agrario y Riego: Peru, 28 de agosto 2023. https://www.gob.pe/institucion/midagri/campa%C3%B1as/6052-segunda-reforma-agraria.

The Peculiar Revolution: Rethinking the Peruvian Experiment under Military Rule. Edited by Carlos Aguirre and Paulo Drinot. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2017.

Enrique Mayer. Ugly Stories of the Peruvian Agrarian Reform. Durham: Duke University Press, 2009.

Realidad del campo peruano después de la Reforma Agraria: 10 Ensayos Críticos. Editado por Francisco Moncloa. Lima: Centro de Investigación y Capacitación, 1980.