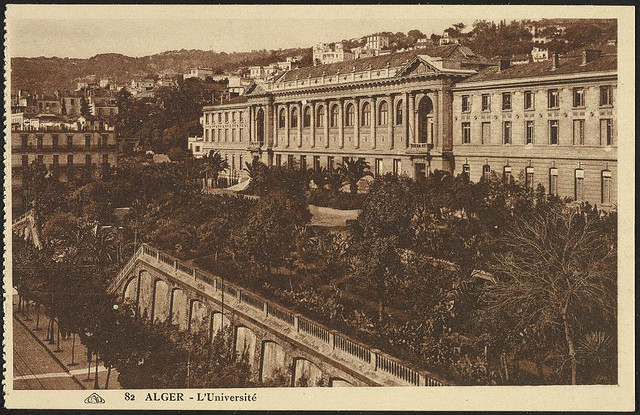

On June 7, 1962, members of the Secret Army Organization (Organisation de l’Armée Secrète, OAS), a far-right French terrorist group, detonated three phosphorous bombs at the University of Algiers. By 12:30pm, the main building of the university was engulfed in flames, lighting up the skyline of downtown Algiers. Firefighters managed to subdue the flames by 2:30pm, but the arson left significant damage.

As university employees began to sift through the wreckage, they took stock of the destruction. The ceiling of the main university building was gone, and its interior had suffered substantially from the fire.

And yet, the most significant damage was not to the building itself, but what it contained: the university’s library. Hundreds of thousands of books, periodicals, and manuscripts had become fuel for the flames.

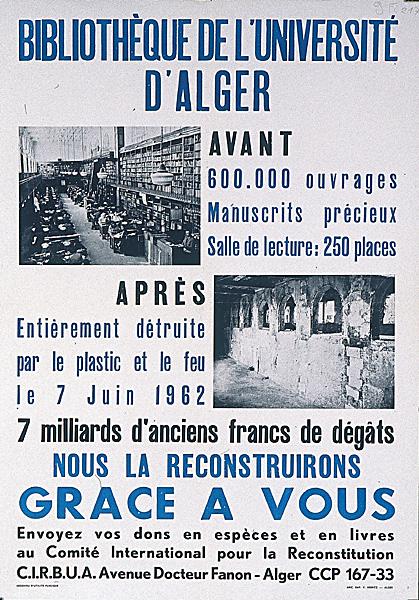

Newspapers around the world initially reported that the entirety of the library’s collection—amounting to some 600,000 works—was burned, including irreplaceable original Arabic and Latin manuscripts that were an essential part of the cultural heritage of Algeria, Africa, and the Mediterranean World.

While these estimates were later revised in light of works that could be salvaged, the final tally remained a staggering 385,000 works destroyed, including 250,000 MA and PhD theses, 2,000 manuscripts and ancient books, and over 1,000 periodicals.

The OAS’s attack on the University of Algiers library was part of a last-ditch effort of terrorism to protest Algeria’s eminent independence from France. French colonialism in Algeria began in 1830, when France invaded Algeria and defeated the Ottoman ruler. Over the nineteenth century, the French military progressively conquered indigenous Arab and Berber Algerians and took their land.

Over the same century, the French government declared that Algeria was an integral part of French territory and declared European residents who settled there were French citizens. These measures led many Europeans in Algeria and French nationals to view Algeria as not just a colony of France, but as France.

In response to French colonial oppression, on November 1, 1954, a group of Algerian nationalists organized as the National Liberation Front (Front de Libération Nationale, FLN) and declared a war for Algeria’s independence.

After six years of fighting, characterized by guerrilla warfare, torture, and violence against civilians, the French government and the FLN finally agreed to a ceasefire on March 18, 1962 and planned for public referendums on Algerian independence to take place in France and Algeria in the coming months.

It was in opposition to France’s decision to put up Algeria’s future to a vote that the OAS launched a last-ditch scorched earth campaign, bombing a radio station, student dorm, and municipal library, along with the University of Algiers library.

The OAS’s attack on the University of Algiers and its library provoked widespread outrage in Algeria and around the world. It was a clear violation of the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict.

Head librarian Mahmoud Bouayad created an International Committee for the Reconstruction of the University of Algiers Library (Comité International pour la Reconstitution de la Bibliothèque Universitaire d’Alger, CIRBUA), which solicited donations of books and money from foreign governments, foundations, and organizations to help rebuild the library and its collection.

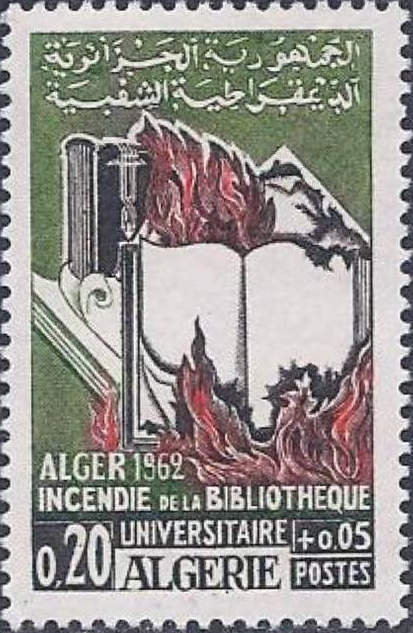

Foreign embassies and former professors together donated approximately 20,000 books to rebuild the collection. Major aid came from U.S.-based Ford Foundation and the Vatican as well as North African and Middle Eastern governments including Egypt, Jordan, Libya, and Kuwait, which issued commemorative stamps whose proceeds went to rebuilding the library.

Within Algeria, the committee called on Algerian university students and alumni to organize events like galas and sports competitions to raise awareness and money for rebuilding the library’s collections. Due to these organizing efforts, in April 1968, the University of Algiers library officially reopened.

Although it was eventually possible to rebuild the library and replenish its collection, the OAS’s arson provoked long-lasting outrage among Algerians. Today, Algeria continues to mark the June 7th anniversary of the destruction of the University of Algiers’ library as “National Book and Library Day.”

Every year, Algeria commemorates the explosion as an attempt to cripple the new Algerian nation at the moment of its independence, and as an assault on a “symbol of the Algerian people’s memory” and “on science and knowledge.”

Despite the near-universal outcry over the arson of the University of Algiers library and international support for Algeria in the aftermath, the issue of the destruction of cultural and intellectual sites in wartime is by no means resolved.

Recent United Nations reports have condemned the destruction of schools, monuments, and historical sites in the wars in Ukraine and Gaza. A UN Report from April 2024 noted that 80% of schools in Gaza have been destroyed, suggesting “it may be reasonable to ask if there is an intentional effort to comprehensively destroy the Palestinian education system.” The same report notes library and cultural heritage sites have also been destroyed, “annihilat[ing]… the cultural sector in Gaza.”

In Ukraine, a UNESCO report from February 2025 has verified the destruction of almost 500 cultural sites, including 18 libraries, since Russia’s invasion in February 2022. Such attacks against cultural sites violate international law, including the 1954 Hague Convention rules which are still in effect, as well as Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, which classifies such cultural violence as a war crime.

![]()

Learn More:

Abd-Allah, Abdi. Histoire de la Bibliothèque universitaire d’Alger et de sa reconstitution après l’incendie du 7 juin 1962. Bibliothèque universitaire d’Alger, 2022, http://bu.univ-alger.dz/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Reconstitution_de_la_B.U.pdf.

Bellisari, Andrew H. “The Evian Accords: An Uncertain Peace.” Origins: Current Events in Historical Perspective, March 2017, https://origins.osu.edu/milestones/march-2017-evian-accords-uncertain-peace.

“Commémoration du 62e anniversaire de l’incendie de la Bibliothèque universitaire d’Alger.” Algérie Presse Service. June 6, 2022, https://www.aps.dz/sante-science-technologie/171835-commemoration-du-62e-anniversaire-de-l-incendie-de-la-bibliotheque-universitaire-d-alger.

Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict with Regulations for the Execution of the Convention. § 3511. UNESCO. (1954), https://www.unesco.org/en/legal-affairs/convention-protection-cultural-property-event-armed-conflict-regulations-execution-convention.

“Incendie de la Bibliothèque universitaire d’Alger, 60 ans après.” Algérie Presse Service. June 6, 2022, https://www.aps.dz/culture/140776-incendie-de-la-bibliotheque-universitaire-d-alger-60-ans-apres.

Mallard, Thomas. “Damaged Cultural Sites in Ukraine Verified by UNESCO.” UNESCO. Updated April 16, 2025, https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/damaged-cultural-sites-ukraine-verified-unesco.

“L’Opération ‘Terre Brûlée’ se poursuit à Alger.” Le Monde. June 11, 1962, https://www.lemonde.fr/archives/article/1962/06/11/l-operation-terre-brulee-se-poursuit-a-alger_2366712_1819218.html.

Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. International Criminal Court. Updated 2021, https://www.icc-cpi.int/sites/default/files/2024-05/Rome-Statute-eng.pdf.

“UN Experts Deeply Concerned Over ‘Scholasticide’ in Gaza.” United Nations. April 18, 2024, https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2024/04/un-experts-deeply-concerned-over-scholasticide-gaza.