For many Americans, cricket is the quintessential British game. In this essay, historian Elizabeth Dillenburg shows us that cricket is global and explains how and why that happened.

In June 2024, thousands of people throughout Afghanistan took to the streets in celebration. This jubilation erupted when the Afghan cricket team advanced to the semifinals of the Men’s Cricket World Cup for the first time, winning a stunning victory over the 2021 champions, Australia, along the way.

For a country that has experienced so much conflict and turmoil in recent decades, this success in what is regarded as Afghanistan’s national sport provided a much-needed moment of collective joy.

The extraordinary achievement of the Afghan cricket team was just one underdog story that dominated the headlines of the 2024 World Cup. The United States, who were making their tournament debut, defeated the established powerhouse of Pakistan, a team that had won the World Cup in 2009 and were runners-up in 2022.

While Pakistan’s players are regarded as national heroes, members of the American team play cricket only part-time, often balancing jobs with training, and are largely unknown even to fans of the game.

2024 was not the first time that the United States hosted an international cricket competition. In fact, the first international cricket game ever played took place in New York in 1844, when the U.S. cricket team played Canada. A crowd of at least 5,000 spectators watched Canada emerge victorious from that contest.

Although cricket may be regarded as a niche sport in the United States today, it has a much longer history and was once the most popular sport in the country.

The 2024 World Cup revealed the strength and vibrancy of cricket in the 21st century. Hundreds of years after the first games of cricket were played, it is now the second most popular sport in the world, bringing together billions of fans from nations as diverse as India, South Africa, Afghanistan, and Australia.

As much as the 2024 World Cup showcased the growth and versatility of the game, it also raised questions about cricket’s future and the challenges facing the sport today, including divisions within its global governing body, the International Cricket Conference (ICC).

What lies ahead for cricket? How has this game, with its roots in the English countryside, grown into one played throughout the world today, from Caribbean beaches to Himalayan hillsides? Why did this game fade from American consciousness, and what is leading to its revitalization in the United States today? How has cricket acted as an instrument of power, resistance, and transformation?

Cricket’s long and multifaceted history provides insights into these questions. This article explores how histories of colonialism, migration, nationalism, and anticolonialism are interwoven into the fabric of cricket.

Start of Play: The Origins and Background of Cricket

The origins of cricket are shrouded in mystery and legend. The first definitive mention of cricket dates back to 1597, when records refer to boys playing a game of creckett, although it may have been played earlier under different names.

By the 1700s, there were regular mentions of the game in English records, and in 1744, members of the London Cricket Club composed the first known written rules of the game.

Multiple formats of cricket are played today.

Test matches are the oldest form of the game, with the first official match taking place in 1877. The name reflects the demanding nature of this five-day contest, which tests cricketers’ skills and endurance.

In 1971, a condensed version of the game, known as One Day International, was developed and, as the name indicates, takes place over the course of a day rather than five days. In 2005, an even shorter form of the game emerged, known as T20 or Twenty20, which lasts around three hours.

Today, 108 countries belong to the ICC. Twelve nations—Afghanistan, Australia, Bangladesh, England, India, Ireland, New Zealand, Pakistan, South Africa, Sri Lanka, West Indies, and Zimbabwe—are regarded as the powerhouses of the sport and have full membership in the ICC, meaning that they have voting rights and can play test matches.

Although these nations are diverse, they are united by a common colonial past, having all at one time been a part of the British Empire.

First Innings: Cricket as the Sport of Empire

As the British Empire expanded to various corners of the world, Britons carried the game of cricket with them. Merchants and sailors of the East India Company played the first known game of cricket in India in 1721 and later established the first cricket club outside of the British Isles, the Calcutta Cricket Club, in 1792.

Over the next century, the sport gained a foothold in other parts of the empire. The first cricket match in Australia took place in Sydney in 1803. In 1877, Australia played its first official test match against England, igniting one of the fiercest rivalries in the sport that continues down to the present day.

References to cricket games in the British West Indies date back to 1806. The first recorded cricket match in South Africa took place two years later in 1808, and by the 1880s, cricket was being played in British colonies in eastern and western Africa.

While other sports like rugby and soccer enjoyed popularity in the British colonies, cricket held a unique and privileged position as the sport of empire. Pelham Warner, who played for England between 1899 and 1912, described the importance of cricket in instilling a sense of imperial fellowship and pride:

Cricket has become more than a game. It is an institution, a passion, one might say a religion. It has got into the blood of the nation, and wherever British men and women are gathered together there will the stumps be pitched. North, South, East and West, throughout the Empire, from Lord’s to Sydney, from Hong Kong to the Spanish Main, cricket flourishes.

Cricket was seen as a way of life, and importantly, a characteristically British way of life. The British believed cricket embodied British values and served as an important educational medium that could impart British principles of loyalty, obedience, and discipline to other societies.

The sport thus became integral to the civilizing mission of imperialism and crucial in securing British hegemony abroad.

Warner described how the British viewed cricket as a marker of progress, writing that “the cricket-pavilions that have sprung up along our track may almost be called the milestones on the road of the nation’s progress.”

The British viewed cricket as a means to propagate and preserve British social norms and cultural traditions in the colonies. It also fostered a sense of an imperial community, with tours by cricket teams to other countries building relationships among disparate parts of the empire.

People in colonial societies adopted and adapted the sport, which took on diverse roles and meanings. For some, it was simply a popular pastime, providing entertainment and recreation. For others, playing cricket offered a pathway for gaining favor with colonial administrators and advancing their social and professional status. Yet for others still, excelling in this quintessential sport of empire served as a powerful way to challenge notions of British superiority.

While cricket thrived in places like India and Australia, the sport faced challenges in other parts of the empire. Competition from established sporting cultures, resistance from colonial administrators to promoting the game, climate, geography, and social structures within the colonies hindered the growth of cricket in some regions, including Canada and parts of Africa.

Cricket: A Lost American Pastime?

While cricket was expanding globally during the 1800s, its popularity was waning in the United States.

Like cricket in other parts of the world, British colonists brought the game to America. Among its fans were Founding Fathers, including Benjamin Franklin and George Washington, and presidents, including Abraham Lincoln.

Independence from Britain did not diminish Americans’ love of cricket. Instead, its decline coincided with the Civil War, as Americans increasingly turned to baseball.

Yet cricket did not immediately disappear from American sporting life after the Civil War. It still had a following, particularly in Philadelphia and New York, and teams from England, Australia, and the West Indies toured the United States in the latter half of the 19th century. However, the exclusion of the United States from the Imperial Cricket Conference ultimately cemented cricket’s decline in America.

Founded in 1909, the Imperial Cricket Conference operated as the sport’s governing body and was the predecessor of the current International Cricket Council. The Conference formally tied cricket to the empire, and its structure reproduced broader colonial power relations, with England assuming leadership of the Conference.

The Imperial Cricket Conference might have strengthened the bonds of empire and facilitated the growth of the sport within the empire, but by forming this organization along imperial lines, it notably excluded the United States and further marginalized the sport in America.

Following On: Cricket’s Transformation in the Postcolonial Era

Cricket was not only a tool of colonial power but also an instrument of colonial resistance. As nations declared their independence from Britain following the Second World War, people in former British colonies reinvented and reappropriated the game.

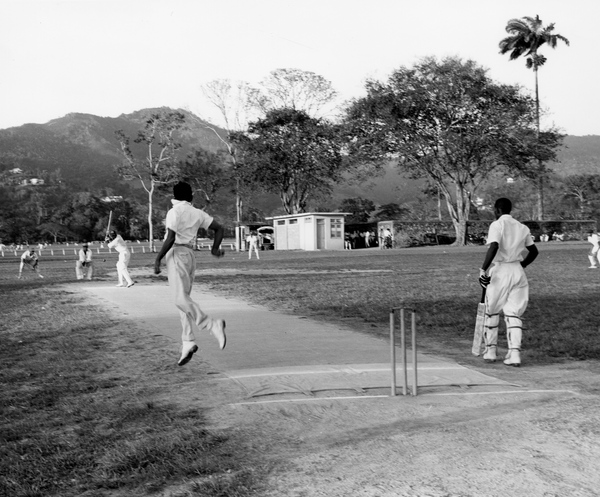

In regions like the West Indies, South Africa, India, and Pakistan, cricket pitches served as powerful and symbolic arenas of liberation, protest, identity formation, and national contestation.

Cricket also reflected broader geopolitical changes.

In recent decades, the locus of power in the sport shifted from England to South Asia, which provided new fan bases and reinvigorated this centuries-old game to meet the changing demands of the 21st century.

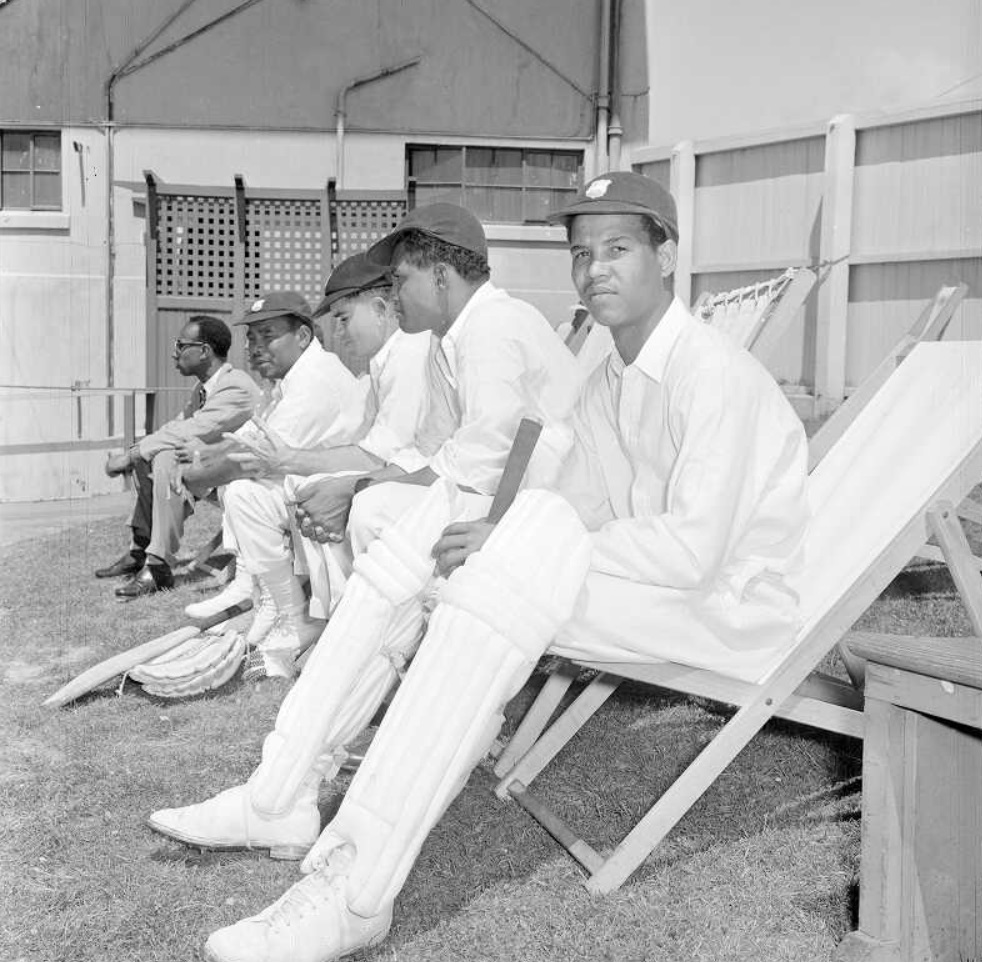

Cricket as an Instrument of Empowerment in the West Indies

The golden age of West Indian cricket came in the 1960s and 1970s as the islands gained independence from colonial rule. The rise of the West Indian cricket team and the region’s liberation from colonialism were not coincidental but instead deeply intertwined.

As historian C.L.R. James observed in his book, Beyond a Boundary, “West Indians crowding to Tests bring with them the whole past history and future hopes of the islands.”

James recognized the potential of cricket for Black empowerment and solidarity. Through the sport, West Indians could resist the dehumanizing effects of colonial rule and racism and assert their equality, identity, and self-determination.

Cricket as a Catalyst for Protest against Apartheid

The political nature of cricket became undeniable during the apartheid era in South Africa. Under apartheid, South Africa banned racial mixing in sports and barred Black, Coloured (multiracial), and Asian people from participating in formal or professional sporting activities. The government also prohibited racially mixed teams from competing abroad and required visiting international teams to be composed of only white players.

These policies divided the cricketing world.

Although Britain and Australia continued to play matches with South Africa, other teams—including India, Pakistan, and the West Indies—condemned South Africa’s racial policies and refused to play matches there.

They also criticized Britain’s continued association with the apartheid government, threatening to withdraw from tours to England in protest. These tensions surrounding apartheid reached a climax with the Basil D’Oliveira Affair.

Born in South Africa in 1931, Basil D’Oliveira’s Portuguese Indian ancestry meant that he was considered Coloured, according to South Africa’s racial classification system, and was prohibited from playing for the South African national team. D’Oliveira nevertheless established a successful cricketing career, first in South Africa and later in England.

In 1968, as England prepared to play matches in South Africa, the South African government declared that it would deny entry to England’s team if it included D’Oliveira. Controversy and protests erupted when England announced that its team to South Africa would not include D’Oliveira.

When England later brought D’Oliveira into the team to replace an injured player, South African Prime Minister B. J. Vorster (1915-1983) condemned the move as capitulating to the anti-apartheid movement and reaffirmed his refusal to allow a team that included D’Oliveira into South Africa. Faced with mounting public pressure within Britain and internationally, England chose to cancel the tour.

The D’Oliveira Affair ignited a broader sports boycott of South Africa.

For the next two decades, South Africa remained isolated from formal international cricket. Official tours by international teams would only return until 1991 as apartheid came to an end.

The D’Oliveira Affair brought to the fore issues of race in the cricketing world and weakened the apartheid regime. The plight of D’Oliveira exposed the injustices of apartheid to a broader audience and revealed how cricket could act as a platform to challenge racism and injustice.

Cricket as a Tool of Diplomacy in India and Pakistan

Like in South Africa and the West Indies, cricket matches between India and Pakistan highlight the profoundly political nature of sport and its connection to national identity.

Although first played on the Indian subcontinent more than 300 years ago, cricket grew exponentially in popularity and importance in the post-independence era. In these highly diverse nations, cricket acts as a unifying force that transcends different languages, religions, castes, classes, and regions.

Following the violent partition of India and Pakistan in 1947, political tensions and feelings of anger and distrust between the two countries fueled one of sport’s fiercest rivalries. The cricket pitch provided a type of battlefield where the neighbors challenged each other.

Especially in the decades following the partition, cricket matches between India and Pakistan ignited intense nationalist fervor and competitiveness, epitomizing George Orwell’s famous description of sport as “war minus the shooting.”

While cricket can fuel resentment and hostilities, matches have also provided opportunities to bring Pakistanis and Indians together, and politicians have appreciated the potential of “cricket diplomacy” to improve relations.

Most notably, Pakistan’s President Mohammad Zia-ul-Haq (1924-1988) pursued a mission of “Cricket for Peace” in 1987, visiting India to watch a match between the two countries during a period of escalating tensions over Kashmir. His appearance led to informal talks between the two nations that improved relations and resulted in the withdrawal of troops in Kashmir.

While cricket’s impact on easing the strained relations between the countries has been more limited recently, there is still hope that the game can bridge divisions and foster greater dialogue and goodwill between India and Pakistan.

Cricket as a National Symbol in Afghanistan

The popularity of cricket in Pakistan sparked interest in the sport in neighboring Afghanistan. As in other cricketing nations across the world, the British originally brought the sport to Afghanistan, where the first games of cricket were played in the late 1830s.

However, the sport did not gain popularity there until the 1990s. This rebirth of cricket originated in refugee camps in Pakistan, which were home to millions of Afghans who fled their country between 1979 and 2001 due to the Soviet-Afghan War (1979-1989), Afghan Civil War (1992-1996), and the Taliban.

In these camps, cricket became a popular form of entertainment. Recognizing cricket’s popularity and potential to strengthen Islamic identity and unify Afghans, the Taliban lifted its ban on cricket in 2000, making it the only sport approved in Afghanistan.

The fall of the Taliban in 2001 and the return of refugees to Afghanistan led to the expansion of cricket there. Since then, the Afghan national team has risen rapidly in the ranks of world cricket, becoming a full member of the ICC in 2017. This enormous success has made cricket a powerful symbol of Afghanistan’s resilience.

While the prospect of Afghan men’s cricket looks bright, evidenced by their achievements in the 2024 World Cup, the future for women players is less optimistic. Following the fall of the Taliban in 2001, the Afghan government increased opportunities for women to play cricket, and a women’s team was formed in 2010.

When the Taliban returned to power in 2021, it championed the men’s team and expressed its desire for Afghanistan to become a global cricketing power but simultaneously banned women’s sports and raided the homes of women athletes. Women players burned their cricket equipment and were forced to flee their homes, most settling in Australia.

Following the success of the men’s team in the 2024 World Cup, the Afghan women players in Australia wrote to the ICC, expressing their sorrow at not being able to represent their country and requesting that they be recognized as the official women’s team of Afghanistan, but they received no response or support from the ICC.

Like debates around apartheid and race in the 1960s, the question of whether to continue to support cricket in Afghanistan despite its deplorable treatment of women has divided the international cricket community.

Although the ICC requires its full members to have a national women’s team, the majority of ICC members oppose penalizing Afghanistan for its banning of women’s cricket. However, Australia has declined to play series against Afghanistan to protest women’s exclusion from sport.

In recent years, the ICC has affirmed that supporting women’s cricket is a key priority, but the situation in Afghanistan may test the limits of its professed commitment to women’s cricket and gender equality.

Sticky Wicket: The Future of Cricket

Much like Afghanistan’s success in the 2024 World Cup, the inspiring story of the United States’s victory against Pakistan is more complicated than it first appears and raises questions about the future of the sport.

Over 100 years after U.S. exclusion from the Imperial Cricket Conference seemed to signal the death knell of cricket in America, the sport is experiencing a revival, propelled by Caribbean and South Asian communities there.

The question, however, is whether the sport can gain a greater following that extends beyond these communities. The vast, lucrative market of the United States has made the growth of American cricket a tantalizing prospect for cricket enthusiasts and investors, but can cricket establish a place in American sporting culture alongside football, basketball, baseball, hockey, soccer, and golf?

The surprising victory against Pakistan made headlines across the cricketing world—but barely made a ripple in the United States. Organizers hoped that the United States’s hosting of the World Cup would serve as a catalyst to cricket’s growth in the country, much like the soccer World Cup of 1994 had sparked a new enthusiasm for soccer, but at least in the short term, cricket does not seem to have captured Americans’ imagination in the same way.

A further test of cricket’s future potential will come in 2028, when it will be one of the sports in the Summer Olympics in Los Angeles. Like the 2024 World Cup, it is hoped that its inclusion in the Olympics will expose cricket to new audiences.

Whether cricket can continue expand its global reach in areas like North America, the Middle East, and East Asia and develop a larger, sustained fan base in countries like the United States remains to be seen, but cricket’s survival and enduring popularity today is a testament to the game’s adaptability.

Cricket’s transformation from a game played in the English countryside into a sport played throughout the world and embraced by billions of people serves as a valuable lens for understanding the histories of colonialism and decolonization. For centuries, the British used cricket to reinforce their colonial hegemony across various parts of the world.

Yet the cricket pitch also served as a battleground for challenging these structures of colonial power, evidenced by protests surrounding cricket in apartheid South Africa, and a stage where national identities were forged and strengthened, as the rise of West Indian cricket demonstrates.

The history of cricket is also a story of migration, highlighted by the current Afghan and American teams. Cricket’s dynamic nature has made it a vehicle for diverse political agendas, apparent in the practice of “cricket diplomacy” between India and Pakistan and the Taliban’s use of the sport to unify Afghans and legitimize its rule.

More than a mere pastime, cricket provides insights into global society, politics, and economics and reveals how sport can both bolster and disrupt structures of power.

C.L.R. James, Beyond a Boundary. Yellow Jersey Press, 2005.

George Orwell. “The Sporting Spirit.” Tribune, December 14, 1945, from The Orwell

Foundation, https://www.orwellfoundation.com/the-orwell-foundation/orwell/essays-and-other-works/the-sporting-spirit/, accessed April 3, 2025.

P. F. Warner. England v. Australia: the record of a memorable tour. Mills & Boon, 1912.

Pelham Warner. Cricket in Many Climes. William Heinemann, 1900.