On August 6, 1962, the island of Jamaica became an independent nation, making it the first sovereign English-speaking country in the Caribbean. The tremendous victory of this likkle but tallawah island (“small but mighty” in Jamaican) was one triumph in the long history of Black sovereignty and nationalism that led to the disintegration of the British empire in the Caribbean.

Jamaica had been a Spanish colony until 1655 when Britain launched the Western Design, an expedition across the Spanish Caribbean during the Anglo-Spanish War. Although English general Oliver Cromwell’s invasion of Jamaica in May 1655 ended rather unsuccessfully and his plan for the Western Design overwhelmingly failed, Jamaica was formally ceded to Britain in the 1670 Treaty of Madrid.

Jamaica remained a British colony for almost three hundred years through the Maroon Wars (1728-1739/40 and 1795-1796), Tacky’s Rebellion (a defining revolt in the British Caribbean in 1760), and Britain’s abolition of the slave trade in 1807 and of slavery as an institution in 1834.

For the island formerly dependent on slave labor and sugar production, the deconstruction of the plantation system further exacerbated economic suffering after emancipation. It also sowed widespread dissatisfaction among the Black majority as racial discrimination persisted.

Led by now national hero Paul Bogle, the Black majority erupted in protest on October 11, 1865, in Morant Bay. The planter class’s white militia eventually suppressed the Morant Bay Rebellion, arresting and executing hundreds of Black Jamaicans, including Bogle, to maintain colonial reign and racial inequality.

Centuries of civil unrest and activism in Jamaica and the rest of the Caribbean intensified in the 1900s.

Notably, Jamaican-born Pan-Africanist Marcus Garvey appealed for improved living conditions for Black Jamaicans and later gained international acclaim when he and first wife, Amy Ashwood Garvey, founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) and African Communities League in Kingston in 1914.

Though Garvey was not elected to public office in Jamaica, the UNIA was responsible for many Black Jamaicans’ anticolonial and nationalist sentiments during the early twentieth century.

Social inequalities worsened during the era of the World Wars, and the Great Depression increased labor unrest across the British West Indies in the 1930s. Workplace strikes and riots took place in Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, British Honduras (present-day Belize), and British Guiana (present-day Guyana), among others.

Agricultural workers, dockworkers, and miners were amongst the largest groups who protested the economic conditions brought on by reduced wages, insufficient social welfare, and the increased cost of living.

Working-class consciousness also increased at this time due to union organizing and the spread of ideas from travel, spurring another period of increased nationalist sentiment.

In Jamaica, labor leader Alexander Bustamante founded the Bustamante Industrial Trade Union and one of Jamaica’s two political parties, the Jamaica Labour Party (JLP), in 1938 and 1943 respectively. Bustamante’s leadership was particularly popular amongst the Black working class.

In the decades that followed, the JLP and its opposition, the People’s National Party, both enacted a series of constitutional amendments as they moved toward independence, establishing universal adult suffrage and a cabinet of ministers under the direction of a premier, and later a prime minister.

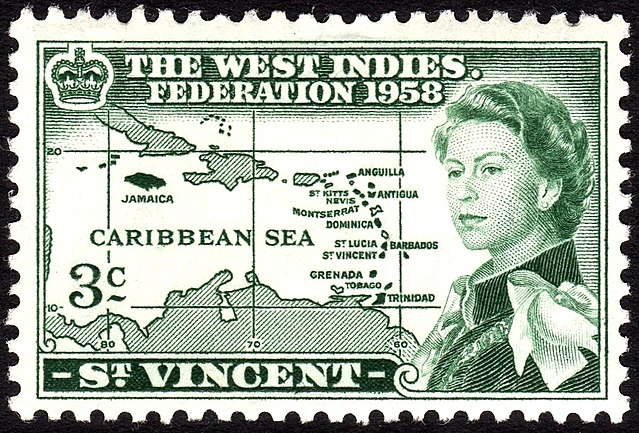

The initial plan for political independence in the British West Indies took the form of the West Indian Federation, a political union of islands in the Greater and Lesser Antilles in a single independent state. From 1958 to 1962, Jamaica was one of ten British colonies unified into the Federation from the British Caribbean Federation Act of 1956. The Federation still maintained Queen Elizabeth II as its head of state and appointed Bajan politician and premier Sir Grantley Adams as prime minister.

Trinidad and Tobago, and the “Little Eight” under the leadership of Queen Elizabeth II.

Despite uniting in the hope of independence, the West Indian Federation faced several political challenges including disagreements on the location of its capital, political leadership, and competing views on individual nationalism. The Federation eventually dissolved by 1961 as Jamaican politicians grew dissatisfied with the union’s enduring colonial status.

On September 19 of that year, Jamaica issued a referendum on their continued participation in the West Indian Federation, with 54.1% of the population voting against. Jamaica resigned from the Federation, and Trinidad and Tobago followed suit shortly thereafter, with then Trinidadian Premier Eric Williams stating that “one from ten leaves nought.”

Jamaica’s decision to leave the union and immediately seek independence demonstrates its influence on the Federation, leaving the “Little Eight,” the smallest of the ten states, to negotiate maintaining the union for few more months. Several of the Little Eight then went on to seek independence from the United Kingdom over the next two decades.

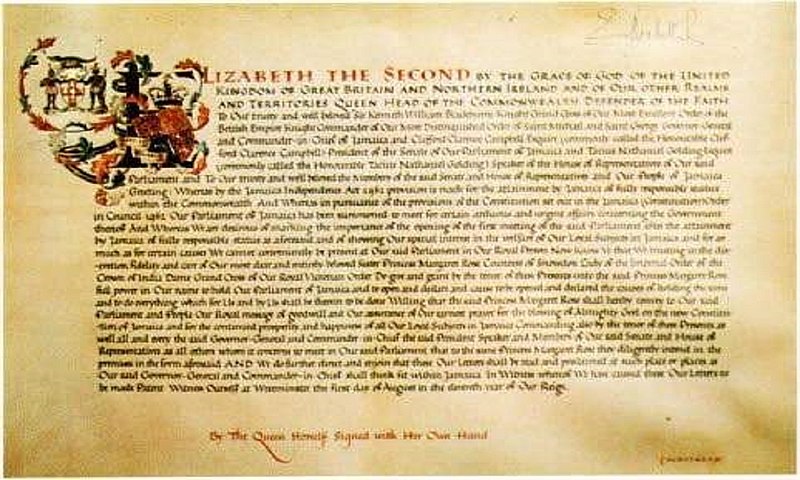

The Jamaica Independence Act was formerly presented on May 22, 1962, was later approved by Royal assent on July 19, and came into effect on August 6.

Today, Jamaica’s independence day, as well as Trinidad and Tobago’s on August 31st, mark a necessary transition for the Atlantic world. Indebted as well to Haiti, the world’s first free Black republic in the Western Hemisphere, which declared independence from France in 1804, Jamaica’s nationalist journey reflects a longer history in the partial collapse of Britain’s foothold of Caribbean colonialism (partial because Britain still holds several overseas territories including Anguilla, Bermuda, the British Virgin Islands, and Turks and Caicos).

Despite gaining independence between the 1960s and 1980s, most of the former Federation transitioned to being parliamentary constitutional monarchies with British influence under the hereditary monarchy of Queen Elizabeth II.

However, a shift away from a connection to the United Kingdom and the monarchy has begun. Just last year, Barbados moved from being a constitutional monarchy to a parliamentary republic on its 55th independence day. Though many nations, including Jamaica, have made several attempts at attaining republic status, Barbados’s success is a significant progression towards Black nationalism and sovereignty in the twenty-first century.

Celebrating the sixtieth anniversary of independence under the theme, “Reigniting a Nation for Greatness,” Jamaica has shared this goal of full sovereignty and announced that the nation plans to become a republic by the 2025 election.

Over two centuries since the abolition of slavery, Black activism has shaped Jamaica, a nation heavily regarded for Black empowerment and domination in international music, sports, and culture. Jamaica’s independence signifies a new milestone of Black Atlantic self-determination. It will hopefully drive other islands in the Caribbean towards independence and autonomy into the twenty-first century and beyond.

![]()

Learn More:

Brown, Vincent. Tacky's Revolt: The Story of an Atlantic Slave War. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2022.

Ford-Smith, Honor. “Unruly Virtues of the Spectacular: Performing Engendered Nationalisms in the UNIA in Jamaica.” Interventions 6, no. 1 (2004): 18–44. doi:10.1080/1369801042000185642

Hart, Richard. The End of Empire: Transition to Independence in Jamaica and Other Caribbean Region Colonies. Kingston, Jamaica: Arawak, 2006.

Meeks, Brian. “The Legacies of Independence in Jamaica: Towards a Half Century

Assessment”, Journal of the University College of the Cayman Islands, Vol.5 (August 2011), 26-36.

Miller, Alexandria, host. “The West Indian Federation (1958-1962) with Dr. Patsy Lewis.” Strictly Facts: A Guide to Caribbean History & Culture (podcast). August 4, 2021.

Nettleford, Rex. Jamaica in Independence: Essays on the Early Years. Kingston, Jamaica: Heinemann Caribbean, 1989.

Palmer, Colin A. Inward Yearnings: Jamaica's Journey to Nationhood. Kingston, Jamaica: The University of the West Indies Press, 2016.

Timm, Birte. Nationalists Abroad: The Jamaica Progressive League and the Foundations of Jamaican Independence. Kingston: Jamaica: Ian Randle Publishers, 2016.