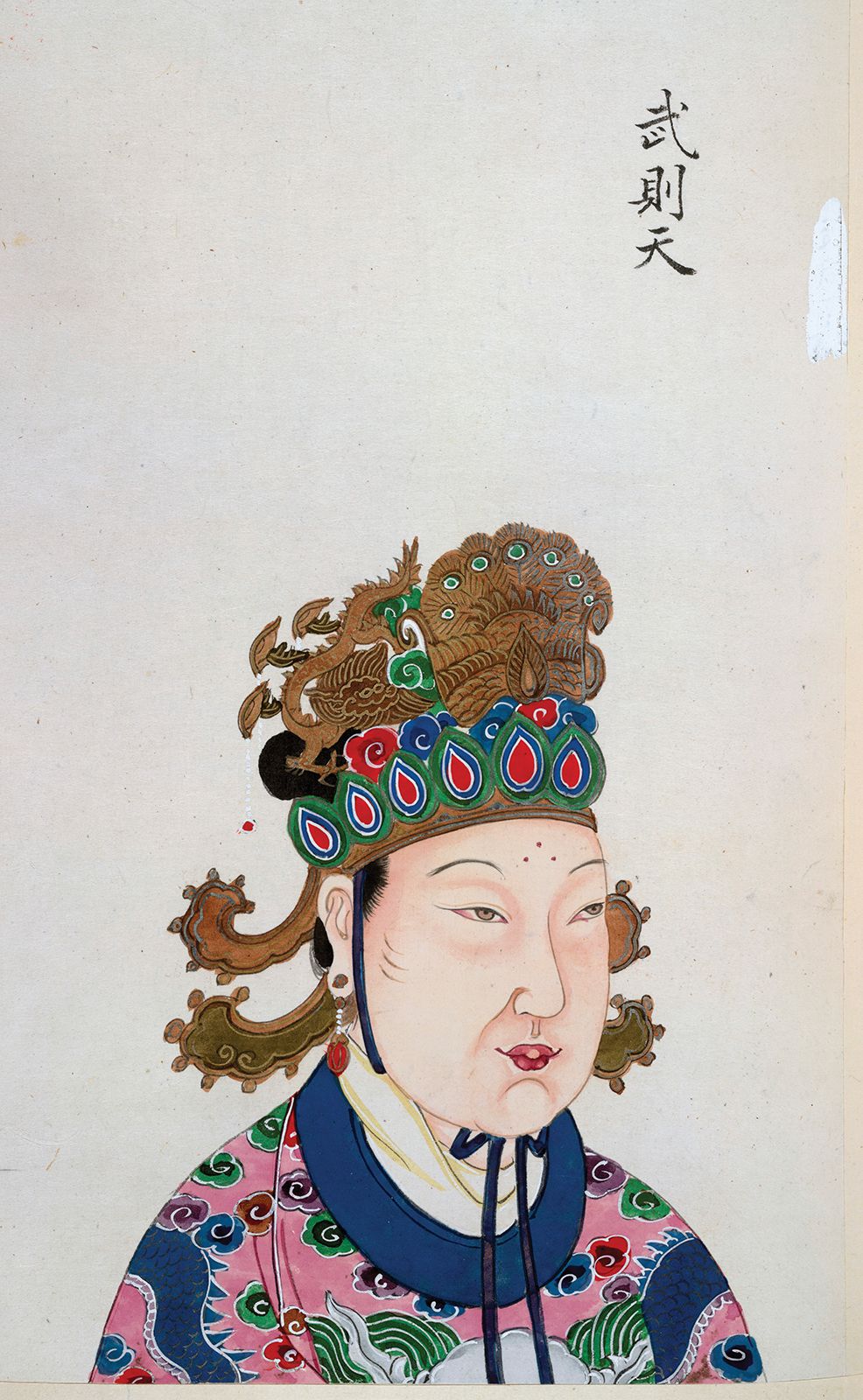

Wu Zetian’s life (624–705 CE; r. 690–705) is a study in ambition, resilience, and the ability to bend an entire society’s rules to her will. Her current appellation, Zetian, was her posthumous title. Her official given name was Zhao, a character she created for herself, meaning “the sun, moon, and the sky.”

Her father, Wu Shiyue, was a prominent supporter of the rebellion that toppled the Sui and established the Tang dynasty. He rose to become Minister of Works, giving Wu Zetian an early taste of both power and the fragility of fortune.

Not long after her birth, at her father’s request, Yuan Tiangang—the foremost diviner of his day—studied her. Struck by her features, Yuan declared that the child would one day rule the realm.

As a child, she lived with her father, her birth mother (a concubine), and her father’s principal wife, along with two older half-brothers, two full sisters, and a tangle of cousins—all competing for attention and status. After her father’s death, the family’s fortunes declined. Likely bullied by her brothers and cousins, Wu Zetian grew determined to escape her fate.

When a eunuch arrived looking for candidates to serve as imperial concubines, Wu, at thirteen, jumped at the chance and entered the court of Emperor Taizong. But her days at court were unremarkable; Taizong, still mourning his late empress, paid little mind to the new arrivals.

Everything changed in 649. As Taizong grew gravely ill, his concubines and Crown Prince Li Zhi tended to him. Wu Zetian and the prince got involved in a taboo liaison. When Taizong died, Wu Zetian, 25, was sent to a convent, while Li Zhi (later known as Gaozong) ascended the throne.

Wu Zetian was so devastated by her loss of status that she wrote a poem about it, rolling her words and a treasured pomegranate-patterned dress into a bundle and had it smuggled into the palace. The poem moved Li Zhi to the core, but he felt powerless to help her.

Salvation then came from an unexpected quarter: Empress Wang. Barren and threatened by the emperor’s favorite, Consort Xiao, Wang hoped to use Wu as an ally in her own struggles for power. With Empress Wang’s intervention, Wu returned to court in flagrant violation of convention.

Once inside the palace, Wu Zetian soon maneuvered her way to the top, first aligning with Empress Wang against Consort Xiao, then turning on both. She orchestrated their removal and imprisonment, ultimately having them mutilated and left to die in vats of wine. With her rivals gone, Wu Zetian ascended to the throne of empress.

Her rise was ruthless and her reign, once she gained real power, even more so. She allied herself with immoral ministers such as Xu Jingzong and dispatched the Old Guard, powerful officials from the previous reign. When court protocol barred females from holding court, she instituted the practice of ruling from behind a bamboo curtain.

After Emperor Gaozong’s death in 684, Wu Zetian began to call the shots at court until 690, when she took the unprecedented step of proclaiming herself emperor, toppling the Tang and establishing her own Zhou dynasty. For the next fifteen years, she was the undisputed sovereign of China—the only woman to ever rule the entire country in her own right.

Blending terror with reform, Wu Zetian’s reign was a mixed bag. She employed “Legalist” law officers, such as Zhou Xing and Lai Junchen, known for their cruelty and zeal, to destroy her challengers. Her campaign of purges left countless dead or exiled, including her own brothers and sons.

And yet, Wu Zetian also sought to elevate women’s roles. She decreed that mourning periods for mothers should match those for fathers, placing wives and husbands on equal footing in death. She reformed ancestral worship, requiring that female ancestors be honored alongside their male counterparts. She appointed talented women like Shangguan Wan’er—whose family she had all but destroyed—to high positions, using her as a chief drafter of imperial edicts.

Wu Zetian’s personal life was as unconventional as her politics. She abolished the Rear Palace, the traditional harem, but kept her troop of male companions. Four of them were well-known: monk Xue Huaiyi, Zhang Changzong, Zhang Yizhi, and Shen Nanqiu. All but the last one met violent ends.

Of her four sons, the eldest, Li Hong—popular but frail—died suddenly under mysterious circumstances. The second, Li Xian, known for his benevolence and filial piety, was exiled on dubious charges and later killed by imperial agents. Her two remaining sons ascended the throne as puppet emperors after her husband Gaozong’s death, but she eventually deposed them both and claimed the throne for herself.

Wu Zetian’s reign came to an end in 705 when a palace coup toppled her rule. She died soon after at the age of eighty-one.

Her legacy is unique: among the most powerful women in world history—Hatshepsut in Egypt, Cleopatra in Rome, Theodora and Irene in Byzantium, Maria Theresa in Austria, and Catherine the Great in Russia—Wu Zetian alone overthrew a strong dynasty and ruled as emperor in her own right.

She shattered gender roles, reimagined rituals, and inspired generations of latecomers (including Empress Dowager Cixi and Madame Mao Jiang Qing), though none could match her iron will and cunning.

Wu Zetian stands as proof that even in the most male-dominated societies, a woman could rise to the very summit of power, and shape history on her own terms.

![]()

Learn More:

Guisso, Richard W. L. 1978. Wu Tse-T’ien and the Politics of Legitimation in T’ang China. Bellingham, Wash.: Center for East Asian Studies, Western Washington University.

Rothschild, N. Harry. 2007. Wu Zhao: China’s Only Female Emperor. New York: Pearson Longman.

Rothschild, N. Harry. 2017. Emperor Wu Zhao and Her Pantheon of Devis, Divinities, and Dynastic Mothers. New York: Columbia University Press.

Twitchett, Denis C., ed. 1979. The Cambridge History of China, volume 3: Sui and T’ang China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Twitchett, Denis C. 1992. The Writing of Official History under the T’ang. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992

Xiong, Victor Cunrui. 20243. Heavenly Empress (Tianhou): The Age of Wu Zetian. Taipei: Ainosco Press, 2023.