Although it is generally accepted that World War II began with Hitler’s invasion of Poland in 1939, the roots of that global conflict actually reach back to the Marco Polo Bridge Incident of July 7, 1937. A clash between troops from the Republic of China (ROC) and the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) may have had little immediate importance for Americans and Europeans but it mattered a great deal to those living throughout East and Southeast Asia. They soon found themselves at the center of a violent conflict to shape and reshape the world order.

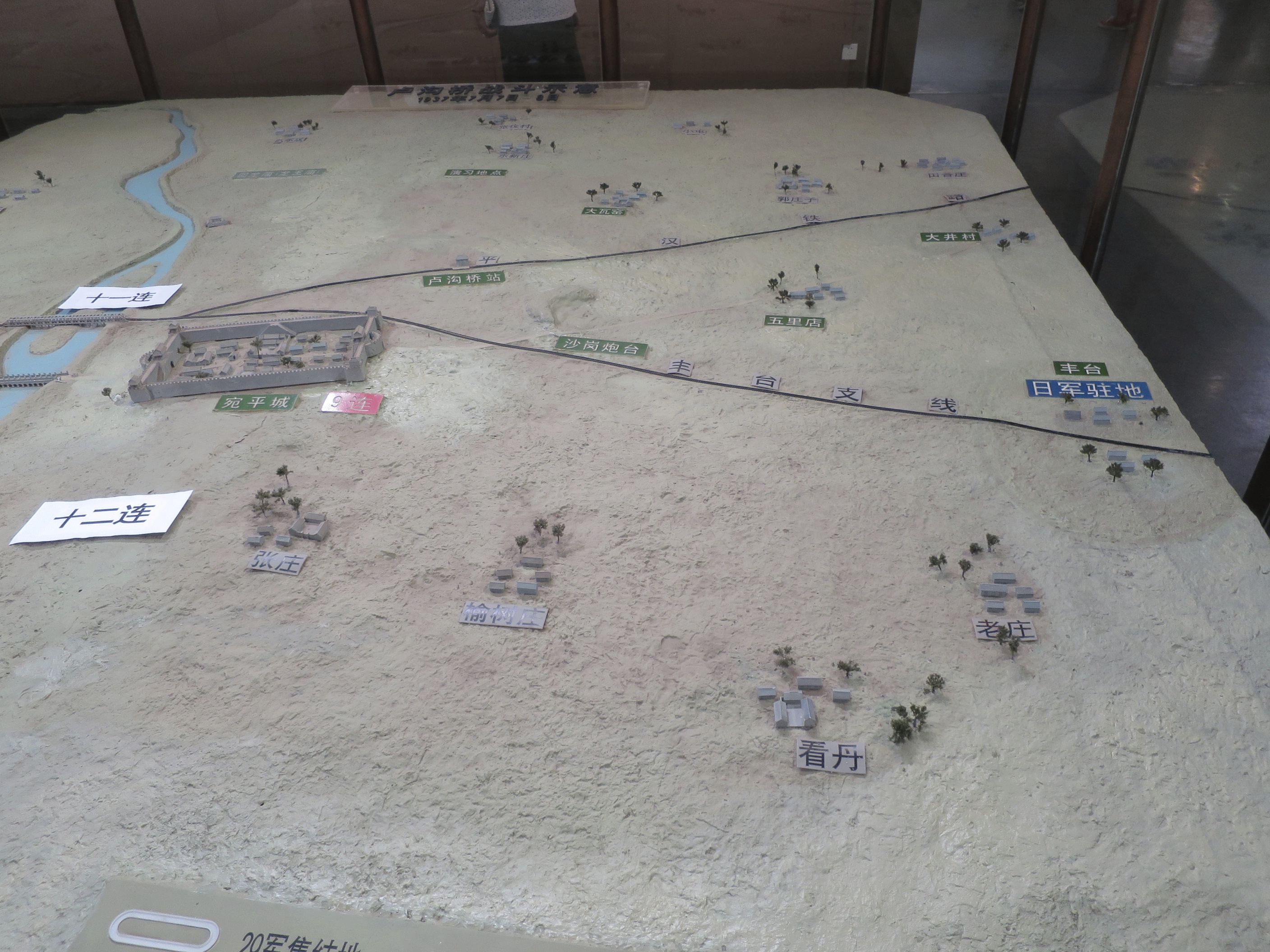

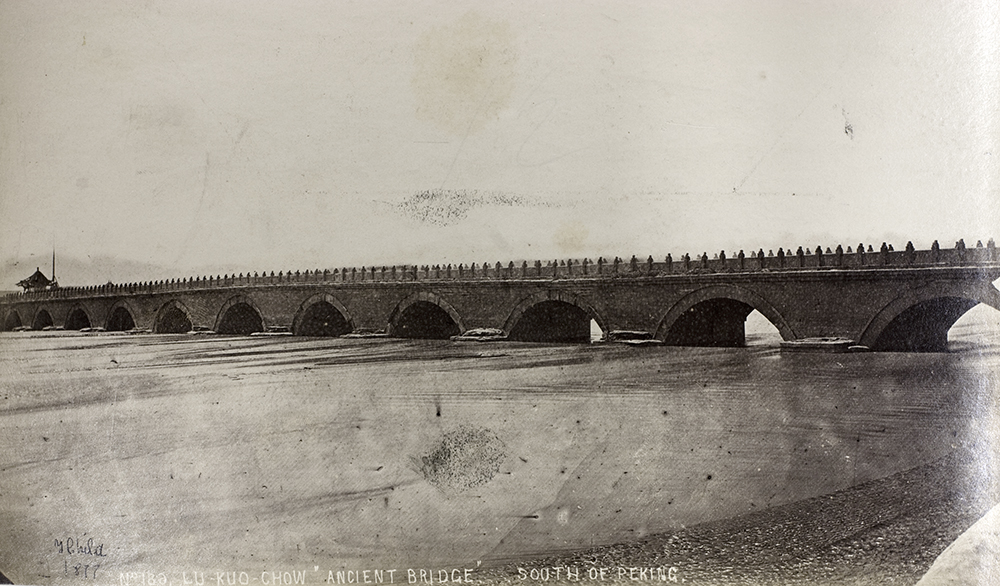

The Marco Polo Bridge Incident transpired a mere dozen or so miles southwest of Beijing’s Forbidden City in the vicinity of the walled municipality of Wanping. The eponymous 11-arched stone bridge, dating from the 1180s and mentioned by Marco Polo (hence the name in English), leads into Wanping’s Western Gate. In 1937, IJA night maneuvers directed from nearby Fengtai town quickly snowballed into an assault on Wanping and the bridge, prompting a Chinese response.

Like the bridge, with its balustrade topped by innumerable ornamental carved-stone lions, early twentieth-century East Asian history itself is segmented by events termed “incidents” when they occurred in efforts to minimize their importance. None turned out to be as momentous as the Marco Polo Bridge one. Despite its significance, however, the instigators, the defenders, the event, and the setting are still, to some extent, shrouded in obscurity.

What we can say with certitude is that, after July 7, 1937, Japan and China would be in continuous war until 1945 and little in East Asia, Southeast Asia, or the Pacific would remain the same.

By the end of the war, Japan would lose most of its post-1868 empire, including Korea and Taiwan. The Chinese Communist Party would be reborn and re-legitimized through its wartime mobilization and alliance with China’s then-ruling party, the Nationalists (KMT/GMD). And, after a strong start against the IJA, the KMT itself would be weakened irreparably by the war.

Russia and America would replace Japan, Britain, and France as the leading imperial powers in Asia. Southeast Asia, if not actually liberated from colonialism by war’s end in September 1945, was working on it. And, more generally, what was then termed “the prestige of the White race” in Asia would vanish forever.

Already in Fall 1937, journalists began filling in the context and implications of the Marco Polo Bridge Incident for their readers. The Pacific affairs journalist Upton Close argued provocatively that circumstantial evidence from each country suggested that both may have known the actual date on which the war would begin and had long been preparing for it.

Although Close’s view is not widely accepted today, he observed that all of Shanghai’s Chinese-owned bullion had been moved to Hong Kong in the six weeks prior to July 7. Further, in Washington, the ROC began organizing sales of bullion on the very day of the Incident. And the Chinese government, Close claimed, had prepared for a two-year war of resistance—six years too short as it turned out.

“The Japanese, too, knew the date—likely before the Chinese discovered it,” contended Close. Cotton import statistics from America and India before July 1937 indicated Japan had accumulated enough bales for three months, not its usual two months, of manufacturing. Similarly, pig and scrap iron imports also suggested that Japan was ready for a three-month campaign to allow the IJA to consolidate North China as a second Manchukuo.

Like the Chinese, though, the Japanese gravely underestimated the war’s timetable. When asked, Japan’s war minister first told Hirohito that the war would last a month but later temporized at three months. The Japanese would have been better off consulting Close, who predicted accurately that Japan’s military, already operating independently of Tokyo on the Asian mainland, would soon bog itself down in the vastness of China.

The seemingly local conflict expanded astonishingly rapidly into a protracted eight-year continental war. First, though, Japan capitalized on the Marco Polo Bridge Incident to seize the nearby railway line, key to occupying Beijing and Tianjin by the end of July. In August, fighting moved to the Shanghai area and, by the end of the year, the ROC capital of Nanjing fell in what one military commentator called “the worst holocaust of brutality since the troops of Count [Johann] Tilly sacked Magdeburg in the Thirty Years’ War.”

To minimize the risk of Western involvement, the Japanese skipped any formal declaration of war until late 1941, instead giving the aftermath of the Wanping/Marco Polo Bridge-area conflict the formal name by which they still call it, “The China Incident.”

As time passed, Japan’s broad goals of establishing an anti-Communist East Asian order, a reorganized Chinese economy, and a stable new Chinese government friendly to Japan became ever-more elusive.

In their desperation to end the war by imposing a full embargo on Chiang Kai-shek’s wartime government, from late 1941, the Japanese attacked and invaded British-owned Hong Kong, the U.S.-controlled Philippines, Southeast Asia from French Indochina across Thailand to British Malaya, Singapore, and Burma; the Dutch East Indies; and Australia-administered New Guinea. They even bombed Darwin in northern Australia. And, of course, they attacked the American-controlled, pre-statehood territory of Hawaii.

In the process, the Japanese added to the China Incident what they call the Pacific War (1941-45) and what the West calls World War II. Behind it all, what English-speakers now call the 2nd Sino-Japanese War (1937-45), begun in suburban Beijing, churned on unceasingly and remained the justification for all of Japan’s numerous “sideshows.” Only China, alone among the attacked colonial and independent Asian nations, resisted the Japanese steadfastly until 1945.

![]()

Learn More:

Close, Upton. “Both Japan, China knew when war would start,” Oakland (CA) Tribune, 19 Sep 1937, 5 (accessed via Newspapers.com 08 June 2022).

Dorn, Frank. The Sino-Japanese War, 1937-41; From Marco Polo Bridge to Pearl Harbor. NY: MacMillan, 1974.

Drea, Edward J. Japan’s Imperial Army; Its Rise & Fall, 1853-1945. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2009.

Ienaga, Saburo. The Pacific War: World War II and the Japanese, 1931-1945; A Critical Perspective on Japan’s Role in World War II. Transl. by Frank Baldwin. NY: Pantheon, 1978.

MacKinnon, Stephen, and Diana Lary, Ezra Vogel, eds. China at War: Regions of China, 1937-1945. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007.

Mitter, Rana. Forgotten Ally, China’s World War II, 1937-1945. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2013.

Morley, James William, ed. The China Quagmire, Japan’s Expansion on the Asian Continent 1933-1941. NY: Columbia University Press, 1983.

Peattie, Mark, and Edward Drea, Hans van de Ven, eds. The Battle for China: Essays on the Military History of the Sino-Japanese War, 1937-1945. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2011.