Is it acceptable to wear a beard? What does a man’s shave tell the world about his character? Christopher Oldstone-Moore’s new book Of Beards and Men: The Revealing History of Facial Hair argues that the decision to grow or cut facial hair is much more than a fashion statement.

In this book beards provide a window for examining the ways in which cultures have defined and controlled images of masculinity. This lens has led Oldstone-Moore to posit four “principles of beard history” which are: facial hair tracks manliness across cultures; facial hair has a political dimension; it is based on a dichotomy of shaved and unshaved; and finally that the gradual nature of these changes requires the long view of history. Through an extensive examination of primary sources which range from Neo-Assyrian sculpture to twenty first century advertising, Oldstone-Moore identifies four distinct “beard movements” over the course of the history of Western civilization.

|

| King Ashurnasirpal II wore the beard of a warrior king, intricately braided and asserting his dominance over his clean shaven subjects. |

Using a chronological structure, Oldstone-Moore begins his work by looking at biology and anthropology to discuss the biological origins and uses of the beard. A selective review of the most current evolutionary theories reveals that beards are connected either to ornamentation or aggression, that is their origins lie in wooing mates or intimidating foes.

These theories of ancient beards are supplemented by the results of modern man’s marketing, in which college age students have been surveyed across the twentieth century about the attraction or menace of burly men. Acknowledging both the scarcity of evidence and the fickleness of college students’ opinions, Oldstone-Moore wisely resigns the origins of the beard to the unknown.

From here he engages more directly with the historical evidence, drawing clear dichotomies of facial hair in social hierarchies in ancient Mesopotamian history. The bearded warrior kings and completely shaven priestly classes established a clear distinction between the burly natural man and the submissively shaven supernatural. This dichotomy between fighting facial hair and priestly pruning continued into antiquity with Alexander’s revolutionary shaven army and Hadrian’s philosophical beard. The ecclesiology of Jesus’ beard and the beards of the holy created a recurring problem in the Middle Ages, as Roman Catholic Church officials attempted to regulate facial hair. Crusading kings and pious priests all took up the razor in deference to Jesus’ divine beard.

|

|

| The carefully shaven face of Pope Gregory X was a symbol of his holy authority and submission to Christ, which stands in stark contrast to Hadrian's full, philosophical beard as emperor of Rome. |

As the Middle Ages evolved into the Renaissance, the history of beards becomes far more tangled. Influential figures like Henry VIII and Martin Luther grew defiantly powerful beards only to have their hairy rebellion cut short by the dominance of French fashion’s clean shave in the court of Louis XIV. From here on the place of facial hair in society becomes more difficult to locate, as it was employed by both rebels and popular icons, mustachioed German cavalry and roguish Hollywood movie stars. The final chapters show a hodgepodge of beard cultures in the strictly shaven group orientation of corporate America from the unkempt hair of the hippies to the emerging gender bending beards of metrosexuals and transsexuals.

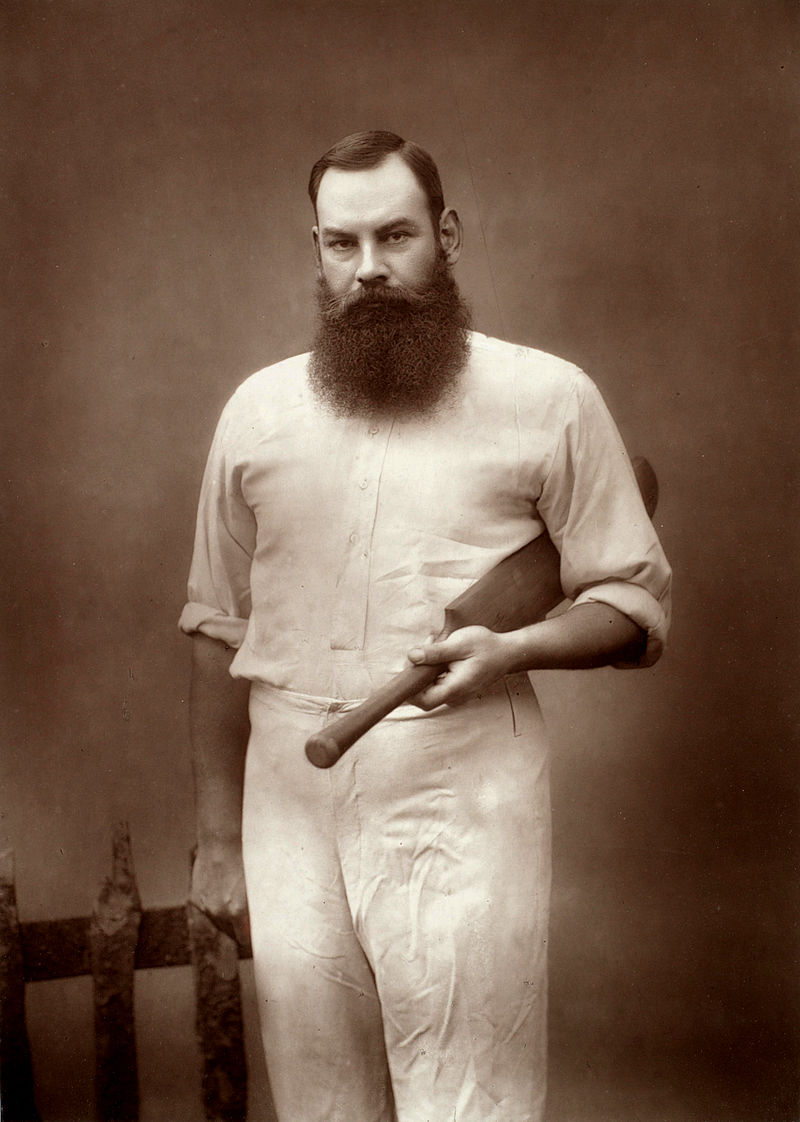

|

| The famously burly W.G. Grace was one of Britain's most famous cricket players who stood out from the crowd with both his imposing career and his imposing facial hair. |

This long history is conveyed with wonderful style as an extended series of snapshots that are divided between thirteen period-defining chapters. With clever puns and a narrative twist Oldstone-Moore draws a consistent line between the ideals of masculinity and its expression through facial hair across the ages.

The choice of evidence presented in the book remain somewhat patchy. Although the author has taken a great deal of time and effort to highlight some of the many various styles of facial hair which defined masculinity, he has done so with a decidedly Eurocentric bent. Beards and mustaches present throughout East Asian and African history remain largely unaddressed, as do ethnic cultures in Polynesia and the Americas where facial hair was not a common trait and masculinity would have been defined by other factors.

Even so, such an argument could be considered splitting hairs. The author’s choice to focus on a Western or European history of beards does far more to highlight the relevance of facial hair as a tool to trace cultural shifts than it does to detract from the limited scope of Oldstone-Moore’s work. This book opens the door for a great deal of further development by future publications.

While his foundational assertion that facial hair has been used as a universal symbol for varying ideals of masculinity is fairly clean cut, his claim to identify four distinct beard movements presents a hairier problem. Very clear distinctions between the bearded and the shaved early on in the book become difficult to trace as adoptions of facial hair become increasingly complex. Control of the masculine remains consistent throughout this history, but the neatness of earlier chapters becomes much less well-groomed as the book progresses and multiple cultures of facial hair take place in overlapping regions and periods. Nonetheless, this is an accessible and entertaining read which would complement any bookshelf.