Not too long ago commentators regularly talked about the end of the nation-state. Internationalism—whether through global trade agreements or the expansion of organizations like the European Union and NATO—seemed triumphant. Today, not so much. Countries from the Philippines to Hungary, from Turkey to the U.S. have been swept up in a reactionary nationalism. The United States has embodied this tension. Having been at the forefront of creating institutions of global governance, Americans have aggressively rejected them at the same time. This month historian Amanda Lawson looks at this century-long friction between the need for global governance to protect human rights and the demands of national self-interest.

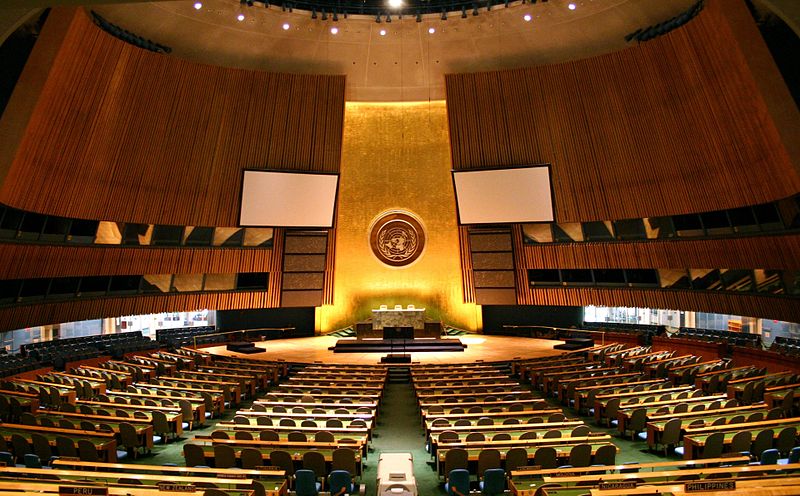

In September 2018, President Donald Trump delivered a speech before the United Nations General Assembly. Humanitarian concerns were at the center of every crisis he mentioned, from immigration at the U.S.-Mexico border to social reform in Saudi Arabia.

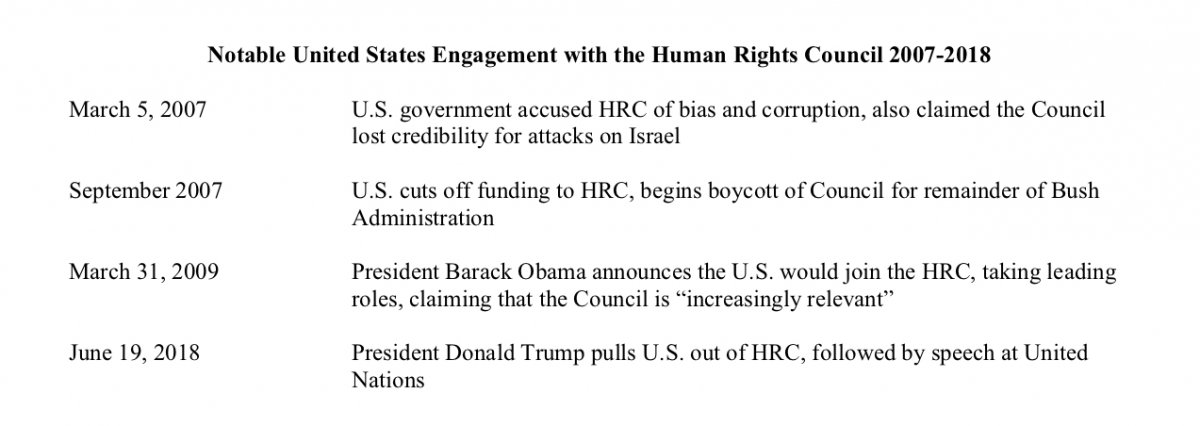

Yet Trump offered a pointed critique of the United Nations, and specifically the Human Rights Council (HRC) and the affiliate International Criminal Court (ICC). Trump accused the HRC of shielding human rights abusers and denied that the ICC had any authority or jurisdiction.

United States leadership has been crucial to the UN from its inception. So why would the president deliver such a harsh critique? The answer lies at the intersection of global governance and Trumpian neo-nationalism.

The very idea of global governance raises two big issues, both centering on how nations define their sovereignty. The first concerns diplomacy and how conflicts between states can be avoided. The second issue is how individuals inside nation-states are treated by their own governments and what can be done when governments violate individual rights.

The logo for the UN Human Rights Council (left) and the International Criminal Court (right).

In either case, adherence to the standards and rules imposed by a global body requires national leadership to yield some power. All governments are reluctant to do that.

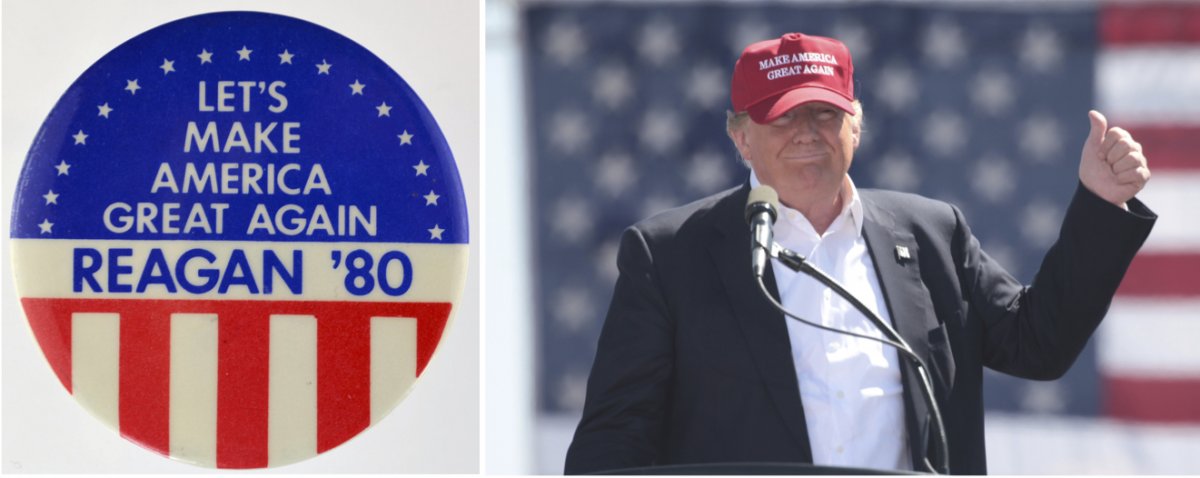

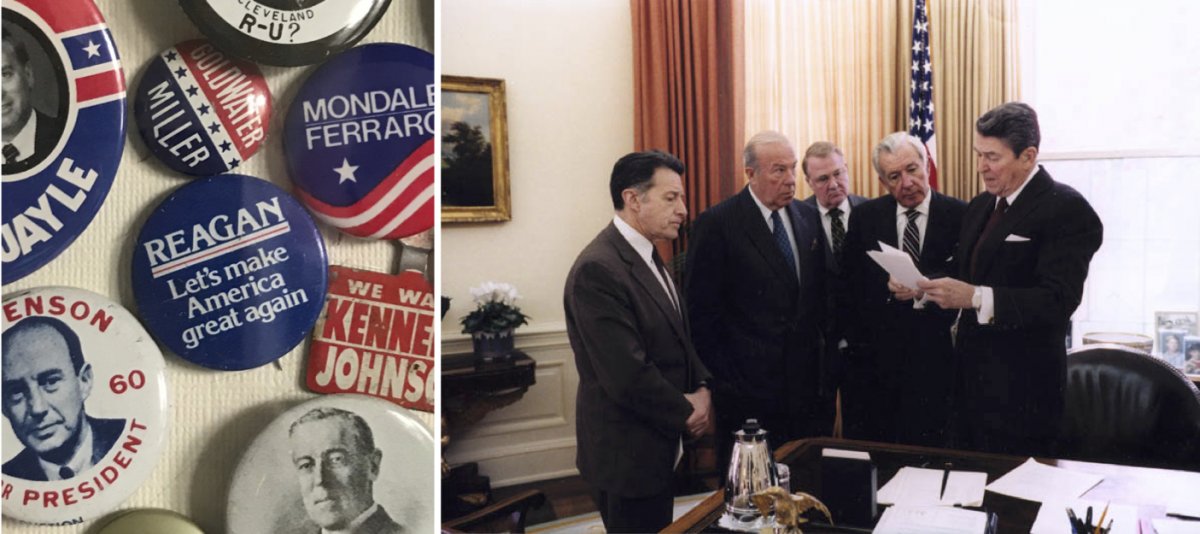

Trump is certainly not the first U.S. president to question the authority of international governing bodies. His campaign slogan, “Make America Great Again,” is a direct nod to the approach of President Ronald Reagan (1981-89), who was also deeply suspicious of the notion that the United States was beholden to a governing body outside of Washington, D.C.

A button from Ronald Reagan’s 1980 presidential campaign (left). Donald Trump wearing one of his iconic “Make America Great Again” hats during the 2016 campaign (right).

Trump’s critique of the UN, therefore, is part of a long-running battle in the United States between those who see the need for international governing bodies and those who think only national self-interest should govern international affairs.

World War I: Modern Origins of Nationalism and Global Governance

The starting point in the discussion of this conflict is President Woodrow Wilson’s vision of the world after WWI.

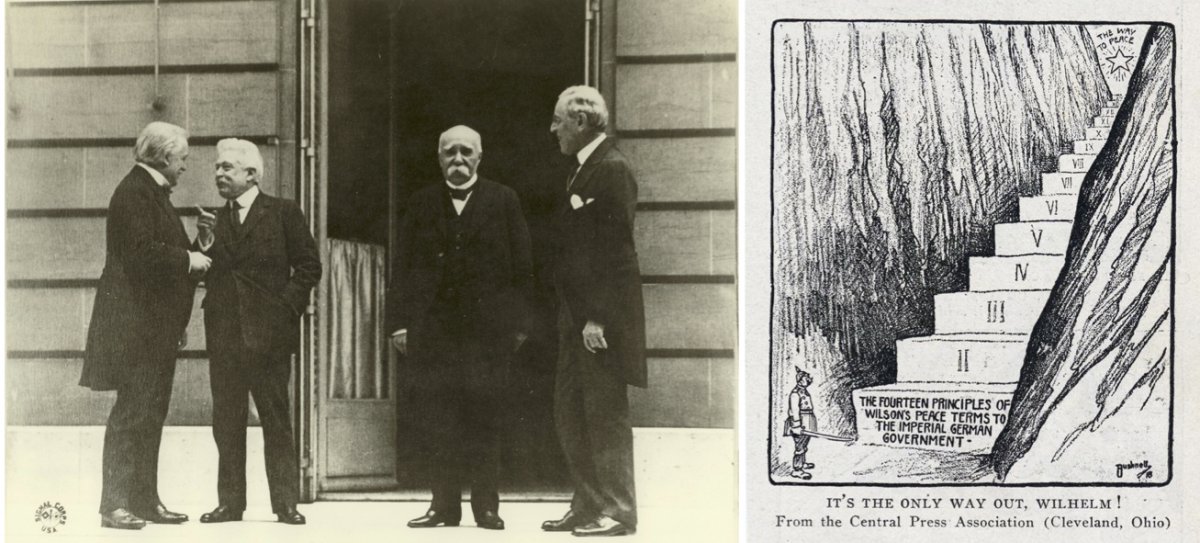

Wilson arrived at the Paris Peace Conference with his Fourteen Points, a plan that he believed would bring justice to offenders, recovery to victims, and through the creation of the League of Nations, lasting peace to the world. The League would be an international governing body that would supersede individual national ambition—therefore preventing another global war.

From left to right, Prime Minister David Lloyd George of Great Britain, Prime Minister Vittorio Orlando of Italy, Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau of France, and President Woodrow Wilson at the Paris Peace conference in 1919 (left). A 1918 political cartoon depicting Kaiser Wilhelm II considering Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points as a path to victory (right).

At the same time, Wilson helped inspire a wave of nationalism when he promoted national sovereignty among ethnic groups who were minority populations in larger empires.

Speaking to an international audience in Paris, he denounced imperialism—especially in Africa and Southeast Asia. Following the speech, many colonial territories viewed the Peace Conference as an opportunity to press for their own rights on a global stage.

By the end of the war, four powerful multi-ethnic states in Europe—Ottoman, Austro-Hungarian, Russian, and German—had fallen, providing an additional push for self-determination-minded nationalist movements.

While the president intended his promotion of self-determination to be for a specific set of nations rather than a blanket statement for countries worldwide, his words had a dramatic influence across the globe. Wilson himself embodied the tension between nationalist and international dreams.

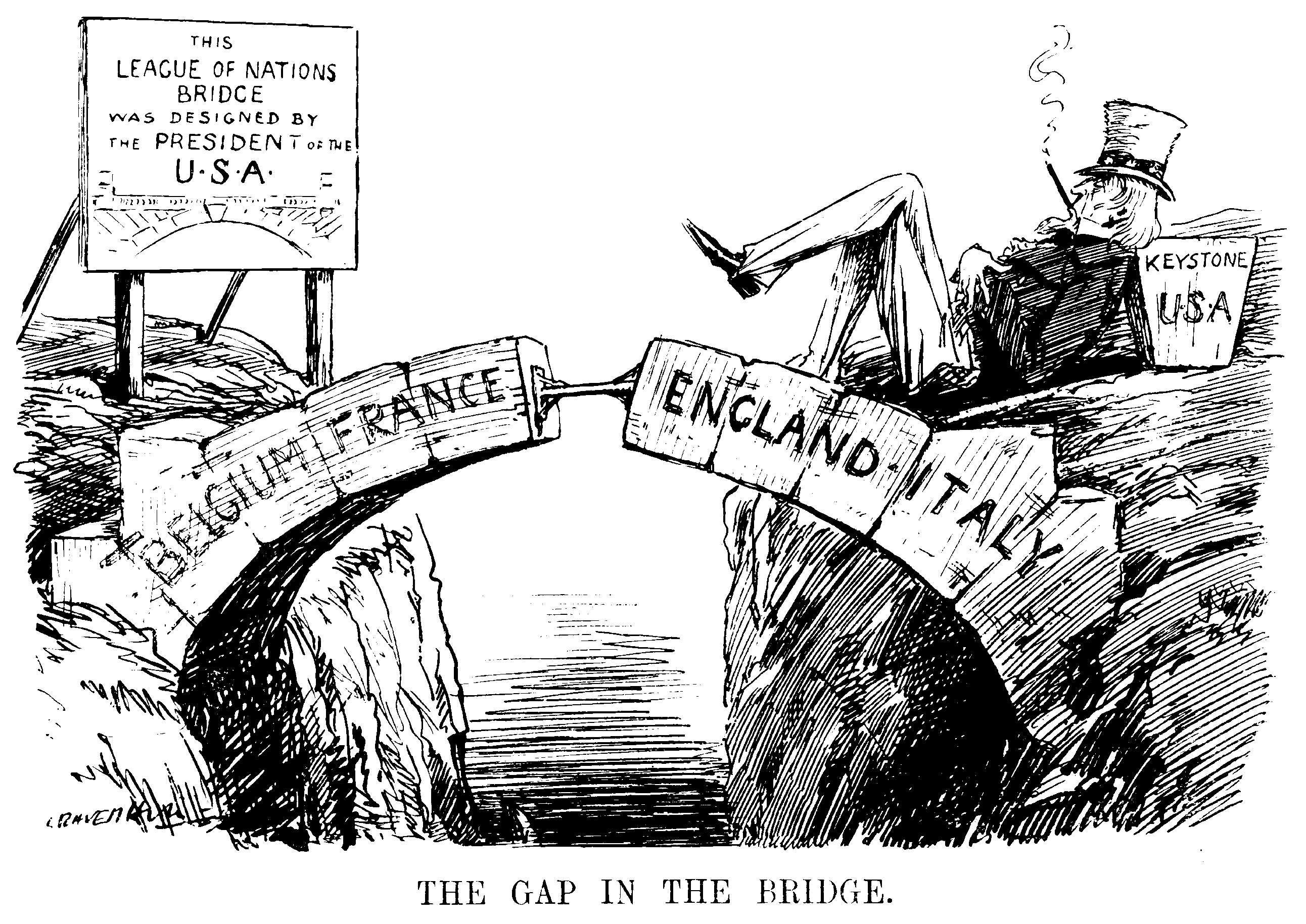

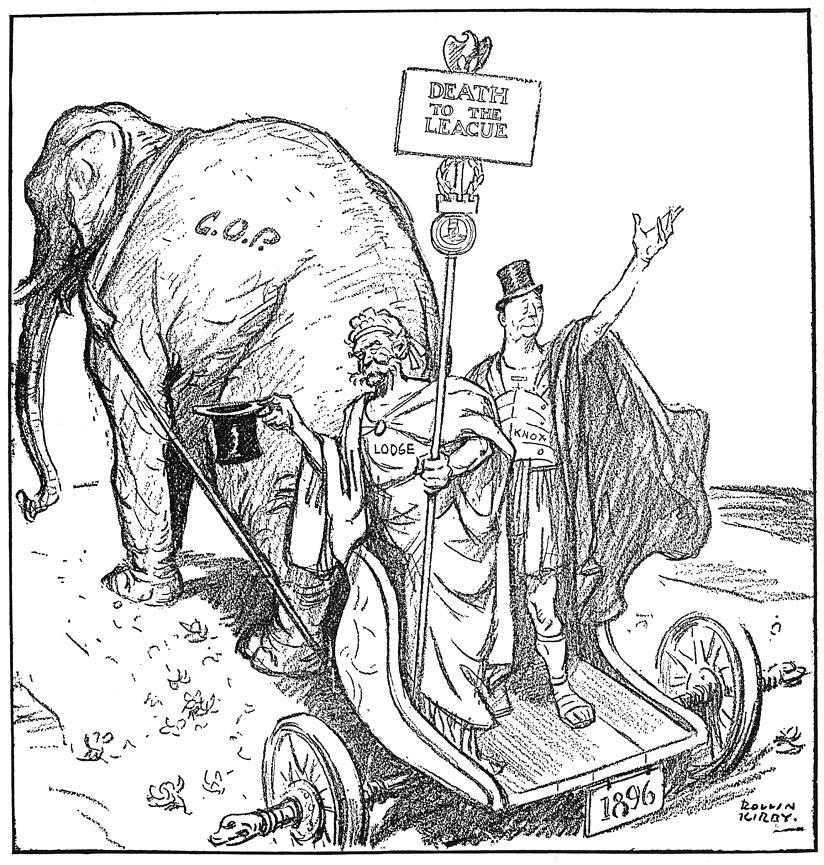

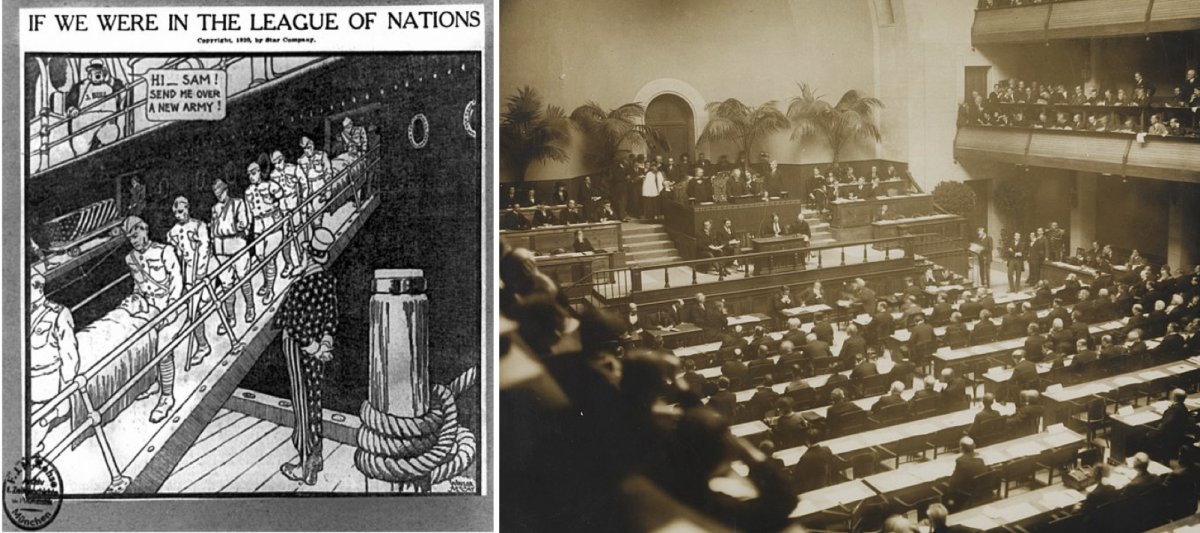

When Wilson brought the Treaty of Versailles to the U.S. Senate for ratification many politicians objected to the idea of the League of Nations on the grounds that this form of international authority was an infringement on national sovereignty. Senator Henry Cabot Lodge led the opposition, listing, among other reservations, that the United States should have the exclusive right to determine laws and address domestic issues without interference by an external body.

Lodge worried that the League would impinge on American national sovereignty. He also attributed his distaste for the League to its ability to mandate military action, collect fees, and regulate foreign trade.

In the end, 63 nations joined the League, including powerful nations and American allies, but the deeply divided U.S. Congress rejected the League and prevented U.S. participation in this global organization.

A 1920 political cartoon of John Bull, representing Britain, demanding more U.S. soldiers just as they were returning from overseas combat (left). The opening session of the League of Nations in 1920 (right).

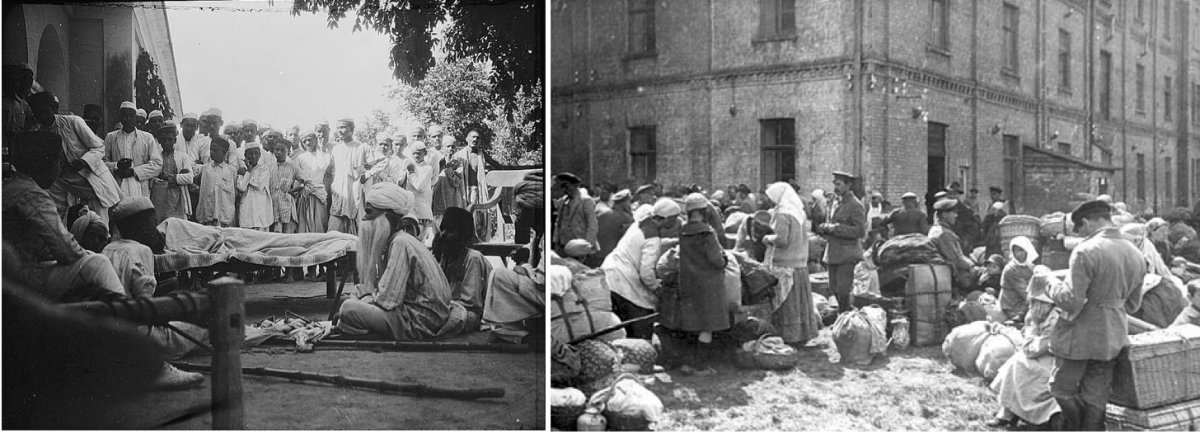

Even without U.S. involvement, the League of Nations did see some success in the post-WWI years, most notably in its humanitarian efforts. It brought scientists together to work on prevention of diseases including malaria and leprosy; it rescued 400,000 prisoners of war; and it mediated disputes throughout Europe and Asia, among other accomplishments.

The League’s original charter also included clauses for involvement of non-governmental organizations (NGOs). These organizations were instrumental in relief efforts and laid the foundation for an even larger role in global governance after the creation of the United Nations.

A time-lapse map showing the members of the League of Nations throughout its history.

One NGO in particular was the International Committee of the Red Cross, which received a mention in the Charter of the League of Nations, along with a recommendation for its consultation in humanitarian affairs. NGOs transcended national boundaries—as did the crises to which they attended—and set a precedent for intervention in international affairs.

The League of Nations championed the concept that there were issues of universal scale that could be addressed in a global community. Most importantly, it laid important foundations for how nations could negotiate problems and differences through a global institution.

A 1929 anti-malaria investigation by the League of Nations in India (left). The International Committee of the Red Cross in Latvia assisting in the repatriation of Russian, Latvian, Gemerna prisoners of war in the 1920s (right).

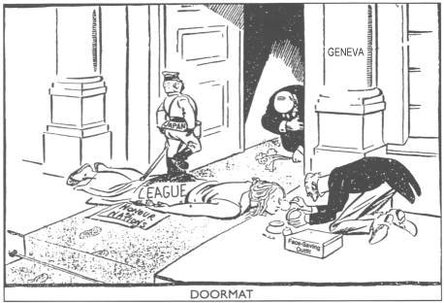

But the League of Nations did not create a more peaceful world. Less than 20 years after the Paris Conference, Nazi Germany had overrun much of Europe and Imperial Japan had conquered large swaths of East Asia and the Pacific.

The world was once again thrust into a conflict that brought the debate over national sovereignty and global governance to the forefront. Because it seemed impotent to prevent the Second World War, the League has been seen as a failure and a clear example of the inability of international institutions to govern world affairs.

A 1933 political cartoon showing Japan walking over the League of Nations.

World War II: Evidence for Need of Global Governance

However briefly, World War II reversed the American impulse toward isolation that kept it from joining the League of Nations. The scale of the war’s destruction created a shared understanding that recovery from such devastation would take much more than a national effort. The idea of a global governing body returned.

Even before the United States officially joined the war, world leaders were working on an international response that would aid in both the recovery of nations and preservation of peace in the postwar period. President Franklin Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill met in August 1941 to discuss how their nations would contribute to postwar relief and reconstruction efforts. The result of their meeting was the Atlantic Charter.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill meeting in 1941 onboard the HMS Prince of Wales for what became known as the Atlantic Charter meeting.

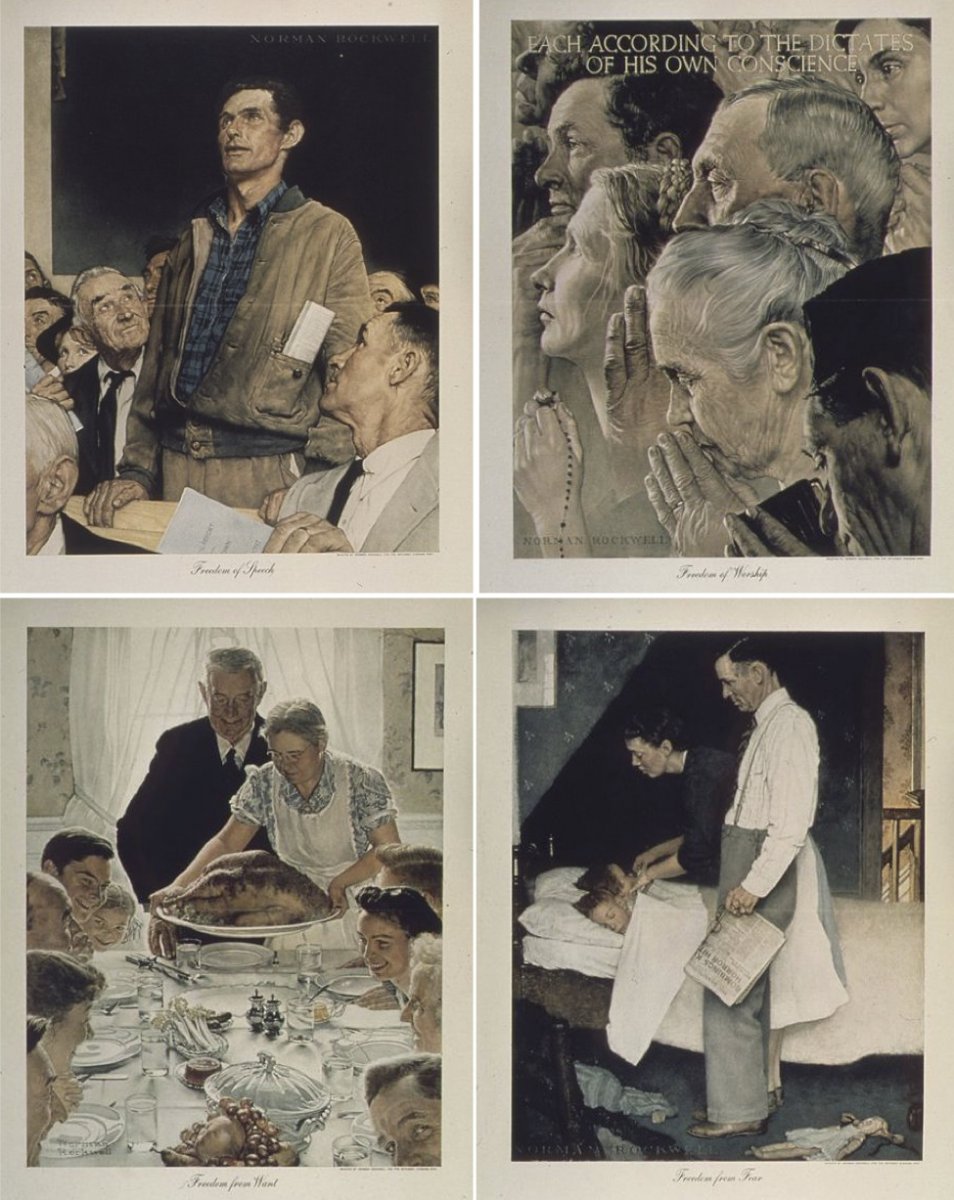

That document was based on Roosevelt’s 1941 State of the Union Address. He outlined four key freedoms that all people should enjoy: freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom from want, and freedom from fear. The four freedoms were the basic human rights around which Roosevelt and Churchill thought the postwar world should be built. The Atlantic Charter closely mirrored this.

The significance of the Atlantic Charter for human rights in the 20th century cannot be overstated. The document provided the foundation for the United Nations Charter, which would be codified in June 1945.

Norman Rockwell’s 1943 depiction of the four freedoms.

The Atlantic Charter represented a dramatic shift in favor not only of human rights, but of global accountability and cooperation. It was fundamentally different from attempts following World War I. While Wilson had sought a world where nations worked out differences in an international forum, Roosevelt and Churchill wanted to ensure that individuals’ human, not simply national, rights were respected and protected.

Seizing the Opportunity: The Creation of the United Nations

As the war neared its end, representatives from the Allied Powers attended a series of meetings in Bretton Woods, Dumbarton Oaks, and San Francisco. Their purpose was to create a supra-national organization that would accomplish what the League of Nations set out—but failed—to do: bring recovery from war and preserve global peace thereafter.

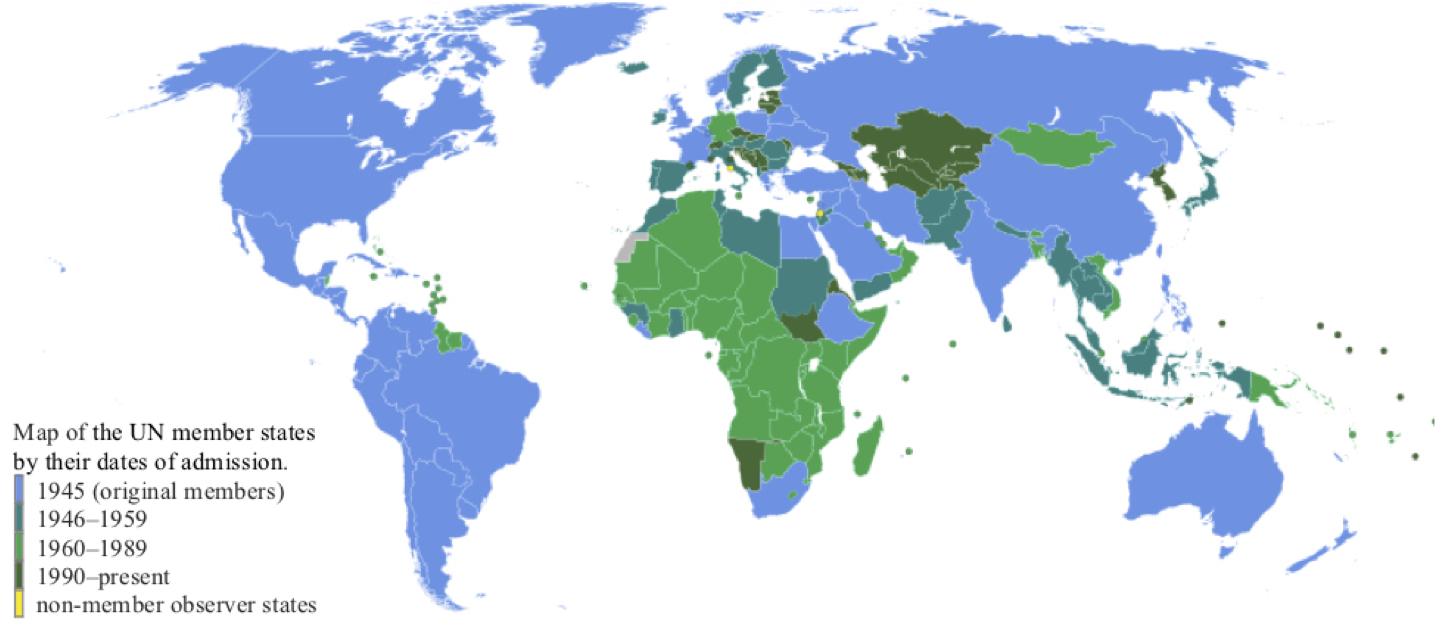

All nations were invited to join, including small and newly independent ones. Looking back to the Paris Peace Conference after World War I, many leaders of small nations felt left out of matters that would shape global events affecting their countries. The UN gave those countries opportunities to participate effectively and ensure that humanitarian concerns in developing nations would not be overlooked.

A map of UN member states by the date they joined.

But for larger, historically dominant, and authoritative countries, global governance—at least, if it were to succeed—required a measure of sacrifice. The more countries that could vote, the less significant each individual vote. Additionally, global governance meant that for these more developed countries, adherence to the body’s decisions could mean accepting rulings that superseded national authority or ran counter to national interests.

A 1945 UN poster about the makeup of the Security Council.

The creation of the Security Council was one way to assuage these concerns. Fifteen nations sit on the council, five permanently, while six serve for two-year terms (the number of rotating seats was increased to ten in 1965). The five permanent members (the United States, the United Kingdom, Russia, China, and France) each have veto power to stop any vote, which can, among other things, halt military action by UN forces. The distinction between the permanent and rotating members of the council was one way in which larger countries sought to mediate this power dynamic.

If preventing war was the first rationale for the United Nations, promotion of human rights and international development followed close behind.

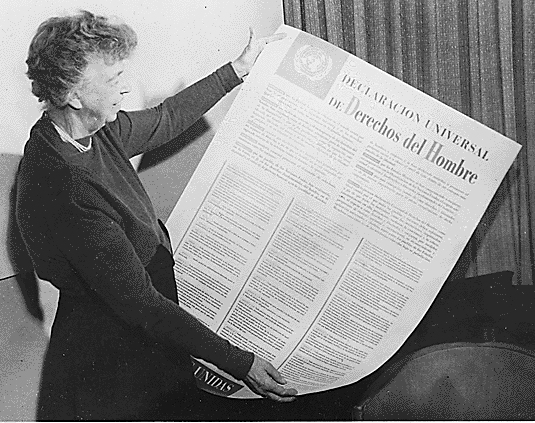

In 1946, the UN established the Commission on Human Rights. In 1948, under the direction of former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, a United Nations commission drafted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The Declaration, though produced by an organization of nation states, asserted that individuals had a set of specific rights and that they held those rights regardless of nationality, gender, religion, and race. It stands as the most comprehensive call for human rights in modern history.

Former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt holding the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1949.

The signing of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights came one day after the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (the United States did not sign the Genocide Convention until 1988).

Both of these UN documents signaled two significant changes in global politics: 1) that an international body could establish universal principles to which nations could be held accountable, and 2) that there would be ramifications for violating those principles.

Essentially, the United Nations codified global societal rules and international accountability. It also connected human rights and humanitarian affairs to national security, on the grounds that people who were satisfied and well taken care of were less likely to revolt or seek asylum outside of their home country.

Early Cold War: National Foreign Relations in an Era of Global Governance

Unfortunately, the UN’s ability to keep peace was almost immediately challenged by the rising tensions of the Cold War. While there were some military actions, the Cold War primarily launched the world into an ideological battle that tested the resolve of the United Nations and leaders who had supported the push for global human rights. Global leaders were often faced with a choice between supporting democratic left-leaning regimes or capitalist authoritarian juntas.

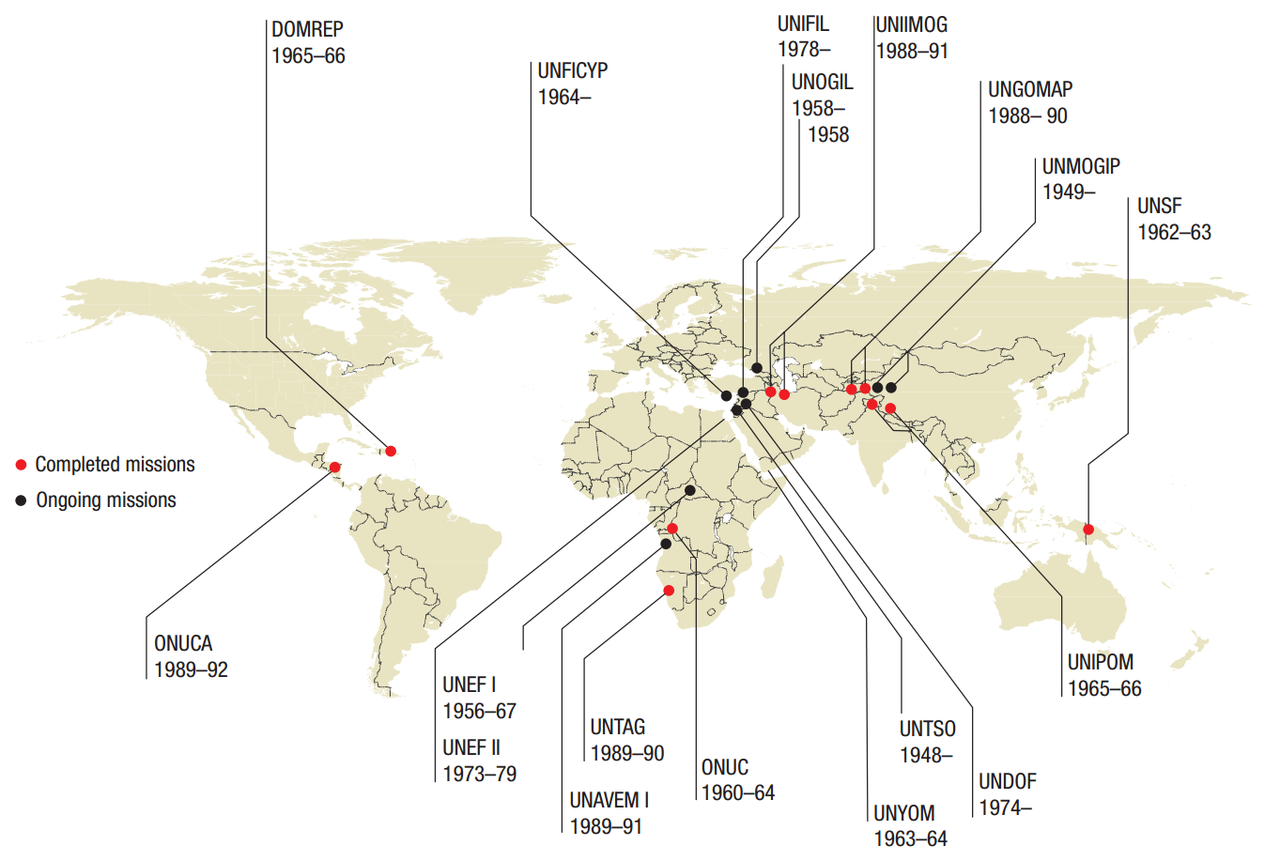

A map showing UN Peace Operations during the Cold War.

The Korean War (1950-1953) became the first global conflict of the post-WWII age. After the invasion of South Korea by the North, the Security Council met to consider a response. It created a UN-mandate force to fight the invasion and in the end 21 UN-member nations, led by the United States, contributed to the military effort.

When the issue was brought to the Security Council, however, the Soviet Union was not present—it was boycotting the United Nations altogether—and thus did not veto the resolution. In its first test of global authority, the United Nations functioned well, even if the war ended in a stalemate that endures to this day.

The Vietnam War (1955-1975), on the other hand, demonstrated the limitations of the United Nations’ ability to keep military peace when powerful nations became involved in conflict. Just as the war itself was a proxy for hostilities between the capitalist and the communist worlds, so too the Security Council became a place for ideological fights between the five permanent members. Consequently, the United Nations played very little role in the Vietnam War as it escalated or in the negotiations for a resolution to it.

The Cold War also revived calls for national sovereignty against the institutions of global governance.

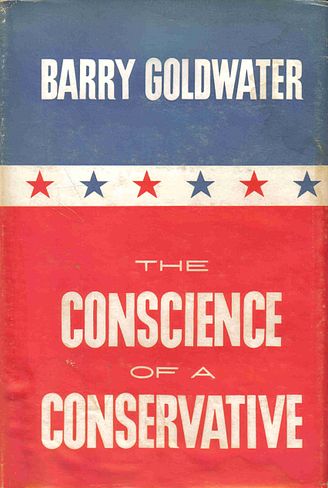

In his 1960 book, The Conscience of a Conservative, future presidential candidate Barry Goldwater rejected global governance in favor of a strong show of nationalism and national sovereignty. Goldwater criticized the UN for giving too much authority to communist countries like China and the Soviet Union and called for the United States to take an aggressive approach to dealing with those countries on the international stage. He was a frequent critic of the concept of global governance and tied intense nationalism to a distrust of a supra-national government as a tenet of American conservatism.

From Vietnam to Helsinki

If the United Nations failed to prevent or end the Vietnam War, the war inadvertently contributed to a renewed call to protect human rights. Especially after images from My Lai were printed in American and European newspapers, questions about war crimes and military accountability flooded into domestic and international debates.

A photograph of the aftermath of the 1968 mass murder of unarmed South Vietnamese civilians by U.S. troops (left). Captain Ernest Medina, commander of the Army unit responsible for the My Lai Massacre, speaking with reporters after a Pentagon investigation in 1969 (right).

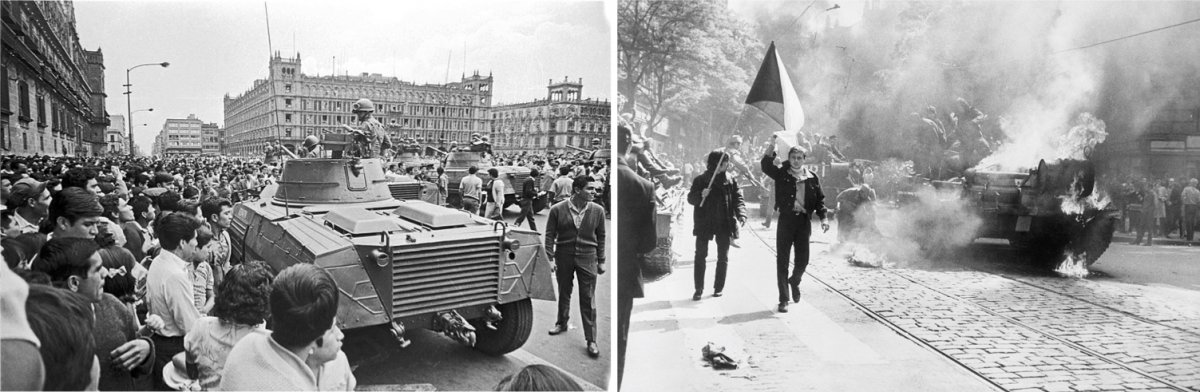

The My Lai Massacre, as it came to be known, happened in March 1968. That same year, the world seemed to be engulfed in humanitarian crises from My Lai to Tlatelolco to Prague. The events of 1968 led to the global human rights movement of the 1970s.

Early in the decade, outrage over military actions in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos, along with controversy surrounding covert U.S. involvement in Latin America, further instilled the need for nations to be held accountable for violations of human rights.

A tank and student protestors in Mexico City’s Plaza de la Constitución in August 1968, two months before the Tlatelolco Massacre (left). Protesters in Prague during the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 (right).

The Helsinki Accords, signed in 1975, represented the global governance of human rights and established the high value of human rights for the global community. The Accords gave governments new international accountability for humanitarian practices within their borders.

The United States used these new global government regulations on human rights as an opportunity to challenge the Soviet Union’s domestic policies. In this case, the United States was completely supportive of the ability of a global community to direct a sovereign nation to comply with international legislation.

As a result of the Helsinki Accords, human rights came to signify more than the right to live. They encompassed bodily safety, political rights, and the socioeconomic freedoms Roosevelt articulated in 1941 and which his wife championed seven years later. It represented a global understanding of human rights standards and a general consensus that crossed the deeply entrenched ideological lines of the Cold War. The commitment to the Accords set a precedent for the international community.

When Jimmy Carter became president in 1977, he moved his administration to further support human rights policy and international governance. Speaking about the interaction between national sovereignty and global governance on humanitarian issues, one Carter official remarked, “[I]t is possible to advance the rights and meet the basic human needs of individual human beings while at the same time respecting the sovereignty of their government.”

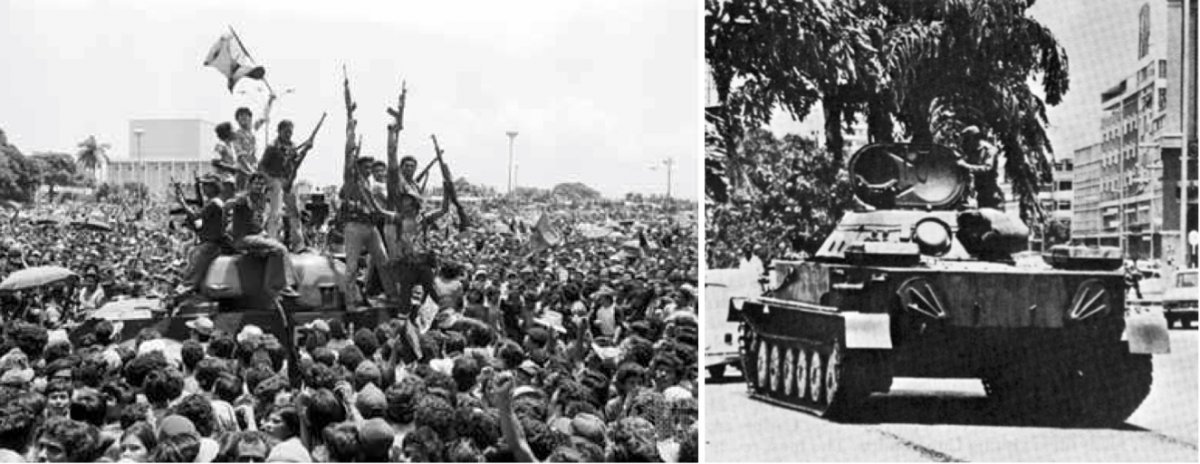

Sandinistas celebrating in Nicaragua in July 1979 (left). A Cuban tank in Angola in the 1970s (right).

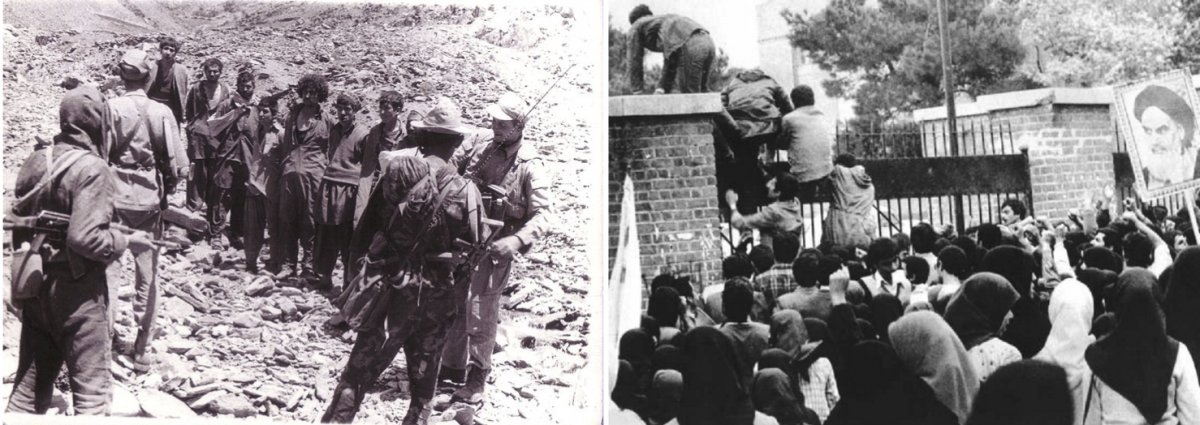

But this brief period of successful and humanitarian global governance hit a wall in 1979. The Sandinistas revolted in Nicaragua; Castro sent Cuban troops to Angola to support a communist revolution; the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan; and Iranian students stormed the U.S. embassy in Tehran, taking more than 60 hostages in protest of the United States. The UN Security Council was again paralyzed by disagreeing permanent members.

The events of 1979 paved the way for a resurgence of Cold War fears that predicated a rise of U.S. nationalism. Sandinistas in Nicaragua were fighting against an oppressive dynastic government run by Anastasio Somoza. Somoza was sympathetic to capitalism and but was corrupt and forcefully withheld aid from his people, which, after signing the Helsinki Accords, the United States could not ignore.

Soviet soldiers after capturing Mujahideen fighters in Afghanistan in the 1980s (left). Iranian students storming the U.S. Embassy in Tehran before taking U.S. hostages in November 1979 (right).

Cuban support of a Marxist revolution in Africa threatened capitalist nations in the UN. When the Soviets invaded Afghanistan, the United States supported the Afghani Mujahedeen fighting against the Soviet army. Amidst a failed hostage-rescue attempt, the already bubbling tensions in Iran and Iraq came to a boil. The 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq War tore the Middle East apart, and U.S. covert involvement in the Iran-Contra Affair damaged both U.S. and UN credibility on the global stage.

Ronald Reagan used the events of 1979 to argue that the Carter Administration allowed the nation to become weak and open to national security threats. He believed that the humanitarian emphasis of Carter policies and the administration’s willingness to yield to UN governance damaged U.S. authority and power.

A campaign button from Ronald Reagan’s 1980 presidential campaign (left). President Ronald Reagan in the Oval Office discussing remarks on the Iran-Contra affair with aids Caspar Weinberger, George Shultz, Ed Meese, and Don Regan in 1986 (right).

His solution hinged on a revitalization of American nationalism. His campaign slogan, “Let’s Make America Great Again,” and his promises to build up American strength, made nationalism synonymous with national security. He played into the fear surrounding the Cold War and implications of the crises of 1979.

The success of his campaign ensured that a heightened sense of nationalism and prioritization of sovereignty would be foundational to the Republican Party platform for decades to come.

Post-Cold War: UN Promotion of Justice and Human Rights

After the Cold War ended (1989-1991), one of the most successful initiatives undertaken by the United Nations was the establishment of the Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda in 1994. The court prosecuted the leaders of the Rwandan genocide that took the lives of between 800,000 and 1 million people over the course of 100 days in 1994. The tribunal handed down 93 indictments.

The UN Security Council establishing the International Criminal Tribunal for Yugoslavia in 1993 (left). The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda in 2003 (right).

Similar tribunals exist for crimes in the former Yugoslavia (present day Croatia, Slovenia, Serbia, Macedonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Montenegro) and Cambodia. The success of the tribunals established support for human rights and justice for violators.

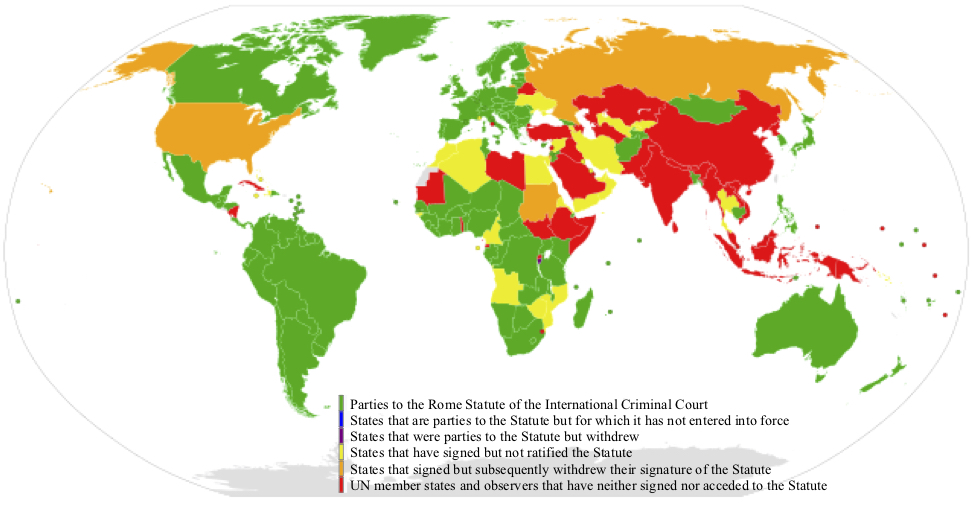

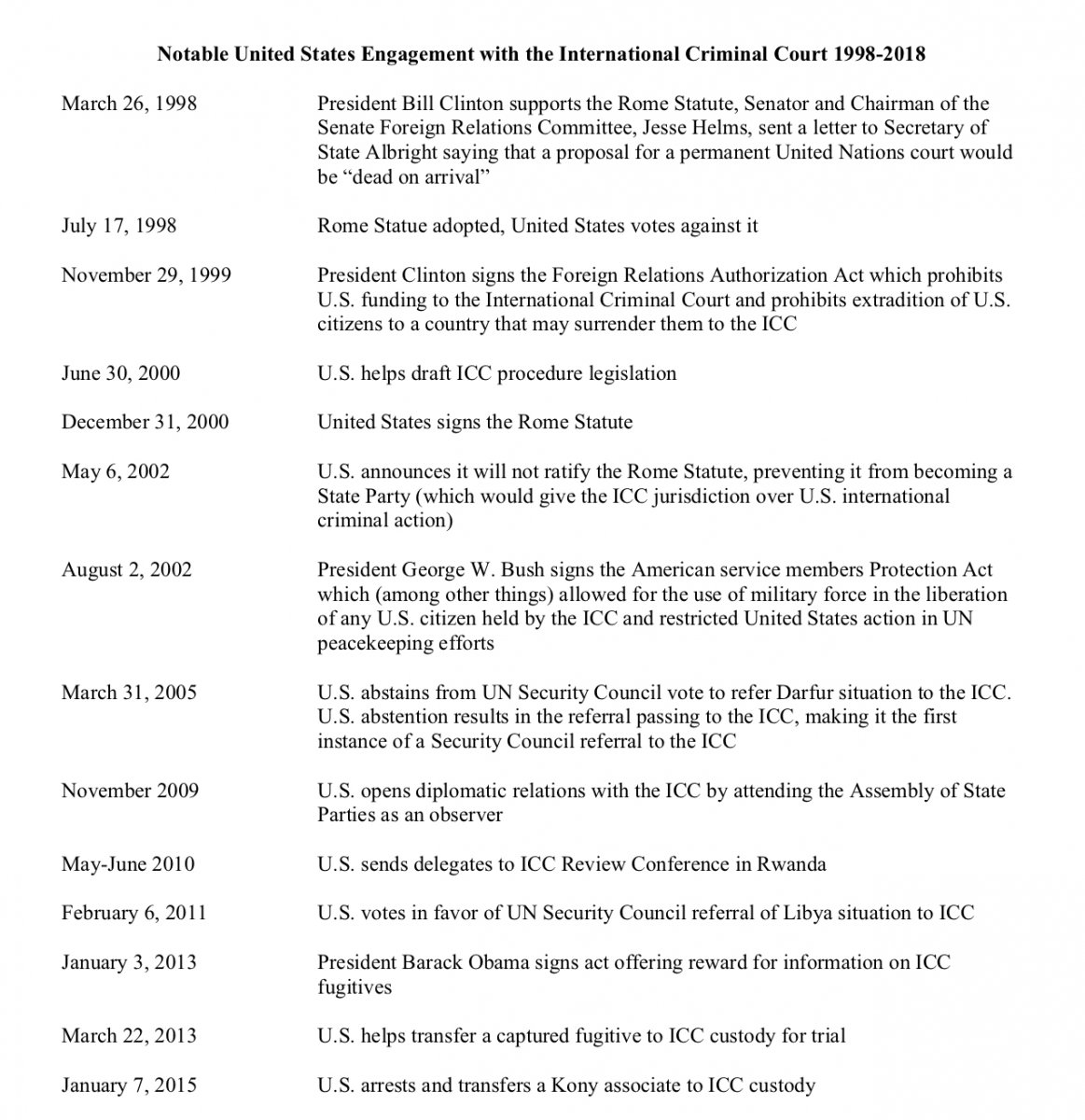

The foundations for the International Criminal Court (ICC) arose during the UN tribunals in Yugoslavia and Rwanda. The ICC was created by the Rome Statute in 1998 and took effect in 2002.

The International Criminal Court building in the Hague.

The Court tries individuals, rather than nations, and is the only permanent international criminal tribunal with a mandate to investigate and prosecute cases. It pursues cases on four fronts: genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and crimes of aggression. Like the United Nations, the International Criminal Court relies on the cooperation of individual nations to enforce its decisions.

The United States has had a tumultuous relationship with the ICC, going back and forth between supporting the Court and rejecting it over concerns about national sovereignty. The United States was instrumental in establishing the Rome Statute, yet was not one of the 120 nations to sign the treaty recognizing its authority.

Parties and signatories of the Rome Statute as of 2013.

The Court itself states that it is “intended to complement, not to replace, national criminal systems; it prosecutes cases only when states do not, are unwilling or unable to do so genuinely.” Nevertheless, Presidents Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Donald Trump all struggled over the extent to which the United States would heed ICC action. In a statement against the Court during his September 2018 UN speech, President Trump promised “we will never surrender America’s sovereignty to an unelected, unaccountable, global bureaucracy.”

The Human Rights Council—formerly the Commission on Human Rights—was reconstituted in 2006. The HRC's primary mandate covers terrorism, discrimination, indigenous peoples’ rights, food security, the fight against torture, and promotion of technical cooperation in favor of human rights. It focuses on situations that cross national boundaries and influence the international community.

The opening session of the 2018 session of the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva, Switzerland.

Since its inception, the Council has held 28 emergency sessions and launched 27 fact-finding missions with ongoing missions to Syria, Myanmar, South Sudan, Burundi, Yemen, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. These missions serve to monitor and report on humanitarian concerns to which the United Nations should respond.

The chairperson of the fact-finding mission to Myanmar harkened back to some of the original principles of global governance when he explained the role of the HRC, saying that “when accountability is unattainable domestically, impetus must come from the international community.” His statement situated the Council in the gap between national sovereignty and global governance.

By turning a “commission” into a “council,” the UN gave the HRC more authority to act, rather than serving primarily in an informational capacity. When the UN member states voted to replace the Commission on Human Rights with the Human Rights Council, 170 nations voted in favor, three abstained, and four voted against it—the United States, Israel, the Marshall Islands, and Palau.

A Decisive Shift or Part of a Pattern?

President Trump explained the United States’ withdrawal from the Human Rights Council in his speech before the UN General Assembly in September 2018. He called out the Council for its consistent pressure on Israel while also “shielding egregious human rights abusers.” The Human Rights Council has been particularly attentive to violations occurring in Israel, and George W. Bush made much the same charge.

In rejecting globalism and asserting that global institutions threatened American national sovereignty, Trump also echoed complaints that have been heard before if not in quite such direct terms as when he contended against the International Criminal Court: “[A]s far as America is concerned, the ICC has no jurisdiction, no legitimacy, and no authority.”

A Nepalese soldier patrolling while pallets of humanitarian aid drop in Haiti in 2010.

In reality, American presidents from both parties have questioned the role of international bodies since the founding of the League of Nations.

Opposition to global institutions has become a key pillar for conservatives and for the Republican Party. The 2012 GOP platform, under a heading titled “American Exceptionalism,” declared that the UN agenda was “erosive of American sovereignty.”

But in this critique of the current structure of global governance, the United States was not all that exceptional. With its vote to leave the European Union, the United Kingdom has similarly decided international arrangements impinged on its national sovereignty.

Ironically, if some Americans have complained that the United Nations and related institutions threaten national sovereignty, others have complained, not without cause, that the UN has been ineffective because it has not been able to carry out the international will against individual nation states.

But for nations that are now free from oppressive rulers and rid of diseases thanks to the work of international organizations, for those nations that are now significantly more developed, and for those whose citizens feel protected by the blue helmets of UN peacekeepers, global governance has been a tremendous success. It has given a voice to smaller nations and held—at least, to an extent—larger ones accountable. It has provided a space for the global community to discuss matters that are truly universal, and this is where human rights have found their champion.

The UN General Assembly hall in New York City in 2012.

That is not to say that there isn’t need for reform and those reforms must surely involve the engagement of the United States. The United States was central to the founding and development of the UN system of global governance and it maintains its permanent membership on the Security Council. But the question remains whether the imposition of opposition between national sovereignty and global governance is inevitable or if the two can coexist.

Read more from Origins: United Nations Peacekeeping; Genocide and Rwanda; On the Armenian Genocide; the Genocide Question; and Refugees: Past and Present

Bolton, John. Surrender Is Not an Option: Defending America at the United Nations. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007.

Borgwardt, Elizabeth. A New Deal for the World: America’s Vision for Human Rights. Cambridge, MA: Belknap, 2005.

Critchlow, Donald. Conservative Ascendency: How the GOP Right Made Political History. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007.

Critchlow, Donald. Republican Character: From Nixon to Reagan. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018.

Goldwater, Barry. Conscience of a Conservative. Shepherdsville, KY: Victor Publishing Company, 1960.

Manela, Erez. The Wilsonian Moment: Self-Determination and the International Origins of Anticolonial Nationalism. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

O’Sullivan, Christopher D. Colin Powell: American Power and Intervention from Vietnam to Iraq . Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2009.