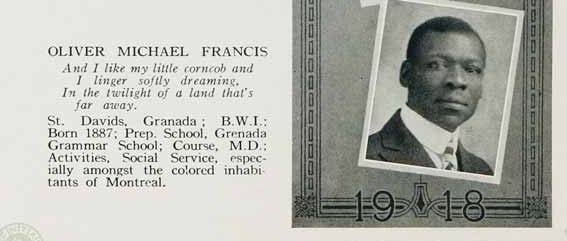

In 1918, Grenadian-born Oliver Michael Francis was a medical student at McGill University. Biographical profiles in Old McGill, the university’s yearbook, included country of origin, date of birth, schools attended, and extra-curricular activities.

Oliver Michael Francis's entry in the 1918 McGill University yearbook.

Francis’s extracurricular activities were striking. While the majority of Caribbean students were involved in a variety of sports and clubs, Francis was involved in “social services especially among the colored inhabitants of Montreal.”

It is possible that in choosing to volunteer in the Black community, Francis was aware of its marginalization. Being from the Caribbean, however, he might have not recognized the fringe position Black Montrealers occupied in the province.

Given the lack of writings regarding the impact of the 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic on Black Canadians, we do not know whether Francis was directly involved in caring for Black Montrealers infected with the illness. Only the historical imagination and speculation can attempt to answer that question.

Whether or not Francis offered his help to Black flu victims, his stay in Canada prompts a haunting question that is relevant in this moment as COVID-19 and brings into sharp relief Black Canadian vulnerability.

Is it possible to write about those who perished in the 1918 pandemic when the living—then and now—actively deny their existence? Equally important: what happens to populations that the archives do not account for and how can we use our creative imaginations to bring the lost past to life?

Such are the dilemmas of writing the history of Black Canadians—present and yet absent at the same time.

The Evening News headline for October 26, 1918 in Halifax.

Studies of pandemics have repeatedly illustrated the correlation between economic status and mortality rates. Racialized groups in particular have borne the brunt. In Canada, some villages were decimated by the disease. First Nations reserves were disproportionally impacted as well as cities such as Toronto, Montreal, and Halifax. Approximately 55,000 Canadians died. The number of Black Canadians is unknown, a fact that could be attributed to the fact that influenza was not a reportable disease.

Still the general erasure of Black people from pandemic historical narratives is connected to their place within the nation. Despite centuries of being on Canadian soil, Black people have encountered racism, racial stratification and de facto segregation albeit at varying levels.

The types of low wage work available to Black Canadians (seasonal laborers and farmers for men, domestic workers and laundresses for women, for example) put their racialized communities at risk. When people are viewed as expendable and invisible, their exposure to environmental harm is of little consequence.

What might Francis’s story unveil for us about the experience of Black Canadians in 1918?

Francis might have known about the Coloured Women’s Club of Montreal (CWCM), which was founded in 1902, and worked with it. To assist with the flu epidemic, the CWCM kept a bed at Grace Dart Hospital and cared for the homes and children of hospitalized parents. The club members volunteered its members as visiting nurses and nurses’ aides. The CWCM also maintained a plot of land at the Mount Royal Cemetery for the internment of community members for those unable to afford the cost of burials.

Following his graduation, Francis travelled to Halifax to complete his certification before returning to the Caribbean. If he stopped in Sydney, he would have met Caribbean migrant workers.

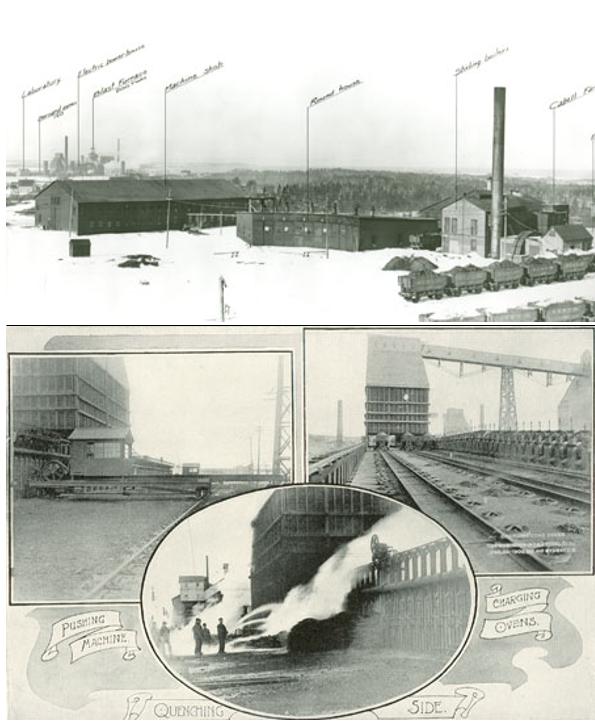

Panoramic view of the Sydney Mines in Nova Scotia with buildings like the furnaces labeled (top). Three images depicting the coke ovens at the Dominion Iron and Steel Company (bottom).

Desperate and in need of cheap and expendable labor, companies such as the Dominion Iron and Steel Company (DISCO) recruited Caribbean men to work in Sydney, Halifax. Based on the erroneous assumptions that Blacks could withstand the heat, Caribbean men were relegated to work in the mines, around the steel plant’s coke ovens, or blast furnaces.

Caribbean workers’ residences mirrored their employment. Had Francis visited any of the men’s homes, he would have noticed how close they lived to the plants. He might have heard the deafening noise emanating from the tar plant and coke ovens.

Members of Whitney Pier community would have complained to Francis about how the exposure to toxic pollutants impacted the health of the community. They would point to a disproportionate case of lung diseases, tuberculosis, pneumonia and pleurisy.

The No. 3 Colliery at the Dominion Coal Company, 1903.

Francis most likely would have returned home to the Caribbean and would have not heard about Beechville, a small Black community founded by Black refugees who fled to Canada after the War of 1812. The small community was ravaged by the flu. Thirteen people died in the pandemic’s opening weeks, and more would follow. One can only imagine the devastation and the heartbreak. How the disease was introduced to Beechville is unknown.

Despite the tragedy experienced by the community, none of Nova Scotia’s newspapers mentioned it. “Perhaps it was racism” was how the Nova Scotia Museum framed Beechville’s neglect, a typical Canadian response necessary to maintain its benevolent image.

Over one hundred years later and we are in the midst of another global pandemic. We should ask: what has changed for Black Canadians?

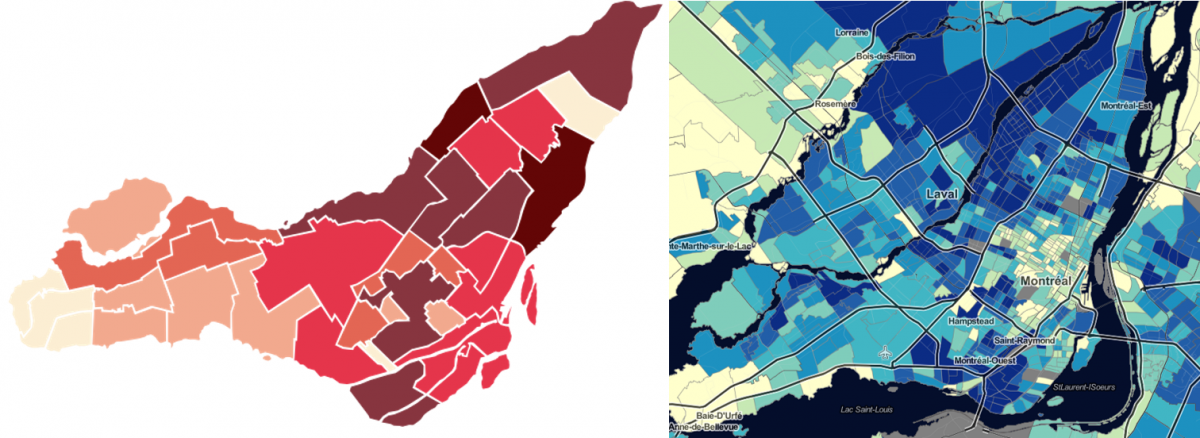

The density of COVID-19 cases in Montreal as of May 24, 2020 where the darker colors represent a high concentration of cases (left). The concentration of Black residents in Montreal as of 2016 according to Statistics Canada (right). The maps make clear the overlap between Black neighborhoods and incidence of COVID-19.

Whether in Toronto, Halifax, or Montreal, Black Canadians have been vocal about how their communities have been disproportionately impacted by COVID-19. Journalists, healthcare worker, scholars and community activists point to the racial and class dimensions of the disease.

Preliminary evidence reveals that race, income, education, and housing status determines who contracts COVID-19, similar to Beechville. The variables must also include a gender analysis. In Ontario, it is personal support workers, primarily Black and Filipina women who were the first to die from COVID-19.

While much has changed in terms of media coverage and the current pandemic, what has remained virtually the same are the structural forces that relegate Black people to living conditions that affects their health and well-being; conditions that motivated Oliver Michael Francis to work with the “coloured inhabitants of Montreal.”