In the wake of Donald Trump’s failure to immediately condemn the Ku Klux Klan and neo-Nazis following the events in Charlottesville, VA by condemning violence “on both sides,” he repeated a long history of blaming others for acts of terror perpetrated by white supremacists. To put Charlottesville in context, let’s review the history of white supremacist violence in the United States.

Although not the only white terrorist organization—there are an estimated 917 hate groups currently active in the U.S.—the Ku Klux Klan holds an iconic place in America. The Klan, formed immediately after the Civil War, began as a means to undermine former slaves’ freedom through acts of racial terror and intimidation. It declined during the late 19th century, but its ideas lingered on in the Jim Crow system of discrimination. The modern Klan re-emerged in 1915 at Stone Mountain, GA and grew into a national organization in the 1920s. During the Civil Rights Movement, the Klan bombed activists’ homes and churches and murdered those sympathetic to civil rights. Klan activity waned in the 1970s but the events in Charlottesville remind us that they have not gone away.

1. Fort Pillow Massacre, April 12, 1864

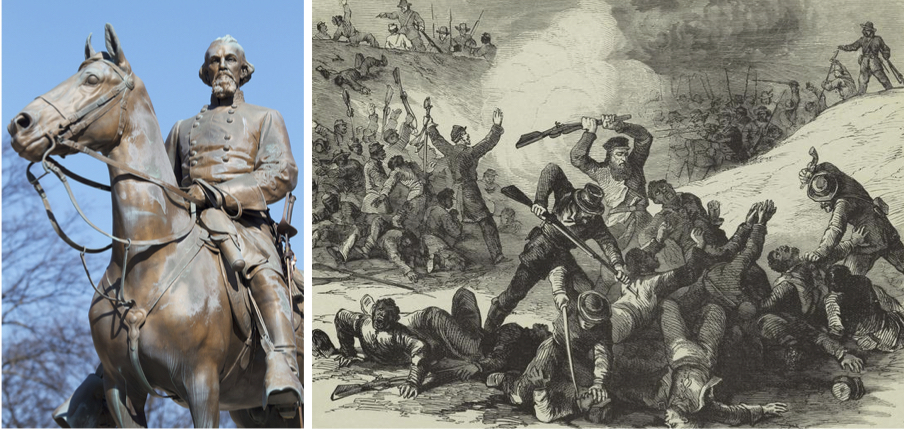

A statue of Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest in Memphis, Tennessee built in 1901 and still standing today despite a city counsel vote to remove it in 2016 (left). An 1864 depiction of the Fort Pillow Massacre in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (right).

In response to the Union Army’s enlistment of black men, Confederate President Jefferson Davis promised to execute captured black troops as slave insurrectionists. White Union troops were to be taken as prisoners of war, but black ones were to be killed or enslaved. At the Battle of Fort Pillow in Tennessee, Confederates under the command of General Nathan Bedford Forrest fulfilled this order when they slaughtered an estimated 300 surrendering black soldiers, some even as they lay wounded in hospital tents. Two dozen others were castrated.

Although far from the only atrocity against black troops during the war, it became a rallying cry for black soldiers to “Remember Fort Pillow!” After the war, General Forrest spent his remaining years denying that a massacre had occurred—he insisted that there had been no surrender—while also founding a soon-to-be well-known white terrorist organization, the Ku Klux Klan.

2. New Orleans Massacre, July 30, 1866

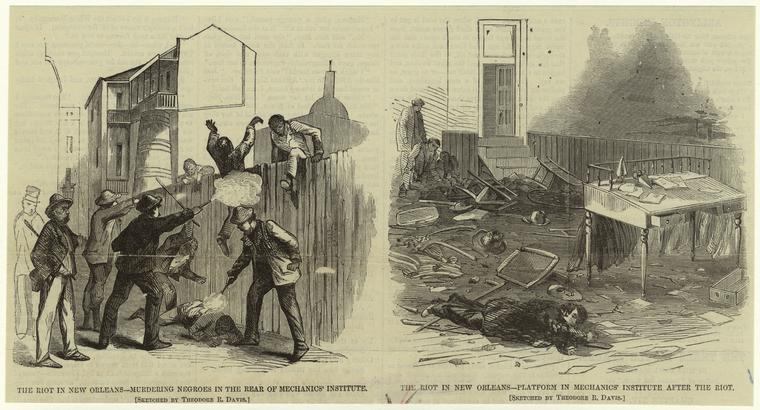

In 1866, at the Louisiana Constitutional Convention, ex-Confederates led by the Mayor of New Orleans opened fire on a parade of 130 black men celebrating the convention before attacking those in the convention hall. By the time they ran out of ammunition, 238 were dead, the majority of whom were black Union veterans or delegates. Federal troops arrived too late to stop the violence and although the mayor lost his office, no one faced charges for the massacre.

The attackers blamed black paraders for inciting the violence, but the mass shooting was a clear attempt to prevent expanding voting rights as the convention met to reverse the legislature’s refusal to enfranchise black men. Coming just two months after a massacre in Memphis, TN, the violence backfired as it aided the Republican Party in Congressional elections that fall, which led to federal occupation of the South and measures to allow black voting rights.

3. Colfax Massacre, April 13, 1873

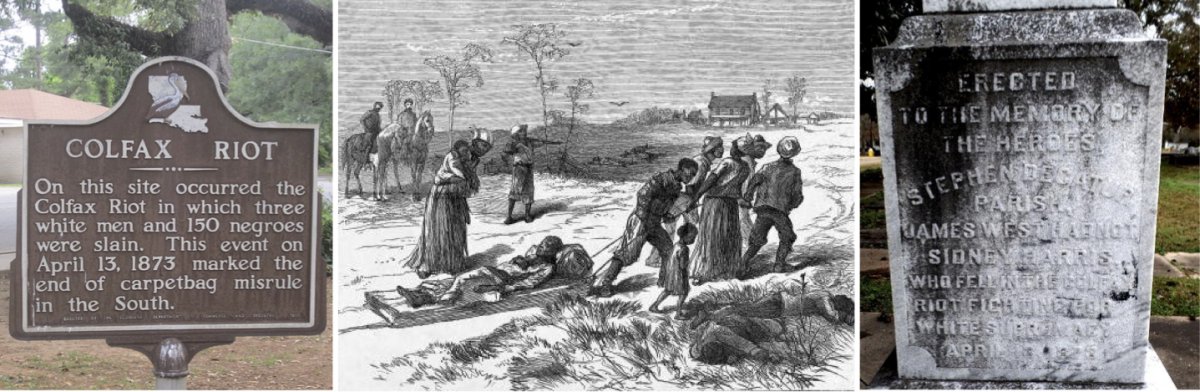

A historical plaque erected in 1950 calling the Colfax Massacre a riot and placing the blame on northerners (left). An 1873 depiction of the aftermath of the Colfax Massacre published in Harper’s Weekly showing survivors gathering the dead and wounded (middle). The inscription of a memorial built in 1921 to honor the three white men who died “fighting for white supremacy” (right). Both the plaque and monument are still standing in Colfax.

After a contested election in Louisiana, armed, white Democrats and ex-Confederates overpowered black Republicans who were protecting a courthouse from Democratic seizure. Both sides were armed but the black defenders proved no match against the white attackers’ numbers and armaments. Waving white flags, the black defenders surrendered, but were nevertheless mowed down after laying down their weapons. An estimated 153 black men were killed. Far from a mere dispute over an election, one of the attack’s leaders made the aim clear: “Boys, this is a struggle for white supremacy.”

While being one of the worst instances of racial violence during Reconstruction, its legal ramifications proved far more enduring. The federal government sought to punish the killers, but the resulting Supreme Court case, United States v. Cruikshank (1876), stripped its power to protect black Americans from racial violence as the court ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment did not apply to individuals’ actions, only state ones.

4. Wilmington Insurrection, November 10, 1898

Before the violence started, black voters were a numerical majority in Wilmington, NC. By the end, they were a minority. In local elections two days before the violent coup d’état, biracial coalitions elected a white Republican mayor and a biracial city council while white Democrats won the rest of the state. Furious at the election results in Wilmington, a white supremacist and former Confederate, Alfred Moore Waddell, led 2,000 insurrectionists against the city’s legitimately elected officials, attacked black homes and businesses, and installed himself as mayor.

An editorial in the city’s black-owned newspaper suggesting that some white women sought sexual relationships with black men—a taboo topic—supposedly justified the attack. The insurrectionists torched the newspaper and killed roughly 60 black Wilmingtonians. Over 2,100 African-Americans left the city during the carnage and did not return. North Carolina subsequently disenfranchised its black population.

5. Red Summer, May 10-October 1, 1919

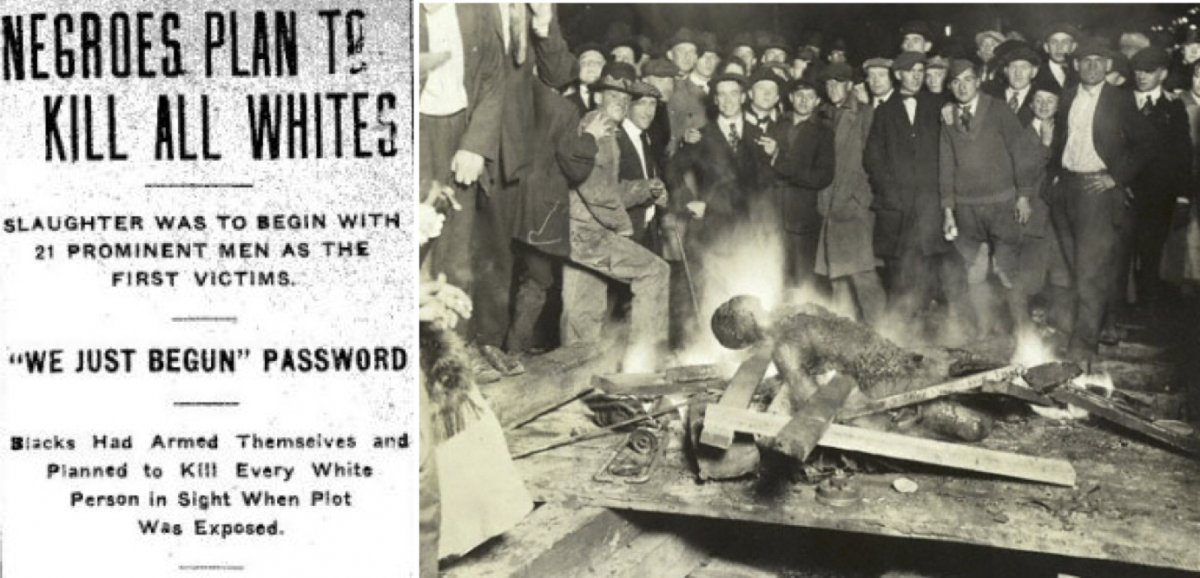

An inflammatory newspaper headline meant to justify the recent mass violence against African-Americans in Elaine, Arkansas in 1919 by suggesting that the black population had planned an uprising (left). A white mob poses with the body of a lynched African-American in Omaha, Nebraska in September 1919 (right).

As America demobilized from World War I, whites frustrated by job and housing shortages rioted in over three dozen cities during the summer of 1919, killing hundreds and injuring thousands of African-Americans. White mobs initiated every attack, but the press blamed Bolshevist agitation while others faulted the “attitude” of returning black soldiers.

The worst violence occurred in Elaine, AR when black sharecroppers gathered to unionize. White planters tried to disperse the unionizers but were met by armed resistance. After exchanging fire, the sheriff died. Subsequently, hundreds of armed whites converged to attack and kill the black population indiscriminately. When federal troops arrived, they detained hundreds of black people until white employers vouched for them. In the end, 122 blacks and no whites were charged with crimes. Twelve black men were executed for murder (5 whites had been killed) while the murders of over 237 black men, women, and children went unpunished.

6. Tulsa Race Riot, May 31-June 1, 1921

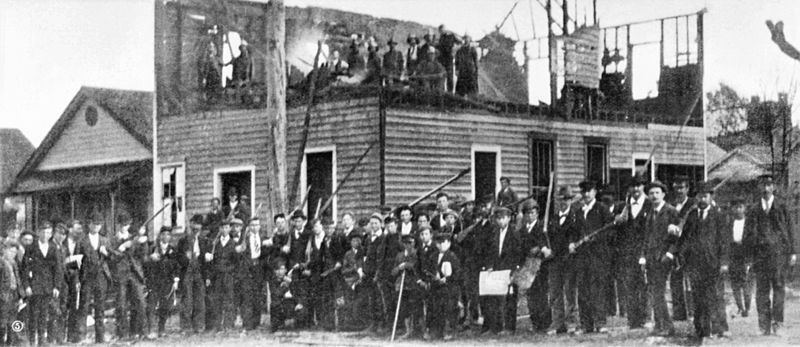

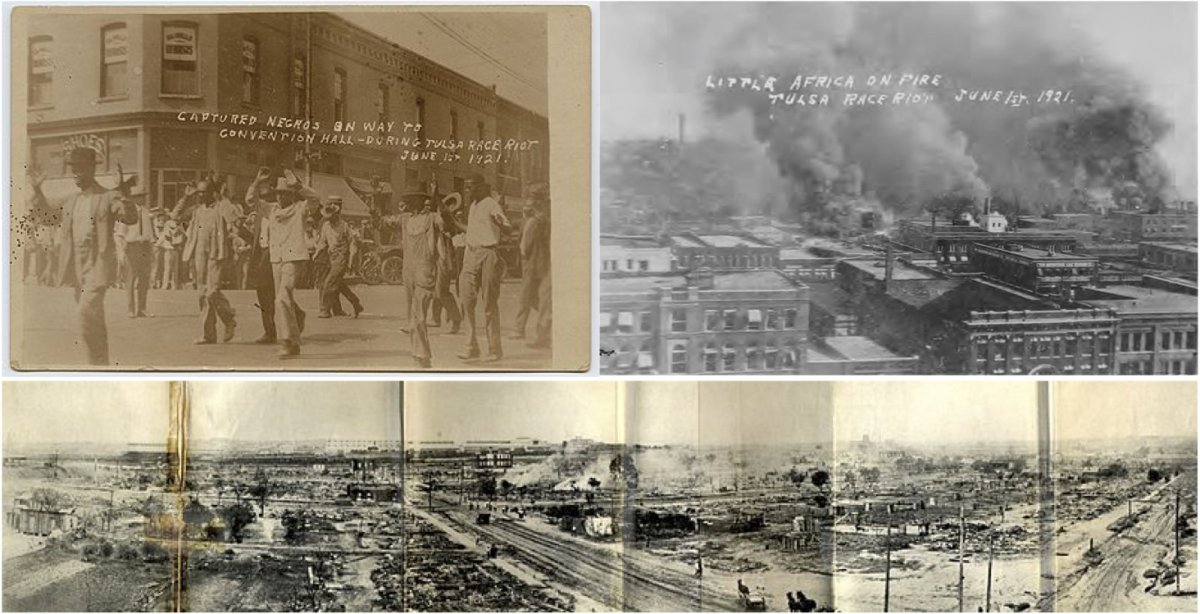

Black residents of Tulsa, Oklahoma were rounded up and imprisoned during the riot in 1921 (left). The black section of Tulsa, disparagingly nicknamed “Little Africa” but called Greenwood by its residents, ablaze during the riot (right). A panoramic photograph showing the extent of the damage to Greenwood after the riot (bottom).

For 14 hours in 1921, mass violence engulfed Tulsa, OK. White rioters killed around 300 black Tulsans, injured hundreds, and leveled the black section of town—Greenwood. The riot began after thousands gathered to lynch a black teen suspected of assaulting a white teen. When a small contingent of armed black men tried to prevent the lynching, the white mob began looting and shooting wildly as rumors of a “Negro uprising” spread. The police and hastily deputized recruits rounded up thousands of black Tulsans into detention centers while white vigilantes set Greenwood ablaze—even using planes to bomb the area.

Afterwards, a grand jury faulted the black men who prevented the lynching for inciting the riot. Those wanting to rebuild the once-prosperous Greenwood—which had been nicknamed “the Black Wall Street”—were unable as new fire codes made rebuilding all-but impossible. The next year, 1,700 Klansmen marched through Tulsa and won election to most local offices.

7. Ku Klux Klan “KonKlave,” August 9, 1925

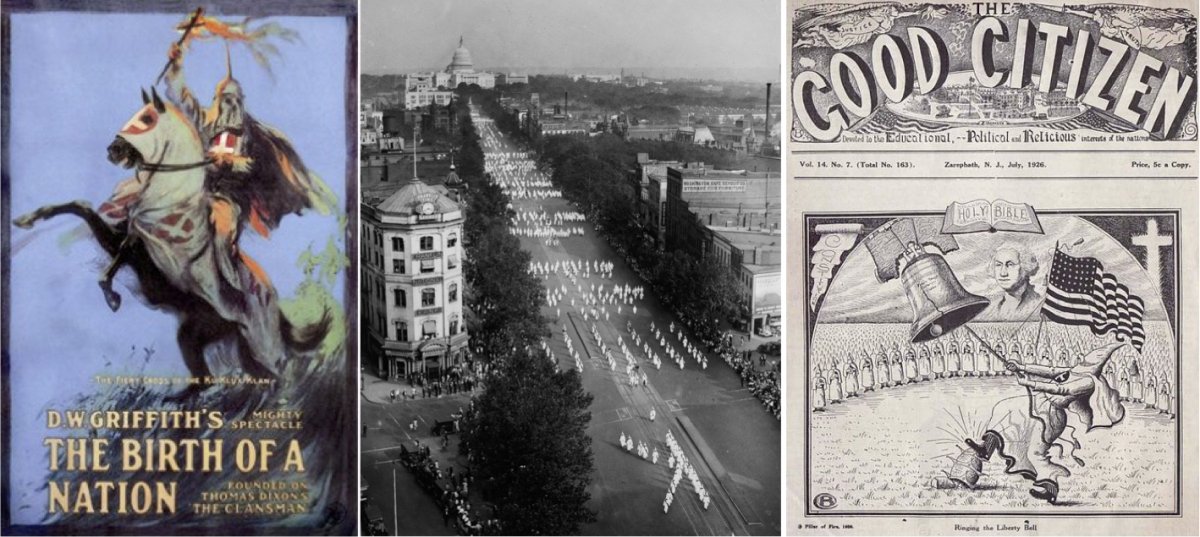

The movie poster for D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915), a film that glorified the Ku Klux Klan and vilified African-Americans (left). An aerial view of the Ku Klux Klan’s 1925 march in Washington, D.C. (middle). The 1926 issue of The Good Citizen, an anti-Catholic magazine and staunch supporter of the Klan, depicting Klan members surrounded by the trappings of patriotism and Christianity while one member stomps a Catholic priest into the ground (right).

In 1925, 30,000 Klan members marched down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C. Klan membership soared in the 1920s after the release of Birth of a Nation (1915) and amid immigration fears. Expanding its hate to Jews and Catholics, the 1920s Klan held a more prominent and national role than its earlier iteration. In marches like this, its brand of nativism, bigotry, intimidation, and extralegal violence were shrouded in patriotism. Women and children attended the march too, giving the event a picnic atmosphere.

Although no one died in the ostensibly peaceful demonstration, the march itself was a show of force with a clear message to the nation’s non-white, non-Protestant population—as was the 80-foot cross they lit that night. Marching confidently with hoods raised, Klan members acted with impunity. Despite hundreds of acts of violence annually, the Klan was a popular and respectable fraternal organization of white terrorists in the 1920s and beyond who scapegoated Catholics, Jews, and African-Americans.

8. 16th Street Baptist Church Bombing, September 15, 1963

The damage to the 16th Street Baptist Church by a Ku Klux Klan bombing in 1963 (left). The four young girls killed in the bombing were in the church’s basement changing into choir robes. Clockwise from top left: Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson, and Denise McNair (right).

Two weeks after Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, Klan members bombed an Alabama church with 200 worshipers inside. Killing 4 children and injuring 22 others, the bomb was the fourth in Birmingham in as many weeks in a city nicknamed “Bombingham.” Fed up, black residents protested that night, but were met only with violence.

The police shot one black teenager in the back while two white youths leaving an anti-integration rally killed another black teen.

Neither the police nor the two white youths faced consequences. The history of framing white supremacist violence as justifiable acts of self-defense set the stage for excusing these killings. No one was charged in the attack until 1977 when one Klansman was convicted for the bombing. Two others were convicted in 2001 and 2002, while the fourth perpetrator died without ever being charged.

9. Greensboro Massacre, November 3, 1979

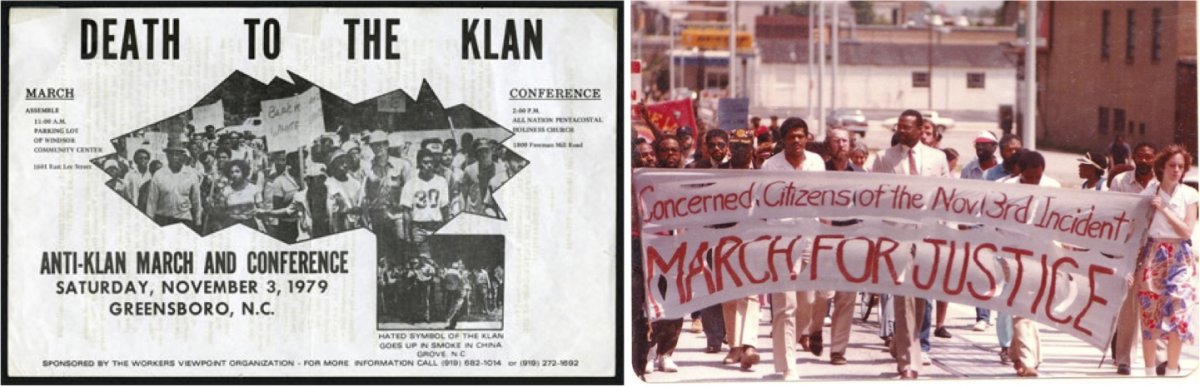

A flyer advertising the “Death to the Klan” march in November 1979 (left). A March for Justice following the Greensboro Massacre (right).

A 1979 anti-Klan rally in Greensboro, NC turned violent when 40 members of the Klan and American Nazi Party arrived with guns and fired into the crowd after the anti-Klan protestors pelted their vehicles with rocks. Klansmen killed 5 and wounded nearly a dozen others. The organizers of the anti-Klan march had openly called for the Klan to be “beaten and chased out of town” as “this is the only language they understand,” but were unprepared for the ensuing violence.

Despite being filmed by a local TV news crew, the 5 Klansmen charged with murder were acquitted by an all-white jury with the claim of self-defense. In 2009, the Greensboro City Council passed a resolution of regret for the murders and acknowledged its culpability in it as a police officer had given the Klan a map of the march route and was one of the 40 Klan members present.

10. Overland Park Jewish Community Center Shooting, April 13, 2014

Frazier Glenn Miller, a former Ku Klux Klan member convicted of murdering three people in 2014, published a racist tirade against Jews and “Negroes” in 1999 (left). The Overland Park Jewish Community Center the year before Miller’s 2014 shooting spree (right).

Klan members and other hate groups have long disparaged Jewish Americans, but the 2014 shooting at a Jewish community center in Kansas by an elderly former Army Green Beret, Klansman, and neo-Nazi shocked the nation. Frazier Glenn Miller killed three people, including a 14-year-old boy, in an attempt to kill as many Jews as he could. Miller failed, however, as his three victims were Christians. Miller had a long history of anti-Semitism, insisting that white people needed protection from Jews. Unlike many other white supremacist killings, Miller received a death sentence for his crimes. Upon conviction, he yelled “Sieg Heil” and gave the Nazi salute.

Had he been held accountable for earlier white supremacist activities, however, he might not have been able to carry out his shooting spree. A member of the National Socialist Party of America, Miller attended the Greensboro Massacre thirty-five years earlier.

This list is far from inclusive or even a ranking of the largest casualties from white supremacist violence but instead merely a sampling of some of the many instances of violence.