In some ways, the feminist movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries culminated with the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution that finally gave American women the right to vote. Many feminists in the 1960s and 1970s felt that adding the Equal Rights Amendment would be the next step in the movement for women’s equality. So far, the ERA has failed to win passage, though it came close. This month, historian Kimberly Hamlin examines the remarkable story of the ERA to look at who supported it, who opposed it, and how those coalitions shifted across the 20th century. She reminds us why the ERA movement remains as vital today as it was over the last century.

On March 22, 2017, Nevada became the 36th state and the first state in 40 years to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA).

Proponents believe this surprise victory signals that the ERA has a renewed chance to become the 28th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. To be adopted, amendments must be approved by Congress and then sent to the states for ratification by a two-thirds majority, or 38 states. With Nevada’s recent vote, the ERA now needs the approval of just two more. All eyes are on Illinois and Virginia.

Groups such as the ERA Coalition are organizing federal and state-based ratification efforts as well as building popular momentum through screenings of the 2016 documentary “Equal Means Equal.” There is a procedural hurdle, however, that may or may not be cleared: Congress set a 10-year time limit for state ratifications, which technically expired in 1982, placing the existing state approvals in legal limbo.

A protestor’s sign at the Women’s March in Washington, D.C. in 2017.

Forty-five years after Congress approved it, might the ERA become the 28th Amendment to the Constitution? And, if so, what would that mean for American women and men?

The success or failure of the ERA hinges on what “equality” means for women and on the extent to which equality can be legislated. Historically, the ERA has struggled to sustain consensus support among women because, unlike the vote (the 19th Amendment was ratified in 1920), it has not always been clear that the ERA would benefit all women since women’s needs vary according to their professional and marital status, as well as their race, class, and sexual orientation.

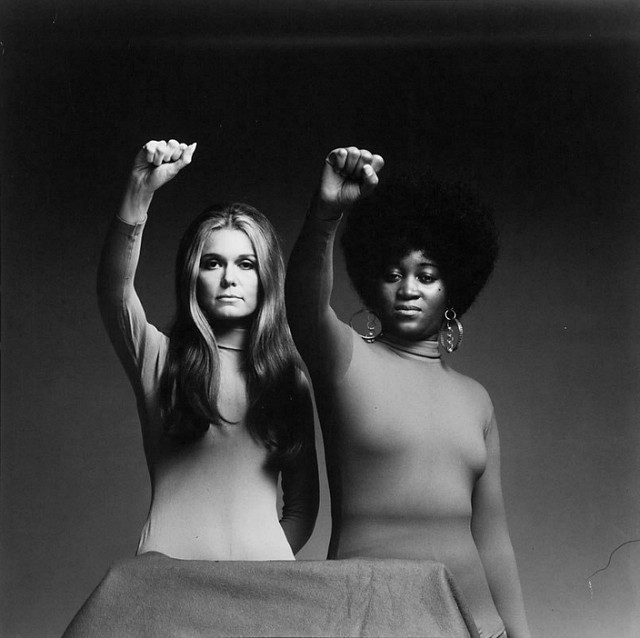

At the outset, the ERA was envisioned as a way to remove barriers for educated and professional women. Since its revival in the 1960s, the ERA has served as shorthand for a larger feminist agenda that promotes, as the bumper sticker says, the radical notion that women are people.

A t-shirt worn by a supporter of the Equal Rights Amendment in the 1980s now being worn by the supporter’s daughter (left). A protester in San Francisco during the Women’s March in 2017 calling for the immediate ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment (right).

When the ERA is described in terms of equal pay for equal work, Americans tend to support it. However, when it is understood as a tool to eradicate gender-based distinctions in public and private life, including those governing who changes the diapers and prepares dinner, support withers.

This creates a conundrum. If cultural norms surrounding motherhood create the conditions of female inequality, can equality be attained legally without changing traditional gender norms and expectations?

The Origins of the Equal Rights Amendment

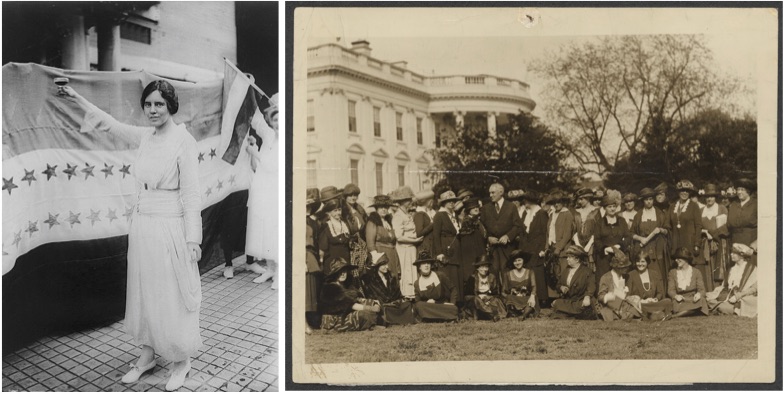

First introduced by Alice Paul in 1923, the ERA aimed to overturn the many forms of sex discrimination that persisted after women attained the vote in 1920. Paul and her allies in the National Woman’s Party (NWP) pointed out that more than 1,000 state laws discriminated against women, including those barring women from serving on juries, attending graduate schools, holding many jobs, and controlling their own bank accounts.

Rather than fight these individual laws one by one, the NWP hoped to overturn them all with one federal amendment. The original text of the ERA, written by Paul, read simply: “Men and women shall have equal rights throughout the United States and every place subject to its jurisdiction.”

Alice Paul, the author of the original Equal Rights Amendment, in 1920 (left). Fifty members of the National Woman’s Party meeting with President Warren G. Harding at the White House in 1921 to urge him to support the Equal Rights Amendment (right).

The goal of the ERA was to erase sex as a basis of legal classification, but the vast majority of activist women (together with the vast majority of Americans) rejected this line of thinking. Opponents argued that women were different from men and, as such, needed legal protection, not legal equality.

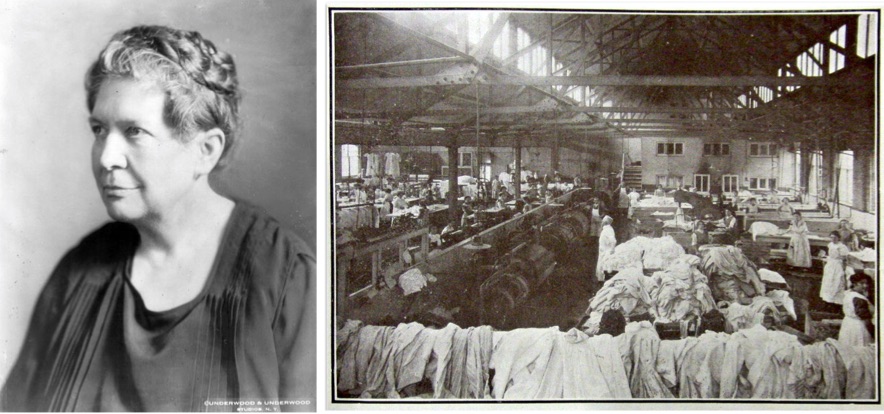

Women’s groups, labor unions, and others representing female factory workers had long pushed for protective legislation to spare women from the worst industrial ills of the era, such as unregulated hours on the job, dangerous working conditions, and physical tasks too arduous for pregnant bodies.

In the years leading up to the introduction of the ERA, the Supreme Court endorsed workplace protections for women only in the case of Muller v. Oregon (1908). In 1905, Curt Muller, a laundry owner from Portland, was arrested for violating the state law prohibiting women from working more than 10 hours per day. He appealed his conviction all the way to the Supreme Court, arguing, “It is time we ceased to classify women, in general, with children, criminals, and idiots. They are citizens, and their privileges and immunities may not thus be abridged by legislative majority.”

Florence Kelley, the powerful leader of the National Consumers League (NCL), disagreed. She enlisted future Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis to argue the case in favor of the Oregon 10-hour workday for women. In his brief, Brandeis advanced the idea that special protective laws for women were necessary because “facts of common knowledge” establish that “overwork is more disastrous to the health of women than of men” because of “women’s special physical organization.” For women, overwork could impair “childbirth and female functions.”

Florence Kelley, the head of the National Consumers League, in 1925 (left). Conditions in commercial laundries at the turn of the century were difficult and dangerous (right).

The Supreme Court voted unanimously to uphold the Oregon law. Writing for the Court, Justice David J. Brewer expounded on the juridical and political necessity of separate laws for women because “as healthy mothers are essential for vigorous offspring, the physical well-being of women becomes an object of public interest and care in order to preserve the strength of the race.”

Brewer’s brief also set the legal precedent that women should be considered “a class by herself,” rather than as a gender-neutral subject alongside men. After the Muller decision affirmed sex as “a valid basis for classification,” the majority of states enacted protective labor laws for women only and, despite the fact that many women did not have children, the courts considered all women mothers.

Throughout the 1920s, women debated what the ERA would mean for the legal protections secured under Muller v. Oregon. Opponents feared that the ERA would harm working-class women by invalidating gender-based workplace safety laws. Paul and her allies argued that the ERA would require safety laws that protected both men and women.

These debates divided and sapped the women’s movement. By the end of the decade, not a single state had passed an equal rights provision and, along with many other reform movements, the women’s movement lost momentum and supporters. The Supreme Court ruling that women should be “a class by herself” remained unchallenged.

National Woman’s Party delegates of New York lobbying Governor Al Smith for his support of the Equal Rights Amendment in 1924 (left). Envoys of the National Woman’s Party in Rapid City, South Dakota traveling to a meeting with President Calvin Coolidge to ask for his support of the Equal Rights Amendment in 1927 (right).

A New Deal for Women?

Throughout the Great Depression and World War II, women entered the workforce in record numbers but in increasingly sex-segregated jobs (for example, as secretaries). Business and professional women’s groups continued to endorse the ERA, but women in labor and politics remained opposed.

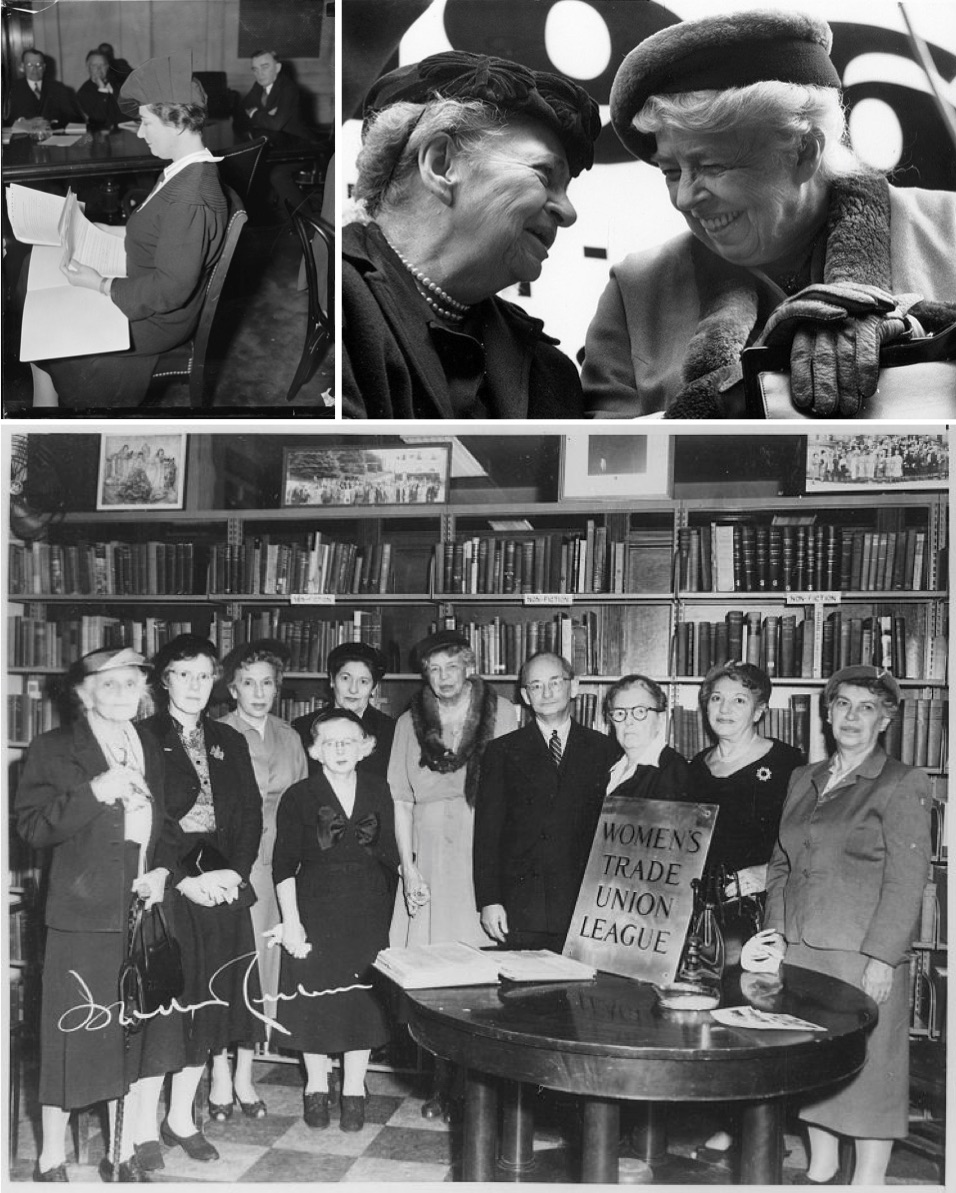

In the 1930s, New Deal legislation extended some protections to all workers, regardless of gender, in large part thanks to the efforts of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. An outspoken ERA opponent, Roosevelt helped draft early versions of New Deal proposals ensuring an eight-hour workday and collective bargaining for men and women alike. She supported equal pay for women but also gender-based protective legislation because the state “must concern itself with the health of the women because the future of the race depends on their ability to produce healthy offspring.”

“Women are different from men,” explained Roosevelt in her 1933 manifesto It’s Up to the Women. “They are equal in many ways but they cannot refuse to acknowledge their differences.”

Dorothy Straus, a New York attorney, testifying before the Senate Judiciary Committee in 1938 against the ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment (left). Former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt with former Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins in 1961 at the fiftieth anniversary of the Triangle Fire—a fire in a garment factory that took the lives of over one hundred women and launched a movement for workplace safety regulations (right). Former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt with members of The Women’s Trade Union League in New York in 1958 (bottom).

In 1940, the Republican Party endorsed the ERA in its platform, and the Democratic Party followed suit in 1944. In 1943, Alice Paul rewrote the text of the Equal Rights Amendment and, notably, removed the word “women.” The revised (and current) text reads: “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.”

Despite vocal opposition from women’s groups, including the League of Women Voters, the American Association of University Women, and the Young Women’s Christian Association, the ERA first came to Senate floor in 1946. In a vote of 38 to 35, it achieved a simple majority but fell short of the necessary two-thirds required. Cheering the ERA’s first Senate defeat, the New York Times proclaimed, “Motherhood cannot be amended.”

The New Feminism and the New ERA

In 1960, after newly elected President John F. Kennedy failed to appoint any woman as a cabinet secretary, longtime female activists in the Democratic Party demanded inclusion. Specifically, they proposed the creation of a Commission on the Status of Women to be led by Eleanor Roosevelt. Esther Peterson, head of the Labor Department Women’s Bureau, supported both equal pay and protective legislation, and she hoped that the commission would “substitute constructive recommendations for the present troublesome and futile agitation about the equal rights amendment.”

On October 11, 1963, the 24-member commission submitted its proposals to “enable women to continue their roles as wives and mothers while making a maximum contribution to the world around them.” In particular, the report recommended the removal of legal barriers to jury service, divorce and custody law reform, and federal support for daycare. The report rejected the ERA on the grounds that women’s equality was already guaranteed by the 5th and 14th Amendments (which, ironically, is the amendment that introduced the word “male” into the Constitution).

The press and public paid little attention to the commission or its findings, but by the end of 1963, Congress passed the first Equal Pay Act and provided federal funds for daycare. By 1964, 32 states had formed their own commissions on women. Even though the Kennedy commission denied the need for the ERA, by the mid-1960s many labor groups and wage-earning women were coming to support it. As Eleanor Roosevelt explained, “[M]any of us opposed the amendment because it would do away with protection in the labor field. Now with unionization, there is no reason why you shouldn’t have it if you want it.”

At the time, ending racial segregation and discrimination was a much more pressing concern than promoting equal opportunity for women. But the two causes were (and remain) fundamentally intertwined because of the ways that race and gender intersect—for example, were African American women to be considered as women, or as African Americans?—and because of the ways anti-discrimination laws were written.

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was introduced to prohibit discrimination by race. At the last minute, Representative Howard W. Smith of Virginia, a longtime supporter of the ERA and an opponent of civil rights, inserted the word “sex” into an amendment. Some thought he did so to tank the bill, others saw it as an act of “southern chivalry to white women.” Smith’s amendment threw the fate of the Civil Rights Act into question. After much wrangling and thanks to the bipartisan support of the few women in Congress, the Civil Rights Act passed with the word “sex” included.

In one of the many ironies of ERA history, the Civil Rights Act designed to obviate the need for an ERA instead deepened it. Female civic leaders, including some who had opposed inserting “sex” into Title VII, were dismayed to find that the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, created to enforce the Civil Rights Act, investigated charges of racial discrimination much more actively than charges of sex discrimination. What was the point of having a law against sex discrimination if it was not enforced? Maybe women needed an Equal Rights Amendment after all.

Democratic Congressman Howard K. Smith of Virginia (left). President Lyndon Johnson signing the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (right).

In 1966, a new civil rights organization for women was founded to address the inequities highlighted by the uneven enforcement of the 1964 Civil Rights Act: the National Organization for Women (NOW). NOW revived the ERA in 1967, and the amendment appealed to a new generation of women in ways Alice Paul and earlier activists could not have imagined.

The women of Paul’s generation believed that a woman should be able to choose a career or a family, a radical notion at the time. A priority of “second wave” feminism was to dismantle the old idea that women’s roles were inherently maternal and to suggest that a woman could have both a career and a family. NOW, for example, rejected the notion that “mothers have a special child-care role that is not to be equally shared by fathers.” “Equal” provided the buzzword for the movement and, thus, the Equal Rights Amendment seemed a fitting, all-encompassing goal.

With workplace protections secured by legal precedent and strong labor unions, working-class white women now divided their support on equal rights. In many cases, it was union women who led the charge for equal pay and against workplace discrimination. They filed Title VII discrimination lawsuits and encouraged their unions to support the ERA. As one member of the Chemical Workers Union explained at a Congressional hearing: “We do not want separate little unequal unfair laws and separate little unequal low-paid jobs.”

Working-class housewives, however, viewed the ERA as a threat to their status and as an assault against their values. These women were not angling to break into the all-male fields they saw around them—coal miner, construction worker, auto manufacturer—and feared that stripping sex-based distinctions from the law would deprive them of spousal benefits, such as alimony and social security, provided to stay-at-home wives.

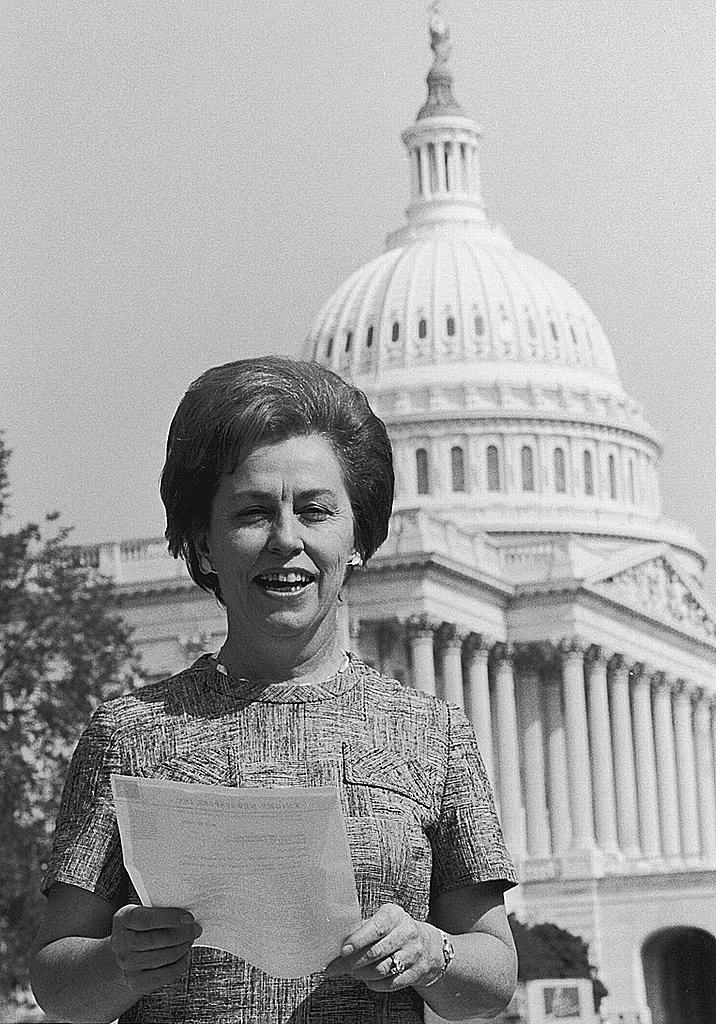

|

| Congresswoman Martha Griffiths, a Democrat from Michigan, resurrected the Equal Rights Amendment. |

The growing prominence of feminism in the early 1970s also helped to elect a handful of women to Congress and to convince both major political parties of the need for federal laws to ensure the equality of women. Representative Martha Griffiths, a former lawyer and judge from Missouri who had served in Congress since 1954, steered the ERA through Congress.

The ERA passed the House in 1970 and 1971 but stalled in the Senate as a result of attempts to add an amendment recusing women from the draft. Finally, on March 22, 1972, the Senate passed the ERA by a vote of 84-8. President Richard Nixon signaled his support and, by the end of 1973, 30 of the necessary 38 states had ratified.

In the early 1970s, equality for women appeared inevitable and public opinion polls repeatedly showed strong majority support for the ERA. Congress passed a host of laws guaranteeing equal access for female medical students, tax deductions for child-care expenses for working parents, and expanded pay equity, among many others. The courts also displayed a novel enthusiasm for equality by rejecting single-sex education, overturning workplace protections that applied only to women, and upholding sex discrimination lawsuits.

Popular culture, too, celebrated the equality of women in TV shows such as the iconic “Mary Tyler Moore Show” which ran from 1970-1977. Mary Roberts, the single protagonist, moved to Minneapolis after being dumped by her boyfriend and, in the series finale, a still single Mary declared to her work friends that she had finally found her family: “What is a family anyway? They’re just people who make you feel less alone and really loved. And that’s what you’ve done for me. Thank you for being my family.”

Mary Tyler Moore portraying Mary Richards, a professional woman in 1977 (left). First Lady Betty Ford crossing her fingers and wearing a button in support of ratifying the Equal Rights Amendment in 1975 (right).

Women’s Rights vs. Family Values

In 1973, however, the tide began to turn against the ERA. Historians have identified multiple factors to explain this shift—from well-organized Mormon opposition to the high-profile resistance from corporations such as Coors Brewing.

Feminist icon Gloria Steinem blamed the insurance lobby. Removing sex-based actuarial tables might have cost insurance companies millions of dollars. Requiring health insurers to fully cover women’s reproductive healthcare could cost untold more. Steinem quipped that “insurance agent” was the most popular profession among state legislators in the 1970s.

Gloria Steinem at a news conference for the Women’s Action Alliance in 1972 (left). A sign from the 2017 Women’s March quoting Eleanor Smeal, a former president of the National Organization for Women (right).

In addition to the insurance industry, Eleanor Smeal, current president of the Feminist Majority Foundation and past president of NOW, insisted that big business was to blame. “We’re the cheap labor pool,” explained Smeal. If an ERA were to be ratified, corporations would not only have to pay women more, they might also be subject to settlements for past wage and promotion discrimination.

All of these factors no doubt played a role in the failure of the ERA, but most people, historians and activists alike, agree that credit or blame, depending on whom you ask, belongs to Phyllis Schlafly and her STOP ERA campaign.

Between 1973 and her death in 2016, Schlafly tirelessly toured the country, goaded feminists, and appeared on countless TV and radio programs to derail the ERA. Even though she was a lawyer and political activist, she relished beginning her speeches by saying, “I’d like to thank my husband, Fred, for letting me be here today.”

Schlafly argued that the ERA would lead to women being drafted, gay marriage, and gender-neutral bathrooms. These fear-based tactics made for catchy buttons and posters, but the crux of her message was that the ERA would prevent women from being housewives. The “STOP” in STOP ERA stood for “Stop Taking Our Privileges.” As Schlafly explained, “Women want and need protection. Any male who is a man—or gentleman—will accept the responsibility of protecting women.”

Schlafly’s most effective strategy was to harness the various strains of ERA opposition, including conservative backlash after the Supreme Court legalized abortion in 1973, into one coherent narrative: God and nature intended for women, first and foremost, to be mothers; threats to this natural order were to be opposed.

Women opposed to the Equal Rights Amendment in Florida’s Senate chamber in 1979 (left). Anti-Equal Rights Amendment protesters in front of the White House in 1977 (right).

Looking back, the 1972 debate over the Comprehensive Child Development Bill foreshadowed the fate of the ERA. Even though Congress passed numerous equity laws in the early 1970s, President Nixon vetoed only the child development proposal that would have provided a national network of federally funded daycare centers. In his veto explanation, President Nixon rejected the “communal approach to child-rearing” and the “family-weakening implications” of the bill. As the editors of the New York Times wrote, “It’s fine for mother, but what about the child?”

Subsequent opposition to the ERA successfully elaborated the false logic that feminism forces a choice between women’s rights and family values. As Nevada Senator Becky Harris, the only female senator to vote against the ERA in 2017 explained, “An Equal Rights Amendment (without) exclusions to protect families and protect children is something I cannot support.” Are women people? Maybe. But mothers, as a cross between superhero and maidservant, are not.

The 24-Hour Woman

In 1977, Indiana became the last (until Nevada) state to ratify the ERA. In 1980, the Republican Party, reshaped by Schlafly and the “family values” movement, dropped support for the ERA from its platform. In 1982, the 10-year time limit for ratification of the ERA expired.

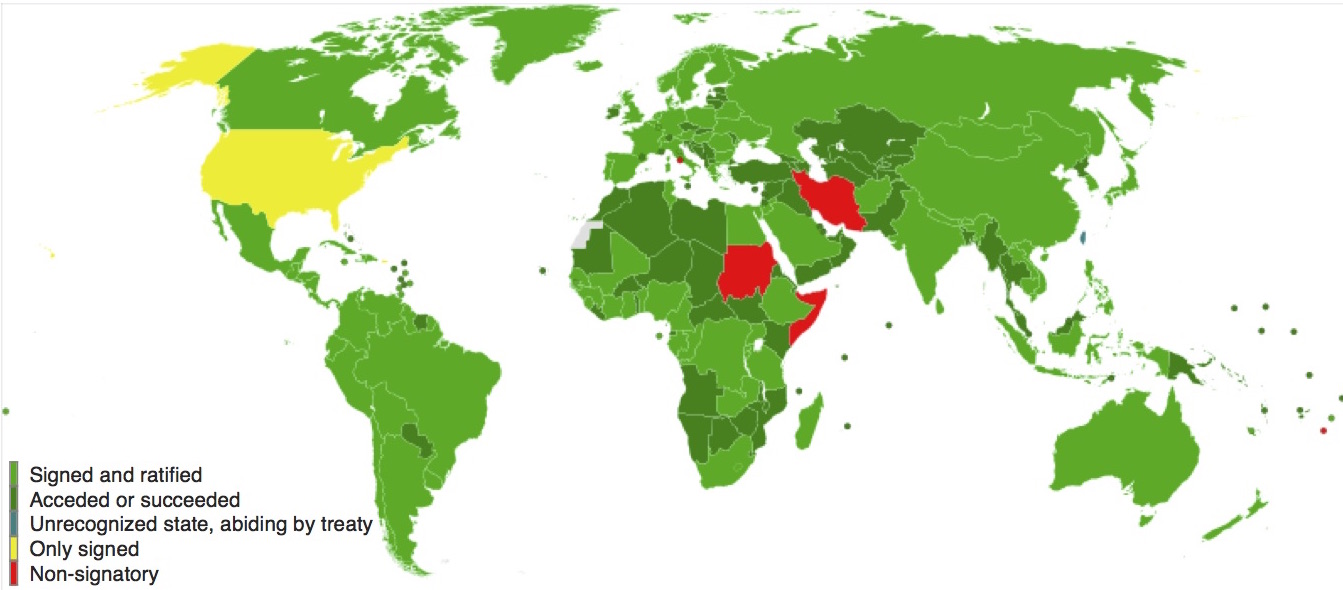

Since then, the U.S. has also steadfastly refused to join 187 other countries in ratifying the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women. Others who refuse are Sudan, South Sudan, Somalia, and Iran.

In the absence of a federal ERA, 22 states have passed their own version of an Equal Rights Amendment. And several separate federal proposals promoting the principles of the ERA have become law—including the Lilly Ledbetter Pay Act of 2009, the first bill signed into law by President Obama.

Over the past 45 years, many of the anxieties expressed by Schlafly’s STOP ERA campaign have come to pass anyway. On June 26, 2015 the Supreme Court ruled that same-sex marriages are legal in all 50 states. In December 2015, the Pentagon announced that women could serve on the front lines of combat (though women are not yet subject to the draft). And, despite vocal opposition in states such as North Carolina, gender-neutral bathrooms are becoming the norm in schools, work places, and public buildings.

At the same time, with middle-class wages stagnant and with marriage rates declining, Schlafly’s homemaker ideal is increasingly obscure. Indeed, the U.S. Census Bureau titled a recent report “The Single Life” and noted that a record 53% of women 18 and older are single, along with 47% of men.

None of these legal, political, and cultural shifts, however, have directly challenged the widespread conviction that women’s primary role is maternal or, put another way, that domestic and child-rearing tasks are best performed by women.

The overwhelming majority of Americans continue to profess support for women’s equality, and especially for equal pay, but we remain ambivalent about proposals that would turn the abstract principle of equality into concrete policies. Neither does support for the principle of equality signal that Americans are interested in fundamentally rethinking conventional gender roles. In other words, men agree that women are equal in theory, but men are not necessarily lining up to do more dishes and carpools.

The number of stay-at-home fathers has doubled since 1989, but only 21% (compared to 73% of stay-at-home moms) say that their primary reason for staying at home is to care for family. The majority are disabled, ill, or unable to find work. Recent studies indicate that women shoulder a larger share of the work to take care of elderly family members too.

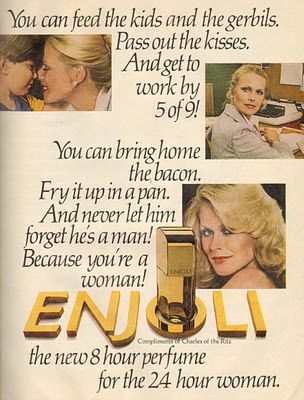

|

| A 1978 advertisement for Enjoli perfume in Vogue. |

Since the late 1970s, Americans have come to a tentative and tacit compromise with regard to women’s equality. Women can now enter any field (though some are notoriously more resistant to women than others) and work as hard as they are able … as long as they also still take care of the children (even if by arranging for childcare) and the home.

As the classic Enjoli perfume ad from 1978 extolled, women can “bring home the bacon, fry it up in a pan, and never let him forget he's a man.” The tagline for Enjoli, not incidentally, recommends it as “the 8-hour perfume for the 24-hour woman.” Social scientists now refer to this “24-hour woman” as the “second shift” phenomenon. After women work a full day at their jobs, they come home for a second shift of domestic labor (and, for many, another late-night shift of professional labor after getting the kids to bed). Many are back up at 5:30 am for boot camp or spin class because, like the Enjoli spokeswoman, women are also expected to remain youthful and beautiful as part of this bargain.

Even though it is now possible to see men doing laundry in detergent ads (and even to observe actual men performing actual housework in real homes), the fact remains that working women still do twice as much child care and housework as their male partners. Many commentators, including Sheryl Sandberg, Bridget Schulte, and Ann-Marie Slaughter, believe that this “second shift” accounts for the persistent glass ceiling in corporate boardrooms and in elective politics, even more so than structural barriers or gender discrimination. An even more recent study finds that “the gender pay gap is largely because of motherhood.”

Beyond the obvious time and stress constraints imposed by the “second shift,” the unspoken norm that women should do the grunt work of life extends from homes into workplaces. Who should prepare the office holiday party? Who should take the minutes at meetings? The same people who perform the unpaid and unacknowledged labor at home: women.

Would the ERA help eradicate these gendered norms? Maybe not, but history suggests that it is hard to attain equality in the absence of legislation.

Equality Begins at Home

With the election of President Trump, women’s rights activists are re-energized and growing in number as the January 2017 women’s march demonstrated. In fact, Nevada ERA proponents said they were motivated to revive the bill by Trump’s election.

NOW leaders hope that the Nevada vote will inspire ratification in both Illinois and Virginia, which would signal the necessary two-thirds approval, depending on how one counts and tells time. Senator Ben Cardin (D-MD) has proposed legislation that would extend the time clock so that the new state ratifications could join the 35 existing ones, but it is not clear if this could pass Congress. Further complicating the process, since 1982, a few states have rescinded their approvals.

Equal Rights Amendment activists in Nevada ahead of that state’s 2017 ratification (left). A woman celebrating Nevada’s passage of the Equal Rights Amendment and pledging that Virginia would do so next (right). Children at a Virginia rally supporting the Equal Rights Amendment in 2017 (bottom).

Another option would be to start state ratification all over again. If Congress did vote to remove the timeframe it initially imposed on ratification, then the Supreme Court would have to decide the next steps. Women’s rights activists are hopeful that, if nothing else, the latest interest in the ERA will spark discussion and perhaps even changes in individual homes and workplaces.

For nearly 100 years, the major sticking point in debates about the ERA has been whether women should be classified as mothers or as people. The courts, Congress, and to some extent the American people have repeatedly decided that women are not people deserving of equal rights; women are mothers, deserving of special rights.

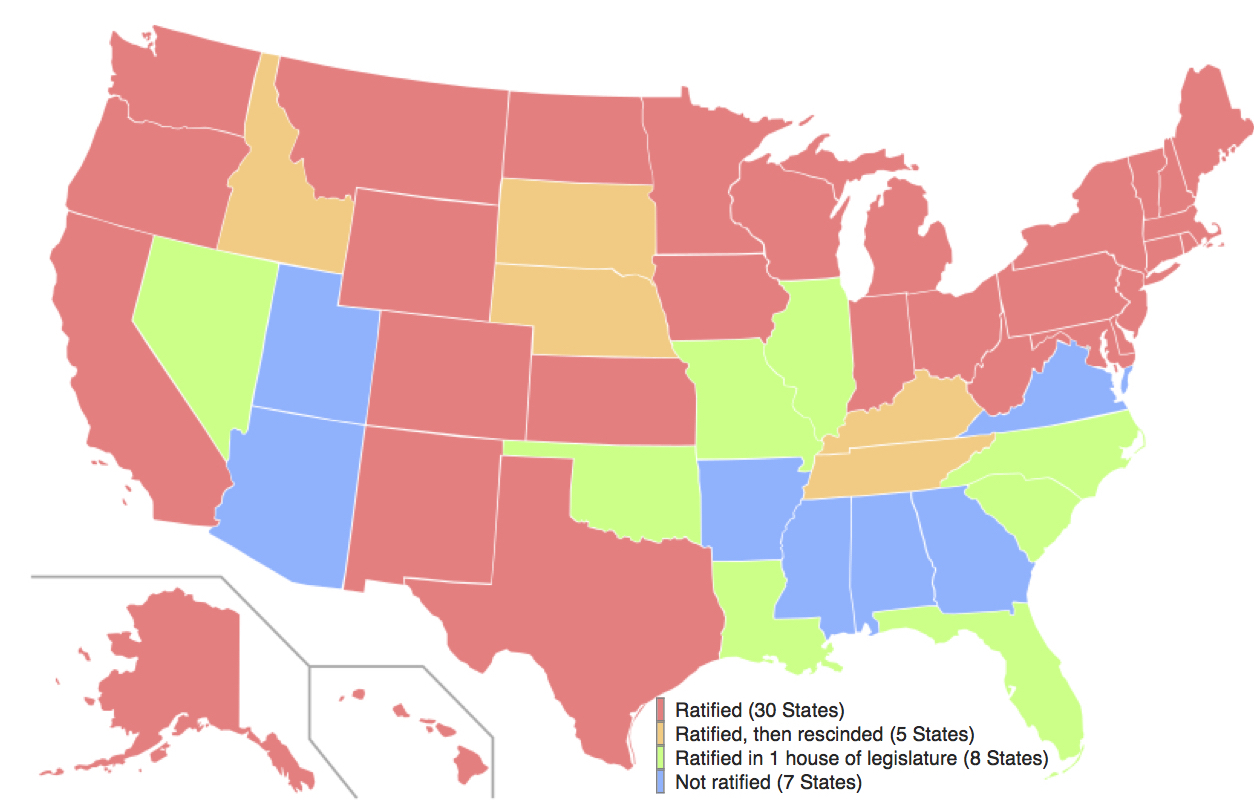

A map of the states that had ratified the Equal Rights Amendment as of 2007.

Whether or not the ERA ever becomes the 28th Amendment, there is some hope that one of its supposed consequences is already revolutionizing traditional gender roles within marriage and family life. Several recent studies have shown that same-sex marriages are much more egalitarian and, no surprise, happier than heterosexual marriages. By dismantling the idea that, naturally, the wife should perform the vast majority of childcare and housework, same-sex marriages provide a new model for marital partnerships and, perhaps, a path to equality for all.

If parenthood became prioritized over motherhood and if women, like men, were classified as people, rather than first and foremost as mothers, then many of the remaining barriers that women face would be removed, even in the absence of the ERA.

Demonstrators on the National Mall for the Women’s March in January 2017.

Listen more: The Equal Rights Amendment: Then and Now; Violence Against Women; Reproductive Rights and Reproductive Justice; Same-Sex Marriage; Abortion in Europe and America; and Women in the Mideast and North Africa

Read more: Women and American Politics; Domestic Violence; The Women’s March on Washington; Elizabeth Cady Stanton; The Real Marriage Revolution; Same-Sex Marriage; Women’s Struggles in Zimbabwe; Feminism in Egypt; and Women’s Rights in Afghanistan.

Check out a lesson plan based on this article: Are Women People?

Alice Paul Institute, “Equal Rights Amendment,” http://www.equalrightsamendment.org/

Berry, Mary Frances, Why ERA Failed: Politics, Women's Rights, and the Amending Process of the Constitution, Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1986.

Critchlow, Donald T., Phyllis Schlafly and Grassroots Conservatism: A Woman's Crusade, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005.

Critchlow, Donald T. and Cynthia L. Stachecki, “The Equal Rights Amendment Reconsidered: Politics, Policy, and Social Mobilization in a Democracy,” The Journal of Policy History, Vol. 20, No. 1 (2008), 157-176.

Davis, Martha, “The Equal Rights Amendment: Then and Now,” Columbia Journal of Gender and Law, Vol. 17.3 (2008), 419-459.

ERA Education Project, “Equal Means Equal,” http://eraeducationproject.com/what-is-the-equal-rights-amendment/

Feinberg, Renee, ed. The Equal Rights Amendment: An Annotated Bibliography of the Issues, 1976-1985, Bibliographies and Indexes in Women's Studies (Book 3), Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1986.

Hoff-Wilson, Joan, ed. Rights of Passage: The Past and Future of the ERA, for the Organization of American Historians, Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1986.

Mansbridge, Jane J. Why We Lost the ERA, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986.

Mathews, Donald G. and Jane Sherron De Hart, Sex, Gender, and the Politics of ERA: A State and the Nation, New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Neuwirth, Jessica, Equal Means Equal: Why the Time for an Equal Rights Amendment Is Now, New York: The New Press, 2015.

National Organization for Women, “Chronology of the Equal Rights Amendment,” http://now.org/resource/chronology-of-the-equal-rights-amendment-1923-1996/

Representative Carolyn B. Maloney, “Equal Rights Amendment,” https://maloney.house.gov/issues/womens-issues/equal-rights-ammendment

Sklar, Kathryn Kish, “Who Won the Debate over the Equal Rights Amendment in the 1920s?” in Women and Social Movements in the United States, 1600-2000, Database, Binghamton, NY : State University of New York, 2000.

Spruill, Marjorie J. Divided We Stand: The Battle over Women's Rights and Family Values that Polarized American Politics, New York: Bloomsbury, 2017.

Taylor, Paul and Philip G. Kiko, “The Lost Legislative History of the Equal Rights Amendment: Lessons from the Unpublished 1983 Markup by the House Judiciary Committee,” University of Maryland Law Journal of Race, Religion, Gender, and Class, vol. 7.2 (2007): 341-374.

Woloch, Nancy, A Class by Herself: Protective Laws for Women Workers, 1890s–1990s, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015.

Woloch, Nancy, Women and the American Experience, 5th edition, New York: McGraw-Hill Education, 2011.

Young, Neil J., “ ‘The ERA is a Moral Issue’: The Mormon Church, LDS Women, and the Defeat of the Equal Rights Amendment,” American Quarterly vol. 59, no. 3 (2007), 623-644.

Zahniser, J. D. and Amelia R. Fry, Alice Paul: Claiming Power, New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.