The 1998 "Good Friday Agreement" was a breakthrough in the Northern Ireland peace process. Holding for nearly 20 years, it has brought a measure of stability and tranquility to an area wracked by Protestant-Catholic violence for decades. But as historian Jeffrey Lewis observes, the Good Friday Agreement only treated the symptoms of the conflict and did not redress its underlying causes. Examining the history of the sectarian divisions in Northern Ireland, he asks whether treating symptoms is sufficient to bring a lasting peace.

Read these insightful Origins articles for more on Europe: The Migration Crisis in Europe; The Ukrainian Crisis; European Disunion; Socialism in France; and Scotland and the United Kingdom

Listen to these History Talk podcasts on Road to Europe: The 2015 Migration Crisis; 1989: The Year That Changed It All; The Fate of Crimea; Memories of the Great War; and Armenians, Turks, and the Genocide Question.

On June 27, 2012, Queen Elizabeth II of England briefly met with Martin McGuiness, Deputy First Minister of Northern Ireland while touring Belfast as part of her Diamond Jubilee celebration. McGuiness shook the Queen’s hand and wished her well.

In most cases such an event—a symbolic meeting between the head of the Royal Family and a democratically elected public servant—would not be particularly noteworthy. However, this was not most cases, as McGuiness was not just any public servant.

|

Before making the turn to politics, McGuiness was a leader of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA), the terrorist organization responsible for more than 1,800 deaths and thousands of bombings in the United Kingdom (UK) between 1969 and 1998. The IRA’s violence was not only brutal and systematic, but from Elizabeth’s perspective it must also have been personal. In 1979, the organization killed the Queen’s cousin, Lord Mountbatten.

The meeting between the two and attendant photo op was thus a carefully stage-managed bit of political theater. It was also an appropriate representation of a peace process that, 17 years after its inception, remains stubbornly incomplete.

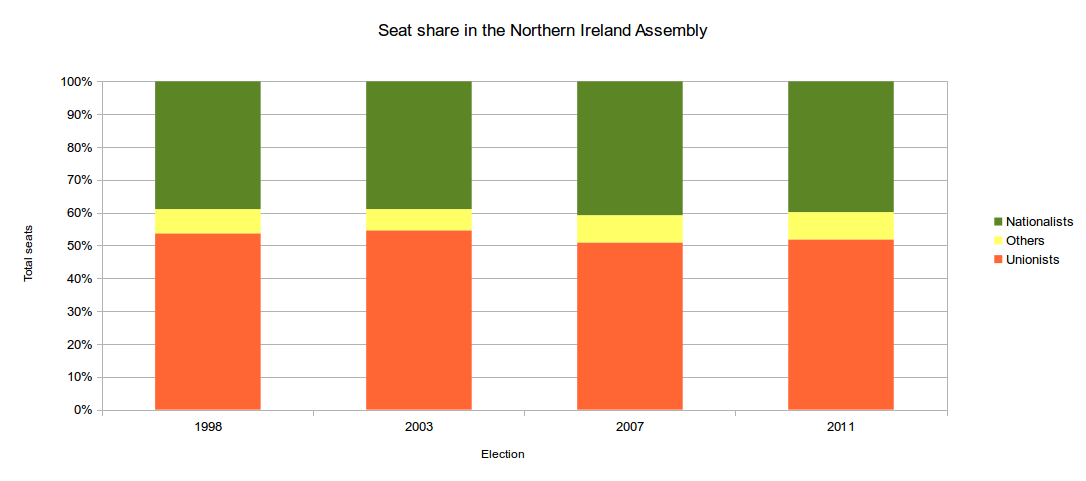

On the positive side, the Belfast Agreement (commonly referred to as the Good Friday agreement as it was first presented to the public on Good Friday, April 10, 1998) has produced a functioning government, one that effectively represents both of Northern Ireland’s political communities: Unionists (almost exclusively Protestant, who favor the ongoing inclusion of Northern Ireland in the UK), and nationalists (almost exclusively Catholic, favoring a closer relationship to, and in many cases integration into, the Republic of Ireland).

|

This power-sharing government has now persisted through multiple elections, changes of personnel and leadership, and a number of political scandals. Optimists point to this durability and suggest that the Belfast Agreement has been successful enough that it should be considered a model to other conflict-ridden societies.

At the same time, Northern Ireland remains one of the most divided societies in Europe. Catholics live in neighborhoods that are overwhelmingly Catholic, Protestants in neighborhoods that are overwhelmingly Protestant. Children from both communities are educated separately.

The geography of Belfast in particular remains partitioned rather than shared and the numerous “peace walls”—physical barriers separating the communities during the worst of the political violence—have not been torn down but have, in fact, increased in number in the years since the Good Friday agreement was signed.

|

According to a survey conducted in 2004, 84% of respondents indicated that they would not enter an area dominated by the other political community at night; 48% said that they would not enter such an area during the day, and a smaller percentage even indicated that they would forgo health care for themselves or younger members of their families rather than make use of health facilities in an area dominated by the other community.

The sectarian political violence has decreased dramatically but it has not disappeared—the resumption of terrorism is possible, albeit very unlikely.

In the years immediately after Good Friday, paramilitaries from both the Nationalist (usually referred to as “Republican”) and Unionist (“Loyalist”) communities continued to use violence to enforce their will among their own people rather than submitting to the rule of law.

|

Among Republicans this took the form of punishment beatings, knee-cappings, and even executions of nationalists deemed to have violated Republican codes of conduct. Loyalist paramilitaries, historically more poorly organized and disciplined, soon fell into gangsterism and turf wars.

How can one reconcile these two seemingly contradictory realities—a parliament that shares power representing a people that share very little? A medical metaphor might be appropriate: we need to draw a distinction between symptoms and causes.

From this perspective the Good Friday agreement was meant to alleviate the symptoms of the disease—widespread political violence—by integrating political elites into a common governing framework. The agreement has succeeded admirably in halting the violence, but curing the cause of the symptoms—a long history of sectarian mistrust—is a much more challenging proposition.

The agreement was meant to end a sectarian conflict and did so, at least at the political level, but did so by building sectarianism into the structure of the new government.

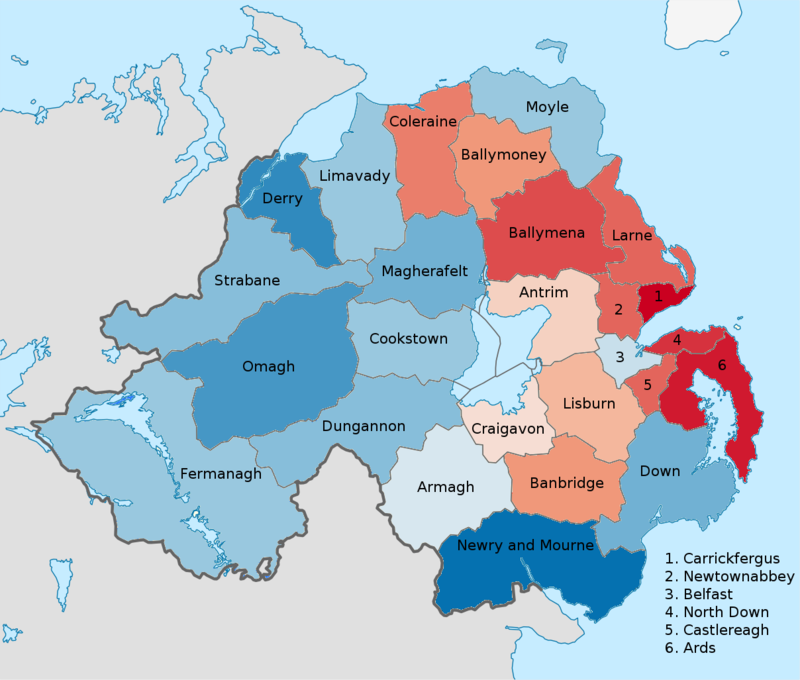

For example, members of the Northern Ireland Assembly created by the Agreement were required to register a designation of identity—nationalist, Unionist, or other—and these sectarian identities play a significant role in such crucial issues as election of the First Minister and Deputy First Minister.

The hope at the time was that stable political institutions, even if they were sectarian in nature, would allow for the return to normalcy that would be a necessary precondition for any deeper reconciliation.

The question today is whether treating the symptoms of the sectarian conflict has allowed the process of true healing to begin, or if it has simply masked a deeper disorder, a divided and suspicious political culture in which true reform is not possible.

British, not English: The Deep Roots of Conflict

The Unionists who exist today as a distinct community with a recognizable political agenda are a product of the history of British settlement on the island of Ireland.

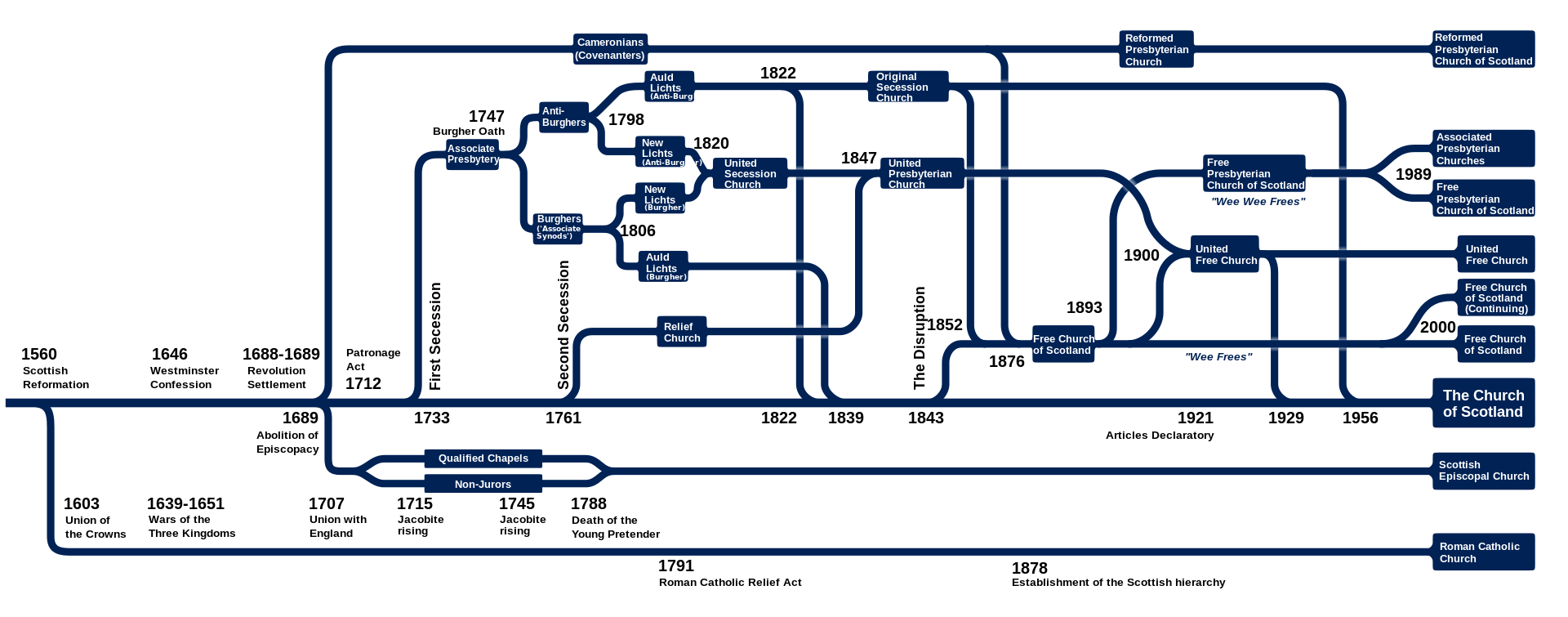

This colonial policy of migration, extant since the late 1200s, intensified in the late 1500s in the wake of the Protestant Reformation. As the English monarch Henry VIII broke with the Catholic Church and established the Church of England (or Anglican Church), most of the residents of Ireland chose to remain Catholic.

|

This division made choice of religion a de facto political position in Ireland, a situation that largely holds even today. Since England’s political foes, first Spain and later France, were Catholic monarchies, the Catholic Irish were viewed as potential traitors. The crown therefore sought to subjugate and control them, making the relationship between English and Irish inherently adversarial.

Through the 17th century English monarchs confiscated property from rebellious Catholics and created a set of laws that cemented the ascendancy of the Protestant minority in Ireland over the Catholic majority. Rules for land ownership were skewed in favor of Protestants and Catholics were denied the rights to vote and bear arms. The Test Act of 1704 required holders of public office to take communion in the Church of Ireland, the Irish extension of the Anglican Church, not the Catholic Church.

The result by the late 1700s was bitter hostility between a minority that controlled Ireland politically and economically and a majority that saw them as an illegitimate, alien presence.

As the Unionist community in Ireland put down roots and grew over the centuries, it developed its own collective identity differentiating it not only from Irish Catholics, but from the English government upon which it was utterly dependent. For example, most Unionists were the descendants of Scottish Presbyterians, not Anglicans, and thus acts such as the Test Act discriminated against them as well as against Catholics.

|

In the 20th century, the British government gave the Unionists further grounds for concern, first by supporting a Home Rule bill to establish a parliament in Dublin for the Irish people within the framework of the UK, then by creating an Irish state on the island in the aftermath of the struggle for Irish independence.

By this time, Unionists had created their own sense of British identity rooted in both their connection to England and their roots as “Scotch-Irish,” a unique combination of Scottish, English and Irish attributes.

“Ourselves Alone”

Irish nationalism emerged in the 19th century and was shaped by both positive and negative factors.

From the negative side, Irish nationalists defined themselves by what they were against—they were neither English nor British, and so their sense of collective political identity emerged in opposition to the Protestant ascendancy. From this perspective, British and Irish were two mutually exclusive categories.

As far as what they stood for, Irish nationalists defined themselves in terms of ideas unleashed first by the American Revolution and then more powerfully by the French Revolution. From both revolutions Irish nationalists were inspired by ideas of country and patriotism, and Irish nationalism came to be characterized by an appreciation of Gaelic history, culture, and language.

|

Politically, the Irish were inspired by the republican, anti-monarchical ideals of both revolutions. Since the Irish saw themselves as rebelling against a monarchy, they were naturally attracted to an alternative political system. Monarchy, after all, had offered them nothing but an inferior political, social, and economic condition, so Irish nationalism came to be characterized by a categorical rejection of the very idea of monarchy in favor of some form of republic.

For a great many Irish nationalists, the ideas of Ireland and a republic became all but synonymous—to be Irish was to be a republican and to be a republican was to be dedicated to the idea of an independent, united Ireland.

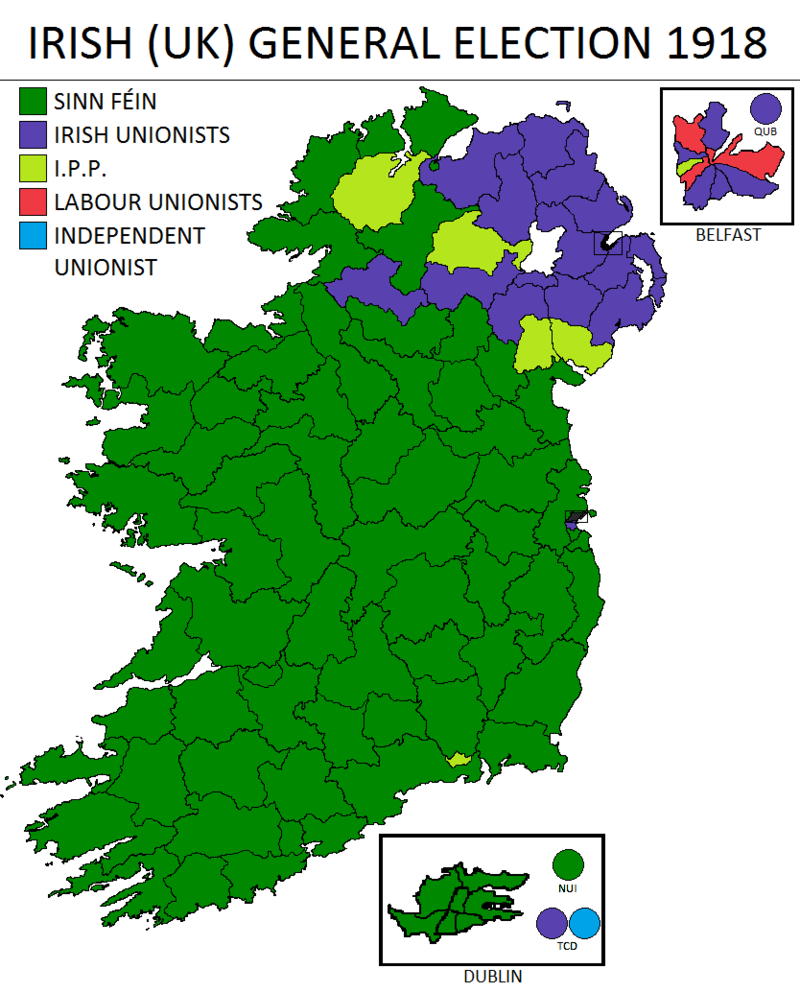

In 1905, Irish nationalists formed the political party Sinn Fein to put these ideas into practice. The name is Irish, and roughly translated means “Ourselves Alone.” Both the name and the choice of language were symbolic.

The nationalism of Sinn Fein meant an Irish Republic free of all forms of British influence—political, cultural, linguistic, and economic. Sinn Fein therefore rejected moderate British solutions, such as the Home Rule bill that was intended to give the Irish autonomy in local matters while still keeping Ireland in the United Kingdom.

Protestant Unionists, comprising approximately 25 per cent of the population, were understandably skeptical as to where they would fit in such an Irish republic.

Having secured a narrow majority among Irish parties standing for the 1918 UK parliamentary elections, Sinn Fein leaders took the results as a mandate to lead a struggle for an independent Ireland and in early 1919 declared an all-Irish parliament in Dublin. For the next two years Irish nationalists and the British government fought a low-level war characterized by ambush and assassination.

|

In late 1921, the British presented a compromise that was accepted by moderate nationalists. Ireland was divided into a 26-county free state that remained in the British Commonwealth while six counties in the northeast, with their Protestant majority population, remained within the United Kingdom.

Sinn Fein and the nationalist paramilitary organization, the IRA, rejected the compromise. They wanted instead all of Ireland united under one independent, republican government. But in 1923, they were defeated and marginalized by the government of the new Irish Free State after a year of traumatic civil war. In 1926, members of Sinn Fein, led by Eamon de Valera, split from the party and joined the Irish Free State as Fianna Fail (“Soldiers of Destiny”).

This new party kept Irish nationalism as its defining characteristic, but chose to work with the Irish Free State, despite its limitations, to pursue the goal of an Irish Republic. Throughout the 20th century Fianna Fail was the most important party in the Irish parliament and de Valera held the position of Prime Minister for 21 years.

Sinn Fein and the IRA continued to reject the 1921 treaty (and with it either the Irish Free State or Northern Ireland) and worked for decades at the edges of Irish politics for an Ireland free of British control.

|

After World War II, the Irish Free State secured total independence from the UK and became the Republic of Ireland.

Uncompromising Republicans from the IRA and Sinn Fein thus found themselves in a position analogous to that of Unionists in the north—they did not trust the British, they rejected the superiority of Protestants in the newly formed government of Northern Ireland, and they were wary of the Irish Republic and its leaders’ willingness to compromise for the sake of political expedience.

“A Protestant Parliament and a Protestant State”

The compromise that ended the war for Irish independence necessitated that in Northern Ireland two mutually exclusive ethnic groups be accommodated within the same political framework, as the six counties of Northern Ireland contained not only Protestants, but a sizable Catholic minority (roughly one-third of the population).

The new government of Northern Ireland tackled this problem in exactly the same way that it had tackled relations with Catholics in the past: discriminatory legislation that served to ensconce the Protestant majority in the region. To this end, the new government changed voting from proportional representation to a simple majority system and then redrew voting districts, first for Northern Ireland’s 73 local councils and then for the Northern Ireland parliament.

These measures were intended to disenfranchise the Catholic minority, even in areas where Catholics actually held a majority. And they were remarkably effective, awarding a virtual monopoly on political power to the Unionists. As a result, the Catholic opposition largely gave up, and Unionist candidates often ran for office unopposed.

Unionist leaders were forthright about what they were doing and why. James Craig (right), the first Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, told his parliament, “All I boast is that we are a Protestant Parliament and a Protestant state.”

For decades the UK government turned a blind eye to the situation in Northern Ireland. As long as Unionist members of Parliament reliably supported whatever party was in power in London, the governing party in turn allowed the Unionists to deny British rights to the roughly 500,000 Catholics in the six counties.

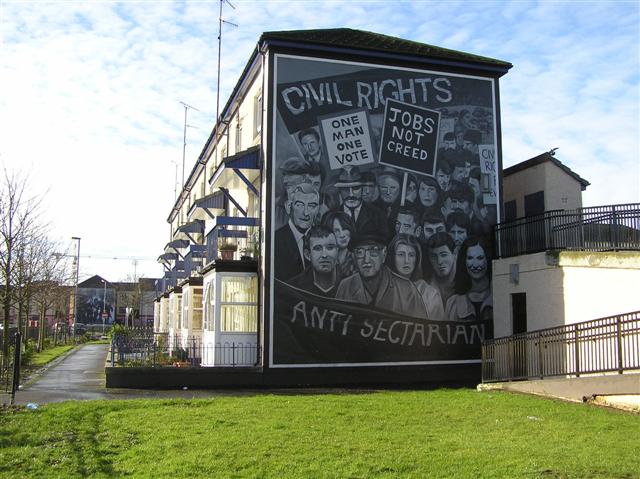

By the turbulent 1960s, this situation was becoming increasingly untenable. Northern Ireland stood out more and more as undemocratic, unfair, and anachronistic. When Catholics organized a civil rights protest movement modeled loosely on that of the United States in the late 1960s, they inadvertently precipitated a crisis.

The Impossibility of Reform

The majority of those in the civil rights movement were reformists, not revolutionaries, and their hope was to receive the equality they were guaranteed as UK citizens. Many Unionists, while uneasy with the challenge to the established order, recognized the legitimacy of Catholic grievances. However, the confrontational nature of political relations between the two communities guaranteed that moderate voices would quickly be drowned out by extremists from both sides.

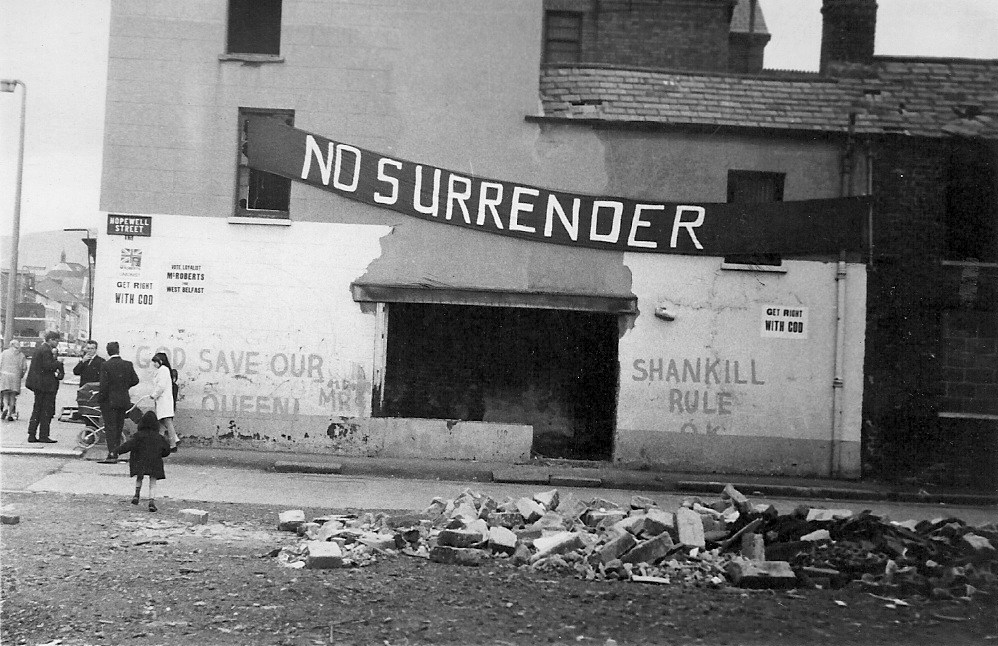

Conservative Unionists saw any concession to the Catholic minority as the first step toward the dissolution of the union and the return of the six counties to Ireland. They were horrified at the thought of becoming an unwilling minority in a much larger Ireland that was to them very much a foreign country in terms of culture, faith, and politics. They fought any concession tooth and nail.

By 1966, small groups of Protestant paramilitaries in Northern Ireland began taking up arms against their Catholic neighbors. By the end of the decade, the civil rights movement had become adversarial, resulting in violent clashes between civil-rights marchers, Protestant mobs, and the police.

|

When communal violence in the north reached a peak in the summer of 1969, the UK government was no longer able to ignore the situation and on August 15 deployed the army to maintain peace in the six counties. However, by using the army, a symbol of the British state, to support the Unionist government of Northern Ireland, the UK government inadvertently escalated the conflict.

At this time, the IRA was too small and too poorly armed to have much of an impact, leaving resentful Catholics in Belfast to joke bitterly that IRA stood for “I ran away.” In response, the IRA split in 1969, with a new, more militant wing called the Provisional IRA recognizing the need to actively defend the Catholic community.

Initially many Catholics had hoped that the UK army would be more impartial than Northern Ireland’s sectarian government and police. However, the army soon began implementing collective punishments against the Catholic community, such as curfews and internment without charge or trial. Catholics therefore came to understand the army as being on the side of the Unionists, which in turn lent credence to the Republican axiom that Catholics could not receive fair treatment in a British state. The IRA’s hardline version of Republicanism became an ever more viable alternative for many Catholics.

Hardline Republicans were re-energized and soon moved from simply defending the Catholic community to assuming the purpose of the original IRA, which was to fight the British government until it unilaterally withdrew from Ireland.

|

Within a few short years, Northern Ireland transitioned from a divided community at peace in spite of itself, first to a community endeavoring to reform and then to a community on the brink of civil war. Nearly 500 people were killed by political violence in 1972 alone as Northern Ireland teetered on the brink of cataclysm.

The impossibility of reform allowed extremists on both sides to hijack the political crisis of 1968-1969 for their own purposes. Unionists used the violence of the IRA to justify maintaining the status quo. Republicans, both in the IRA and in Sinn Fein, used the collusion of British and Unionist power to justify a complete break with the UK.

Political deadlock ensured that for the next 30 years Northern Ireland would remain entangled in a complex tapestry of insurgent terrorism, state repression, communal violence, and personal vendettas and feuds.

Bombs, first delivered by hand and then by car, became the preferred weapon of both Loyalist and Republican paramilitaries. Brutal and indiscriminate, bombs killed and maimed innocent civilians by the thousands. The center of Belfast soon became a burned-out wasteland, crippling commerce, investment, and tourism. In the 1990s, the IRA deployed massive truck bombs against targets in English cities such as London and Manchester, causing billions of dollars in damage.

|  |

The Possibility of Peace

By the early 1990s, several factors converged to make a negotiated end to the violence seem plausible for the first time.

The most development was the decision of Republicans to pursue a political route in addition to their armed struggle. In 1981, 10 Republican prisoners, led by IRA and Sinn Fein member Bobby Sands, fasted to death in a high-profile effort to pressure UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher into recognizing them as political prisoners rather than criminals.

Thatcher refused, but thanks to an unanticipated series of events, Bobby Sands was elected to the UK parliament while still on hunger strike. Although his election did not influence Thatcher, Sands’ success persuaded Sinn Fein leaders to complement the IRA’s armed struggle with a political track, and Sinn Fein candidates began to stand for elections in Northern Ireland and in the Republic of Ireland.

|

In 1986, Sinn Fein took the dramatic step of ending its policy of abstention and began to participate in the Irish parliament, whereas before Sinn Fein candidates who had won elections had refused to take their seats in protest of the lack of legitimacy (in their eyes) of a parliament that represented only 26 Irish counties.

Sinn Fein’s electoral success motivated the British and Irish governments to enter into discussions about Northern Ireland. By late 1993, they had reached a consensus that would form the heart of the Good Friday agreement.

Both governments renounced their claims to the six counties, promising instead that the fate of Northern Ireland would be tied to the political wishes of its citizens. This principle, usually referred to as the principle of consent, made the short-term success of the Good Friday agreement possible by allowing politicians from both communities to claim that their desires—either ongoing union or integration into Ireland—could be accommodated within Good Friday.

Sinn Fein’s turn to politics also led the party to a working relationship with the moderate nationalist party in Northern Ireland, John Hume’s Social Democratic Labor Party (SDLP).

Across the Atlantic, U.S. President Bill Clinton had promised Irish-American groups that he would take a more active role in promoting peace in Northern Ireland, even though this would cause tension with his allies in the UK government. In early 1994, he allowed Sinn Fein president Gerry Adams (below right) to visit the United States to build support and raise funds.

With the Irish government and the SDLP on board as potential allies and the United States willing to play the part of honest broker, moderate members of Sinn Fein had the strength necessary to procure a ceasefire from the IRA in August 1994.

Protestant paramilitaries soon followed with their own ceasefire, and surprisingly issued an apology as well, offering “the loved ones of all innocent victims over the past 25 years abject and true remorse.”

The ceasefires in turn allowed moderate Unionist politician David Trimble the possibility of working with nationalist political parties without appearing to be a traitor.

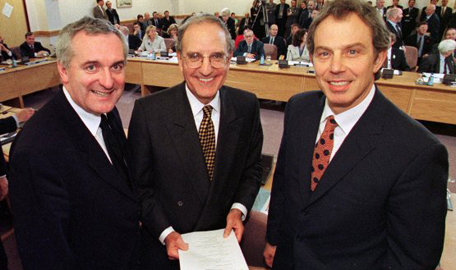

The last piece to fall into place was the election of Tony Blair as British Prime Minister in 1997. With a strong majority in the UK Parliament and a desire to make a fresh start, Blair was not dependent upon Unionist politicians and therefore had both the will and the means to promote a compromise more aggressively than his predecessors.

The United States dispatched former senator George Mitchell to broker the talks. All parties sensed that the conditions for reaching an agreement were as promising as they were likely ever to be, yet they were unable to make headway in 1996 and 1997. Worried that the opportunity might be lost, in early 1998 Mitchell decided to set a firm deadline—Thursday, April 9, the day before the Easter holiday weekend.

The British and Irish governments drafted a framework, sent it to the moderate Unionist and nationalist parties for approval, then finally—not until early on the morning of Good Friday—were able to get the more radical parties such as Sinn Fein on board. Although they missed Mitchell’s deadline by one day, by the evening of Friday, April 10 the participants had a potential deal in place.

What Good Friday Does and Does Not Do

In the following months, the Good Friday agreement was ratified through referendums in both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. As noted earlier, one of the central elements of the agreement was to secure in writing the principle of consent—that neither Ireland nor the United Kingdom would attempt to hold Northern Ireland without the express permission of the majority of its population.

|

The Good Friday accords established cross-border bodies to give Ireland a consultative/advisory role in Northern Ireland with regard to social and political issues. The agreement also established a British-Irish council to provide oversight. One of the agreement’s most challenging provisions was the amnesty and release of paramilitary prisoners from both sides. In the following year hundreds of terrorists, some guilty of dreadful acts of violence, were granted amnesty.

Most importantly, the agreement set up a power-sharing executive branch of government in Northern Ireland. The first minister would be a candidate chosen by the party with the largest share of the vote. The position of deputy first minister was also established and assigned to the largest party of the other community, guaranteeing that the executive would always balance a Unionist against a nationalist.

Thus, in 2007 when Sinn Fein replaced the SDLP as the most popular nationalist party, Martin McGuiness, former leader of the Derry Brigade of the Provisional IRA, became deputy first minister and wound up shaking Queen Elizabeth’s hand.

The Good Friday process does not, however, contain any mechanisms to integrate Unionists and nationalists into interdependent political relationships, nor does it provide incentives for parties to mobilize along anything other than sectarian lines. Quite the contrary, it ensures that political parties will continue to be based on sectarian lines and that public resources such as housing will also be allocated according to sectarian criteria.

Furthermore, the principle of consent was selected precisely because it was ambiguous. David Trimble (right), on the Unionist side, could promise his supporters that it reaffirmed and strengthened the union because it made integration into Ireland impossible so long as Unionists were a majority of the population.

Gerry Adams of Sinn Fein, in contrast, could promise his supporters that it offered the possibility of Irish unity in the future, since differential population growth between Catholics and Protestants had been narrowing the Protestant majority for many years.

Scholar Feargal Cochrane has astutely observed that rather than a definitive resolution to the question of how best to govern all citizens of Northern Ireland equally and fairly, Good Friday really is more an agreement to disagree about the future of the region.

Treating the Symptoms

Like doctors treating a patient on the brink of death, the Good Friday negotiators were under intense pressure to do something to stabilize the situation, or at least to refrain from making it worse.

Now that the situation has indeed stabilized, the difficulty of treating the underlying cause has again become the central issue. The situation of course is made more difficult by the fact that there is no consensus among the political “doctors” as to precisely what ails the patient and therefore no clear path to recovery.

Some undoubtedly believe that the cure is Irish unity, some that the cure is the status quo. More likely a durable cure is to be found somewhere in the middle, through a deeper set of political and social reforms the likes of which were not possible in the 1960s when the Troubles began, but might be possible now.

In recent years, the successful reform of policing in Northern Ireland, an issue so contentious it was left out of the Good Friday agreement, suggests that this may well be the case.

Like some illnesses that have no medical cure, the political malaise in Northern Ireland may not be suitable for outside intervention. Easing it may be dependent upon the underlying health and constitution of the patient, and time and patience.

Daithi O’Ceallaigh, Irish Ambassador to the United Kingdom, suggested somewhat optimistically that the end of sectarianism in Northern Ireland was likely two generations away. If this current generation growing up as part of the Good Friday process can maintain the peace, interdependence does have a chance of following in their children’s time.

Should this prove to be the case, it will strongly suggest that the Good Friday strategy of pragmatically addressing the symptoms of political dysfunction, rather than the root causes, is a valid strategy that may well have application in other conflict ridden societies.