|

Common Core is a set of voluntary standards in the United States for the public education system (K-12) that detail what children should learn in mathematics and language arts. The curriculum guidelines were released in the summer of 2010 and soon forty-four states adopted the shared curriculum. However, controversy arose quickly and several states suspended implementation and attempted to repeal adoption. Debate continues at all levels of government.

From the country’s very origins, Americans have squabbled over public education: from fights over teaching evolution to what the founding fathers really believed to policy debates over student debt, and from battles over teacher tenure, to racial inequality, school funding, and the influence of big business. And debates are all to the good—when there isn’t any more debate, we’ll know we’re in serious trouble.

Common Core is no exception and now faces detractors from both sides of the political spectrum. For the left, represented largely by teachers’ unions, Common Core is an attempt to take away workplace autonomy while imposing more high-stakes testing. Conservatives, meanwhile, decry the impositions of know-it-all federal outsiders encroaching into their local communities.

Most critics today, however, have overlooked these ten historical factors that help explain Common Core and why Americans are so conflicted about it.

|

Will Jeb Bush’s 2016 hopes be hindered by his Common Core support? |

1. A diverse set of interests developed Common Core

While both Democrats and Republicans cry foul over the creation of Common Core, a wide array of interest groups contributed to the development of the Common Core curriculum. Wary of reactionary forces against federal intrusion, the National Governors Association Center for Best Practices and the national Council of Chief State School Officers were the primary actors. But the federal government via the Department of Education and large corporate interests also got to contribute to the process. And so did teachers through the National Education Association (NEA) and the American Federation of Teachers (AFT), among other groups.

2. Common Core is voluntary

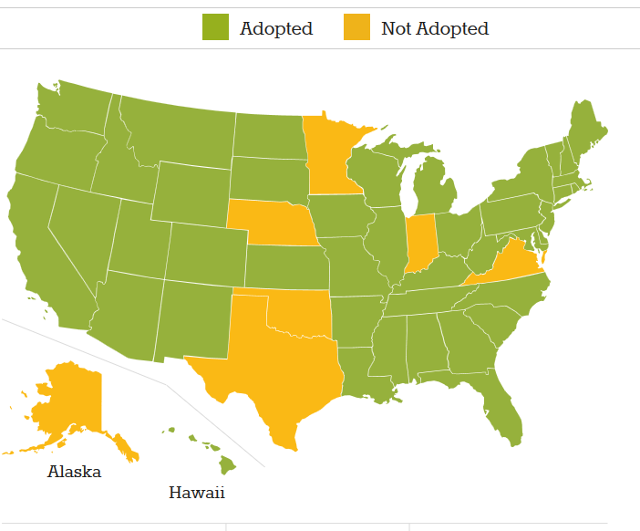

|

As of January 2015, 44 states have adopted both the math and language guidelines (Minnesota has adopted only the language curriculum). Click this link to visit the Common Core standards official webpage for an up-to-date version of this map. |

Far from being a federal mandate, Common Core is completely voluntary. It was this voluntary nature of the program, perhaps more than anything else, that persuaded state politicians to adopt Common Core in the first place. Developed by governors, not the federal government, and with the input of teachers, the new guidelines are exactly that: guidelines. It was only after pushback began in the wake of adoption that politicians publicly turned against Common Core. This pattern follows other major American school reform efforts: get legislatures and local boards of education on a state-by-state basis to pass your reform. In 1925, the school consolidation and standardization movement succeeded in getting 34 separate state departments of education to adopt similar, wide-ranging standardizations for some 40,000 schools across the U.S.

3. The Constitution does not mention education

|

The designers of the Constitution (as seen here in Barry Faulkner’s 1936 mural in the National Archives Museum) had a lot to say about national education, but they did not deem it necessary to insert it into their document. (Click on the link to see which person is which.) |

There is no mention of education in the United States Constitution. Due to the federal system of government, the creation of public education systems fell to local governments. Many early revolutionaries such as Benjamin Rush outlined what they believed a national curriculum should cover—not Latin, not too European, educate for Democracy, separate women’s training. But the founders created no constitutional mechanism to implement a national system. Thus, unlike many other countries, the U.S. has never had a centralized national K-12 system.

4. Americans are highly invested in local control

|

For a whole host of reasons, many segments of American society have long been fully devoted to local control of their schools and to the ideal of the “neighborhood school.” Today, American communities are figuratively and literally invested in their local schools: the district system is based largely on local property taxes; parents desire close proximity to their child’s school building; a romantic ideal of American individualism reacts against perceived outsider influence; and the nation’s troubled racial history has meant that the vast majority of schools have been and continue to be racially segregated and economically unequal. It also means that curriculums vary greatly from one school building to the next.

5. Educational reformers are perpetually “tinkering toward utopia”

|

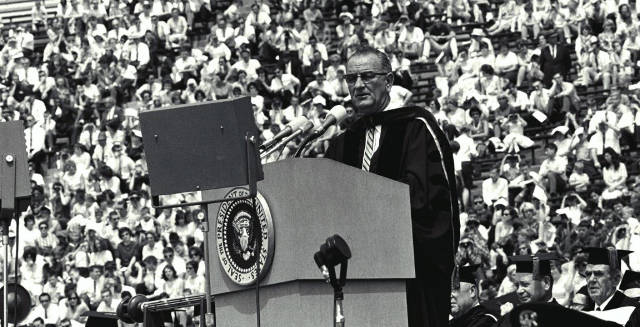

As David Tyack and Larry Cuban pointed out, American history is filled with repeated efforts to reform the country’s education systems. And in all these stabs at improvement, Americans are unrealistic in what they believe education can accomplish. Calling “American’s intense faith in education—almost a secular religion,” Tyack and Cuban prove President Lyndon Johnson’s truism about the nation, that “the answer to all our national problems comes down to a single word: education.” When a reform does not instantly deliver on its inevitably oversold promise, the American public is likely to judge it an instant failure. This tinkering has been continuous throughout the 20th century: the entire education code for California totaled 200 pages in 1900. By 1985 it was more than 2600.

6. This is not the first time a national curriculum has been offered

|

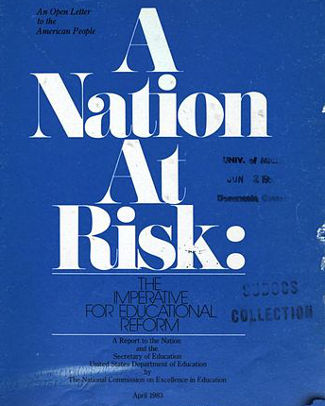

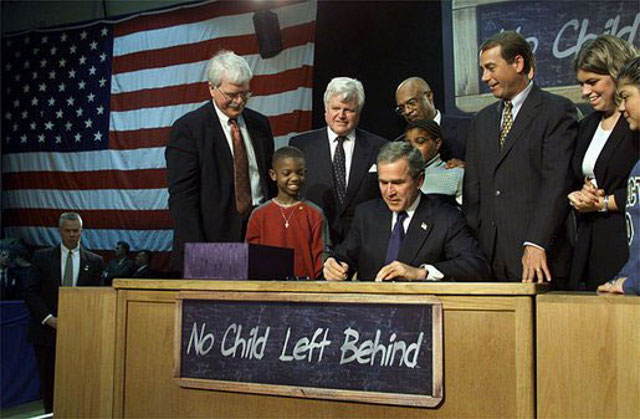

Modern debate over the merits of national curriculum and standards dates to the publication of a report in 1983 entitled A Nation at Risk by the Reagan administration’s National Commission on Excellence in Education. Just as racial desegregation was hitting a high-water mark, the report hyperbolically called for a “national intervention” to battle “a rising tide of mediocrity that threatens our very future as a Nation and a people.” By citing issues ranging from falling test scores to rising international economic competition, it spurred the creation of the federal government’s National Council on Education Standards and Testing which recommended to Congress a series of national curriculum recommendations. In 1989, President George H. W. Bush called for “clear, national goals,” but, as with past national policies, left authority with the local level.

7. Math this time, but history most times

|

While celebrities and comedians have gained national notoriety for challenging Common Core’s mathematics guidelines, history has most often sparked the sharpest national conflict, in large part because it appears to threaten cultural tradition and social convention. After President Bush, Democrats, too, began pursuing national guidelines and backing national standards when President Bill Clinton passed the Goals 2000: Educate America Act. But the topic of history garnered the most blowback such as when the National Endowment for the Humanities commissioned UCLA historians to develop a new curriculum for grades 5-12. Conservatives forced a revision in 1996 of what they saw as the flawed “revisionist history” standards. But, like with Common Core, a majority of the original—and moderate—guidelines remained intact and serve as the guidelines for over 30 states.

8. Common Core combines two aspects of education reform: “standards” and curriculum

|

Common Core appeared at first to have something for everyone but now seems to be pleasing nobody. Conservative educational reformers praise the focus on raising “standards.” Liberals, as backers of federal oversight and influence, support what could be a step in the direction of a national curriculum. Traditionally, liberal eras like the 1930s and 1960s have stressed access and equality over standards. But at least since 1983’s A Nation at Risk, the development of a national curriculum has been attached to rising accountability, characterized by high-stakes testing for school districts, teachers, and often administrators. Today, the political balance is unevenly weighed in favor of standards and accountability, which tend to economically punish individual teachers or schools for shortcomings that are really caused by other factors like socio-economic and racial inequality.

9. Technology and lower values placed on formal education further limit the appeal of a national curriculum

|

Will technology lead us down increasingly individualized paths? |

The Common Core debate shares much with earlier efforts at educational reform, but there is also something new here. While some argue that technology is opening up educational opportunities to more people than ever before, technology also threatens to narrow the scope of learning while also devaluing schooling not deemed immediately economically valuable. Technology has supposedly placed MIT-level courses at our fingertips via MOOCs. But as individuals have more control over what they choose to learn, the appeal of a national, consistent, common curriculum lessens. The question arises: why can’t I—or my son or daughter—just study what I want?

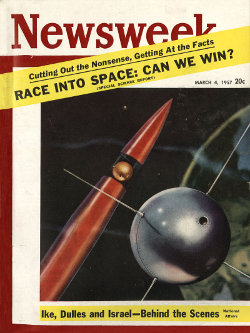

10. International competition fears have often sparked reforms

|

Fear over international economic competition—that the U.S. is falling behind other countries—is nothing new. Spikes in concern of this type have most often occurred during eras of conservative ascent. In the 1890s, Americans were concerned with keeping up with the Germans, in the 1950s with the Soviets who launched Sputnik, and in the 1980s with the “economic miracle” of Japan. It seems likely that future historians will look back to the reforms of the 2000s as a time when the U.S. stressed the struggle for national survival against both a rising Asia (think South Korea) and an established Northern Europe (think Finland).