Since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the Russian Federation has scrambled to recover from territorial losses in eastern Europe and Central Asia, widespread corruption in the private sector, and a decline in its international reputation and superpower status. Its narrowing, unstable economy has become dependent on the export of a single commodity: energy.

Energy production in Russia, in addition to its economic and geopolitical implications, is an environmental threat. Gazprom, the powerful oil and natural gas company, has a history of undertaking developmental projects that are poorly regulated and ecologically damaging. We should take these environmental concerns seriously.

One of Gazprom’s most ambitious projects—the Nord Stream 2 pipeline—could potentially double the carrying-capacity of an existing pair of offshore Russian lines currently supplying Germany through the Baltic Sea.

As of February 2021, the pipeline has reached 94% completion, and the prospect of its imminent launch has caused consternation among U.S. policymakers. The State Department, in fact, promised to do everything in its power to ensure that the pipeline does not “threaten Europe.”

Just what is so threatening about a new Russian pipeline? While the U.S. might fret over the increase in Russia’s influence over the European economy, the real danger lies in Nord Stream 2’s potential environmental impact.

Soviet environmental policy and “brute-force technologies” left a destructive legacy across much of the country’s ecology.

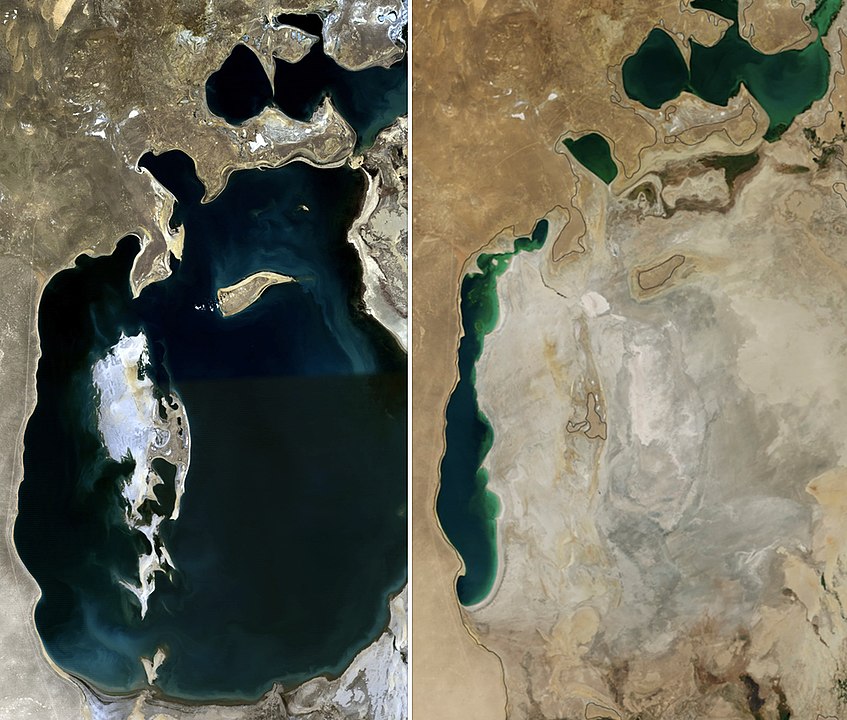

In the early-twentieth century, industrial nickel smelting processes produced thousands of gallons of heavy-metal waste, which were dumped into rivers in the Russian Arctic. In the Soviet era, large-scale irrigation in Central Asia led to the desiccation of the Aral Sea.

A comparison of satellite images of the Aral Sea in 1989 (left) and 2014 (right).

As Soviet industrial planners erected entire cities from the ground-up for the purpose of producing iron and steel, the quality of life of Russian city-dwellers in emerging metropoles like Magnitogorsk, Novokuznetsk, and Ekaterinburg was affected by the proliferation of urban detritus.

And as Soviet agriculturalists poisoned parts of the earth through the indiscriminate use of DDT and chemical fertilizers, nuclear pollution from power plants in Chernobyl and Ozersk irradiated others. The destructive activities undertaken by the USSR have been labeled by some scholars as “ecocide.”

Gazprom is no different.

The company’s CEO, Alexey Miller, declared that 2013 would be the “year of ecology” for his company, which had introduced “breakthrough technologies” such as the conversion of thousands of vehicles to natural gas and the installation of solar cells at production facilities.

The CEO of Gazprom Alexey Miller (left). Gazprom's headquarters in St. Petersburg (right).

Baltic states like Finland and Lithuania have expressed concern that the pipeline, which will run through the Baltic Sea, poses a risk to delicate marine ecosystems. Similar discussions between cartographers, geologists, political scientists, and ecologists in Scandinavia emphasize the project’s potential to unearth dangerous, WWII-era mines that lie unexploded on the seafloor, thousands of unopened barrels of Nazi mercury, and other chemical munitions.

Environmental history teaches us that the processes associated with ecological modernizing projects that go on behind-the-scenes can, in many cases, be the most hazardous to the environment. These hazards are often hidden behind projections of clean energy, which companies like Gazprom use to convince the public of the desirability of further development.

The activities of Russian energy companies over the past 30 years have led to several environmental disasters. The Moscow Times has highlighted the impact of the 2011 Kolskaya oil rig disaster on the salmon, red king crab, halibut, pollock, and marine organisms off the coast of Kamchatka (as well as the death of 53 oil-rig workers).

Just recently, 20,000 tons of diesel fuel leaked from the Norilsk thermal power plant into local waterways and led Russia’s state fishing agency, Rosrybolovstvo. to declare the accident an “ecological catastrophe.”

Generating energy in Russia has long been a dirty business.

Gazprom’s rosy assessment of Nord Stream 2’s environmental impact might not be entirely sincere, either. The pipeline has its origins in Russia’s Kurgalsky Nature Reserve and runs through the Baltic Sea into Pomerania. Greenpeace Russia and other environmentalist groups have already led a backlash.

Any leakage from Nord Stream 2 or pollution generated from its construction would be a violation of the 1992 Helsinki Convention on the Protection of the Baltic Environment and the Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes.

Some publications have even suggested that Gazprom is bankrolling the Ramboll Group, the scientific consultancy company that provided a positive environmental assessment of the pipeline’s construction.

As the venerated American environmentalist Rachel Carson once said: “A grim specter has crept upon us almost unnoticed, and this imagined tragedy may easily become a stark reality we all shall know.”

Carson’s message is just as relevant for Nord Stream 2 today as it was for the use of pesticides in the twentieth century. For the lessons we mine from both DDT and natural gas are essentially the same: too great a confidence in our ability to turn the natural world to our advantage may make the ghosts of yesterday’s promise the demons of tomorrow.