Since the beginning of 2015, more than one million people have arrived to Greece as refugees, fleeing war, destruction, and persecution in their homelands. As the already beleaguered Greek state, bolstered by the European Union, struggles to deal with this massive influx, humanitarian organizations and individuals have stepped in to provide food, clothing, and shelter to these vulnerable people. This March, I joined them, spending a week volunteering with a friend at a makeshift refugee camp at the port of Piraeus, just outside Athens.

Our trip to Greece coincided with an especially chaotic period in the refugee crisis. On March 18th, the European Union and Turkey signed an agreement beefing up Turkish efforts to prevent refugees from reaching Greece by sea. These new measures drastically reduced the arrival of refugees almost overnight. But its other provisions, designed to establish an orderly resettlement process for qualifying asylum seekers already in Greece, lagged far behind.

Earlier that month, meanwhile, Macedonia had fully closed its border to Greece, slamming the door shut on the so-called “Balkan Route” that more than a million refugees had traversed through southern and Eastern Europe towards wealthier and presumably more hospitable northern European nations like Sweden and Germany.

The "Balkan Route." (BBC News, 4 March 2016)

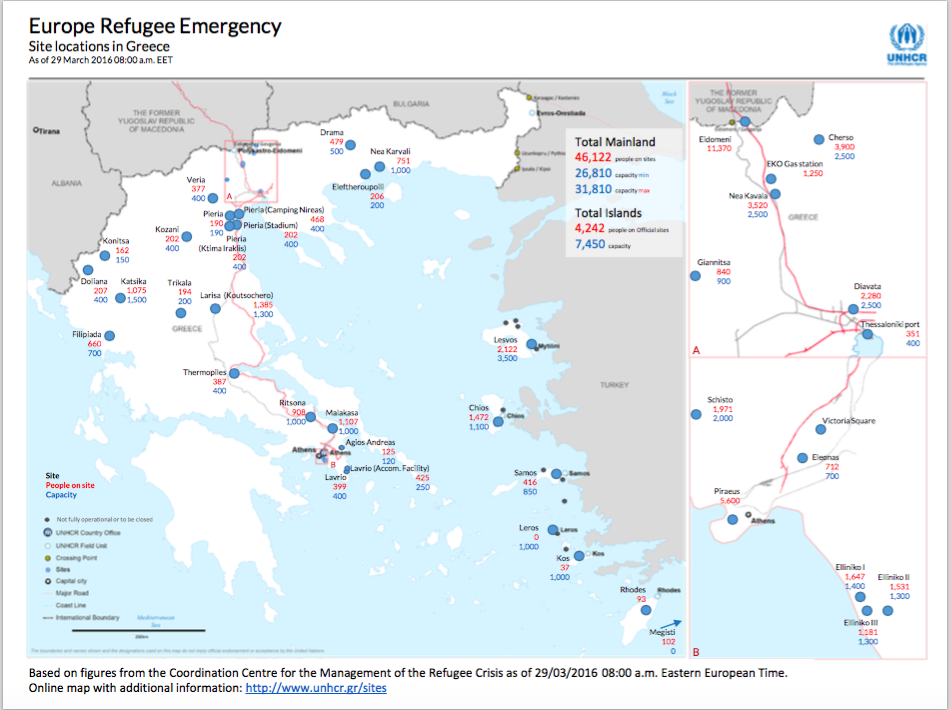

At the moment of our arrival on March 28th, then, refugees had largely stopped landing on the Greek islands off the coast of Turkey. Fifty thousand people already in Greece, however, were left stranded in the country.

Total refugees housed in Greece on March 29th, one day after the author's arrival. (United Nation High Commissioner for Refugees)

We came to Greece with only a vague sense of how we might be of use, having seen a Facebook post calling for volunteers. My friend Kelly had previously spent time on the island of Lesbos, where an elaborate and highly organized volunteer ecosystem had developed to deal with the huge numbers of refugees arriving from Turkey via small boat. Now that the boats had largely stopped, however, these NGOs struggled to move their operations to the mainland to serve the large populations now living in increasingly precarious and unofficial circumstances—including over five thousand people inside the port itself.

Refugee tents in Piraeus port. (Photo by author)

One of Europe’s busiest harbors, the port facilities at Piraeus lack any significant amenities or housing. We found people sleeping in tents underneath shipping compartments or on meager strips of grass, a mere stone's throw from where they'd been dropped off by ferries from the Greek islands. Some passenger terminals became impromptu shelters, providing a measure of protection from the elements for those without tents. All around them, the port continued its normal function as a commercial and passenger hub. More than once, I saw disembarking tourists stop to take photographs of refugees, before wheeling their suitcases out to the waiting taxi cabs.

Laundry strung between two parked trucks in Piraeus. (Photo by Kelly Sanabria)

Kelly and I spent most of our time at an abandoned warehouse between two ferry terminals, known colloquially as the Stone Building or Stone House. Nearly 1,500 people lived here in rows upon rows of tents, without heating or plumbing. The only source of water came from a single hose, which ran through a hole in the wall from the outdoor showers and toilets.

Stone House. (Photo by Kelly Sanabria)

Each day, we arrived at Stone House in the late morning, and ducked around the metal grates that separated a small supply area from the rest of the building. For the next eight to ten hours, we worked there, manning the hose, using it to fill the water coolers from which we served water and weak tea to a procession of refugees from Stone House and other surrounding encampments. We also handed out a meager selection of donated toiletries: shampoo and body wash, laundry detergent, disposable razors.

Everything was in short supply, so we were forced to strictly restrict what we gave away, chopping bars of soap into thirds and asking people to please reuse their flimsy plastic cups. After the first day, we would stop by the supermarket on our way to Piraeus and stuff our bags full of whatever we’d run out of the day before, but it was inevitably never enough.

The author, with a collection of toiletries and other items purchased to be donated. (Photo by Kelly Sanabria)

Most of the other volunteers at Stone House were Greeks from the area, propelled to help stem the crisis unfolding in their own backyards. Drawing from the rich history of anarchist and other leftist political organizing in Greece, Stone House operated as an explicitly cooperative space, with volunteers and refugees treated as equal partners. Many of the Greeks we spoke with, at Stone House and elsewhere, viewed the EU's failure to do more for these refugees as directly analogous to the harsh financial measures imposed on Greece by Europe's central monetary bodies.

A pro-refugee banner from Piraeus. (Photo by author)

A large number of the refugees themselves worked in the supply area, as well as serving all the daily meals (delivered by an outside organization). Their efforts created continuity of service as volunteers like us came and went, and fostered communication beyond simple requests for "Tide," "Gillette," or "Pampers." (American brand names largely served as our lingua franca.) Although I speak a little Arabic, and many of the people who approached us spoke quite good English, having a person who could more effectively communicate with a refugee seeking help proved immensely valuable.

Food distribution outside Stone House. The refugees were separated by gender and by nationality: lines for men and women, and Syrians/Iraqis and Afghans. A refugee from each group gave out parcels to their fellow nationals, to prevent arguments and accusations of bias. (Photo by Kelly Sanabria)

It also gave us a valuable opportunity to get to know refugees as individuals. Abdul, for example, had studied civil engineering at university in Afghanistan, and had completed a job-training program sponsored by USAID. He eagerly showed us photos on his phone celebrating Thanksgiving at his job with an American contracting firm—Abdul and another Afghan coworker, giving a thumb's up in front of a paper turkey as Americans mill around in the background.

His next photos showed the aftermath of a January suicide bombing at the contractor compound: the partially-destroyed building, and Abdul himself, bloodied and injured. He'd left the country soon afterwards, fearing for his life as someone who'd worked with the Americans. Now, he was trying to get to Germany, where his brother has lived for over a decade. His biggest goal, he told me, was to go back to school.

Almost all the people we met on a daily basis working at the Stone House came from Afghanistan, Syria, or Iraq. This anecdotal experience tracks with the UN High Commissioner for Refugees' estimate that 91% of people arriving in Greece since January 1 have been from these three countries. Nearly 60% of those arrivals were women and children, in sharp contrast to far-right claims of hordes of young single men pouring into Europe.

Here, too, the demographics of Stone House mirrored the larger statistics. Most of the tents were occupied by family groups, whose members ranged in age from elderly men wearing traditional Syrian garb, to infants (born in the camp itself) whose mothers bathed them in plastic buckets. In fact, one of our most frequent tasks was preparing baby formula—not an easy feat, given that all the instructions on the donated cans were written in Greek.

A refugee family walking around the perimeter of the port complex. (Photo by Kelly Sanabria)

Sometimes, these groups were trying to meet up with a male relative who’d gone to Germany ahead of them. Much like immigrants to America at the turn of the century, these fathers and brothers had then sent for their families to join them.

Samir and Hisham, for example, were two Iraqi boys who often came to visit us while we were serving tea. Both fourteen, they had traveled with their mothers and siblings, and were trying to reach Germany to reunite with their fathers. Already, Samir told us, they'd been in Greece for over a month. When we asked what they did all day, Hisham shrugged and said, "we play football," suggesting the boredom and lack of activity that pervaded the camp.

To help pass the time, I started up a little vocabulary exchange during quiet moments in Stone House—they'd point something out to me and tell me the word for it in Arabic, and I'd give them the German word. They took to the game quickly, eager to for something to do and a way to prepare for their family's reunion in Germany. None of us mentioned the new EU border regulations, or its new resettlement program, which might send their families to a completely different country.

Samir and Hisham. (Photo by Kelly Sanabria)

One of the most striking aspects of Stone House overall was the number of children. Hundreds of them ran around the port, often as young as four or five. While we'd read about volunteers setting up schools, nothing had been established in our area so far. Volunteer groups provided arts and crafts activities once or twice a day, but largely they were left to make their own fun: throwing rocks into the port and "fishing," for example, or trying to sneak into the supply area of Stone House and steal juice boxes, or fistfuls of sugar.

"Fishing" in the port. Adults actually caught and consumed fish from these brackish waters. (Photo by Kelly Sanabria)

Kelly and I made a point to spend at least an hour or two each day playing with the children outside of the cramped confines Stone House. We scoured the shops for things to bring that might entertain them: a rainbow-array of different chalks, for example, or small bottles of blowing bubbles. Those bubbles proved such a welcome success when we first brought them that we ended up having to ration those, too, arranging the children into lines to share a single bottle at a time, each of them taking turns to blow bubbles.

The author and friend, playing with children outside of Stone House. (Photo by Andrea Zipfel)

After that, I spent the next few days experimenting to develop our own homemade bubble solution from dishwasher detergent and corn syrup. I bought a box of one hundred plastic straws, and cut the bottoms of each one so that they fanned out to create makeshift bubble "pipes" for each child to blow into. Of course, all this careful preparation devolved into chaos in practice—I wound up covered in soap, having somehow become the favored target for two dozen bubble-blowing children. Still, despite the hours of sticky discomfort that followed, it was the most fun any of us had had in days.

The author, teaching a small Afghan girl to blow a bubble. (Photo by Andrea Zipfel)

Since leaving Piraeus, Kelly and I have both followed the subsequent developments in Greece closely. Even before we left, the government had begun to clear out the camps at Piraeus. As more official government camps began operation, and the spring shifted into the summer peak tourism season, pressure increased on those who remained, and conditions continued to deteriorate. The last refugees in Stone House left at the end of July.

According to other volunteers who remained, the living conditions in these new government camps are usually better than they ever were at Stone House. The sense of being trapped in limbo, however, has only grown, especially for Afghans, who are not eligible for one of the 160,000 relocation spots the EU has set aside for refugees in Greece and Italy. Even those Syrians and Iraqis who do qualify, however, face daunting delays—so far, only 4,000 people have actually been resettled.

The author, sharing a juicebox with a Syrian refugee child. (Photo by Kelly Sanabria)

Six months after leaving Piraeus, my experiences there have been transformed from an eyewitness testimony of current events, to a historical account. Public interest has largely moved on from Greece, the sense of urgency among the wider world dissipated. Yet the crisis has not ended for tens of thousands of people—men, women, and especially children—still waiting to start their new lives.

Note – All names have been changed to ensure the safety of individuals mentioned in this piece. Where necessary, photos have also been edited to obscure individual identities.

Lauren Henry also volunteers for AreYouSyrious (https://medium.com/@AreYouSyrious), a daily newsletter written by volunteers in Greece and elsewhere. It serves as an information clearinghouse for the latest updates on the ground.