Once again U.S. Army bases named for confederate leaders are in the news cycle. The outgoing president vetoed the 2021 National Defense Authorization Act over a provision that mandates base renaming among other grievances. President Trump’s action forced a congressional override vote—the first of his presidency—to provide funding to the national defense establishment and with it long overdue name changes.

This debate over renaming military bases, which may now be concluding, is not new. The names should have been changed a long time ago.

The Confederate Monument to Robert E. Lee was removed from its perch in New Orleans in 2017.

Base names, like statues, represent historical memory. They showcase what a society reveres. In the attempt to destroy the Union, Confederates stood as enemies of the United States. Enemies should not find themselves memorialized in a country they attacked.

However, as the United States sought reconciliation in the aftermath of the Civil War, a Lost Cause narrative took hold among southerners and sympathizers that portrayed the Confederate cause as an honorable fight for decency and liberty.

In the first decades of the 20th century, national memory of the war conveniently omitted questions of race and emancipation―all in the name of reconciliation for the North, and self-justification for the South. Naming bases became yet another form of historical white washing. As the nation continued to heal from the devastation of the American Civil War, training bases dotting the states of the former confederacy were named for former rebel leaders.

My first experience with Army life came during training at Fort Benning, Georgia. Like most young privates, I was more concerned with the heat and humidity than about the person for whom the base was named. The first time I ran along Longstreet at Fort Bragg in North Carolina more than a decade later, like many paratroopers before and since, I had no clue about its name.

We assumed it was named because it was, in fact, a long street. We were unaware that it carried the name of a one-time traitor who helped orchestrate the deaths of thousands of American soldiers. After the Civil War, James Longstreet atoned for his traitorous behavior better than almost any other Confederate officer. He served in the Grant administration and rebuked the Lost Cause myth that portrayed the Secessionist cause as just—a noble defense of the Southern way of life. For that he got a street named for him.

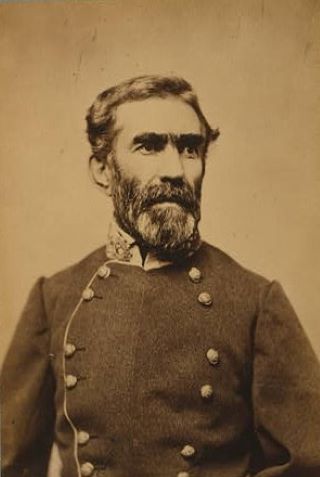

Meanwhile, the base’s namesake—Braxton Bragg—was hardly that honorable. A “cantankerous leader,” Bragg supported seceding from the United States in the name of preserving slavery. Yet this is the person whose name graces the home of the Airborne and Special Forces. No one asked: What kind of message does it send to soldiers to name one of United States most important bases after a white supremacist?

While other names were suggested, Army officials preferred shorter names of five letters or less. Gen. William J. Snow—the Army’s Chief of Field Artillery and in charge of naming efforts—wrote in his memoirs that the installations should be named for officers who had a connection to the place where they were located. The Army needed local “buy in” to build sprawling bases on large swaths of land to train historically large armies for both world wars.

Fort Bragg was christened Camp Bragg in 1918, according to the post’s official history page. The Army justified naming the fort for Bragg because of his performance in the Mexican American War—making no mention of his later treason. At the time, Camp Bragg was only a dot in a network of army installations named after notable and infamous Confederates, of which ten remain.

Signage outside Fort Bragg, North Carolina

All these bases were named just as monuments and statues honoring the Confederacy were constructed throughout the American South. This trend was not accidental but, as a report from the Southern Poverty Law Center outlines, coincided with segregation in the Jim Crow era. Thus, military bases, like public monuments, were all symbols of persistent white supremacy in America and part of its darkest history.

Today we are confronted by the legacy of these ideologically motivated moves from the Jim Crow era. The opportunity to change our common legacy rests fully in our hands. Renaming these bases to reflect the values we seek to transmit to posterity is an imperative. And it is hardly difficult to find more worthy names for these bases.

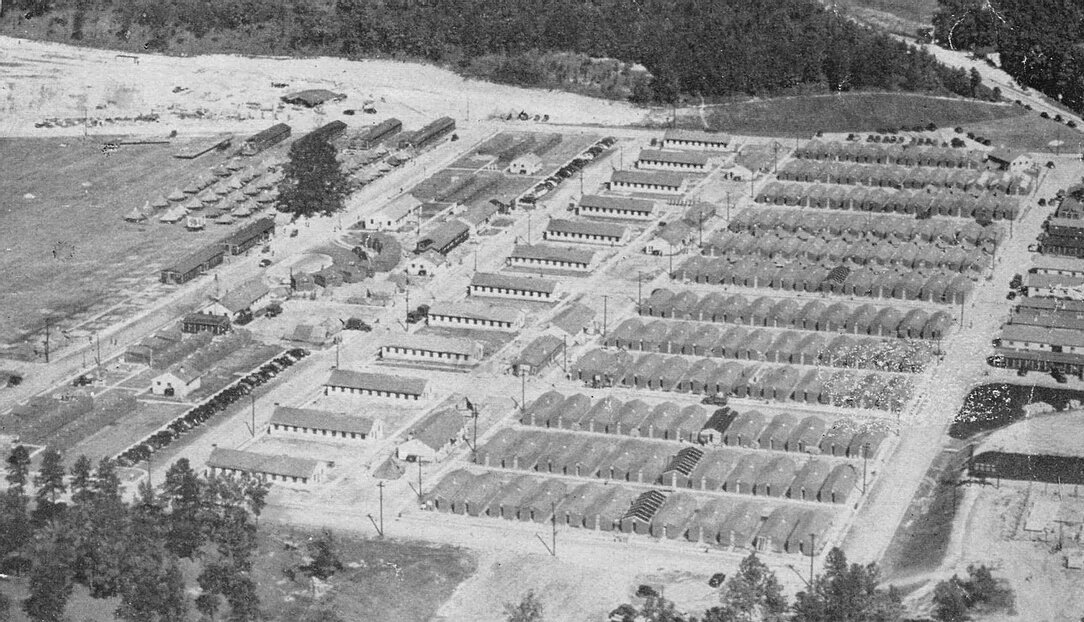

One of the most famous training camps of World War II was named for a Confederate general. Camp Toccoa, the ancestral home of many airborne units, was dedicated in 1940 as Camp Robert Toombs. Toombs, like Benning, was a mediocre Confederate officer. He was once a senator from Georgia, served as the Confederate Secretary of State, and fled to Cuba after the American Civil War.

In 1942, at the behest of Robert Sink, commander of the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, the U.S. Army renamed Camp Toombs as Camp Toccoa. The camp has become famous by virtue of the HBO miniseries Band of Brothers.

Col. Sink decided the camp name needed to change and took it upon himself to make it happen. His reasoning was not because of the traitorous origins of the name—instead he wanted to make the change for a more straightforward reason. As it was, prospective paratroopers disembarked a train in Toccoa and traveled Route 12 past the Toccoa Casket Company before arriving at a camp named Toombs to learn how to jump from aircraft while in flight. While the name was not changed for anti-racist reasons, the story proves that the endeavor is possible.

Recent history has provided new and powerful examples of change in action, including the Department of Defense’s recent decision to ban the display of the secessionist flag on bases. The United States Army will soon no longer venerate men who chose secession and slavery over unity and freedom for all. There is no justifiable reason for the descendants of enslaved persons—for any American soldier—to serve on installations named for those who endorsed and profited from a system of dehumanizing enslavement and then fought to perpetuate it.