Musicals are the quintessential American dramatic art form, combining spoken dialogue with music, song, and dance. For many, musical theater provides an escape from reality, a fantastical journey to a world of singing and dancing cats and magical nannies who travel via flying umbrella.

Yet, musicals have also sought to bring history to life onstage, with varying degrees of creative license. Here are Origins’ top ten musicals based on real-life people and events that have shaped the theatre.

1. Evangeline, or The Belle of Acadia (1874)

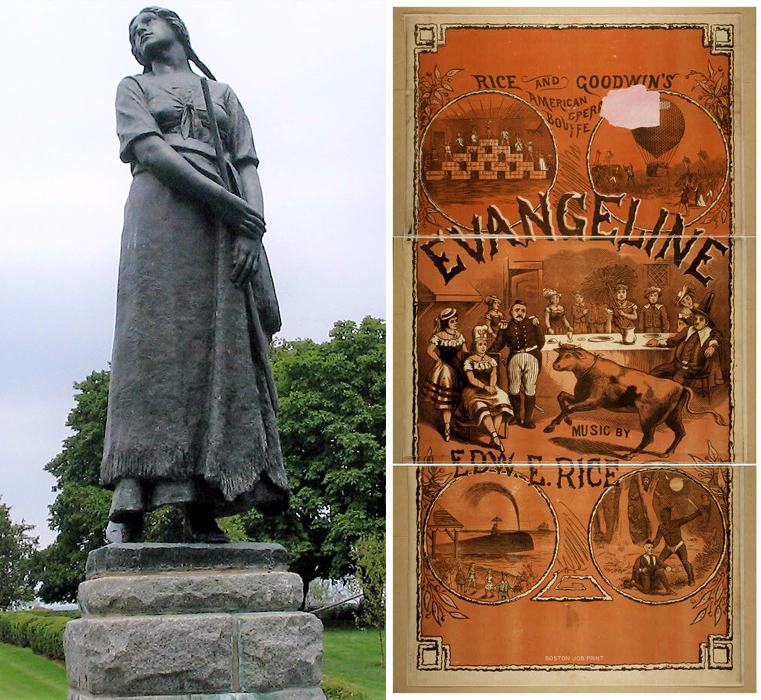

A statue devoted to Evangeline in Grand Pré, Nova Scotia (left); a theatrical poster advertising an 1878 production of Evangeline, or The Belle of Acadia in Boston (right).

Musical theatre as we know it today emerged in the United States and the United Kingdom at the end of the nineteenth century from a variety of antecedents: music halls, minstrel shows and vaudeville, as well as operas and operettas. In early precursors of the genre, often referred to as burlesques or extravaganzas, the plot served as an afterthought, a device merely to string together a succession of musical numbers to entertain the audience. Narrative took a backseat to spectacle.

Although these proto-musicals rarely dealt with actual historical subjects, some did adapt familiar historical characters from folklore. One of the most famous was Evangeline, or The Belle of Acadia, and was based on Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s epic poem about an Acadian girl seeking her lover after they were separated during the forced removal of French Acadians from British Canada.

"In Love With the Man in the Moon," from Evangeline, or The Belle of Acadia.

Composer Edward E. Rice and librettist J. Cheever Goodwin kept the star-crossed lovers, but substituted spectacle for tragedy, sending Evangeline and Gabriel everywhere from the American West to Africa and adding in a dancing cow for good measure. Audiences didn’t seem to mind the tonal departure – Evangeline was wildly popular, and was regularly performed around the country over the next several decades.

2. The King and I (1951) / The Sound of Music (1959)

A promotional still from the 1951 Broadway production of The King and I (left); A promotional still from the 1959 Broadway production of The Sound of Music (right).

Over the next several decades, musical theater gradually evolved into the format we recognize today: spoken dialogue, interspersed with songs that serve to explore character motivations, highlight key themes, and advance the plot. But it was only in the early 1940s that the Golden Age of musicals began, driven largely by the collaboration of composer Richard Rodgers and lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II. Together, Rodgers and Hammerstein created some of the most iconic musicals of all time.

While several of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s musicals took place in the historical past, only two of their musicals were based on real-life individuals. The King and I tells the story of an English governess to the children of the King of Siam (modern-day Thailand). The duo's final collaboration, The Sound of Music, premiered on Broadway only nine months before Hammerstein's death with a similar plot: a young, irrepressible governess tasked with caring for seven unruly children falls in love with their widower father, on the eve of the Nazi German annexation of Austria.

"Shall We Dance," from the 1956 film adaptation of The King And I.

In both cases, the bare bones of the stories were true, yet Rodgers and Hammerstein embellished freely. While the real-life Anna Leonowens really did teach the children of King Mongkut from 1860 to 1867, for example, the suggestion of a romance between the two originated in Anna and the King of Siam, the 1944 novel that Rodgers and Hammerstein used as their source for the musical. And while The Sound of Music ends with Maria, Captain von Trapp and the children heroically on foot to Switzerland in order to avoid the Captain’s imminent impressment in the German Navy, a quick glance at the map reveals that “climbing every mountain” out of Salzburg….would land you in Germany. (They actually took the train.)

3. Fiorello! (1959)

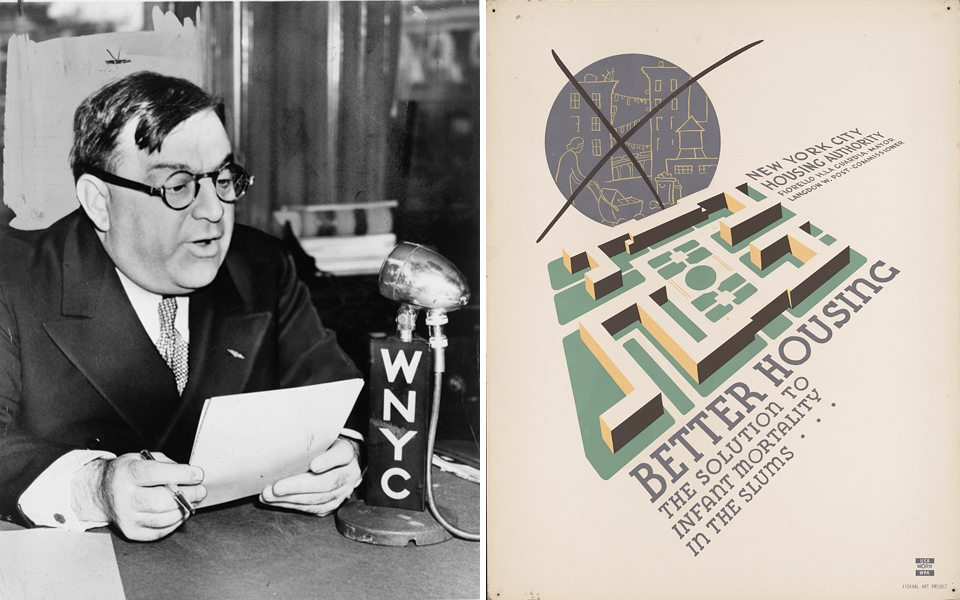

New York City mayor Fiorello H. LaGuardia speaks to the people of New York on his radio show in 1940 (left); a New York City Housing Authority poster c.1936-1938 bearing Mayor LaGuardia's name (right)

Unlike Rodgers and Hammerstein, the creative team behind 1959’s Pulitzer Prize-winning musical Fiorello! were far more limited in their ability to take creative license. Not only was their setting – New York City in the early 20th-century – innately familiar to Broadway audiences in a way that Salzburg or Siam were not, but their titular protagonist, New York City mayor Fiorello H. LaGuardia, was one of the most famous public figures in the city's history.

In Fiorello!, playwrights Jerome Weidman and George Abbott, lyricist Sheldon Harnick, and composer Jerry Bock focus on LaGuardia’s life before becoming mayor: from his early work as a lawyer representing striking garment workers, and his military service in World War I, to his time in Congress and first, unsuccessful run for mayor.

Known as the “the Little Flower,” LaGuardia served three terms in office, from 1934 to 1945, and remains one of the most popular mayors in New York City history. A progressive Republican who supported the New Deal, La Guardia transformed the city as few mayors had done before (or have done since). During his time in office, he took on the entrenched power of New York’s infamous Tammany Hall political machine, oversaw the creation of the New York City Housing Authority to create new affordable housing and greatly expanded the city’s infrastructure with new roads, parks, and airports.

"Politics and Poker," from the original Broadway cast recording of Fiorello!

Fiorello!’s interest in what might be considered small-bore local politics reflects the centrality of New York City to musical theater. For more than a hundred and fifty years, “Broadway” has been synonymous with professional theater, and dozens of musicals have been set in the city. In fact, LaGuardia himself helped cement the relationship between New York and the theater, when his administration founded a public school to train future actors, artists, and musicians in 1936 – today the Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts.

4. 1776 (1969)

"The Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776," by John Trumbull.

Given the political and cultural schisms that divided America in 1969, it’s all the more shocking that 1776 was a hit with audiences of all persuasions. Yet Sherman Edwards and Peter Stone’s stirring dramatization of the signing of the Declaration of Independence was a genuine sensation, running for 1,217 Broadway performances and sparking a 1972 film adaptation.

1776 depicts the Founding Fathers as complex, flawed men whose personalities clashed almost as often as their ideals. John Adams, brilliant, principled, and “obnoxious and disliked” in equal measures, harangues, cajoles, and coaxes his fellow delegates to support American independence. He is abetted by the sly, jovial Benjamin Franklin and a talented yet lovesick Thomas Jefferson. Presented as a work of dramatic realism, with many lines drawn directly from the characters' real writings, 1776 appealed to Republicans and Democrats alike, with each side claiming the musical's message for their own.

But even 1776 could not escape the era’s partisan politics entirely unscathed. When President Richard Nixon invited the cast to perform the show at the White House in honor of George Washington's birthday in 1970, his office requested that they excise three of the show's more openly political numbers: “Cool, Cool, Considerate Men," a satirical minuet performed by the conservative members of the Constitutional Congress; “Molasses to Rum to Slaves,” a critique of northern hypocrisy about slavery from South Carolina representative John Rutledge; and “Momma, Look Sharp,” which describes the Battle of Lexington from the perspective of a dying soldier.

The cast and producers pushed back, insisting that they would perform the show in its entirety or not at all, and eventually the White House backed down. Two years later, however, Nixon successfully lobbied the film’s producer, a prominent Republican, to have “Cool, Cool, Considerate Men” removed from the film version.

5. Evita (1979)

The real-life Eva Perón, giving a speech in 1951.

Ever since her premature death in 1952, Eva Perón, former first lady of Argentina, has been depicted in everything from comic books to the design of an entire neighborhood, shaped in her profile. None, however, have had as much influence as composer Andrew Lloyd Webber and lyricist Tim Rice’s musical Evita, which opened on Broadway in 1979 after its West End debut a year earlier.

The plot tracks Evita’s rise from poverty to become a celebrated actress in Buenos Aires, where she meets and later marries future president Juan Perón. Evita was wildly popular among the poor, who saw her as a primary advocate in her husband’s administration. The musical was written in the wake of the right-wing coup that toppled Juan Perón’s successor (and third wife) Isabel, and has often been accused of pushing an anti-Perónist agenda through the character of Che, a fictionalized everyman who represents the voice of the people. The impact of Che’s sharp criticisms of Evita’s ambition and extravagance, however, have been blunted by the passage of time and by the perennial popularity of “Don’t Cry For Me, Argentina.”

"Don't Cry for Me Argentina," from the 1996 film adaptation of Evita.

While the politics of Evita remain difficult to assess, its place in musical theater history is unambiguous. The first British musical to win the Tony Award for Best Musical, it signaled the arrival of a new trans-Atlantic era on Broadway, with the importation of several successful West End productions. The grandiose scope of these “mega-musicals” often involved elaborate historical settings: from Weber’s The Phantom of the Opera (Belle Epoque Paris), to Miss Saigon (1970s South Vietnam) and Les Misérables (1830s Paris), and required increasingly elaborate technical effects.

6. Assassins (1990)

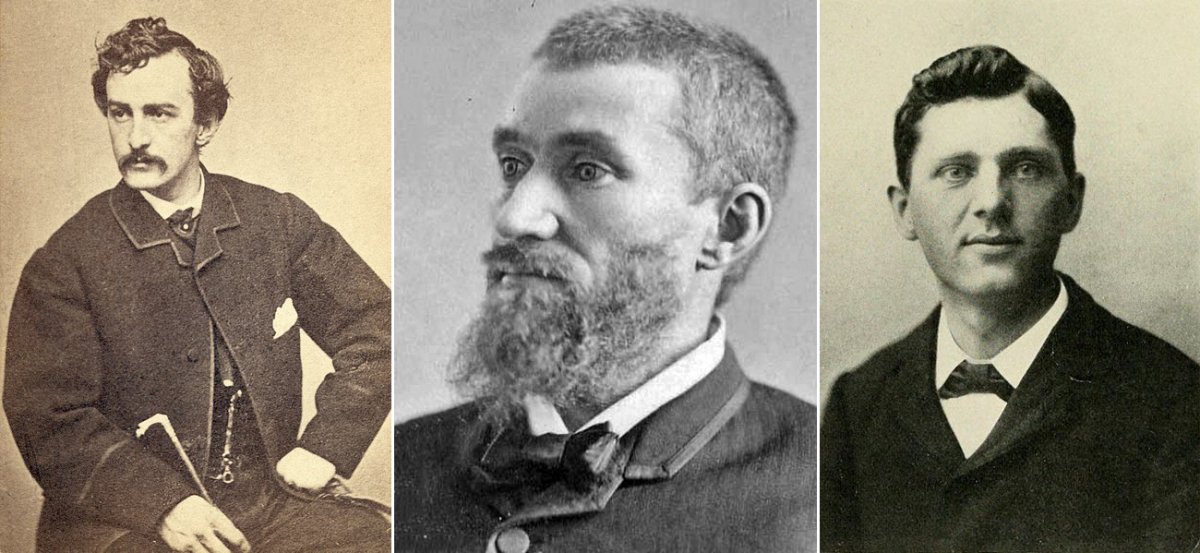

Three of the four successful presidential assassins in American history: John Wilkes Booth, who assassinated President Abraham Lincoln (left); Charles Guiteau, who killed President James Garfield (center); and Leon Czolgosz, who killed William McKinley (right).

While Andrew Lloyd Webber and his fellow mega-musical impresarios brought history to life on stage in increasingly elaborate spectacles, Stephen Sondheim followed a very different approach. His 1990 Off-Broadway show Assassins rejects a linear narrative or traditional plot structure in its depiction of the nine men and women who have tried to kill a U.S. president (four of whom succeeded).

Instead, the musical takes the form of a macabre carnival game, with each of its motley cast of characters taking center stage to explain his or her motivations for their terrible deeds: John Wilkes Booth, who assassinated President Abraham Lincoln; Charles Guiteau, who murdered James A Garfield; Leon Czolgosz, who killed William McKinley; Giuseppe Zangara, who shot at President-elect Franklin D. Roosevelt; Lee Harvey Oswald, who killed John F. Kennedy; Samuel Byck, who attempted to kill Richard M. Nixon; Lynette (Squeaky) Fromme and Sara Jane Moore, both of whom tried to kill Gerald Ford, and John Hinckley, who shot Ronald Reagan.

The unconventional subject matter of Assassins reflected an increasing willingness by musical creators to tackle difficult, upsetting topics that would normally be the realm of non-musical dramas. Historical subjects have allowed creators to experiment with new musical styles, such as in The Capeman, Paul Simon and Nobel Literature Laureate Derek Walcott’s 1998 doo wop musical about a 1959 Puerto Rican gang murder, or The Scottsboro Boys, a 2010 musical about nine African Americans falsely accused of the rape of two white women, which was styled as a modern-day minstrel show.

7. Elisabeth (1992)

Musical theater has expanded far beyond the United States and the United Kingdom. Today, not only are international tours a major source of revenue for Broadway and West End shows, but original musicals are being produced around the world as well. Elisabeth, the most popular German-language musical of all time, was originally produced in Vienna, but it has been translated into seven languages and performed for millions of spectators.

Elisabeth tells the story of Empress Elisabeth of Austria, wife of Emperor Franz Joseph. Beautiful and troubled, Elisabeth was ill-at-ease with her public duties as monarch. Most historical observers agree that she likely suffered from depression and a severe eating disorder.

Despite (or perhaps because of) her deeply unhappy existence, “Sisi” (to use her childhood nickname) is the subject of a vast cultural enterprise. Elisabeth the musical joins the ranks of countless novels, a wildly popular Austrian movie trilogy, and an entire cottage industry of souvenirs throughout Vienna. Librettist Michael Kunze and composer Sylvester Levay’s Elisabeth is a melodrama that embraces our morbid fascination with Sisi head-on.

"Elisabeth, open up my angel," from a 2002 production of Elisabeth, with English subtitles.

The central romance in Elisabeth is actually a love triangle: between Elisabeth, her husband, and Death itself, in the form of a handsome young man. The tragedies that shaped Elisabeth’s life – the loss of one of her daughters in childhood, and her only son’s death by an apparent suicide pact with his mistress – become part of Death’s decades-long seduction of Elisabeth. The show ends, just as Elisabeth’s real life did, with her assassination at the hands of an Italian anarchist…. and with Death, embracing Elisabeth like a lover.

8. Leonardo the Musical: A Portrait of Love (1993)

Leonardo da Vinci's "Mona Lisa" (left); An aerial photograph of the Pacific nation of Nauru (right).

Sometimes, the history behind a musical production overshadows the story being brought to life on stage. This was certainly the case with Leonardo the Musical: A Portrait of Love, a highly fictionalized retelling of the life of Leonardo Da Vinci that imagined the Mona Lisa as the product of a torrid love affair between the great Renaissance artist and polymath and the painting’s subject. Panned by critics and audiences alike, the show closed after only a few weeks on London’s West End in 1993, leaving little mark on the British stage.

Yet, it left a lasting impact some nine thousand miles away, on the tiny Pacific island of Nauru. For decades, Nauru’s largest industry had been phosphate mining, first under its German and Australian colonial rulers, and then as an independent nation. Although phosphate mining generated phenomenal wealth, it caused intense environmental damage to the island, and as the mines began to run out, government officials turned to increasingly outlandish schemes to diversify the island's portfolio.

"Let me Be a Part of Your Life,” from Leonardo the Musical: A Portrait of Love.

Leonardo the Musical was the brainchild of Duke Minks, a former roadie for a 1960s British pop band who had reinvented himself as one of Nauru’s financial advisors. The Nauru government invested $4 million to produce Leonardo the Musical and lost it all. Today, Nauru is almost entirely reliant on foreign aid, with much of the island uninhabitable due to the effects of phosphate mining.

9. Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson (2010) / Hamilton (2015)

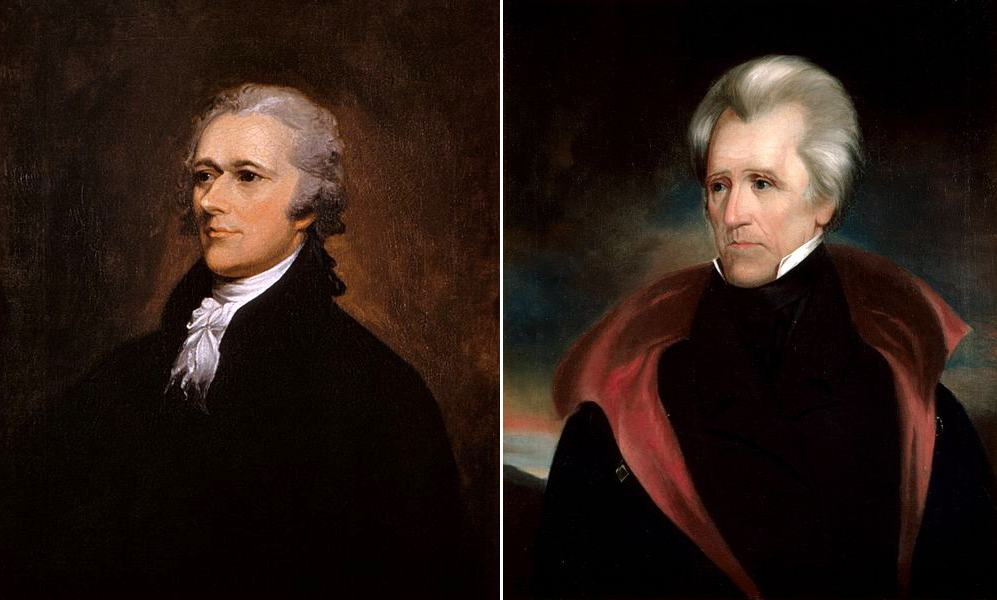

Alexander Hamilton (left); Andrew Jackson (right), both of whom are portrayed quite differently in recent musicals bearing their names.

In the blockbuster musical Hamilton, creator Lin-Manuel Miranda portrayed Founding Father and Federalist Papers author Alexander Hamilton as an immigrant striver, a “bastard, orphan son of a whore and a Scotsman” whose hunger for greatness left a profound influence on the United States before dying in a duel with Aaron Burr in 1804. With a cast composed almost entirely of actors of color and a score that incorporated hip-hop and R&B music alongside traditional show tunes, Hamilton seemed like the quintessential cultural production of the Obama era – particularly given that Miranda first performed a selection from the show at 2009’s White House Poetry Jam.

While Hamilton epitomizes the youthful optimism and diversity of the Obama political project, 2010’s Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson provides the musical soundtrack to the global upsurge in nativist populism of the last decade. With a book by Alex Timbers and music and lyrics by Michael Friedman, Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson is an irreverent account of the rise of America's seventh president, a brash outsider who upended the political establishment of the day with promises to “take back the country” and “take a stand against the elites.”

"Populism, Yea, Yea!” from the original Broadway cast of Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson.

Although the show portrays Jackson as a vibrant, charismatic rock star, it’s far from a hagiography, and doesn’t shy away from the more controversial aspects of Jackson’s record. Indeed, by making Jackson a compelling figure, the show highlights the unsettling fact that most white Americans were complicit in (or at least broadly approving of) the Jackson administration’s expulsion of Native Americans.

10. Newsies (2012)

Young children picking up their newspapers to sell on the streets of New York in 1910.

Traditionally, Broadway has served as a fertile source of musicals to translate to the silver screen. While big-budget movie adaptations still happen, the decline of the movie musical has coincided with a rise in theatrical productions that were adapted from movies.

Newsies is one such Hollywood-to-Broadway hybrid. This rousing real-life tale of child newspaper sellers who went on strike in 1899 for better pay began life as a 1992 live-action movie starring Christian Bale. A box office flop, it acquired a cult following among young theater enthusiasts, and two decades later made its way onto the stage for the first time, with playwright Harvey Fierstein writing a new story to accompany the original music and lyrics by Alan Menken and Jack Feldman.

"The World Will Know," from the 1992 film version of Newsies.

In both versions of Newsies, most of the newsboy characters are invented, but their antagonist was real: Joseph Pulitzer, the publisher of the New York World, who sought to maintain profit margins by raising the prices for his young distributors. The fictionalized strike ends with a timely intervention from Theodore Roosevelt, who convinces the publisher to back down. In reality, however, the newsboys managed to extract concessions that increased their take-home pay without any convenient third-act deus ex machina. At a time when youth activism on issues like gun-control and climate change betrays an unwillingness to wait for older generations to catch up, the radical spontaneity of Newsies's young heroes feels more relevant than ever.