For millennia, dams have played a central role in human life and natural systems. They have served myriad uses for humans, from collecting water for irrigation, drinking, bathing, and leisure, to mitigating flooding, milling grain, stocking fish, and producing energy. The twentieth century in particular saw an unprecedented flurry of dam construction, especially for hydroelectric power. Dams like the Hoover Dam in Nevada and the Three Gorges Dam in China stand as icons of the modern, industrialized world. When the Bonneville Dam opened on the Columbia River in 1937, writer Lewis Mumford hoped hydroelectric power would allow for cheap and sustainable urban development in Oregon but Mumford’s utopian dream never saw fruition. As huge new dams are being built in Brazil and China, while campaigns to decommission dams are gaining traction in the United States (especially in the western U.S.), Origins takes a look at human dams across history to reflect on the many ways that humans have chosen to engineer their rivers and waters.

1. Roman Dams Still in Use

|

| The Cornalvo Dam, near the city of Mérida in Spain. |

The Romans were amazing water engineers. They employed a number of hydrological technologies to divert water for purposes of irrigation, settlement, drinking, bathing, and even recreation. In contrast to other Roman ruins, which now serve as tourist attractions, many Roman dams remain in use to this day, mostly as drinking reservoirs. The Romans erected dams primarily in areas with poor precipitation, such as the Mediterranean basin and Syria, in order to ensure sufficient water for irrigation of crops and drinking water. One of the oldest still in use for drinking water, the Cornalvo dam, can be found a few kilometers from Mérida, in western central Spain. Built between 1 and 2 CE, the dam stands as a remnant of the former Roman provincial capital, which earned it distinction as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1993. At 28 meters it stands just higher than its nearby cousin, the Prosperina dam. The Lake Homs Dam in Syria, built around the same time, continues to supply drinking water to the besieged city of Homs.

2. Nero’s Dams at Subiaco

|

| The Aniene River near Subiaco, Italy. |

Constructed during the reign of the infamous Roman emperor Nero (54-68 CE), the dams at Subiaco (in the province of Rome) sustained pleasure lakes at the ruler’s summer villa. The Subiaco dams were the only examples of large-scale dam technology used by the Romans in Italy. These gravity dams used the weight of their material to halt the flow of water. Other forms of dams, such as arch or buttress dams, use their geometry to resist and divert water pressure. The largest of the Subiaco dams stood as the highest dam in the world until its alleged destruction by clumsy monks in 1305. Located near the Roman capital, the Subiaco dams also served some municipal functions. Scholarship on Roman drinking water suggests that the water quality of Rome’s many aqueducts varied significantly. Most of the water deemed unsuitable for drinking went to irrigation, but in some cases Roman engineers diverted aqueducts from the Aniene River into Nero’s pleasure lakes, which acted as a settling basin.

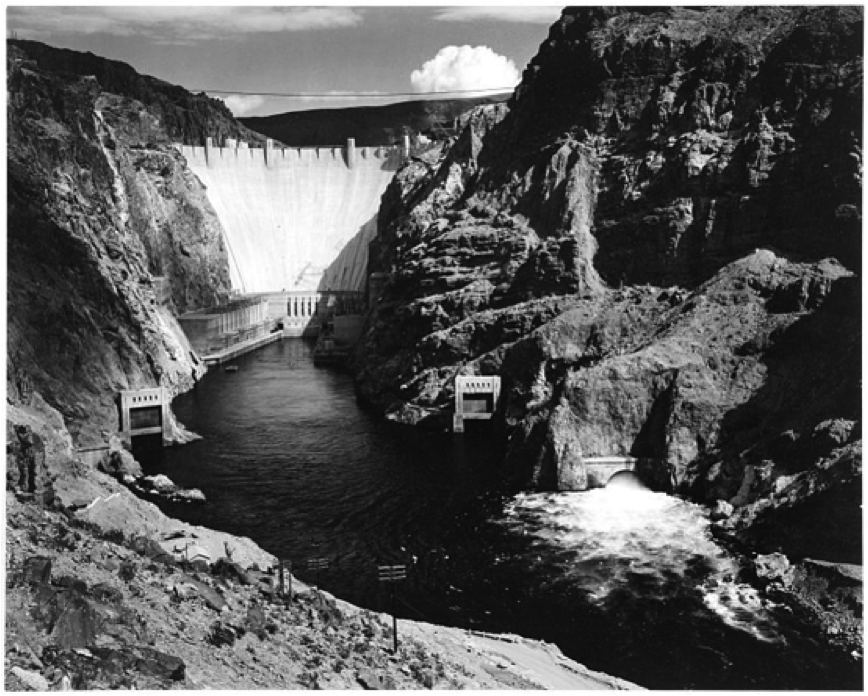

3. Hoover Dam: Hydroelectricity and Water in the U.S. West

|

| Photograph of the Hoover Dam by Ansel Adams from 1942. |

The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (BOR) was founded in 1902, but left its greatest legacy between the 1930s and the 1960s. During that time the Bureau oversaw the construction of more than half of its 340 active dams. In 1928, Congress approved a bid by a consortium of utility companies to construct the Hoover dam on the Colorado River. Upon completion in 1935 the Hoover dam was the largest in the world and one of the largest concrete structures at the time. Its reservoir, Lake Mead, retains the title of largest man-made lake in the United States.

The construction of the Hoover Dam required that the seven states in its basin—Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, Wyoming, Nevada, Arizona, and California—agree to water management standards set by the Colorado River Compact of 1922. Unfortunately, the data used to establish those standards did not reflect actual long-term averages of precipitation. A 2007 study concluded that the negotiation of the compact occurred at a time when the flow of the river was unusually high, 20.2 cubic kilometers per year, compared to a more realistic average of 16.5. As the only water source in a very dry region (what used to be called the “Great American Desert”), the peoples and governments on the Colorado River now struggle mightily to manage with ever-growing water shortfalls.

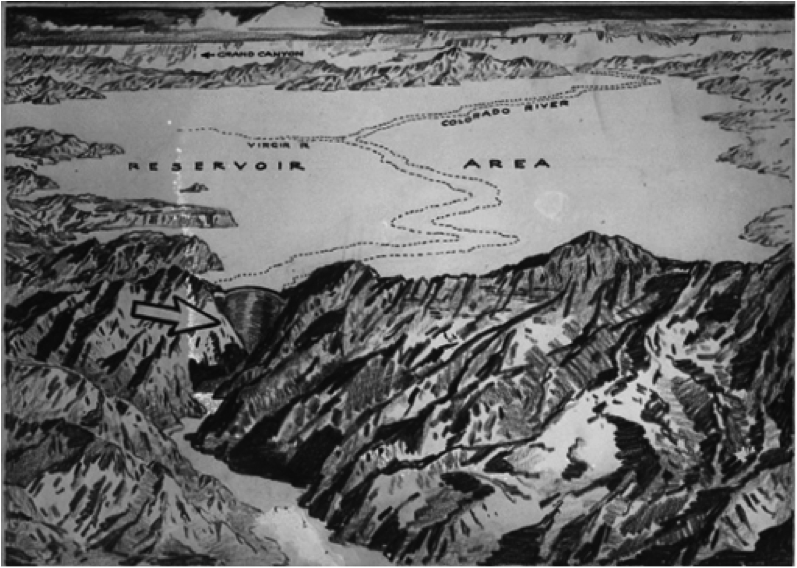

|

| A sketch of the proposed reservoir. |

4. Dam Removal: the Elwha River and Glines Canyon

|

| A photo of the Elwha Dam taken for the Lower Elwha Fisheries office in 2005. |

Many of the dams built by the BOR in the Pacific Northwest have come under harsh criticism for their devastating effect on salmon populations. Between 2012 and 2014 the U.S. National Park Service decommissioned two dams on the Elwha River: the Elwha dam, completed in 1913, and Glines Canyon dam, completed in 1927. The dams produced little electricity and blocked over 70 miles of vital salmon spawning habitat. Costly stunts like the transport of fish by boats up the river and past the dam drove activists to protest against the continued operation of these “deadbeat” dams. (One activist, Mikal Jakubal, famously painted graffiti cracks down the faces of both dams (see photo below)).

The five species of salmon have not been the only motivation for dam removal. In addition, populations of American Shad and Steelhead have had their ecosystems restored by letting rivers run free. The United States Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 has also provided the basis for the removal and cleanup of dams like the Milltown Reservoir in Missoula, Montana, where the buildup of toxic sediment from nearby mines marked the location as a toxic Superfund site.

|

| “Elwha be Free,” with painted on cracks on dam, photo by Mikal Jakubal. |

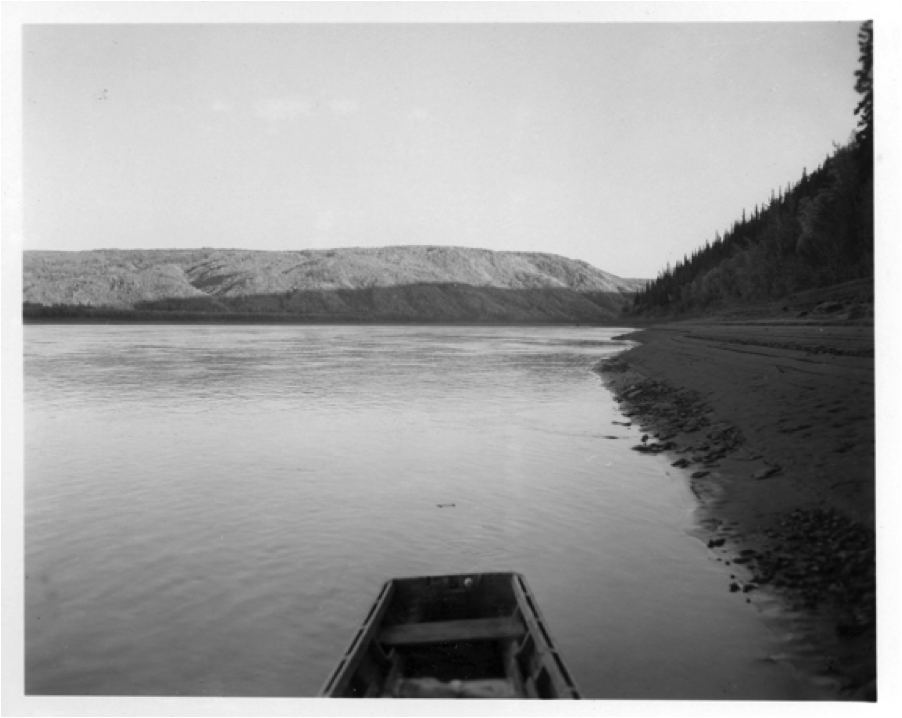

5. Dams not Built: Rampart Dam, Alaska

|

| U.S. Geological Survey photograph of the Rampart Canyon. |

The Rampart Dam in Alaska is perhaps the most famous hydroelectric dam that never existed. Planned and contested between 1944 and 1971, the project, proposed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, aimed to dam the Yukon in central Alaska for hydroelectric power. The reservoir was to be roughly the size of Lake Erie, and would have overtaken Lake Mead as the largest man-made lake in the United States. (Though it would have still been smaller than the lake created by the Kariba dam on the Zambezi river, which was constructed in 1955 and remains the largest man-made lake on earth.)

Opponents argued that the displacement of Native American communities, the project’s cost, and the devastation of the Yukon Flats (one of North America’s most important waterfowl breeding grounds), outweighed the benefits of cheap electricity in a sparsely populated area. The proposed area for the Rampart dam’s reservoir now belongs to the Yukon Flats National Wildlife Sanctuary, established by President Jimmy Carter in 1980.

6. The Politics of Dams: Egypt’s Aswan High Dam

|

| Egypt’s President, Gamal Abdel Nasser, observing the construction of the Aswan Dam. |

Dams are much more than artifacts or markers of man’s industrious might; they also reflect developments in international politics. The Aswan High Dam in Egypt became not only a way to tame the mighty Nile, but also a major issue in the Cold War. When Secretary of State John Foster Dulles announced that the U.S. would not fund the dam’s construction in 1956, he signaled an uneasy relationship between the United States and Egypt, helping to set the stage for the proceeding Suez crisis and the Cold War.

Dams built to tame the Nile in 1889, 1912, and 1933 had all overflowed. After almost two decades of political tension, British and Soviet Engineers completed the Aswan High Dam in 1970. It stands 364 feet tall and generates over 10 billion kilowatts, or about half of Egypt’s power. In exchange for taming the damage of annual floods, farmers have become much more reliant on fertilizers, as silt, no longer dispersed by the Nile’s floods, collects in Lake Nasser.

7. The Ongoing Appeal of Dams: Three Gorges Dam

|

| The Three Gorges Dam in China, photo 2009. |

Even as droughts and erratic weather patterns increasingly challenge the sustainability of reliable hydroelectric power, countries all over the world continue to construct massive dams to meet their energy needs. In 2008, with the opening of the Three Gorges Dam, China saw the completion of a century-long dream to dam the Yangtze River. As power changed hands over the course of China’s turbulent twentieth century, massive projects to dam the Yangtze had captured the attention of the Nationalist government under Chiang Kai-Shek, the Japanese occupation forces during WWII, and even the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation.

Approved by the People’s Republic of China in 1992, the current dam is the most expensive hydroelectric facility ever built and one of the most expensive energy plants, at a cost of roughly $28 billion. In anticipation of even greater energy demands, China continues to plan massive hydroelectric projects. Upon its completion in 2020, the Baihetan dam will rank as one of the largest in the world (along with China’s Three Gorges and Xilodu dams, and the Itaipu and Belo Monte dams in South America).

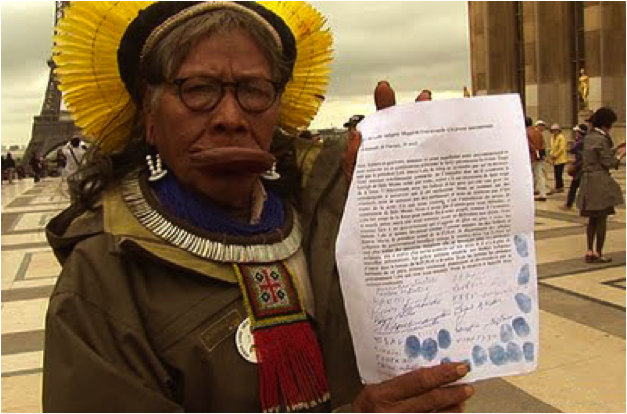

8. Under Construction: Belo Monte Dam in Brazil

Amid controversy, Brazil plans to complete its second largest dam by 2019. With a capacity over 11,000 megawatts, the Belo Monte Dam on the Xingu River (a tributary of the Amazon) in northern Brazil would be among the largest dams in the world. But as Brazil’s economic growth and reliance on hydroelectric energy increase, critics worry about the potential social and ecological repercussions. The dam’s reservoir will flood and change rainforest habitat for hundreds of square miles, displace as many as 20,000 people, and threaten biodiversity of one of the Amazon’s tributaries.

The Belo Monte Dam has also attracted criticism for its production of greenhouse gasses. In spite of Lewis Mumford’s progressive hopes for hydroelectric power, many plants produce more carbon emissions than analogous facilities running on fossil fuels. Plant matter trapped by reservoirs decays anaerobically, which accounts for not only the net carbon produced but also high levels of methane, another significant greenhouse gas.

9. Other Types of Dams: Landslide Dams, Lake Waikaremoana, New Zealand

|

| Lake Waikaremoana, photograph by Michal Klajban. |

Humans can also benefit from the results of geological forces. The three power stations completed on New Zealand’s Lake Waikaremoana between and 1929 and 1948 are unique in that they are the only hydroelectric facilities built on an existing natural dam, which dates back to the creation of the lake by a landslide some 2,200 years ago. The projects to reinforce and utilize the massive natural dam, which at 400 meters dwarfs the Three Gorges Dam, stand as marvels of engineering boldness. The combined hydroelectric facilities produce about 125 megawatts of electricity, using weirs to redirect the lake’s outflow into a useable hydraulic head of over 200 meters.

10. Nature’s Tallest Dam: Usoi Dam, Tajikistan

|

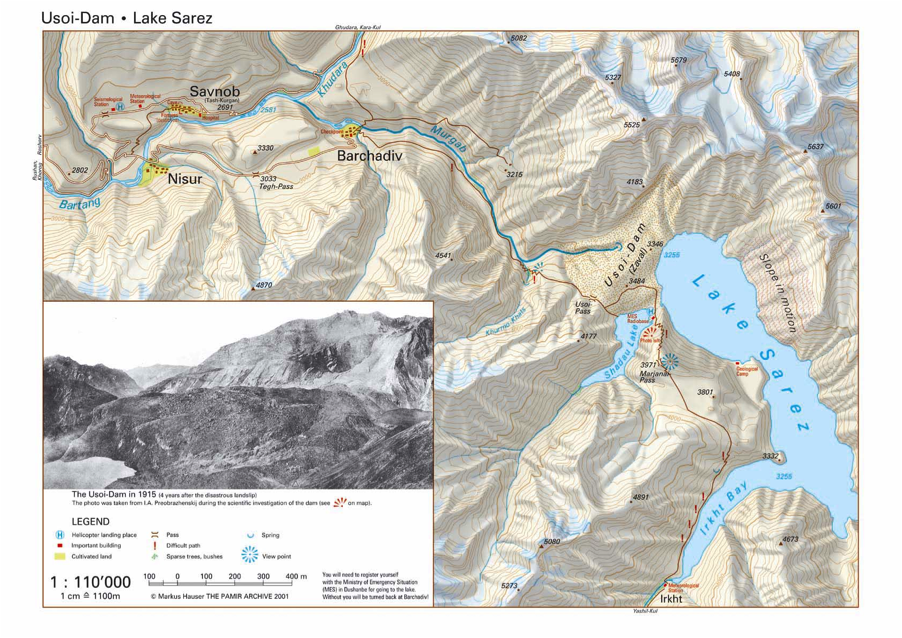

| Map of Lake Sarez and Usoi Dam. |

|

| This photo shows Sarez Lake, the barrier pictured is not Usoi Dam, but rather an earthen division between the larger Sarez Lake, and a smaller body of water. |

In 1911 a massive earthquake formed the Usoi Dam, a natural landslide dam on the Murghab River in Tajikistan. At 567 meters, it is the largest dam on earth. Its reservoir, Sarez Lake, while only a modest 30 meters squared, is unrivaled in its remoteness and beauty at over 10,000 feet above sea level. Unfortunately the dam and its lake have been a cause for concern. Although the World Bank maintained that the Usoi Dam was stable in a 2004 study, many warn that the threat of frequent seismic activity high in the Pamir Mountains will inevitably disrupt the dam, releasing over 16 cubic kilometers of water.

Bonus: Our Fellow Dam Builders, Beavers

|

| A beaver and its dam. |

Beavers remind us that humans are not the only animals who use technology to engineer their environment. Before European settlers arrived to North America, beavers and their dams played a crucial role in river ecology. But as European settlers began to construct their own dams for mills, beavers increasingly became a nuisance, blocking rivers and damaging farms and property with floods. As European settlers trapped valuable beaver fur for global market, they inadvertently transformed the hydrology of North America by removing these talented dam builders from the ecology and releasing water from untended former beaver dams.

With the rebound of beaver populations in the twentieth century, beavers have returned to their role as important ecological actors. Beaver dams help improve water quality and biodiversity through the creation of wetlands and also help curb soil erosion and drought by channeling run-off from streams into ponds.