Decades after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, our boundless fascination with his life and death remains as strong as ever. And the way that Jackie and Jack continue to captivate Americans says as much about how we understand our collective history and ourselves as it does about the tragic couple and their mythic Camelot.

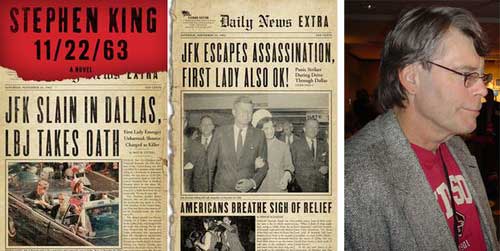

Stephen King’s recent best-selling novel 11/22/63 (2012) tells the story of Jake Epping, a schoolteacher given the chance to travel back in time to the 1960s and stop Kennedy’s assassination. Born a generation after the death of JFK, Jake’s knowledge of the dead president is more history than memory, and yet he takes up the mission when his friend Al, a child of the Baby Boom, is crippled by cancer. Al argues that saving Kennedy would also “save his brother. Save Martin Luther King. Stop the race riots. Stop Vietnam, maybe … Get rid of one wretched waif [Lee Harvey Oswald], buddy, and you could save millions of lives”(69). 11/22/63 positions the death of JFK as a linchpin of the 1960s and an event that resonates beyond those actually alive 50 years ago.

King’s novel joins a massive and ongoing industry of popular novels, movies, stories, plays, and histories that grapple with the tragic events of November 22, 1963, in Dallas. Conservative radio commentator Bill O’Reilly’s best-selling nonfiction book Killing Kennedy: The End of Camelot (authored with Martin Dugard, 2012) comes to life in a docudrama on the National Geographic Channel this month.

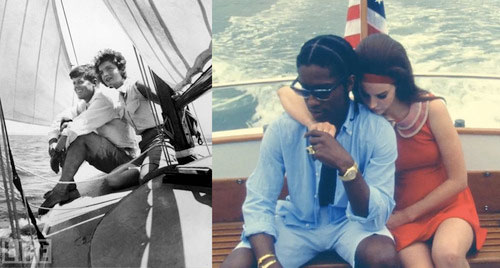

James Marsden plays Kennedy in Lee Daniels’ The Butler (2013), a historical drama about an African American butler working in the White House, and the film Parkland (2013) reimagines the assassination from the perspectives of those on the ground including the Secret Service agents and the doctors who attempted to save Kennedy’s life. Pop singer Lana Del Rey drew controversy in 2012 for releasing a music video that reimagined iconic home movies of Kennedy and his wife by replacing the first couple with Del Rey and rapper A$AP Rocky.

On its 50th anniversary, the assassination of JFK still fascinates us deeply. Popular culture continues to reanimate the tragedy, adding to our collective understanding. It also draws on the shared sense that we were there—even if we were born years or decades later—because of the many images of the shooting we’ve seen, from the grainy images of the Zapruder footage to the high art of Oliver Stone’s 1991 conspiracy film JFK . With their movie star looks, moneyed East Coast pedigrees, and keen fashion sense, JFK and Jackie served as a perfect national fairy tale that played out on the covers of popular magazines.

In the 1960 election campaign, Kennedy’s youthful vitality glimmered into American homes during the first televised presidential debates. His death has come to symbolize the turmoil of the 1960s, a sharp turn from a fantasy of 1950s, white-picket-fence innocence to the race riots, student protests, and social-justice movements that dominated Lyndon B. Johnson’s tenure. In popular culture, JFK’s death stands for promise unfulfilled and serves as the tragic end to an American myth.

Our obsession with Kennedy persists because it was the first national tragedy truly mediated through television and the “live” moving image. In an era before the Internet or twenty-four-hour news channels, news of the assassination traveled so quickly that half of all Americans heard about it before the president was pronounced dead just 30 minutes after the shooting. And within two hours, 92% had heard the news.

Over the next four days most Americans consumed the same set of images, as all major broadcast networks abandoned commercial programming and exclusively covered the aftermath, Johnson’s swearing in as the new president, and the public funeral. This round-the-clock coverage signaled the beginning of our current collective response to tragedy, our obsessive need for up-to-the-moment coverage and deeply felt personal connection to televised victims.

While there are no professional films of Kennedy’s death itself, the iconic filmic representation of JFK’s murder remains the 26 seconds shot by amateur cameraman and dressmaker Abraham Zapruder. For many of us, this brief clip, with Jackie Kennedy frantically climbing down the back of the car, has become part of our collective memory of this tragedy. Character actor Paul Giamatti portrays Zapruder one of the key figures in Parkland.

Art historian David Lubin calls the Zapruder film “the saddest movie ever made.” According to Lubin’s history of the Kennedys in pop culture, Life magazine purchased the film from Zapruder and published blurred black-and-white stills in their November 29, 1963 issue. Color enlargements appeared in the magazine’s pages several times in the early 1960s, but the moving images began circulating in bootlegged film prints in the late 1960s.

The Zapruder film entered the public domain in 1975 through national broadcast on Geraldo Rivera’s Goodnight America and has become a staple of documentaries, museums, and the Internet. Even watching the Zapruder film on YouTube today can elicit chills—the combined weight of the historical moment, of pathos, of encountering the dead, of seeing the promise of youth snuffed out.