There were only two kinds of people in most of early-modern Europe to whom an ordinary person could turn for help when confronted with life’s more trying circumstances. One was the local priest, who was unlikely to offer more than prayers. The other was a magician.

In the few large cities, a wealthy client could go to a learned astrologer or necromancer for answers to her or his problems. However, in the vast majority of Europe, which was rural, the local magician was a “cunning woman” or “cunning man,” a low-level wizard who had picked up some simple folk medicine and magical techniques alleged to ease childbirth or illness, find lost objects, expose thieves, predict seasonal weather, and foment love.

If you happened to live in Scotland, in the region east of Edinburgh, around the villages of Musselburgh, North Berwick, and Haddington in the 1570s and 1580s, and you had need of such services, you might have sought out a cunning woman named Agnes Sampson.

She had a wide clientele from all levels of society and was well known locally as the “Wise Wife of Keith.” Sampson knew methods for healing wounds, delivering babies safely, healing man and beast, predicting storms, and counteracting the maleficent spells of witches.

In 1590, Agnes Sampson was arrested for attempting to kill Scotland’s King James VI, and his bride, Princess Anne of Denmark, using witchcraft. She was executed in January of 1591.

Her story and gruesome end demand that we ask how Sampson transformed in the eyes of her contemporaries from a beloved local healer into a witch.

The fascinating story of Agnes Sampson and the other “North Berwick Witches” tried with her is exceptionally complex, involving politics, religion, magic, and conspiracy theories.

It is particularly significant for historians because the same King James VI of Scotland who was personally involved in Agnes Sampson’s trial would soon become king of England, as James I, where he established the Stuart monarchy, commissioned the King James Bible, wrote an important treatise of witchcraft, and shared the spotlight in London with William Shakespeare.

Our story really begins in 1589, when the Earl of Bothwell joined a group planning a rebellion against King James. The rebellion was rapidly quashed, but James remained, justifiably, in constant fear of further rebellion.

This was a particularly perilous time because his coffers were depleted by years of famine and poor financial management. It was now, nevertheless, that James, who was 23 years old, opened negotiations to marry Princess Anne of Denmark.

James’ official marriage to Anne was accomplished in absentia, in August of 1589. In September, Anne set sail from Copenhagen for Scotland, where James eagerly awaited her arrival, but terrible storms and leaks in her ship held up her fleet.

In October, news finally reached Scotland that the queen was stranded in Norway. James decided to travel to Norway to meet his bride. He was slowed by contrary winds but arrived in November and was officially wedded to Anne in Oslo. The royal couple and their retinue then went to Denmark to celebrate. They finally traveled home to Scotland in April 1590, despite more dangerous storms.

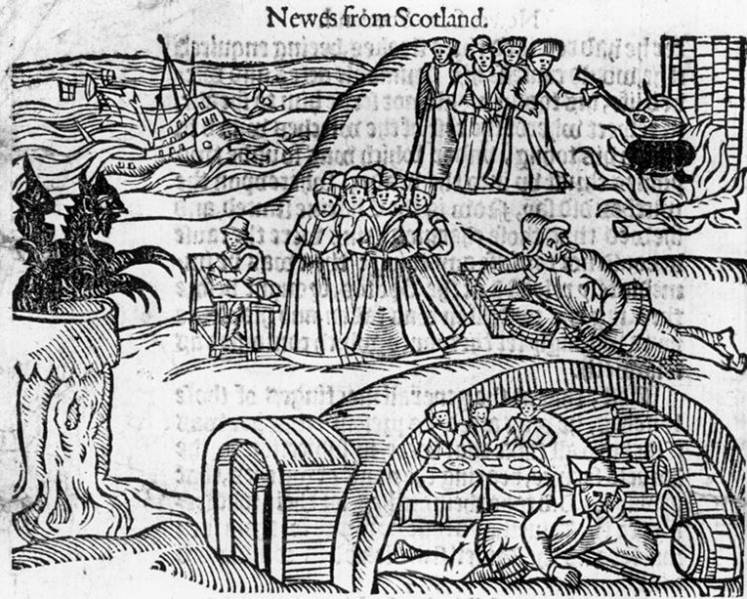

What happened next is difficult to discern with any precision and I will do my best to reconstruct the story. There are two sources: a pamphlet, called News from Scotland, and fragmentary trial records. The pamphlet is unreliable as all such publications of the day are, and the trial records are partial and difficult to understand at times.

King James had a particular friend who lived near the Firth of Forth, named David Seton. According to the pamphlet, Seton’s maidservant, Geillis Duncan, was a successful cunning woman.

Seton, suspicious about the source of her abilities, questioned her, then tortured her, and finally searched for a “witch’s mark” allegedly made by the Devil on his minions. Such a mark being found, Geillis confessed to attending a witches’ sabbath—a party of witches with the Devil—where she agreed to serve the Evil One.

She also named other witches, among whom was her fellow cunning-woman, Agnes Sampson.

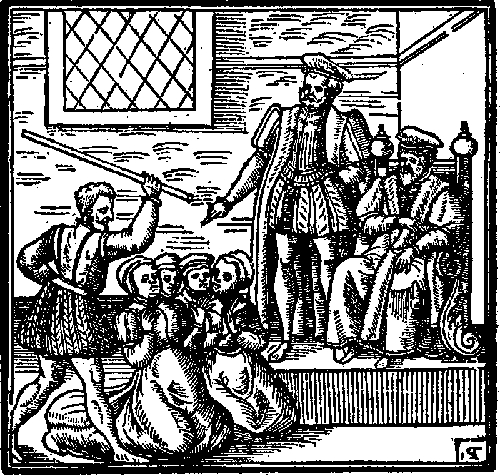

Sampson was arrested, questioned, and tortured as well. It was again, according to the pamphlet, the discovery of a witch’s mark that finally caused her to break down and confess. Her next interview was in front of the king and his council, where she described events at the witches’ sabbath in detail, including the means of compacting with the Devil there.

In her confession before the king, she proved her powers by reciting for him verbatim the conversation that had passed between him and Queen Anne in the privacy of their bedchamber on their wedding night, leaving James astonished.

The substance of her confession was that the Devil had a particular hatred of King James, whom he considered his greatest enemy, and thus deputized Sampson and her fellow-witches to kill him.

This was allegedly to be accomplished by “christening” a cat, tying pieces of a human corpse to it, and throwing the cat into the sea near Leith in Scotland. This act was the cause of the enormous storms that almost destroyed the royal couple’s fleets on multiple occasions and was supposed to kill them. The core of Agnes Sampson’s devilish treachery was, then, an amalgamation of religious, political, and magical elements.

It was not uncommon for a cunning woman like Agnes Sampson to find herself accused of witchcraft during the early modern witch hunts.

Anyone understood to have the magical knowledge to heal and help people would certainly have the power to damage or injure them as well, should she so desire. In addition, however, theologians in this period increasingly insisted that the use of any form of magic demanded a pact with a demon or devil and thus constituted heresy against Christianity.

The European witch hunts lasted roughly three centuries. Nearly half of those who were tried for the crime of witchcraft were executed. In all such cases “witchcraft” was a term that covered many complicated social and political issues, just like the case of Agnes Sampson.

![]()

Learn More:

On cunning men and women, see Tabitha Stanmore, Cunning Folk: Life in the Era of Practical Magic (London: Bloomsbury, 2024).

On the “North Berwick witches,” see Lawrence Normand and Gareth Roberts, Witchcraft in Early Modern Scotland (Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 1988).

On the European witch hunts, see Brian P. Levack, The Witch Hunt in Early Modern Europe, 4th ed. (London: Routledge, 2016).