Who owns the art from the non-Western world that fills the galleries of Western museums? That has become the most vexing question facing museums in the United States and Europe today. This month historian Sarah Van Beurden examines this issue by looking at the debates over material taken from Africa during the period of European colonialism. As she explains, what to repatriate and under what terms are complicated problems.

In 1978, Amadou-Mahtar M’Bow, the Senegalese director of UNESCO, called upon the global public to consider restitution of cultural heritage removed during colonialism. He argued that being robbed of cultural objects, human remains, and art equaled the removal of collective memory and a sense of self. He called for the creation of bilateral agreements to enable the return of heritage, but also pointed out the responsibility of individual cultural institutions in the Global North to share collections.

Ironically, it was the shortcomings of a UNESCO convention that brought M’Bow to this position. With the 1970 Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, UNESCO attempted to address the issue of the loss of cultural heritage in formerly colonized countries.

Many former colonial powers objected, however, and the final text of the convention addressed continuing loss through illegal art trade, but was explicitly not applicable to heritage removed before 1970. In other words, its regulations did not allow for a frank discussion of colonial collecting or plundering, leading to M’Bow’s speech. The issue remains unresolved.

Fast forward to 2017.

French president Emmanuel Macron, in a speech to university students in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, suggested that in the coming five years “conditions be put in place for the temporary or definitive restitution” of African cultural heritage.

He subsequently commissioned Senegalese academic Felwine Sarr and French art historian Bénédicte Savoy to write a report on the issue. The report The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage (2018) is now widely seen as the starting point of restitution debates. But African nations and the African diaspora have been organizing around the subject for years, even if this report has inspired a string of other national initiatives in Europe.

What accounts for the renewed interest in restitution of colonial collections?

One reason is that, despite decades of demands, the issue has never been properly addressed. A second aspect is the role that the growing African diaspora communities have played in drawing attention to the often highly problematic origin histories of colonial museum collections in recent years.

A third element, shifting global relations, also contributes. Cultural politics—like the restitution debates—provide a comparatively easy avenue to strengthen ties, both to new or growing constituencies in the Global North and to African nations. The latter’s ties to former colonizing countries are weakening significantly in the context of resource and investment agreements with, for example, Asian countries.

Finally, generational changes also play a real role in opening up conversations around decolonization in Europe, since allegiances to previous generations involved in the colonial project are diminishing.

Colonialism and Plunder

The plunder of cultural objects, human remains, art, and artifacts has long created conflict, and its consequences pervade the museum landscape in the Global North. Witness Greece’s long crusade for the return of the Elgin Marbles, housed at the British Museum. Or the long and continuing efforts to return Nazi-looted art to its rightful owners.

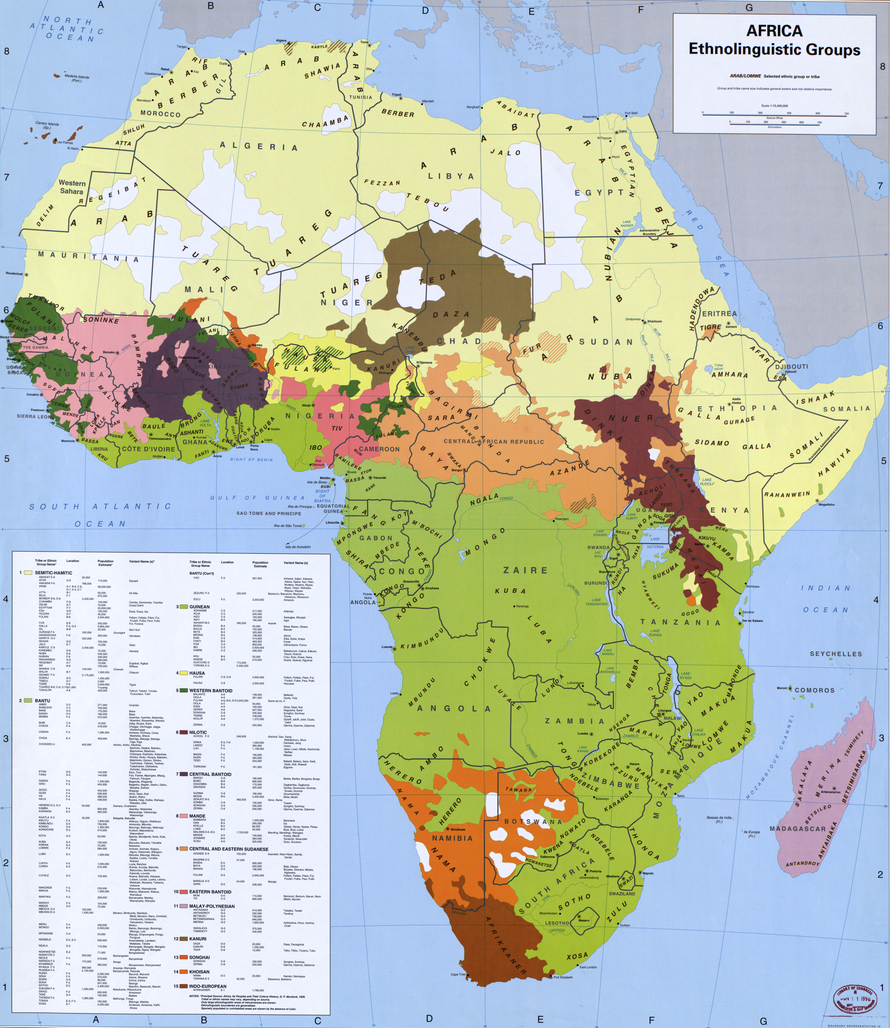

The debates about repatriating African cultural heritage differ in both scale and access: the collections in the Global North are large, while much less moveable, material cultural heritage remains on the African continent. This causes concerns about access of communities and countries to knowledge about their past.

In addition, colonialism shaped the global power structures of today. These effects are visible in continued and large-scale power imbalances, complicating African countries and communities’ abilities to put pressure on governments and cultural institutions in the Global North.

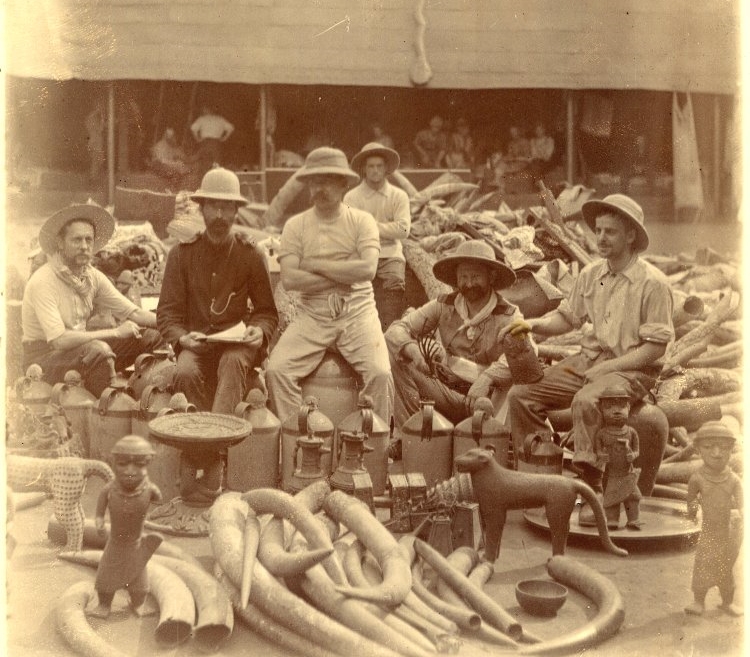

“Collecting” is a euphemism that covers a broad swath of practices in the colonial context. Collecting, in this sense, could involve soldiers, missionaries, colonial administrators, African intermediaries, tourists, and others.

Collectors’ motivations were diverse: sometimes removing objects was motivated by a show of power, curiosity, religious purposes, and so forth. Often collected objects played important roles in the promotion of empire, illustrating the so-called primitiveness of African peoples, thus justifying the need for a colonial “civilizing mission.”

Some of the objects were violently plundered during the conquest and “pacification” of colonies by European military forces.

The best known example is the plunder of the capital of the kingdom of Benin in 1897 by a British “punitive” expedition, during which the now famous Benin bronzes were removed from the royal court. The bronzes were military trophies and eventually became prestigious museum objects.

Events like these—both large and small—were part and parcel of colonialism across the continent in an ongoing exercise of power meant to destabilize African communities. Legal procedures sometimes also led to the confiscation of objects used for so-called “subversive” practices.

Missionaries were another group often involved in the collection or destruction of objects. At times, they destroyed objects or removed them in order to use them for academic study or scientific research. Many missionaries believed that an increased understanding of African cultures would lead to a more effective Christianization. The process of conversion sometimes also led African communities and peoples themselves to surrender objects.

Scientists might have ethnographic interests, but some missionaries surmised that better insight into local customs would lead to a more efficient colonialism. Knowledge was power, and knowledge came from cultural objects.

As colonial administrations grew, so did the scale on which collecting happened. And as the demand for objects increased, so did commercial networks. A market in African art grew in tandem with colonialism. In some cases, renowned sculptors, weavers, and others started producing both for local use as well as for sale to outsiders. The nature of commercial transactions thus varied greatly; some were the result of pressure, others occurred upon African initiative.

These diverse origin stories of collections often complicate the debates about return. Attitudes about restitution are shaped by different interpretations of what constitutes looting and colonial violence in the first place. Although cases such as the Benin plunder are clear-cut, much less agreement exists about other cases, such as when objects were purchased or given.

Many sculptors, for example, sold their work to both local and international patrons. Such a transaction is not the same as a sale under conditions of duress. However, colonialism created such fundamental inequalities that even seemingly neutral transactions might not have been so.

From the 1930s on, conservation and protection of African indigenous cultures slowly became an integral part of colonialism. A sense of custodianship over African cultures came to permeate colonial policies, replacing some of the earlier emphasis on the erasure or destruction of local cultures in the context of the “civilizing” mission.

An important element in this evolution was the growing acceptance of certain objects as “art,” which also impacted their appreciation as heritage. Although certain African objects always had an aesthetic appeal for western audiences, the twentieth century saw a significant broadening of the objects included in the category of African art, an evolution pushed in particular by Modernist painters and sculptors’ interest in African art.

By lifting the objects away from their origin and putting them into the pantheon of art, it became the responsibility of the European states to protect the collections in the west, which were now economically valuable. The impact of this process extended into colonial policies directed at the preservation of arts and cultures in the colonies.

African Demands

We know that even during the colonial era, there were demands for the return of objects that had been looted, with the aim of returning them to their original use.

A good example is the 1878 case of a statue taken during an armed attack by Alexandre Delcommune, a trader in what later became Congo. Almost immediately, local chiefs asked for its return, to no effect.

The independence era (the late 1950s and 1960s) was a catalyst for debates about restitution. Were African museum collections in Europe to be considered as resources for the building of cultural sovereignty in newly independent countries? Should their automatic return be a part of decolonization? What about museum institutions in Europe that had been built with profits from the colonies?

While all these questions were raised publicly in the context of decolonization, they continue to animate discussions today.

Although official demands for repatriation of objects were few in the 1960s, debates around the issue grew. Most independence negotiations focused on more urgent and immediate political and economic matters, but the question of African art collections hovered near and often was raised behind the scenes.

In some cases, there were symbolic “gifts,” such as an Ashanti stool that the United Kingdom returned to newly independent Ghana in 1957. These types of returns continued to occur occasionally over the years.

However, when Nigeria asked the UK for the restitution of the Benin ivory mask that graced the poster for the 1977 FESTAC festival, the British Museum refused. The museum argued that the mask was too fragile and that different conservation conditions would damage it. However, the museum had, in the 1950s, sold Nigeria a number of Benin objects to raise money for other acquisitions.

Generally, it was not a return to their original purposes that was envisioned for the objects and collections, but rather their use as national symbols and museum and art objects. The conservation of the latter had become intricately tied to assumptions about responsible rule in the late colonial period. With the advent of decolonization, these collections had acquired meaning as the national heritage of newly independent African nations.

Internationalized Debates

World War II served as a watershed moment for the emergence of international agreements about cultural heritage. The Hague Convention and protocol of 1954 (the Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict) was conceived in the aftermath of Nazi art looting and gave shape to the idea that cultural property ought to be protected from wartime destruction and maintained in its culture of origin.

Heritage protection had thus been the provenance of international organizations for decades by the time decolonization swept the African continent.

International protocols for the protection of cultural property and heritage, however, were inadequate to navigate discussions about objects moved during colonial rule. With increased representation in international organizations, newly independent countries turned to the path of international regulations to address the issue of colonial collections. But these had only limited effects.

The 1970 UNESCO convention tried to put a lid on the issue rather than addressing it. While a preliminary draft of the convention did mention the issues of restitution of property removed before 1970, many former colonial powers objected, and the final text was explicitly non-retroactive.

Widespread dissatisfaction with the 1970 Convention among former colonies resulted in an increased number of initiatives that pushed back against the limitations of the convention. For example, the Conference of Heads of State or Government of Non-aligned Countries cast the rights of states to recover looted art as related to the Universal Declaration on Human Rights.

Zairian leader Mobutu Sese Seko, in a 1973 speech to the United Nations Assembly, publicly accused former colonizing countries of “colonial pillage.” He demanded cultural restitution by emphasizing the importance of the possession of a national heritage for the future of new nations.

Individual demands and attempts at bilateral negotiations also increased steadily during the 1970s.

Ekpo Eyo, head of the Nigerian Antiquities Service, took a leading role. After a 1971 ICOM resolution he fought for, which called on European and other museums to help establish African counterparts, did not have the desired effect, he turned to direct conversations with museum and heritage institutions in Europe, especially Germany, which proved to be a more willing partner than the UK. Ultimately, though, these conversations led nowhere.

Numerous conferences, workshops, and dialogues, often with either ICOM or UNESCO involvement, followed, to little concrete effect. Between 1976 and 1981, Belgium returned 114 objects to Zaire, but only after the latter explicitly distanced itself from the term restitution and instead accepted the Belgians’ preferred way of describing the return: as a gift.

This example helps us understand some of the deeper tensions underlying these debates: more than the possession of objects, they were about a condemnation of the colonial past, the very past that had given shape to the collections under debate.

Counterarguments?

While the 1970s saw an increase in calls for restitution, they also saw an increase in arguments against restitution. These can be roughly divided into three categories: universalism-based arguments, preservation-based arguments, and legal arguments.

The first emphasized that global access to universal heritage is necessary and should outweigh national or community rights to heritage. Often, these arguments betrayed their bias, since they were constructed around universal access for an audience in the Global North, not the audiences in the Global South.

A second category of arguments revolved around the conservation of collections, prioritizing the latter over accessibility. These are built upon the assumption that museum infrastructure in Africa was de facto inferior to that in Europe or America.

This argument ignored the colonial origins of the underdevelopment of this infrastructure and understated postcolonial investments in numerous cultural infrastructures across the continent. It also ignored the poor conditions of conservation and thefts in some museums in the Global North. The storage rooms of the former Ethnological Museum of Berlin have come under fire for inadequate conditions, for example.

Finally, legally oriented arguments were frequently used against restitution. From a legal perspective, a number of large collections of African objects were (and are) considered national state-owned patrimony, presumed to be inalienable. In addition, museums frequently defended their holdings as legally acquired (for example through donations), thereby distancing themselves from the acts and people associated with their removal from the continent.

Another related argument was based on the assertion that the removal of objects from colonial Africa did not occur in breach of any laws at the time of their removal. Such arguments of course neglected to account for the fact that laws are products of their time, rather than neutral instruments.

Remarkably, despite a growing body of critical thought around colonialism and its long-term effects, it is striking how similar the counterarguments against restitution are today to those that circulated in 1970s.

No Easy Answers

What on the surface appears to be an easily resolvable issue becomes quite complicated upon closer inspection. From a moral imperative there is an easy answer to these debates: access to one’s heritage is by now recognized as a universal value. Undoing empire through the return of cultural heritage, however, has proven to be a complicated proposal.

Myriad initiatives have proliferated across Europe; guidelines for colonial collections (Germany, Netherlands, Belgium), proposed laws for restitution (France, Belgium), museum cooperation initiatives, expert panels (Austria), and even returned human remains and objects (to South Africa, Nigeria, Benin, for example.)

Although together they represent change, a new set of problems has emerged. For one, many of the decisions about guidelines and procedures are currently made in the Global North. Despite the best intentions, such an approach risks reproducing colonial relations.

Frequently, provenance research—detailing the origins of objects and their chain of ownership—is seen as a potential avenue for resolving restitution debates. The assumption is that more research into colonial archives will reveal information about the exact origin of objects and how they were removed.

This assumption rests upon confidence in colonial sources that they often do not deserve. While sometimes we can find information in, for example, field notes or military diaries, for many objects this kind of information is not available.

In addition, colonial archives were created from the colonizer’s perspective and with the particular goal of documenting and administering the colonial project. These archives provide only one among multiple possible perspectives on the removal of objects and human remains.

One solution to this problem is to widen provenance research practices to include more oral histories and memories from communities of origin. Regardless, provenance research will not lead us to conclusive answers about every African object held by a museum in the Global North. Making restitution procedures reliant on this kind of research, then, runs the risk of reproducing the very views that shaped colonial archives.

This is not to say that provenance research does not have its value. It certainly does, and the results (or lack thereof) can be used effectively in exhibition practices in the Global North that raise awareness about the origins of these collections with audiences there. Some restitution policies, therefore, acknowledge the need for different pathways to restitution, based on the communal or spiritual value of an object, for example.

A final thorny issue is to whom objects should be returned? Almost all currently proposed procedures envision state-to-state interactions, thereby leaving aside individual families, communities, or cultures of origin. (These are generally understood to be the communities that produced and/or originally used the objects.)

Cultural communities do not necessarily align with contemporary nation-states, however. Nor do they necessarily live in harmony with the states in which they are located, or they might not agree with them on how and where objects should be cared for.

Neither do essentializing ideas about identity properly take into account cultural change over time. In other words, communities of the past don’t always easily correspond to communities of the present.

Thus, while contacts with state institutions and museums in Africa are important, effective restitution policies also need to look beyond these and engage other communities in reciprocal, collaborative efforts around heritage. These can take the form of digital restitutions or traveling exhibitions, or projects centered around oral testimonies about cultural heritage, for example.

Negotiating A Future

In short, while the issues of colonial collections themselves are deeply embedded in the colonial past, many of the obstacles to a contemporary resolution also are products of the impact of European colonialism in Africa.

We should be mindful of the fact that, in evaluating the colonial past, debates around the restitution of colonial collections also build relations in the present and for the future. In this sense, the current debates about the return of African collections are part and parcel of a broader set of shifting global relations that are still shaped by the aftermath of European colonialism in Africa.

Dan Hicks, The Brutish Museums. The Benin Bronzes, Cultural Violence, and Cultural Restitution. Pluto Press, 2020.

Kwame Opoku, modernghana.com

Bénédicte Savoy, Africa’s Struggle for Its Art: History of a Postcolonial Defeat. Princeton University Press, 2022.

Jos Van Beurden (no relation to the author) Treasures in Trusted Hands. Negotiating the Future of Colonial Cultural Objects. Sidestone Press, 2017.

Sarah Van Beurden, Authentically African. Arts and the Transnational Politics of Congolese Culture. Ohio University Press, 2015.