March 3, 1857 marked the unofficial beginning of the so-called Second Opium War (officially 1856-1860), a conflict that not only forced that narcotic drug deep into China’s politics, public health, and economics but also cemented the country’s status as both a prize and a battleground for Euro-American imperialist powers.

The conflict’s origins trace back to the late eighteenth century, when Great Britain’s acute trade imbalance with China, then under the rule of the Qing dynasty, left it scrambling to access that nation’s porcelains, silks, and luxury goods but unable to sell in return the goods generated by its nascent industrial revolution.

A British trade mission was famously rebuffed by the Qianlong emperor (r. 1735-1796), who declared, “Our celestial empire possesses all things in abundance and lacks no product within its borders. There is therefore no need to import the manufactures of barbarians in exchange for our own products.”

Unwilling to accept an economic playing field tipped in China’s favor, Great Britain found a solution in the latent demand for opium in China. Over the course of the early nineteenth century, British traders exported it in skyrocketing quantities in open defiance of Qing laws prohibiting the drug.

After one Chinese trade commissioner captured and publicly destroyed British opium stocks, Queen Victoria’s government sent warships to China, resulting in what became known as the First Opium War of 1839-1842.

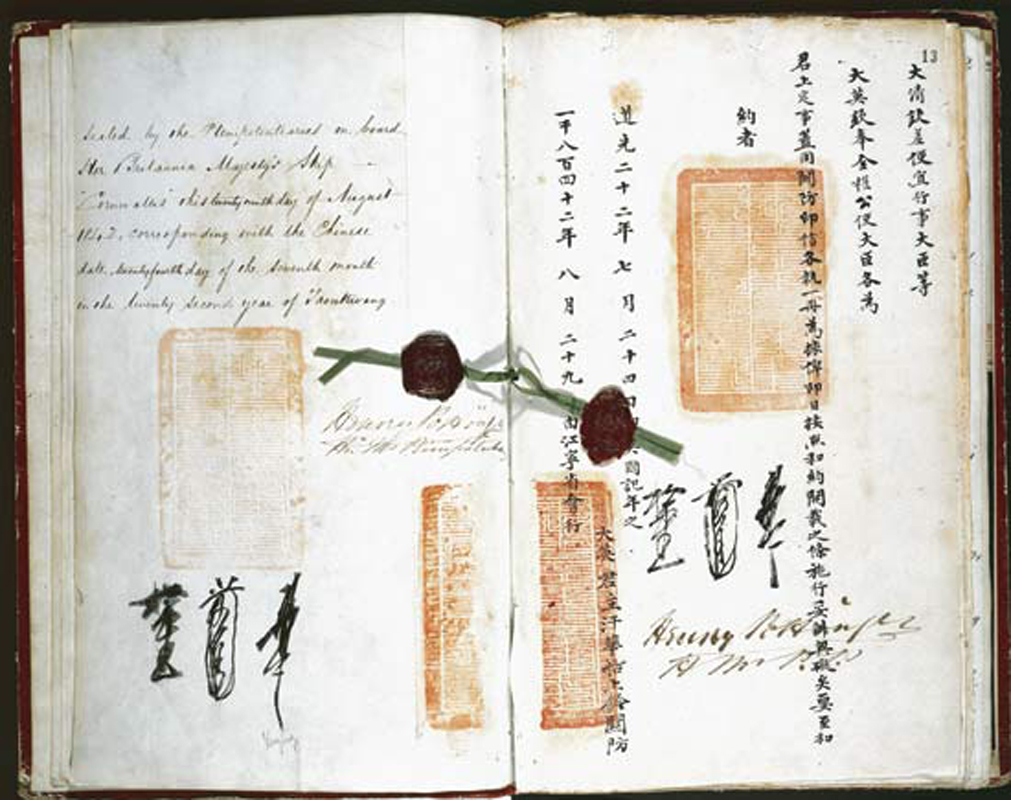

Ultimately, the Treaty of Nanjing (1842) formalized China’s defeat with a series of humiliating provisions, including the payment of an indemnity and the cession of Hong Kong Island to the British. The Qing court also agreed to open five ports to foreign trade, marking the end of its traditional policy of non-engagement with the West.

The First Opium War established China’s importance to the Euro-American imperialist powers and laid the groundwork for the next collision, which erupted just over a decade later, on March 3, 1857. Although fighting had already begun some months earlier, on this date, the British Parliament dissolved over disagreements regarding the proper course of action, reconvening a year later with a stronger pro-war majority.

In the most well-known phase of this Second Opium War, European troops looted and demolished the Summer Palace, an eighteenth-century retreat the Qing court typically occupied during the warmest part of the year.

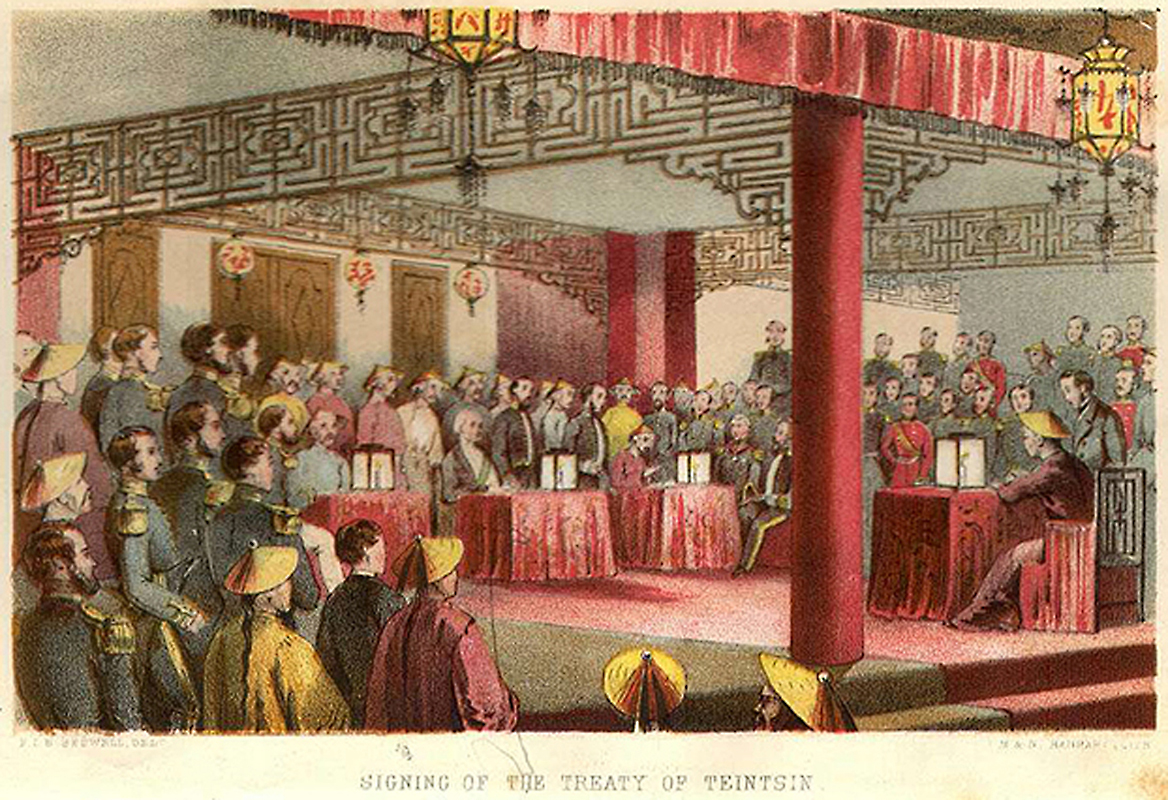

The Second Opium War resulted in the Treaty of Tianjin (1858), which imposed another indemnity on China, opened ten additional ports to foreign trade, allowed British, French, Russian, and American representatives to establish a diplomatic presence in China’s capital, Beijing, and permitted foreigners to sail and settle freely in the Chinese interior.

In the wake of this settlement, China legalized the trade and consumption of opium, setting the stage for the spread of opium smoking throughout the population. Historians debate the relative harms of the drug from the standpoints of public health and fiscal stability, but there is no question that the struggle to rid China of opium was a major social initiative and policy goal of all political contenders and regimes of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Despite its wide-ranging impacts on Chinese politics, public health, and international relations in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, observers then and now have seldom paid much attention to the Second Opium War.

In contrast to the First Opium War, which forms the subject of an exhaustive body of award-winning scholarly and popular literature, the most recent major English-language book to tackle the Second Opium War appeared more than two decades ago. When the Second Opium War has been remembered, its meaning and legacy has often been twisted.

At the time, it represented only another flashpoint of China’s so-called Century of Humiliation (1842-1945) at the hands of the Western powers. The Treaty of Tianjin was but one of many unequal agreements that the imperialist states of Europe and America imposed.

From the perspective of the European belligerents, the resulting legalization of the opium trade changed little, as they had already proven their willingness to defy Chinese law in pursuit of profit. In fact, the conflict coincided with ventures they deemed far more important to their imperial interests, including the Crimean War (1853-1856), Anglo-Persian War (1856-1857), and the Sepoy Rebellion (1857).

More recently, some historians of China have regarded the Second Opium War as a relatively minor event next to other late nineteenth-century natural and human catastrophes, such as the Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864) that resulted in the death of approximately twenty million people.

For one thing, there has been a tendency to write opium out of the story entirely, thereby obscuring (and absolving) the central role of Western imperialism. In the twentieth century, for example, historians sometimes referred to it simply as the “Arrow War”—referencing a British ship seized by China on suspicion of piracy—reducing its complex causes to only its precipitating event.

Frequently-used terms like the “Second Anglo-Chinese War” and “Second Sino-British War” have also conveyed the impression that it was incited less by Western states’ deliberate drugging of China in the name of profit than by a minor rogue ship or breakdown of relations between sovereign states. Worse still, some historians have even labeled the war the “Anglo-French expedition to China,” which erases the reality of Western hostility altogether.

One consequence of the tendency to minimize the importance of the Second Opium War has been the periodic repurposing of its name to describe other events entirely. In the 1950s, for example, observers of communist China described Chairman Mao Zedong’s campaign to eradicate narcotics from Chinese society as a “Second Opium War.”

Today, reporters, journalists, and others occasionally use the term to refer to the export of fentanyl and other synthetic painkillers from China to the United States—a practice implicated in the surging opioid epidemic. The characterization of this traffic as a “Second Opium War” inverts the directionality of the nineteenth-century illegal drug trade. It mistakenly implies a balancing of the scales of historical justice: having been the victim of smuggling on the part of great powers of the West in the nineteenth century, China is represented as the origin of some of the most lethal mind-altering substances in circulation today.

Such careless misuse of history is a powerful argument for recalling the events of the Second Opium War of 1856-1860 and reflecting on the true nature of their causes and legacies.