On January 20, 1986, the United States observed Martin Luther King Jr. Day for the first time.

Yet the meaning of the moment was unsettled.

In Atlanta, the city of King’s birth, people gathered to honor his life of activism. Elsewhere, some states refused to recognize the holiday or diminished it by linking it to Confederate commemorations.

Federal recognition had finally arrived, but acceptance had not, a disconnect that reflected a deep and long-standing resistance to the political and moral challenge King posed.

The history of Martin Luther King Jr. Day reveals how determined the nation was—and in many ways still is—to avoid reckoning with what King actually demanded: an honest confrontation with racism, inequality, militarism, and the unfinished work of American democracy.

A Proposal the Nation Was Not Ready to Accept

Just four days after King’s assassination in April 1968, Congressman John Conyers (D-MI) introduced legislation to establish a federal holiday in his honor.

Conyers understood King’s importance not sentimentally, but structurally. He recognized that King represented a demand that constitutional promises be kept—in housing, employment, foreign policy, and economic life. Congress, however, was unwilling to legitimize either King’s contributions or his critiques.

Congress was not alone.

Polling from the period shows that a majority of white Americans viewed King unfavorably both before and after his assassination. Many bristled at his condemnation of the Vietnam War, his calls for redistributing wealth, and his insistence that racial injustice extended far beyond the South.

Resistance to a King holiday was ideological—a rejection of the kind of democracy King envisioned.

Building Pressure from the Ground Up

As Congress stalled, the movement for a King holiday shifted to the states and cities. Throughout the 1970s, local governments began recognizing King’s birthday, often in limited or symbolic form. A patchwork of observances emerged—unpaid holidays, ceremonial proclamations, or commemorations folded into existing calendars.

These efforts were more than symbolic. They sustained momentum for a federal holiday during a decade when congressional action remained elusive. Black elected officials, labor unions, churches, and civil rights organizations kept the campaign alive, framing the holiday as a moral demand rather than a retrospective tribute.

Strategy and the Making of a Palatable King

Coretta Scott King played a central role in shaping the campaign for a King holiday, not simply as a steward of his memory, but as a strategist navigating a nation deeply resistant to her husband’s ideas.

From the late 1960s onward, she framed the holiday as a way to keep King’s work alive rather than to seal it safely in the past. The founding of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change reflected that vision. King’s legacy, as she understood it, was meant to remain politically active—rooted in nonviolent struggle and democratic accountability.

At the same time, she made a clear-eyed calculation. She recognized that white America would not embrace the King who condemned capitalism, opposed the Vietnam War, and demanded structural change.

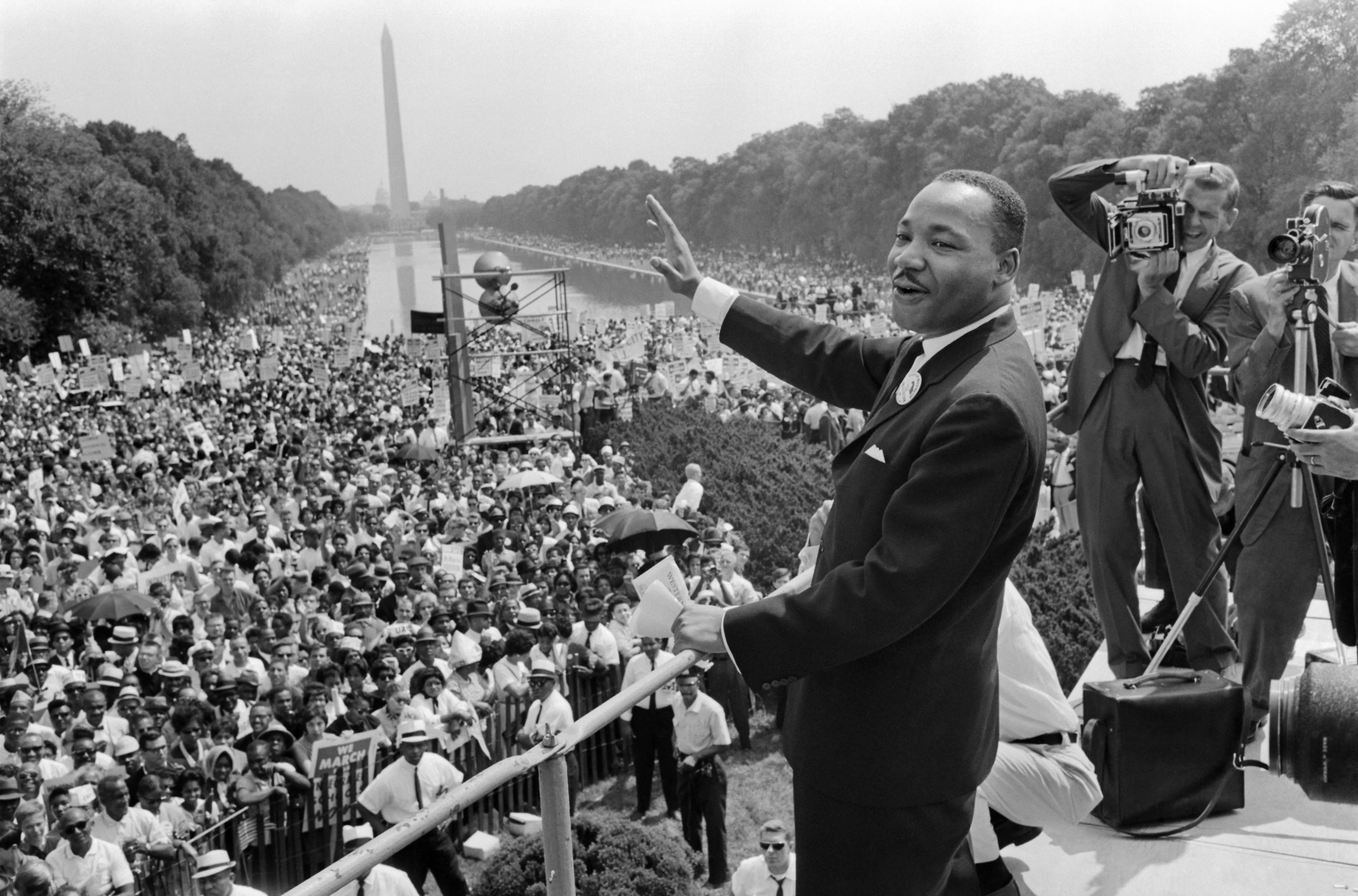

The version of King most likely to secure a federal holiday was the one the nation already felt comfortable claiming: the dreamer at the Lincoln Memorial, speaking of racial harmony.

This was not capitulation, but pragmatism. The consequences, however, were profound.

Over time, King was flattened, decontextualized, and frozen in 1963, severed from the criticisms of capitalism, racism, and militarism that defined his final years. What began as a strategy to make the holiday possible, morphed into how the nation came to mark it—emphasizing sentiment while sidelining King’s critique of American power.

A Turning Point in Culture and Politics

The early 1980s marked a decisive shift.

In 1980, musician Stevie Wonder released “Happy Birthday,” transforming a legislative campaign into a mass cultural movement. The song’s popularity made opposition visible and politically costly.

A massive march on Washington in 1981, led by Coretta Scott King, rendered years of grassroots organizing undeniable. Millions of petition signatures and sustained public pressure forced Congress to revisit an issue it avoided for more than a decade. By 1983, resistance to the holiday could no longer plausibly be framed as neutral.

Reagan’s Dilemma

Congress passed the bill establishing Martin Luther King Jr. Day in October 1983, and President Ronald Reagan—who had previously opposed the holiday, arguing that it would be too costly—signed it into law on November 2.

Reagan’s fiscal argument was a pretext. As president, he had dramatically expanded defense spending and embraced deficit financing, showing little interest in budgetary restraint. What he feared instead was alienating the white southern voters he had drawn to his coalition by appealing to their resentment over desegregation.

By 1983, however, sustained public pressure had narrowed Reagan’s options. Signing the holiday bill was less an endorsement of King’s life and legacy than a concession to a new political reality—a move designed to avoid the optics of openly embracing hostility toward racial equality.

Recognition Without Acceptance

The first federal observance in 1986 did not end the struggle for nationwide recognition.

Several states continued to resist, rename, or dilute the holiday well into the 1990s. Some paired it with Confederate Memorial Day or Robert E. Lee’s birthday; others denied paid leave to state employees. It was not until 2000 that all fifty states formally recognized Martin Luther King Jr. Day.

The gap between recognition and acceptance revealed a central contradiction: Americans were willing to honor King symbolically while continuing to resist the substance of what he demanded.

Service, Sanitization, and Backlash

In 1994, Congress redesignated the holiday as a National Day of Service. The shift encouraged civic engagement and had real value. But it also accelerated a larger trend—transforming King into a safe symbol of moral uplift while marginalizing his criticism of capitalism, militarism, and systemic racism.

That narrowing has intensified in recent years, amid federal efforts to dismantle diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives, abandon civil rights enforcement, and restrict how race and racism are taught.

President Donald Trump’s decision to eliminate free access to national parks on MLK Day—petty as it may seem—reflects a longstanding and deepening hostility toward what the holiday represents.

A Holiday Meant to Challenge

In 2026, on the fortieth anniversary of the first federal observance of Martin Luther King Jr. Day, the holiday remains what it has always been: a measure of the nation’s willingness to confront itself.

The resistance that delayed, diluted, and contested the holiday exposes enduring myths—that King was universally embraced and that racism ended with federal civil rights legislation. King was honored only after his critique was narrowed, and even then, only grudgingly.

The question the holiday continues to pose is not whether Americans will celebrate King, but whether they are prepared to reckon with what he demanded.

On that score, the struggle remains unfinished.