The Birth of Soviet Ukraine.

When the Russian Empire collapsed in 1917 during World War I, the lands of today’s Ukraine became a battleground of violence and instability until 1922. Multiple communities of former tsarist imperial subjects imagined the future in radically different ways.

Progressive Ukrainians wanted an independent Ukraine, socialists desired a future that was connected with the Russian Bolsheviks, but factions argued over degrees of autonomy.

Poles imagined a future that might include Kyiv and that certainly did not exclude Warsaw, peasants wanted land, and anarchists had their own ideas. The Bolsheviks inherited this cacophony and would spend the rest of the century trying to resolve these tensions.

The capital of the new Soviet Ukraine became Kharkiv, a former university and industrial city, where officials oversaw an experiment creating a polity both Soviet and Ukrainian, through korenizatsiia, or “indigenization,” a set of policies Union-wide promoting non-Russian nationalities. No one knew, however, what might be too Ukrainian, and therefore somehow threatening, or even what precisely “Ukrainian” included, in the Soviet context.

One arena these debates played out in was the arts.

In very few places in the entire early Soviet Union was there such an outburst of experimentation and creativity as there was in Soviet Ukraine, especially in Kharkiv. Inspired by encounters with Habsburg artists, or connections with Poland and Germany more than Russia, the experimental art of Kharkiv’s 1920s was unique.

Soviet Ukraine was also a center of Yiddish theater, had the only Polish theater in the entire Soviet Union, and funded the arts in German and Bulgarian, among other languages. Indeed, Soviet Ukraine was one of the most diverse places in the entire Union.

Soviet Ukraine was not only an artistic, but also an industrial center.

In addition to the mines of Donbas, Zaporizhzhia was home to DniproHES, the Dnipro Hydroelectric Station. Dnipro (then Dnipropetrovsk) became a center of rocket building in the 1950s and 1960s, and Mariupol (then Zhdanov) was a center for steel. Funding for industry in the Soviet period was extracted from the countryside, and Ukraine was its breadbasket.

To increase grain exports financing rapid industrialization, Stalin raised the grain quotas for newly collectivized villages. Combined with bad harvests this led to the Holodomor, the terror famine that peaked in 1932-33 when millions starved in Soviet Ukraine.

The legacy of this trauma is ongoing. Every November Ukrainians light candles in honor of victims of this famine. Today, in the midst of war, Russians are stealing grain from Ukraine (responsible for 10% of the world’s exports), mining fields, and setting grain silos on fire, weaponizing hunger once again.

Soviet Ukraine was one of the main theaters of World War II.

The borders of Soviet Ukraine changed in 1939, when Hitler and Stalin signed a non-aggression pact and the Soviet Union brutally occupied Eastern Poland, today’s Western Ukraine. Hitler broke that pact in June 1941 and the invasion brought devastation and the Holocaust, which fundamentally changed Soviet Ukraine.

Kyiv, for example, was 1/3 Jewish before the war, and over 33,000 Jews were murdered in two days at Babyn Iar. Yet all the small towns and villages throughout Ukraine witnessed Jewish death, in many cases with the involvement of their neighbors.

Just as during the years of war and revolution, many groups pursued their disparate goals with violence. The OUN, Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, and its (later) paramilitary group the UPA, Ukrainian Insurgent Army, desired independence for Ukraine, but in a narrowly-defined form. They fought for freedom from the Soviets—and the Nazis, once it was clear the Nazis did not support Ukrainian independence—but are also implicated in violence against their neighbors.

Violence between Poles and Ukrainians was fierce because of their incompatible national projects involving the same land. Survival for everyone in Ukraine meant negotiating with multiple partisan groups, occupying regimes, as well as the German and Soviet armies.

Soviet Ukrainians were everywhere: they served in the Soviet Army, and in the UPA, and as resistance fighters, and were murdered in the Holocaust because they were Jewish.

At the war’s end, Stalin kept those regions of eastern Poland he had occupied in 1939. Survivors who thought the city of Lwow would return to Poland were mistaken; it became Ukrainian Lviv. Poles were deported, and the few Jews remaining had to craft a new life.

Soviet Ukraine was a center of dissidence.

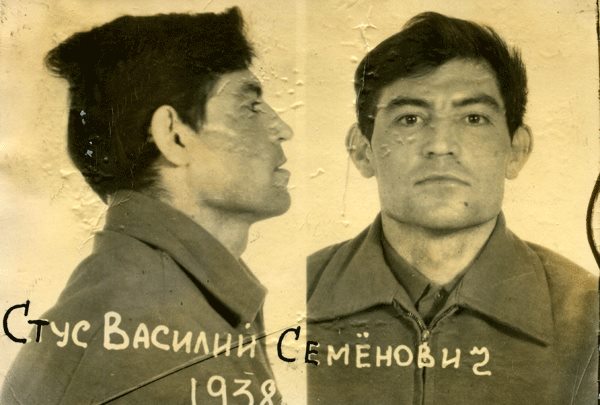

Poet Vasyl Stus, artist Alla Horska and the other 60’ers (shistdesiatnyky) were defiant towards the Soviet state and believed in the liberationist possibilities of Ukrainian culture. Stus served two terms in the gulag, and Horska was murdered by the KGB.

Yet Soviet Ukraine was also a center of nomenklatura elites—after all, Soviet leaders Nikita Khrushchev and Leonid Brezhnev came up through Ukraine. It was Khrushchev who made Crimea part of Soviet Ukraine in 1954.

And it was Ukraine opting for independence that was key to breaking the Soviet Union.

The Soviet Union, in short, was more than just “Russia.”

Wars, occupations, environment, demography, and history shaped the 20th century experience in Ukraine in particular ways.

Grappling with this Soviet past and disentangling the Ukrainian from the greater Soviet (and Russian) experience is an urgent challenge today, when Russia, the successor state, attempts to wipe Ukraine off the map.

Soviet Ukraine had its own story, and we should listen.![]()

Learn More:

Surveys:

Serhy Yekelchyk, Ukraine: What Everyone Needs to Know, 2nd edition (Oxford, 2020).

Serhy Plokhy, The Gates of Europe: A History of Ukraine (Basic Books, 2015).

For thinking about the Soviet past today, I suggest anything by Tetiana Zhurzhenko, for example:

Tetiana Zhurzhenko, “The Fifth Kharkiv,” New Eastern Europe, no. 3-4 (2015): 30-37.

For general reading:

Julia Alekseyeva, Soviet Daughter: A Graphic Revolution (note she uses “Soviet” but it’s about her Jewish family in Soviet Ukraine). This is a graphic novel that teaches well—and is a great introduction to Soviet history centered in Soviet Ukraine.

For non-textual sources:

Olesya Khromeychuk, producer, Nicola Roper, producer/director, “Ten Things Everyone Should Know About Ukraine,” Ukrainian Institute London, 2020. Great short films for Ukraine in general, but especially on topics related to the Soviet period. https://ukrainianinstitute.org.uk/10-things-everyone-should-know-about-ukraine/