When war between two generals and their forces over the future of Sudan erupted in April 2023, the world’s attention focused once again on Sudan and the dizzying array of militias, paramilitary organizations, and tribal forces involved. This month, historian Kim Searcy traces the roots of these fractious groups back to British colonial policies and the Arab supremacism promoted by Libya in the 1980s to remind us that the past casts a long, complicated shadow on Sudan.

The war between the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) and the paramilitary militia Rapid Support Forces (RSF) that erupted on April 15, 2023, has killed more than 800, injured 5,000, and displaced nearly a million people, according to United Nations sources. Relentless bombardment has destroyed the feeble infrastructure of Sudan’s capital city, Khartoum.

On one level, the war began because SAF leader General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and RSF commander General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, known as Hemeti, failed to reach an agreement on the future governance of Sudan and how to integrate the RSF and the SAF.

Tensions already simmering between the two sides came to a boil on April 13, when the SAF denounced the increased deployment of RSF troops in Khartoum and northern Sudan. Two days later the war between the two armies began.

In fact, the deep history of Sudan’s multiple, ever-changing militias has profoundly shaped the current war between two generals, producing instability that has reigned in the region for decades.

The History of Militias in the Sudan: The British

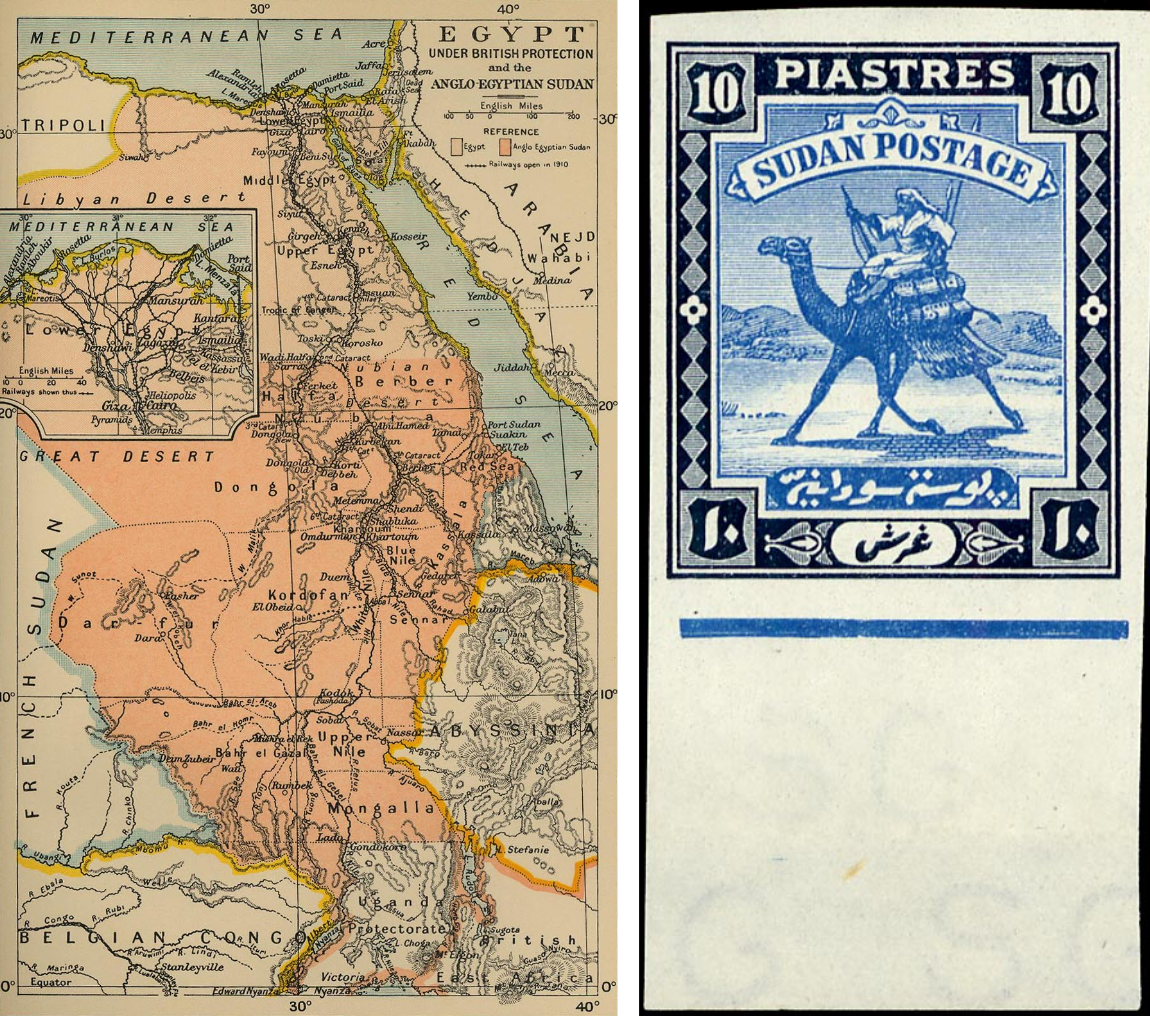

The roots of this conflict extend back to the colonial period of the Sudan known as the Anglo-Egyptian condominium (1898-1960). Even though the Sudan was under the joint control of Great Britain and Egypt, the latter had no real power. England dictated policies and effected governance in the Sudan during the period of the condominium.

Britain adopted a “divide and rule” strategy in which ethnic identities played a central role. A prominent feature of British colonial rule was its emphasis on Native Administration, a system of decentralized control in which the local population was segregated along tribal lines and ruled indirectly by local chiefs.

Native Administration empowered chiefs to rule over local populations and made access to land, resources, and government services dependent on one’s ethnic identity.

The British viewed Sudan as fundamentally Arab and non-Arabs as inferior. This view is explicit, for example, in the 1915 book Notes on Darfur 1915 by Sir Harold MacMichael, an intelligence officer for the colonial administration.

In 1917, Darfur, a largely non-Arab region, was absorbed into the Sudan condominium. British ethnic assumptions then shaped how this large colony developed. In stark contrast to the north of Sudan, by 1935 Darfur had only four schools, no maternity clinic, and no railways or major roads outside the largest towns. And Darfur has been treated as an unimportant backwater, a pawn in power games, by successive rulers ever since.

The British also sought to afford greater and more systematic representation to the main Arab groups as a way of controlling fractious tribes. Until this period, some of the large Arab tribes were decentralized and led by sheikhs, whose power was often limited to a camp or a village.

The first of a series of laws reorganizing the Native Administration was the Powers of Nomad Sheikhs Ordinance (1922), which granted judicial powers to nomad sheikhs within their tribes. Although no administrative powers were mentioned, this ordinance was clearly the start of a process to separate Arab and non-Arab communities, their leaders, and their justice systems.

If a given Native Administration setup proved too intricate for practical political control, the British sought to simplify it, introducing new hierarchical structures that generally were more pyramidal and thus easier to control.

In particular, they united territories seen as too small or disparate to be viable for rule and taxation. Primarily concerned with keeping the peace in Darfur, the British system also used indigenous militias to quash any rebellions.

When the British encountered resistance, armed or otherwise, they did away with recalcitrant individuals, promoting new leaders and establishing new dynasties. Predictably, in so doing, they also created internal power struggles, some of which continue to this day.

Libya and the Formation of Janjaweed, Precursor of the RSF

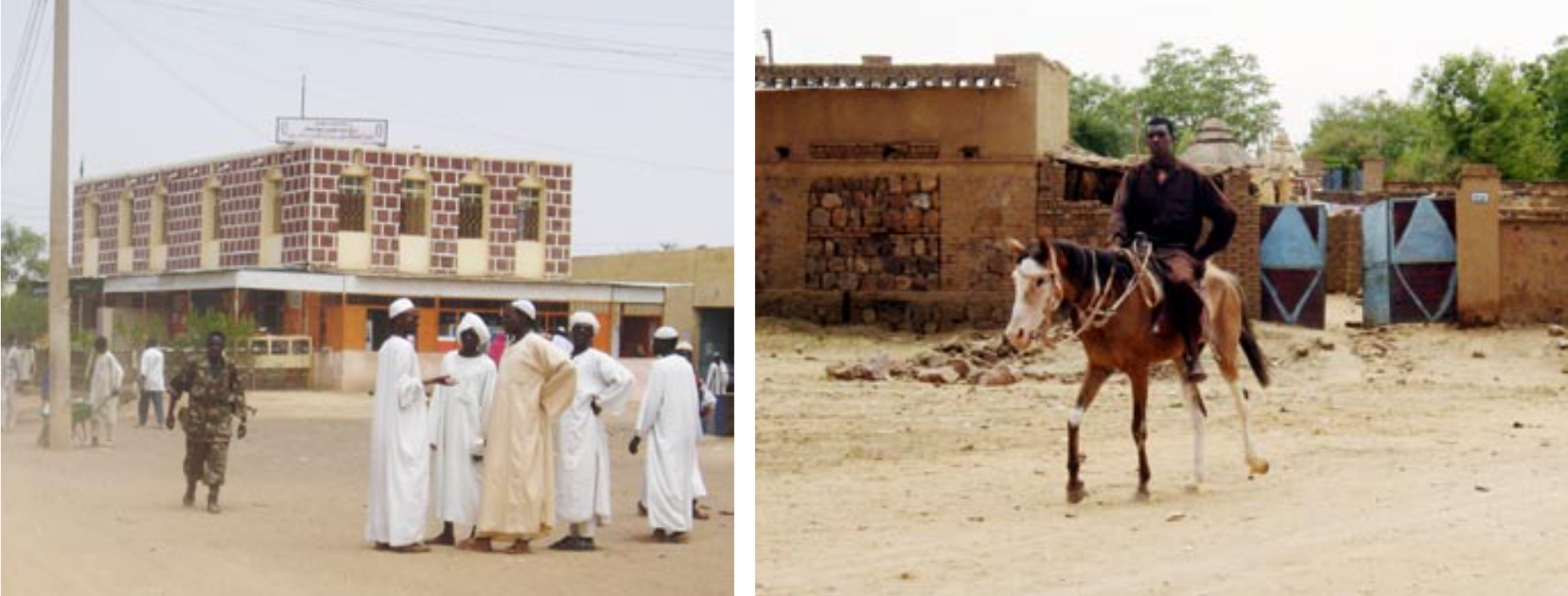

The practice of using tribal militias did not end when Sudan gained independence from Britain in 1956. In fact, the groups gained momentum in the 1980s and became linked with the government ideology of Arab supremacy. Libya played a major role in exporting this ideology and in flooding Sudan with weapons.

In the 1980s, Colonel Muammar Gaddafi conceived of an “Arab belt” across Sahelian Africa. In 1981, a Libyan-supported group called al-Tajammu’ al-Arabi (the Arab Alliance) distributed pamphlets in the region declaring that the zurga—a pejorative term for Black Africans—had been in control of Darfur long enough and it was time for the Arabs to seize the reins of power in the region.

In an attempt to control neighboring Chad, Libyan backed forces used Darfur as a rear base, provisioning themselves freely from the crops and cattle of local villagers. Many of the guns in the Darfur conflict came from those factions.

Gaddafi was ultimately defeated in 1988, but members of the forces he had armed, trained, and instilled with a virulent form of Arab supremacism did not vanish. They essentially morphed into what we now refer to as the Janjaweed. Gaddafi might have been gone from the scene, but violence inside Sudan continued.

The Arming of Arab Tribal Militias during Sadiq Al-Mahdi’s Time as Prime minister (1986-1989)

In 1986, Sadiq Al-Mahdi succeeded in forming a coalition government and became prime minister for the second time. Sudan seemed to be moving in the direction of democracy. There were political parties, independent trade unions, human rights organizations, independent newspapers, and tolerance for anti-government expression.

Mahdi himself campaigned on peaceful resolution of the civil war.

Immediately after his election, he met with John Garang, the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A) leader, and proposed a peace plan that included repeal of the Shari’a Laws implemented by his predecessor Jaafar an-Nimeiry (1969-1985), one of the main obstacles to peace.

To the disappointment of many, however, Mahdi suddenly backed down from his promises to disavow Shari’a Laws. The National Islamic Front (NIF) and its leader Dr. Hassan al-Turabi (Mahdi’s brother-in-law) had much to do with Mahdi’s change of mind.

Turabi was a staunch supporter of Shari’a Laws and the most hawkish in his quest for war in the South. Sadiq al-Mahdi’s resolve to institute some form of the Islamic penal code—despite its unpopularity with many northern and all southern Sudanese—became increasingly obvious.

Al-Mahdi not only failed to bring political settlement to the civil war, but exacerbated it by arming Muslim, Arabic-speaking tribal militias (the Missiriya, the Rizeigat, and the Ma’aliya, for instance) in Southern Kordofan and Southern Darfur provinces—especially in areas bordering SPLM/A’s strongholds—to fight the rebels. In these places, historic enmities persisted between Arabic-speaking settlers and southern tribes.

Armed with the latest weapons, the Arab militias carried out destructive activities against southern non-Arab communities. They burned villages, killed innocent civilians, raided cattle, and kidnapped young boys and girls to sell as slaves in the North. In most instances, these roving militias committed such atrocities with the full knowledge and support of the government army and local authorities.

The government’s supply of arms was not only confined to the Muslim Arabic speaking tribes; it has also armed rival southern tribes—for instance, the Murle, the Mandari, the Bari, and the Didinga—who viewed the SPLM/A as a threat.

The Al-Mahdi government continued the war with vigor, believing military force would bring the SPLM/A to its knees. The government had already characterized the North-South conflict as Arab versus non-Arab war to arouse the sentiment of the Arab World and gain material support for the war.

When the SPLM/A attacked Ad-Damazin, capital city of the Blue Nile Province, in 1988, Mahdi told the Arab world: “The Arab soil has been invaded from the South.”

Intra-Arab Conflicts

Since 2006, the largest single cause of violent death in Darfur has not been “ongoing genocide” of non-Arabs but fighting among Janjaweed collaborators. UNAMID officials say 80 to 90 percent of the violent deaths registered in South Darfur between 2006 and 2008 were occasioned by fighting among Arabs. (UNAMID is the African Union-United Nations Hybrid Operation in Darfur, inaugurated in 2007.)

After a significant drop in violent death across all Darfur in 2008, inter-Arab fighting erupted again on a large scale early in 2010, taking approximately 1,000 lives in the first nine months of the year. Arab informants say the figure is significantly higher, especially among the Abbala ethnic group, who seldom reveal their casualties.

Darfur’s Arabs can be separated into three main groups, with a caution that no generalization is absolute and the distinction between Abbala and Baggara communities is often blurred, especially in South Darfur, where they are both herders and farmers. Most of the Arab groups involved in contemporary militia activity are Abbala from North Darfur.

The heaviest and most recent fighting has pitted camel-herding Abbala pastoralists from the Northern Rizeigat group of tribes against cattle-herding Baggara associated with the Misseriya tribe. It has taken place on and around the fringes of the Jebel Marra region and is undergirded by some of the same racial stereotypes that fueled the counterinsurgency.

The focus of the fighting has been in the South Darfur state, the only one of Darfur’s three states where Arabs are in the majority. South Darfur is also the site of the most serious rebellion against the government by some of the Northern Rizeigat paramilitaries it armed in 2003—the followers of Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (Hemeti), of the Awlad Mansour branch of the Mahariya section of the Northern Rizeigat, who had been resident in South Darfur since the late 1980s.

Hemeti’s people—the landless Northern Rizeigat Abbala of North Darfur—were the backbone of the proxy forces armed by the government. Two decades after suffering major losses in the drought of the mid-1980s, the Northern Rizeigat became more deprived of services and more militarized than any other sector of Darfur society.

Like the insurgency in its early years, the killing of Arab by Arab has unfolded almost completely unremarked outside Sudan. Unlike the insurgency, the deaths are at least partially recorded, including by UNAMID, and well reported by some Sudanese journalists.

The protagonists and most of the victims are Arab pastoralists from tribes that supported the government’s counterinsurgency. They were offered loot, land, and sometimes salaries after years of marginalization during which their traditional rights of access to pasture and water were eroded, and the most basic services denied.

The fighting is, at one level, a struggle for the spoils of the counter-insurgency—use of, and access across, the land from which government-backed militias drove farming tribes perceived to be aligned with the armed movements.

Unaddressed in any serious, sustainable way, either by international mediators or by federal and state governments and institutions, it is an explosive blend of ethnic, political, and economic grievances, complicated by organized crime and livestock rustling.

Southern Sudanese Militias

Regardless of what government sits in Khartoum, the leadership has essentially maintained the policies of indirect rule imposed during the Anglo-Egyptian condominium. Sudanese governments have had a practice of arming and financing various militias, not solely the Janjaweed.

They have exploited simmering tensions between groups in order to quash rebellions or potential rebellions. For example, the government recruited from the Fertit for its militia called the Jaysh al-Salam (The Army of Peace) to fight the Dinka.

Fertit is an umbrella term used to denote the various non-Dinka, non-Arab, non-Luo, and non-Fur groups living in the Western Bahr al-Ghazzal. These groups are not related ethnically or linguistically and have a history of conflict with one another. Tensions between Fertit and Dinka in Western Bahr el-Ghazal grew after the independence of Sudan from the United Kingdom and Egypt in 1956.

Many Fertit believed that they were discriminated against by Dinka who increasingly dominated the administration of southern Sudan. These lingering hostilities grew worse after the Dinka-dominated Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA) launched an uprising against the Sudanese government in 1983, resulting in the Second Sudanese Civil War.

Few Fertit joined the SPLA, considering it a tool of “Dinka hegemony,” and in turn the SPLA considered the Fertit to be an ethnic group “hostile” to the rebellion. SPLA fighters launched a number of destructive raids on Fertit villages in 1985, mostly to acquire supplies to continue their guerrilla campaign.

A number of Fertit leaders consequently banded together to organize the “Army of Peace” militia as a self-defense force. It was supposed to defend Fertit communities from the SPLA but was also supposed to enact revenge on Dinka and Jur tribal communities that were blamed for the increasing violence.

Not all Fertit tribes supported the new militia, and some tribal leaders vehemently opposed the formation of the Army of Peace and the arming of civilians in general. Those tribal groups that did support the militia were mostly victims of SPLA raids on their villages.

The Sudanese government began to support the Fertit militia in 1986, while Captain Raphael Kitang, a retired army officer, became one of its most important commanders. The Army of Peace initially operated autonomously and exclusively in the surroundings of Wau, where it defended local villages from insurgents from 1986 to early 1987.

At a very early stage, however, the militia became notorious for many human rights violations such as the assassination of critical Fertit and Dinka tribal leaders as well as politicians, and most notably the indiscriminate killing and torture of Dinka civilians including children and pregnant women.

The Army of Peace’s Expansion of Operations with the Aid of SAF

The Army of Peace drastically expanded its operations after the arrival of SAF reinforcements in July 1987. These reinforcements included the infamous 242 Battalion (also known as the “Hun” or “Genghis Khan Battalion”) and were led by Maj-Gen Abu Gurun Abdullah Abu Gurun, nicknamed “Hitler” for his brutality.

Receiving better weaponry including tanks, the militia then began to act as auxiliary force to the SAF as new counterinsurgency operations were launched.

In August of that year, the group as well as the Sudanese army massacred hundreds of Dinka in the city of Wau, causing the local Dinka-dominated Wau Police and Wildlife Forces to take up arms to defend the civilian population.

The resulting intra-government fighting was extremely brutal and hundreds were killed. Dinka members of the police and Wildlife Forces formed death squads to retaliate against the militia, while the Army of Peace in return attacked the police headquarters with tanks.

Meanwhile the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) mostly evicted the Fertit militia from the rural areas around Wau. Only with Abu Gurun’s departure in November did the situation in Wau calm down.

With the support of the newly appointed county commissioner Lawrence Lual Lual, local Fertit community leaders managed to negotiate a peace agreement. Most of the militia subsequently demobilized in July 1988, though a faction remained active and continued to fight alongside the SAF and was integrated into the Popular Defence Forces (PDF) in December 1989.

The Popular Defence Forces (PDF)

The Popular Defence Forces was formed in 1989 through the Popular Defences Act, which defined the PDF as a “semi-military” force consisting of Sudanese civilians. The PDF was not a local militia, although it played a major role in arming and training the militias. It essentially was a reserve force of the SAF.

The Army of Peace continued to be active as part of the PDF until 1997, when it switched to the South Sudan Defense Forces (SSDF). The SSDF was created by the Sudanese government to unify the different South Sudanese pro-government militias into a single movement.

While serving with the SSDF, the Army of Peace continued to be officially led by El-Tom Al-Nour, who had risen to major-general in the SAF by 2006. The Army of Peace still enjoyed substantial support among the Fertit tribes during the last phase of the civil war, and continued to be most active around Wau, although it also had presence in other parts of Western Bahr el Ghazal.

Following the Juba Declaration of January 2006, which established the foundation for unifying rival military forces in South Sudan following the end of the Second Sudanese Civil War in January 2005, the SSDF began to disintegrate. The Army of Peace was fully integrated into the Sudanese Armed Forces and SPLA between 2005 and 2010, although there is evidence that the Army of Peace’s militia networks and militants were still active as late as 2018.

The RSF in Darfur and the 2023 Conflict

The Rapid Support Forces have emerged as the largest and most well-equipped of all the militias used in the Sudan since its independence. Its exact numbers are unknown, but estimates put it at around 100,000 members.

Created in mid-2013 to militarily defeat rebel armed groups throughout Sudan, the RSF is a Sudanese government force under the command of the National Intelligence and Security Services (NISS). It began as a tribal militia, but now includes fighters from various tribes and even from other countries such as Niger, Cameroon, Chad, Mali, Nigeria, and Libya.

The RSF led two counterinsurgency campaigns in the long-embattled region of Darfur in 2014 and 2015 in which its forces repeatedly attacked villages, burning and looting homes and beating, raping, and executing villagers.

The RSF, which evolved from the Janjaweed, received support in the air and on the ground from the SAF and other government-backed militia groups, including a variety of proxy militias.

In 2015, the group was granted the status of a regular force and, in 2017, the RSF was incorporated as a part of the armed services of the Sudan. The militia was not part of the army, but rather an auxiliary force. The primary purpose of the RSF at this time was to serve as protectors of Omar al-Bashir, Sudan’s erstwhile military dictator.

Essentially, the RSF—and Hemeti in particular—were supposed to protect al-Bashir from any coups directed at him from within the ranks of the army. Ironically, when mass protests broke out against al-Bashir’s rule in 2019, the army removed al-Bashir from power.

Hemeti did not protect his former patron, rather remarking at the time that the protestors’ demands were legitimate. Following al-Bashir’s removal from power an uneasy alliance existed between the RSF and SAF.

That alliance collapsed on April 15, 2023, with each leveling vitriolic criticism against the other. Al-Burhan has characterized the RSF as bandits and rebels intent on flagrant destruction. Whereas Hemeti has claimed that he is pro-democracy and that he and the RSF are fighting for the right of the Sudanese people to have a civilian-led democratic government.

The war on one level is a conflict between two generals for control of the resources of Sudan. However, on a much more nuanced level, the war is a culmination of the historical marginalization of Darfur and the long-term use and arming of multiple indigenous militias to quash resistance to government rule in the region.

Books:

A History of the Arabs in the Sudan: And Some Account of the People who Preceded them and of the Tribes Inhabiting Darfūr by H.A. MacMichael

Kingdoms of the Sudan by R.S. O’Fahey and J.L. Spaulding

Darfur and the British by R.S. O’Fahey

State and Society in Dar Fur by R.S. O’Fahey

Articles:

Tubiana, Jerome, Tanner, Victor and Abdul Jalil Musa Adam: “Traditional Authorities Peacemaking Role in Darfur.” Peaceworks, United States Institute of Peace.

De Waal, Alex “Counter-Insurgency on the Cheap.” The London Review of Books, vol. 26, No.15, Aug. 2004.

Kebede, Girma, Sudan: “The North-South Conflict in Historical Perspective.” Contributions in Black Studies, Vol. 15(1997)

Blocq, Daniel S. “The grassroots nature of counterinsurgent tribal militia formation: The case of the Fertit in Southern Sudan, 1985-1989” In David M. Anderson; Oystein H. Rolandsen (eds.). Politics and Violence in Eastern Africa. The Struggles of Emerging States. Abingdon-on-Thames, New York City: Routledge pp. 172-186.

Africa Watch (1990), “Denying the Honor of Living: Sudan a Human Rights Disaster.” New York City: Human Rights Report.

Wassara, Samson S. (2010). “Rebels, militias and governance in Sudan.” In Wafula Okumu: Augustine Ikelegbe (eds.) Militias, Rebels, Islamist Militants. Human Insecurity and State crisis in Africa. Pretoria Institute for Security Studies. Pp. 255-286.

Vuylsteke, Sarah (December 2018). “Identity and Self-Determination: The Fertit Opposition in South Sudan.” HSBA Briefing Paper. Geneva: Small Arms Survey

Flint, Julie (October 2010) “The Other War: Inter-Arab Conflict in Darfur.” HSBA Working Paper. Geneva: Small Arms Survey.