Those seeking better understanding of current events in Ukraine would do well to read The Last Empire, Serhii Plokhy’s new history of the demise of the Soviet Union. Ultimately, the decision by Ukraine to declare independence ensured that the Soviet Union had become an irrelevancy and its dissolution had become an inevitability. Although questions of ethnicity did not dominate the discussion at that moment, most political decisions were contingent on realities shaped by the Soviet Union’s ethnic patchwork.

The watershed event was the three-day coup in August 1991. Gorbachev was on vacation after the signing of the START Agreement with President George H.W. Bush in Moscow. The KGB cut the beach house from communications and surrounded it, leaving Gorbachev a prisoner. A cabal in Moscow declared a state of emergency. The coup’s catalyst was not the START Agreement, but rather a new union treaty that was to be signed after Gorbachev returned from his vacation.

Quickly, President Yeltsin signed a decree banning the Communist Party in Russia. Before the coup, Gorbachev was General Secretary of the Communist Party and thus leader of the USSR. After the decree it was unclear just what he was the president of. The demise of the party created a void to be filled by representatives of the Russian Republic.

Though never enacted, the union treaty’s contents became the catalyst in triangular relations between Russia, the Soviet Union, and Ukraine. The treaty was to have transferred sovereignty over the nation’s resources from the Soviet Union to the individual republics, also giving them the right to decide their own contributions to the Soviet budget and the right to consultation on foreign policies. It was this that the coup’s plotters feared.

In lieu of the treaty, Yeltsin’s Russians merely assumed rights ascribed in it. Gorbachev continued to fight for the treaty, but the Russians were too busy accruing functions from the Soviet Union to be bothered formalities. During the coup, General Lebed had advised Yeltsin that the Army would follow if he would declare himself commander-in-chief of the armed forces. This sort of logic governed events throughout the fall.

Meantime, the Speaker of the Ukrainian Parliament, Leonid Kravchuk, was under popular pressure from two sides. Ethnic Ukrainians in the west called for independence, while ethnic Russians in the east reacted vociferously against the Communist Party and “Moscow.” In Parliament, the Ukrainians introduced a declaration of independence that the Communist members were in no position to oppose. The measure passed the same day that Yeltsin had declared the Communist Party illegal in Russia. The issue of Ukrainian independence would ultimately be decided by a referendum on 1 December.

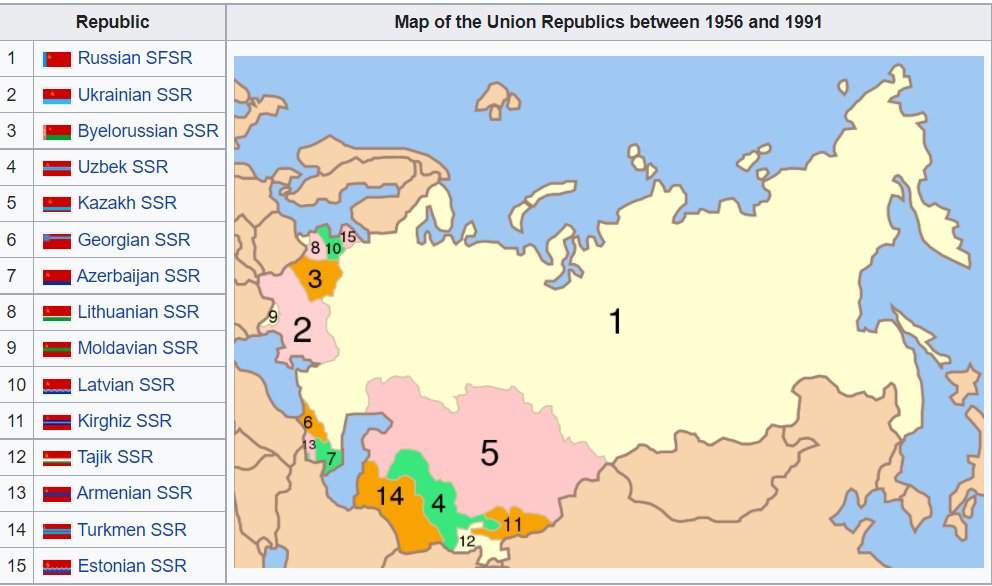

An interregnum followed between the Ukrainian declaration and referendum. Gorbachev’s union treaty became contingent on the results of the referendum. Russia saw a union without Ukraine as unacceptable because such a union would give more influence to the Islamic central Asian republics. During this interim, some suggested that ethnic unrest be fomented in Ukraine to forestall the referendum, among these Gorbachev himself and Leningrad mayor Anatoly Sobchak, who had among his protégés a KGB officer named Vladimir Putin. This did not happen. What did happen was a resounding vote in favor of independence. It received a majority in every oblast (administrative region), even in the ethnically Russian dominated east.

After the vote, Ukraine could not possibly participate in any union. Ukrainians were set upon moving forward independently, and retaining the union represented the past. The Russians also held this point of view. With Gorbachev out of the loop, the leaders of Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus determined to form the Commonwealth of Independent States, which was quickly adopted by eight other republics. This Belavesha Agreement also contained a stipulation that the Soviet Union no longer exist. With the republics already in control of the armed forces beforehand, there was nothing for Gorbachev to do but go away.

In addition to narrating these complicated events, Plokhy also describes the American reaction to them. Though it may come as something of a surprise to remember, President Bush and Secretary of State James Baker III were committed to maintaining the Soviet Union in order to maintain security over the Soviet nuclear arsenal and to avoid the sort of ethnic violence already seen in Yugoslavia: the disintegration of the Soviet Union was seen as a potential “Yugoslavia with nukes.” Plokhy also gives the impression, based on the memoirs and the documentary trail, that Bush and Baker were inclined toward a personal loyalty to Gorbachev. Defense Secretary Richard Cheney, on the other hand, was far more reckless, advocating immediate recognition of the independence of the republics.

However, with the 1992 election looming the White House had no choice but to cut bait when it became clear that events in the Soviet Union were not driven by policy set in Washington. This had been Gorbachev’s dilemma, too. Glasnost created a political climate that put Gorbachev’s base of support in Washington, not with a Soviet people rapidly inclined toward local nationalism.

What remained, like the British Empire, was a commonwealth. This is Plokhy’s most forceful and controversial argument. He resoundingly argues that, yes, the Soviet Union, like tsarist Russia, was an empire. This argument is potential dynamite in light of current events. Are the events in Ukraine a result of a nation divided neatly on ethnic and political lines, or is it an effort by a Russian Empire to strike back?